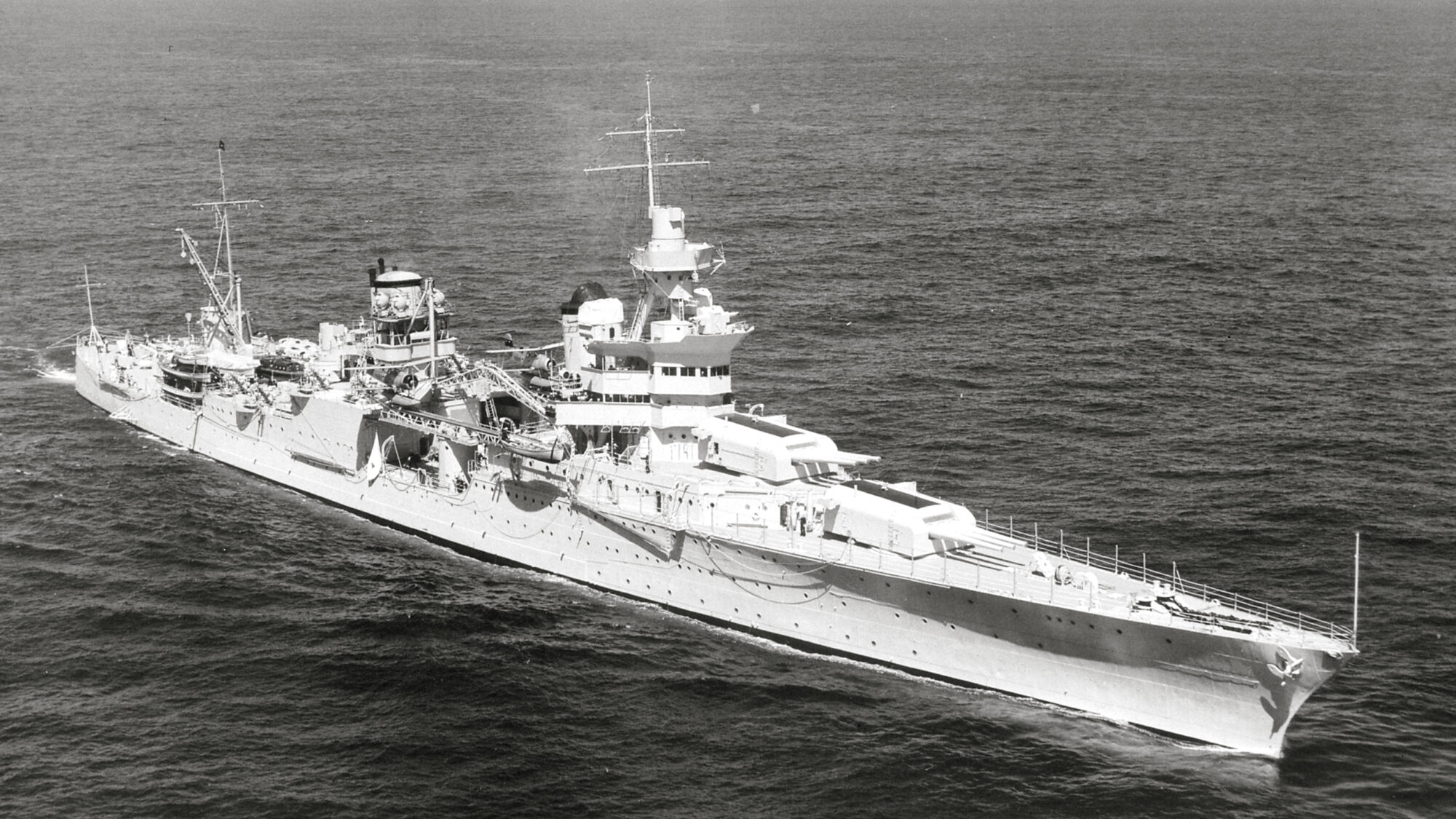

A few weeks ago, a surprising story was announced: the wreckage of the heavy cruiser USS Indianapolis, which was torpedoed and sunk by the Japanese submarine I-58 on July 30, 1945, had been located.

The long-lost wreck was discovered by a search team financed by multi-billionaire Paul Allen, the co-founder of Microsoft, in 18,000 feet of water at the bottom of the Philippine Sea.

Of course, many ships of all nations were sunk during the war, but several factors made this particular sinking—and the discovery of the wreckage—so intriguing and significant.

First, of course, was the tragic loss of life. Only about 300 of the 1,196 crewmen on board went down with the ship; the other 900 jumped into the water, clinging to flotsam, life jackets, or lifeboats. These survivors were in for a horrific fight for their lives.

Those in the water quickly began suffering from a variety of ailments: saltwater poisoning, dehydration, extreme hunger, and exposure under a brutal sun. But the worst part was the unrelenting shark attacks.

No other American ships were in the vicinity, so it took a while for anyone to realize that the Indy was missing. It was not until four days later that a PV-1 Ventura patrol/bomber plane on routine patrol spotted the men and radioed for immediate assistance in rescuing them.

Only 317 sailors and Marines survived their ordeal. It was the greatest loss of life from a single sinking in U.S. Navy history.

Another fascinating aspect is that the Indy had just delivered to the island of Tinian components needed to complete the assembly of “Little Boy”—the atomic bomb that was dropped on Hiroshima, Japan—and was heading to Leyte to join Task Force 95. Had she been sunk on the way to Tinian, the end of the war might very well have been different.

The Indy’s captain, Charles Butler McVay III, survived the sinking and was court-martialed for the loss of his ship. Of the 350 U.S. Navy captains whose ships were sunk during the war (including six other heavy and three light cruisers), he was the only one to be tried and convicted.

Suffering from mental health problems no doubt connected to the frightful experience, the court-martial, and his wife’s recent death from cancer, McVay committed suicide in 1968. (He was posthumously exonerated by Congress and President Bill Clinton in October 2000.)

The ship’s wreckage was found in August of this year by a search team and deep-water research vessel from the Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C. Allen, a well-known philanthropist and World War II history buff, footed the expedition’s bills, which ran into the millions.

Several books have been written about the tragic fate of the Indy and, in 2016, a Hollywood film, USS Indianapolis: Men of Courage, starring Nicholas Cage, was released.

Although there are no plans to recover any artifacts or human remains (if any still exist), at least pinpointing the location of the wreckage solves another of World War II’s many mysteries and reminds today’s generation about the ongoing legacy of heroism displayed by so many seven decades ago.

—Flint Whitlock, Editor

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments