By Martin K.A. Morgan

Some 16 million Americans served during World War II, and tens of thousands of sons of the State of Louisiana served in every branch of the U.S. military. They fought in every theater of operations, but almost 5,000 of them did not return. They perished during bombing missions over Japan and Germany, were lost at sea in the mid-Atlantic and the Pacific, and were killed during ground combat operations in places with names such as Corregidor, El Guettar, Troina, Tarawa, and Cisterna.

Louisianans also lost their lives during the campaign to liberate France. This is the story of two who paid the ultimate price during the D-Day invasion on a little hilltop in the small Normandy village of Graignes.

Benton J. Broussard was born on October 16, 1922, to a Cajun family living in the small town of Church Point in Acadia Parish, Louisiana, not far from the city of Crowley. As a child, his native tongue was not English, but French—a common reality among the people of the Atchafalaya basin in those days. In fact, he did not begin to learn English formally until he was forced to do so in middle school. He joined the U.S. Army on May 13, 1941, at Jacksonville Army Airfield, Florida.

George S. Baragona was born in the city of Slidell in St. Tammany Parish on July 24, 1919. There he grew up and attended Slidell High School, where he played almost every sport offered. He was an able athlete in everything, but was a star of the basketball team. After graduation, he worked for a time but then eventually decided to enter the service even before Pearl Harbor. On May 30, 1941, he enlisted in the U.S. Army at the same place where Benton Broussard had just 18 days earlier.

Both Broussard and Baragona made a critical decision after they completed basic training: they chose to join the parachute infantry. Some men did it for the “jump pay”—the extra $50 paid to each paratrooper in recognition of the hazardous nature of the sky soldier’s duty. Some men did it for the esprit de corps associated with being in an elite unit, and others did it because they assumed that the airborne would place them in combat sooner than any other Army branch.

In early 1942, Broussard and Baragona both graduated from jump school at Fort Benning near Columbus, Georgia, after completing the four-week course and making five qualifying, static-line jumps. They were in the right place at the right time to receive assignments to the unit that would ultimately take them to Normandy: the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment.

The Army had created this new regiment in July 1942 and immediately began filling out its ranks with recently qualified personnel who were on hand at the time. Benton Broussard was assigned to Headquarters Company of the regiment’s third battalion, while George Baragona went to the regimental Service Company.

The 507th remained at Fort Benning through the end of 1942 and then transferred to Alliance Army Air Field in Box Butte County, Nebraska, to prepare to go to war in North Africa. But the war there came to a conclusion in May 1943 with the surrender of Axis forces in Tunisia, and the 507th no longer had a rendezvous with a desert war.

In December, the 507th crossed the country to New York and boarded a troopship bound for the United Kingdom. Once there, the unit trained briefly in Northern Ireland before moving to an encampment at Tollerton Hall near Grantham in Lincolnshire. The time in England was spent preparing the 507th for its role in the upcoming invasion of Normandy, and the training was intense.

By this time, the regiment had been assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division as a temporary replacement for another regiment—the 504th—that had been badly bloodied during the fighting in early 1944 at Anzio and Nettuno in Italy. With just over 2,000 physically fit, well-trained, disciplined men, and over a year’s worth of constant preparation, the 507th was ready for action.

On May 28, 1944, the 507th’s 2nd and 3rd Battalions were moved to and sequestered at the airfield at RAF Barkston Heath at Grantham, where they began the final preparations for Operation Overlord, the Normandy invasion.

Misdrop Over Carentan

The 175,000-man invasion force was locked and loaded and ready to go on June 4, with the attack to begin early on June 5, but a raging storm in the English Channel caused General Eisenhower to delay the operation for 24 hours. Finally, on the evening of Monday, June 5, Benton Broussard boarded C-47 #41-38699 belonging to the 53rd Troop Carrier Squadron, 61st Troop Carrier Group, for the flight to Normandy.

George Baragona was on a different aircraft from the same squadron that evening (C-47 #42-32919). The C-47 “Skytrains” took off and flew south as a part of Mission Boston, the code name given to the operation to move the 82nd Airborne Division to Normandy.

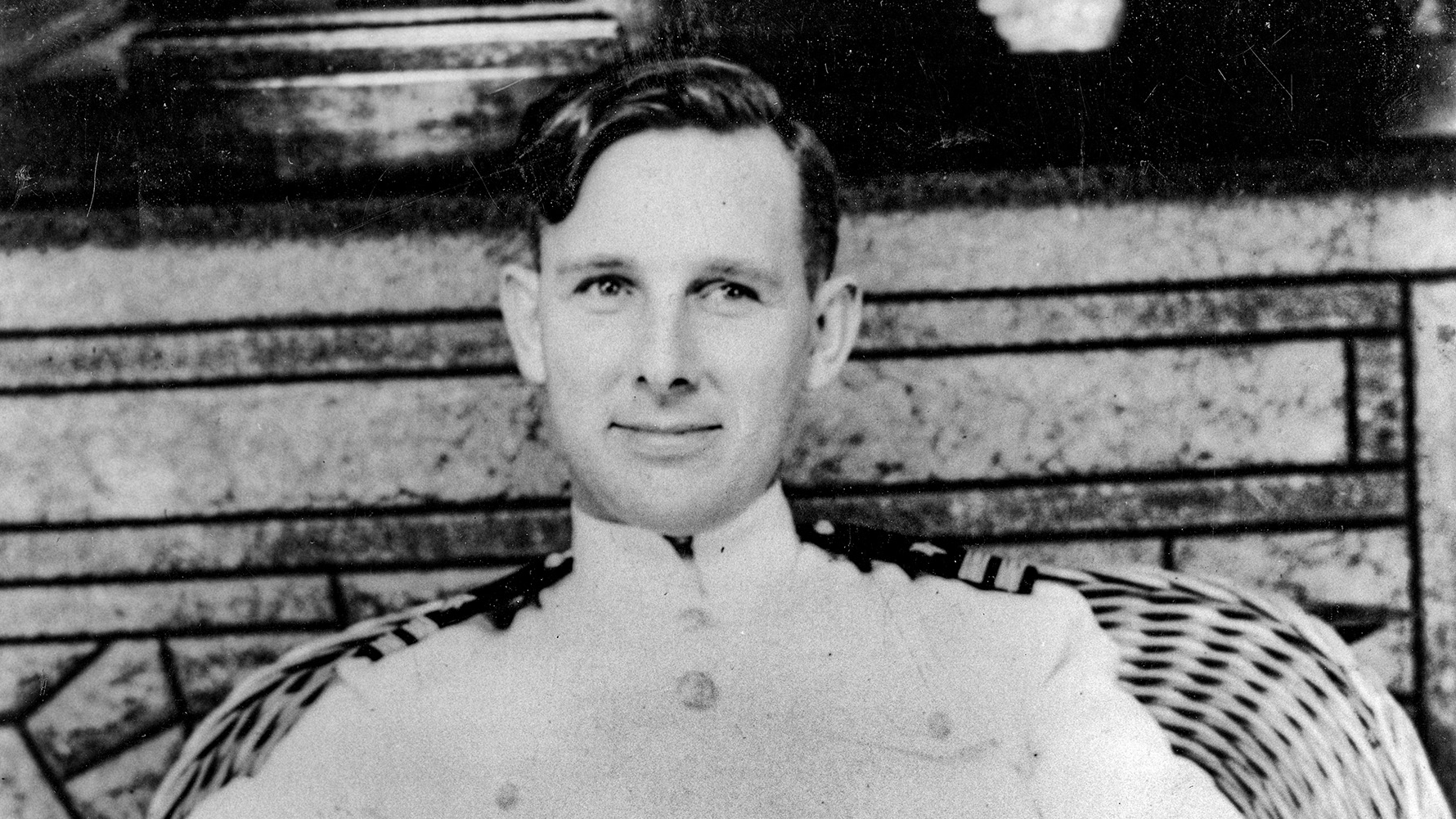

On another 53rd Troop Carrier Squadron C-47 in the same formation, the Operations, Plans, and Training Officer (S-3) for the 3rd Battalion, 507th PIR, Captain Leroy D. “Dave” Brummitt, was paying close attention to the trip across the English Channel. He later described the unexpected turn the journey took: “The Army Air Corps Troop Carrier Squadron carrying 3rd Battalion Headquarters and Headquarters Company followed the planned flight route from England until we reached the Normandy coast where we began to encounter German antiaircraft flak. Instead of holding course, the squadron took a different heading.”

Standing in the open door of his C-47 (#42-92066), Brummitt began scanning the dark terrain below and checking his wristwatch starting at approximately 2:30 am, Tuesday, June 6, 1944. He was surprised when the red light next to the door came on moments later because he could not identify any landmarks below. Despite the fact that he had spent many long hours studying maps and aerial photographs of Normandy, Brummitt could recognize nothing. The red light over the aircraft’s door indicated that he was to prepare the men to jump, but he nevertheless believed that the aircraft was not over its assigned drop zone. Despite this, he had the men stand up, hook up, and check their equipment.

Brummitt looked at his watch again and noted that the critical planned jump time had been reached, and yet the red light continued to glow. If they were indeed over the correct DZ, that light should have already changed from red to green.

“At that point I observed troopers in planes ahead of and around me leaving their planes,” he recalled. Knowing that the place for his “stick” of 18 paratroopers was with the rest of the company, Brummitt had to make a split-second decision, so he shouted the “Go!” command and jumped. Within seconds, only the flight crew remained aboard as C-47 #42-92066 flew away to the east, and Captain Brummitt drifted toward the ground beneath an open parachute canopy. George Baragona and Benton Broussard jumped from their two planes at approximately the same time.

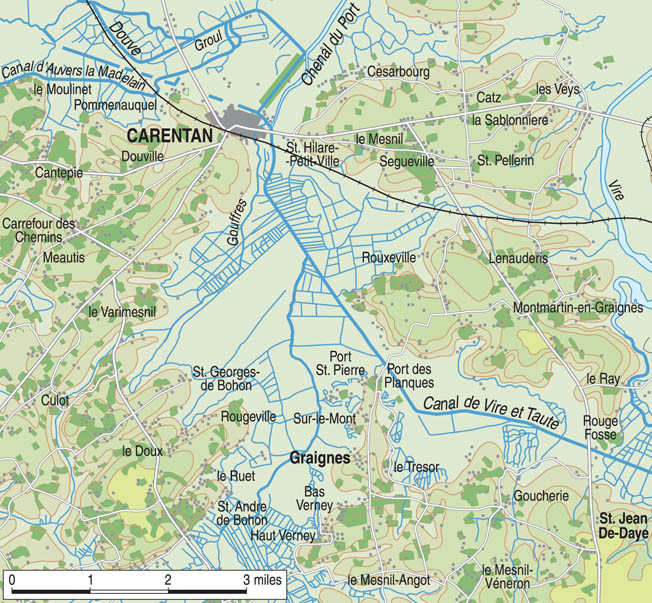

Although these three C-47s had been part of Serial 25, which consisted of 35 aircraft, they had strayed off course alongside six other Skytrains. Because of this slight miscalculation, nine troop carrier aircraft had just dropped almost 150 paratroopers of HQ Company, 3rd Battalion, 507th PIR, into the marshes south of the city of Carentan. They were supposed to have been dropped 15 miles to the north at Drop Zone “T” near Amfreville, but instead they had just been given the worst misdrop of any airborne unit on D-Day.

The Decision to Defend Graignes

At the time of the invasion, the seasonal flooding of the Vire and Taute Rivers had produced a broad area of inundation south of Carentan. This is where Broussard, Baragona, Brummitt, and nearly 150 others landed during the predawn hours of D-Day. At first light, they began slogging their way out of the marsh in small groups, moving toward a church they could see on a nearby hilltop, silhouetted by the rising sun. By 10 am, Captain Brummitt and 25 paratroopers had assembled in the village, which they soon learned was called Graignes. During the next two hours, more men climbed the hill and joined the group near the church.

As a precaution, Brummitt put out perimeter security to warn the rest in the event the enemy approached the village from the south, and then he made a reconnaissance of the area to the north. He was well aware that HQ Company’s mission required it to join the battalion with the greatest possible speed, “otherwise the ability of the 3rd Battalion to accomplish its mission would be drastically reduced to small-unit actions,” as he later described it.

During his recce, Brummitt observed no German forces between Graignes and Carentan, just 4.5 miles away across the saturated marsh of the swollen Taute River. By then he knew that the 82nd’s assembly area was just over the horizon to the north and, thus far, everything had been quiet. Considering these circumstances, the obvious thing to do, he thought, was move the herd toward Carentan.

“In my capacity as Battalion S-3, I formulated a tentative night-march plan to go through the flooded swamp area which we had waded, finding it to be waist to chest deep, or alternatively to go around the surrounding coast line to Carentan, link up with the U.S. force there, and continue on to the 82nd Division area,” he recalled.

But that plan was never to be because, shortly after noon on D-Day, Major Charles D. Johnston, executive officer of 3rd Battalion, 507th PIR, reached the hilltop. After discussing the situation with Brummitt, Johnston took control of the 507th men assembled in Graignes. To him, the idea of moving the force toward the American airborne units to the north was impractical because the 82nd and 101st Airborne Division drop zones were too far away. Major Johnston decided that the best course of action would be to keep the force in Graignes, organize a stronger defensive perimeter, and await a link-up with ground forces pushing inland from the landing beaches.

Mobilizing the Villagers

When the village’s acting mayor, Alphonse Voydie, learned that American paratroopers were assembling at the church, he rushed to the scene. By the time he arrived, Johnston had already begun the process of preparing defenses around the village. Johnston and Voydie then met to discuss the situation while Benton Broussard translated.

Without hesitating, Voydie and several other villagers told Johnston everything they could about the general layout of the area as well as the movement of nearby German troops. Because his men were going to need the ammunition and heavy weapons contained in the parachute equipment bundles that remained scattered throughout the marsh northwest of the village, Johnston asked the mayor about borrowing a boat to retrieve them.

On the spot, Mayor Voydie organized several teams of villagers to begin recovering the equipment bundles and hauling them back to the Graignes perimeter. They collected bundles that contained, among other things, five M1919A4 .30-caliber machine guns and two 81mm mortars—weapons that would make the positions around the village far more defensible.

The French also recovered large quantities of ammunition that they then delivered to the American defenders; Gustave Rigault was one of the citizens who assisted in this effort. From his farm at Le Port St. Pierre, a mile north of Graignes, Rigault could easily see collapsed parachutes dotting the marshy, flooded area that the French referred to as le marais.

With the assistance of his daughters Odette (19 years old) and Marthe (12), Rigault spent the afternoon of June 6 rowing out to and retrieving the U.S. equipment. While he concentrated on locating equipment bundles, the girls focused their efforts on recovering the white silk reserve parachutes that littered the area. What they hauled in from the marais was then deposited temporarily in a barn on the farm.

That evening, two paratroopers came to Le Port St. Pierre to retrieve it all, but they quickly determined that the quantity was far more than they could carry. Without hesitating, Odette limbered up the family horse and cart, which was then fully loaded with ammunition. She piled sacks of feed and fertilizer, as well as mounds of hay, on top to conceal the contraband cargo––a precaution in case she encountered a German patrol. Odette then personally drove the cart up the hill and into Major Johnston’s perimeter.

According to 1st Lt. Earcle “Pip” Reed, one of the 507th officers present in Graignes, the villagers hauled in “more ammunition than we thought we could ever use.” In addition to that, several field telephones, telephone wire, and a switchboard were delivered to the Americans on the hilltop.

Major Johnston also asked Mayor Voydie about the food situation. Since the mis-dropped troopers would almost certainly not be resupplied any time soon, he was genuinely concerned about how to feed everyone. Voydie wanted to help the paratroopers, but he realized that coming up with enough to feed more than 100 hungry men several times a day was not something that he could manage alone.

Recognizing that such an effort would require the cooperation and assistance of the entire community, he called a town meeting and appealed to the citizens of Graignes to place all the resources of the village at the disposal of the Americans.

The mayor must have been very convincing because there was a unanimous decision to help the paratroopers—a decision that was not entered into lightly as everyone in the village knew that the Germans would swiftly and harshly punish them for assisting the Americans.

Since the paratroopers would soon exhaust the supply of light rations they had carried with them to Normandy, something had to be done quickly. Voydie mobilized the women of the village in an effort to procure, prepare, and distribute food for the Americans. The proprietor of the village café, 50-year-old Madame Germaine Boursier, was recruited to organize an effort to provide the meals.

Dave Brummitt recalled that, when their rations ran out, Madame Boursier “set up a mess facility and procured foodstuffs, locally and from distant points, clandestinely transporting from the latter by cart and other concealed means.”

From that point forward, Madame Boursier set the standard for aiding her liberators. Under her direction, the women of Graignes began cooking on a round-the-clock basis so they could serve two hot meals each day. Using the café as her base of operations, she even coordinated and supervised the transportation of meals out to the soldiers occupying the many dispersed observation posts guarding the approaches to the village.

The Defenses at Graignes

With the civilians now fully mobilized, the American servicemen in the town had to adapt to an entirely new tactical situation than what they had been trained for. As Dave Brummitt recalled, Major Johnston’s decision to remain in Graignes “entailed an on-the-spot reorganization of our specialist personnel into provisional infantry fire teams reinforced by the machine gun and mortar platoons.”

But these were not infantrymen and this was not a rifle company. Although they had undergone “long and arduous unit training” before D-Day, that training had focused on supporting the 3rd Battalion’s mission, not on direct action with the enemy. Despite that, the men took to this new assignment as if they had trained for it all along. To Brummitt, they seemed “physically and mentally ready and eager to accomplish the missions assigned.”

At once, the Americans went to work preparing defensive positions and digging in along a main line of resistance just 250 meters south of the church. There, Brummitt organized a series of observation posts covering the open pastures and distributed his .30-caliber machine guns in such a way that their fields of fire interlocked with one another. The mortar platoon dug in both tubes just to the south of the church cemetery and positioned two men in the church belfry.

From that vantage point, the observers enjoyed an unobstructed view of the network of roads and trails leading to the village from all directions. Major Johnston established his command post in the Boys’ School next door to the church while the village’s defenses were being prepared. Men with rifles covered the main road leading uphill to the church, and a number of well-concealed antitank mines were laid to prevent vehicles from getting too close. In short order, rifles, machine guns, mines, and mortars were covering all routes into Graignes.

Throughout this digging-in process, men continued to walk into the perimeter. At approximately 5:30 pm on D-Day, more Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion, 507th personnel entered the village with 1st Lt. Elmer F. Farnham, 1st Lt. Lowell C. Maxwell, and the battalion’s communications officer, 1st Lt. Frank Naughton. Right behind them was a group of troopers from B Company, 501st PIR, 101st Airborne Division, led by Captain Loyal K. Bogart, who had injured his legs during the jump.

When he reported in at Graignes, Bogart insisted that he was still capable of helping, and asked for something to do. Major Johnston placed him in charge of the central switchboard at the command post in the Boys’ School. The remaining B Company/501st men were given a sector on the line to guard.

Two other 101st Airborne troopers, Pfc. Norwood H. Lester and Pfc. George A. Brown, also joined the group on D-Day, but they were not from the 501st. These two men belonged to B Battery of the 81st Airborne Anti-Aircraft/Anti-Tank Battalion; they had landed in the marsh shortly after 4 am on the 6th, but not by parachute. Lester and Green had been passengers on board Waco CG-4A #43-41826—a glider piloted that night by 2nd Lt. Irwin J. Morales and 2nd Lt. Lieutenant Thomas O. Ahmad of the 74th Troop Carrier Squadron/434th Troop Carrier Group.

Waco #43-41826 had been assigned the slot “Chalk 42” of Mission Chicago, the pre-dawn glider assault by elements of the 101st Airborne. “Chalk 42” was supposed to have landed 10 miles to the north on Landing Zone “W” near Hiesville alongside 51 other gliders, but instead it came down northwest of Graignes near a cluster of buildings known as La Brianderie.

Captain Brummitt placed Lieutenant Morales in charge of the right flank outpost of the line defending the hilltop, and Lieutenant Ahmad was given responsibility for a group of men near the church.

For three days, the scene at Graignes remained tense but quiet; unceasing noise from firefights, artillery duels, and naval and aerial bombardments, however, could be heard coming from the nearby countryside.

On June 9, a pair of soldiers from the 29th Infantry Division, who had been separated from their unit, walked into the perimeter, giving fleeting hope to the idea that forces advancing inland from the beaches would soon link up with the mixed group of Americans on the hilltop.

Other nationalities also became a part of the defensive force at Graignes. A pair of Spaniards who had escaped from a nearby German forced-labor camp emerged from the marsh and climbed the hill. Both men could speak French, so they made a great contribution as translators.

Then Flight Sergeant Stanley Kevin Black of the Royal Australian Air Force arrived. A bombardier in RAF No. 106 Squadron, Black’s Lancaster (#NE 150) had been badly damaged on a raid over Caen during the night of June 6/7. The bomber managed to limp approximately 20 miles to the northeast before finally crashing between the towns of Saint-Jean-de-Daye and Saint-Fromond. Black parachuted to safety that night, and was then taken by the French to Graignes because Allied troops were known to be there.

During the days that followed, the Allied troops in the village manned their outposts around the clock, adjusted the protective fires around the hilltop, and fine tuned the pre-sighted mortars. They established wire communications between the various dispersed positions around Graignes, prepared fallback positions, and generally made ready to contact the enemy.

Throughout these preparations, “the officers and men proved beyond a doubt that they were elite troops of the highest order,” as Captain Brummitt later described them. By June 9, the assembled group in the village numbered 182 (12 officers and 170 enlisted men). None of them had yet experienced combat with the enemy, but that would soon change.

“The Germans Are Coming!”

On June 10, elements of SS-Gruppenführer Werner Ostendorff’s 17th SS Panzer-Grenadier Division “Götz von Berlichingen” moved into the area around Graignes, setting the stage for battle. When the invasion began, the 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division was positioned more than 160 miles to the south near the city of Thouars in the Deux-Sèvres department of western France, but it quickly received orders to join the developing battle in Normandy.

To make the move, the division’s six battalions were divided into four Marschgruppe (“movement groups”) that made use of parallel axes of advance over the road network leading to the area around Carentan. SS Panzergrenadier Regiment 38 formed Marschgruppe 2; Graignes was directly in its path of advance.

On Saturday, June 10, a mechanized reconnaissance patrol from Marschgruppe 2 (16th Company, SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38) approached a section of the main defensive line that was under the command of 1st Lt. George C. Murn from B Company, 501st PIR, 101st Airborne Division. Murn’s men let the patrol get close and then opened fire, killing four of the enemy.

Simultaneously, another element of Marschgruppe 2 outflanked Graignes to the east by moving up the road running from Saint-Jean-De-Daye to Carentan. As they did so, another patrol was sent down the length of what is now the D89 to approach Graignes from the north using the bridge across the Vire-Taute Canal at Le Port des Planques.

There, a single 500-meter-long causeway permitted vehicular traffic to cross the inundated area north of the village, but it was being guarded by a detachment of 507th paratroopers under the command of 1st Lt. Frank Naughton. After a brief exchange of fire with the SS Panzergrenadiers, the Americans blew the bridge and pulled back to the hilltop.

That night, the outposts reported hearing activity south of Graignes and contact was made with probing German patrols several times. Knowing that a significant German force was out there in the hedgerows sent a wave of nervousness through the Americans, and the night was spent on full alert with officers conducting almost constant inspections of the perimeter.

Prior to that, the paratroopers at Graignes had been confident that American units to the north would get through to them before the enemy could launch any kind of serious attack against their perimeter. But the crescendo of enemy activity around the village on the 10th seemed to indicate that they could not expect relief to arrive in time. To the American paratroopers and the French civilians in Graignes, the moment of truth was close at hand.

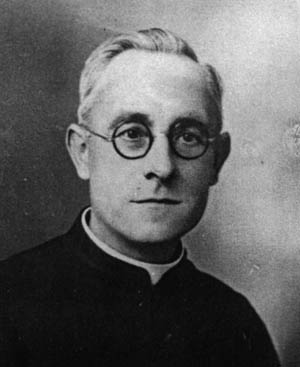

There was no sign of the enemy and all was quiet the next morning—June 11—the first Sunday since the invasion began. That being the case, Major Johnston gave permission for some of the men to attend Mass. Marthe and Odette Rigault went to Mass that morning as well, arriving just as the parish priest, 64-year-old Father Albert Leblastier, began the liturgy. Just 10 minutes later, gunfire interrupted the service.

Captain Brummitt heard firing south of the village, rushed to the scene, and quickly determined that a large German force was approaching Graignes. He shifted some of his men to reinforce the southern flank and prepared to receive the weight of a direct attack.

Back in the church, a woman burst into the sanctuary yelling, “The Germans are coming!” and causing a panic among the assembled parishioners and soldiers. During the brief gun battle, all of the villagers assembled for Mass sheltered inside the nave; the firing was over in less than 15 minutes.

A patrol element from SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38’s 1st Battalion had probed the village’s defensive line, causing the Americans to reveal some of their positions. As soon as the fight was over, Major Johnston ordered Brummitt to place all available personnel on the defensive line below the village. He correctly recognized that it had only been a probing action and that another, heavier, assault would soon follow.

At about 2 pm, the SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38’s 1st Battalion executed a light bombardment of Graignes. The fire came from either the infamous Model 34 80mm mortar (8cm Granatwerfer 34), a weapon organic to every German infantry company during World War II, or the Model 18 75mm light infantry howitzer (7.5 cm leichtes Infanteriegeschütz 18), a weapon that was definitely a part of SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38’s table of equipment.

The preparatory fire was quickly followed by a second infantry assault against the flanks of the southern defensive line. Although the attackers moved so swiftly that the perimeter was almost breached, Captain Brummitt immediately shifted forces to meet the threat, and the line held.

During this phase of the battle, the paratroopers unleashed supporting fire of their own through the effective use of their two M1 81mm mortars. With observers in the church tower providing fire direction, the Americans enjoyed a crucial advantage. The cumulative effect of the mortar fire, the crossfire of the machine guns, and accurate rifle fire disrupted the attack to such a degree that the Germans eventually broke it off.

First Casualties at Graignes

Although the line had held for a second time that day, the paratroopers and the citizens of Graignes began to suffer their first casualties. The church sanctuary soon became a busy place as the wounded were rushed there to receive medical attention from the 3/507th Battalion Medical Detachment, a portion of which flew and jumped with the Headquarters Company to provide direct medical support in the field. The detachment was under the command of 29-year-old Captain Abraham Sophian, Jr., and included several medics from the 507th and the 501st.

Father Leblastier and Father Louis Lebarbanchon, a 32-year-old former pupil temporarily in Graignes to recuperate from tuberculosis, provided comfort to the wounded soldiers as well as several injured villagers.

An uneasy quiet fell over Graignes following the second attack. During this lull, Captain Brummitt checked the line and found that mortar and small arms ammunition levels were beginning to run low. The remainder was then redistributed among the defenders to provide each position with an even supply.

While this was being done, an unnerving sound was heard rising from the maze of hedgerows to the south of the village. What was clearly the sound of heavy vehicular movement announced that the Germans were bringing up reinforcements. Major Johnston then had all of the civilians sent away since the observed evidence indicated that Graignes was about to be the target of a major attack.

The order to vacate the church came none too soon for Marthe and Odette Rigault, who after almost nine hours of confinement in the church during the day’s fighting, were “ready to leave.” Marthe remembered, “At 7 o’clock pm, Major Johnston told us that we should go home because they did not have enough ammunition for the night.” The two sisters then slipped out of the village and returned safely to Le Port St. Pierre.

From the hilltop the signs were growing more ominous with each passing hour. Through his binoculars, 1st Lt. “Pip” Reed could see two German artillery pieces being set up near a farm at Thieuville, a mile to the south of the church. SS Pzr. Rgt. 38 included several heavy weapons sections armed with several different types of guns that could have provided fire support for the battle.

First, 2nd Battalion, SS Artillerie Regiment 17 was armed with the Model 18 105mm light field howitzer (10.5cm leichte Feld Haubitze 18). Then there was SS Panzerjäger Abteilung 17, which was equipped with the potent and deadly Model 40 75mm antitank gun (7.5cm Panzer Abwehr Kanone 40). Finally, the 3rd Battalion, SS Artillerie Regiment 17 was armed with the most powerful weapon in the regiment: the Model 33 150mm heavy infantry gun (15cm schweres Infanterie Geschütz 33).

Although it remains unclear what type they were, at about 7 pm the two guns at Thieuville opened fire on Graignes, and incoming rounds quickly swept across the buildings clustered on top of the hill. As it began, “Pip” Reed looked up at the belfry just in time to see it take a direct hit. The enemy shell ripped through the observation post, killing 1st Lt. Farnham and another soldier.

The Final German Assault

The artillery barrage proved to be the beginning of the final assault against the Americans at Graignes. After a thorough “softening up” of the objective, troops from 1st Battalion, SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38 moved in for the coup de grace. To the defenders on the hilltop, it was immediately obvious that this assault force was significantly larger than the one from the afternoon battle.

With the observation post in the belfry destroyed, it was no longer possible for mortar fire to be delivered with any degree of accuracy. As the enemy crept closer, the mortar crewmen cranked the elevation of their tubes to the maximum in a desperate attempt to prevent being overrun, but it was of no use. The attacking SS panzergrenadiers closed ranks with the defensive perimeter in the village and, as darkness settled over Graignes, the Germans resumed their relentless drive toward the hilltop.

By the time the Germans made the final thrust into Graignes that night, the defensive perimeter south of the village had been reduced to a few isolated pockets of resistance. Defenders were running out of ammunition, and the enemy quickly exploited the situation by overrunning their positions. Those points of the line not overrun were cut off from communication with the command post and the aid station.

With that being the case, Major Johnston had Captain Brummitt pull his remaining outposts back to a defensive line closer to the village. As he attempted to make contact with each point along the line, Brummitt became involved in several intense firefights. When the enemy began to outflank the last position, the captain ordered the crew members of the remaining.30-caliber machine gun to withdraw to a previously designated fallback position. Just as the machine gunner and assistant machine gunner started to move, German rifle fire killed them both.

Without hesitating, Brummitt dropped his M1A1 carbine, scooped up the .30-caliber machine gun and its box of ammunition, but left behind the weapon’s M2 tripod because it had been damaged. He then leaped over a nearby stone wall that two other troopers were using for protection while providing covering fire. As he reached their side of the wall, German small arms fire killed both of the other two troopers. Brummitt swung the machine gun around, steadied it on top of the wall, and fired a burst in the direction of the enemy fire. After that, he “heard no more from that sector.”

When Brummitt returned to the hilltop area near the command post, Battalion Sgt. Maj. Robert Salewski informed him that Major Johnston had given the order to abandon the position and attempt to return individually to friendly lines.

At about that time, one final artillery concentration fell on the hilltop, this time targeting the Boys’ School. The shells battered the stone building, violently hurling fragments and rock in every direction. One of those rounds crashed into the roof directly above the room occupied by Captain Bogart and Major Johnston; when the round exploded, the walls collapsed in on both men. More fire landed on the building, killing some and sending others running for better cover.

Benton Broussard, who had been functioning as the major’s translator since the invasion began and had therefore been a part of the staff around the command post the entire six days, made a dash for the protection of the heavily damaged church. He only had to cover 200 feet to make it to the main entrance of the sanctuary, but he did not quite get there. One of the incoming artillery rounds caught him in the open and killed him just steps away from the church door.

Evacuating the Hilltop

Once darkness fell, it was clear that the paratroopers would not be able to hold on much longer. Captain Brummitt was informed that Major Johnston had been killed and, with that, command of what was left of the force at Graignes devolved to him. With the Germans swarming toward the center of the village, the American tactical situation in Graignes had fallen apart once and for all. Realizing that the enemy attack would most likely resume at dawn, and that their chances of survival would be slim beyond that point if they remained in the area, Captain Brummitt decided that the time had come to evacuate.

Still carrying the .30-caliber machine gun and ammunition can, he ordered Sergeant Salewski to round up everyone left on the hilltop. After assembling everyone that could be located, it appeared that they were the last remaining members of Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion, 507th in the village, so Brummitt led the entire group away toward the designated assembly area. The defenders had done everything in their power to hold out but, in the end, a numerically superior enemy attacking with supporting fire simply overwhelmed them. An entry in 17th SS Panzer Grenadier Division’s Kriegstagebuch (“war diary”) later ominously recorded this summary: “Graignes was taken at 11:30 pm on June 11th. The area was cleaned out during the course of the night of the 11th and 12th of June.”

Although Captain Brummitt was unaware of it at the time, a number of personnel did not depart the hilltop when he ordered the evacuation. Captain Sophian, his medics, and a group of wounded troopers were unintentionally left behind in the church. “Had I been aware of this situation, I would have made a specific move to bring them along,” Brummitt later said.

It remains unknown whether or not Captain Sophian received Major Johnson’s order to withdraw or if he possibly chose to remain behind with the expectation that his men and the wounded would be treated as prisoners of war. Those details do not matter much considering what happened next.

The Massacre at Graignes

At the end of the final assault the men of the 1st Battalion, SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38 stormed the church and found Captain Sophian’s aid station. They then forced the captain and all of the wounded outside where they were divided into two groups and marched away from the church. One group (nine troopers) was marched off to the south and the other group of five troopers was marched down to the edge of a shallow pond behind Madame Boursier’s café. At the edge of the pond, the Germans bayoneted the wounded men and dumped their bodies into the water.

The other group of 507th paratroopers was forced to march two miles to the south to a field near the village of Le Mesnil Angot. There, the nine men were shot and then buried in shallow graves.

When the 1st Battalion, SS Pz. Gren. Rgt. 38 took prisoners on the hilltop at the end of the battle, three of those prisoners were officers. Captain Sophian was captured unwounded in his aid station, and Captain Bogart and Major Johnston were pulled, wounded but still alive, from the rubble of the Boys’ School. All three were taken three miles to the southwest to the village of Tribehou, where they were interrogated for several hours and then executed. Their bodies were dumped along the Route de la Terrette (the present day D57). Major Johnston’s remains were not found until after the war.

But the execution of paratroopers was not the end of the atrocities that followed the conclusion of the battle at Graignes. Once in control of the hilltop, 17th SS troops proceeded to the rectory to exact punishment for aiding the Americans. They knew that the church’s belfry had been used throughout the battle as an observation post and they went looking for the people who had allowed it. When they found Father Leblastier and Father Lebarbanchon in their quarters, they dragged them into the courtyard and shot them both to death.

The Germans weren’t finished. They ordered any civilians still in the village to evacuate it. Two elderly women, Eugenie Dujardin and Madeleine Pezeril, both caretakers at the rectory, had planned to leave Graignes together in a horse-drawn cart but, as they departed the village on July 6, their old, sick horse died, stranding them. A German patrol, going through the village the following day, found the women and shot them both for failing to obey the evacuation notice.

Despite the violent battle, the brutal execution of U.S. prisoners, and the murder of the two French priests and the two women, more than 100 paratroopers made it out alive. Captain Brummitt’s group of troopers crossed the marais without incident that night and took up concealed positions in a hedgerow south of Carentan shortly before dawn on June 12.

Soon thereafter, another group being led by Captain Richard H. Chapman and Lieutenant Frank Naughton joined them, bringing the total number to 80 troopers from 3rd Battalion, 507th PIR, seven from B Company, 501st PIR, 101st Division, plus the two Spaniards and one French citizen. They reached the safety of U.S. lines the following morning.

Several smaller groups of paratroopers who became separated from the others in the pitch darkness ultimately found their way to Carentan during the days that followed, and some even remained hidden in Graignes to avoid capture. It is known that several paratroopers hid in the attic of the Girls’ School, and that one man even spent the next several weeks concealed in a large oven in an outbuilding on a farm known as Le Rotz.

This man, Pfc. Frank Juliano of B Company, 501st Parachute Infantry, remained in the oven by day and lived off of collected apples at night. (Although he did not starve, he did not eat like a king, either.) Juliano rejoined the 501st after ground troops finally reached the ruins of Graignes in late July.

The village’s citizens became refugees soon after the battle when the German military forced everyone to evacuate the area. They eventually returned in August only to find that their town was permanently touched by war.

Remembering the Sacrifices at Graignes

What happened to Graignes in 1944 is commemorated today with two street names: the main stretch of the D89 going through town is now known as Rue de 11 Juin 1944, and the road leading up the hill to the church memorial has been renamed Rue de 507e R.I.P. (Street of the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment).

Despite the atrocities committed in Graignes, no members of the 17th SS-Panzergrenadier Division ever faced justice. The U.S. Army conducted an investigation in 1947, but by then it was too late to find the perpetrators.

After the war, town leaders eventually chose to build a new place of worship at the bottom of the hill where D89 intersects with the D57. They also chose to convert the heavily damaged ruins of the old church into a memorial dedicated to the memory of those who lost their lives in the village in 1944.

At the heart of the memorial site, the final resting place of Father Leblastier and Father Lebarbanchon, is a crypt directly beneath the crossing inscribed with the word, “FUSILLES PAR LES ALLEMANDS LE 12 JUIN 1944” (“Shot by the Germans on June 12, 1944”). In the area where the church’s choir and the high altar used to be, a black granite plaque bears the names of the French civilians and U.S. paratroopers whose lives ended during the battle.

On that plaque’s center column, the names Benton Broussard and George Baragona are, coincidentally, one above the other. The Army recovered their bodies more than a month after the battle, and then interred them at the temporary American cemetery on the bluff above Omaha Beach at St.-Laurent-sur-Mer.

After the war, the families of both men were given the option of either having their remains permanently buried overseas, or having them returned to the United States. When both families chose repatriation, Broussard and Baragona were brought home to Louisiana. Today, Benton Broussard rests in Woodlawn Cemetery in the city of Crowley beneath a headstone that incorrectly lists him as having served in the 17th Airborne Division. (Although the 507th Parachute Infantry Regiment was part of the 17th Airborne Division later in the war, the regiment belonged to the 82nd Airborne Division when Benton Broussard served in it during the Normandy campaign. At the time of his death, he wore an 82nd Airborne Division patch on his left shoulder.)

George Baragona lies buried in his hometown of Slidell in Our Lady of Lourdes Cemetery beneath a custom headstone that incorrectly lists his date of death as June 6, 1944. In actuality, he survived D-Day and the five days that followed, only to be struck down by shell fragments during the same artillery bombardment that killed Benton Broussard.

Baragona’s headstone is decorated with a pair of airborne jump wings and the inscription “LEST WE FORGET.” These two sons of Louisiana, George Baragona and Benton Broussard, went to France in 1944 and left their lives on the hilltop at Graignes. They may not be household names, but they are not forgotten.

My great uncle James A Nebeling was killed there. I don’t know if he were one of the 501 medics assisting in the church and was murdered or did he meet his demise earlier? I saw his name on the new plaque at the church. Could you offer any information. Thank you

My uncle Nelson Hornbaker was a medic in 507th and murdered. Remains never found 6/11/44.

My great uncle, Harold Graham, jumped as part of 3HQ, 507th PIR on D-Day and was in the same C-47 as your uncle, 42-92773, with stick 25, chalk 47. I wish I had asked more questions as a kid of my grandmother and her siblings about Harold.

When this article talks about CPT Brummitt and his C-47 and the mis-drop, your uncle and my Great Uncle were in the plane beside him in formation.

My husband, also named George, is the only child of George Strickle Baragona. We visited Graignes in 1994, had dinner with Marthe and Odette, stayed at a bed and breakfast near the church ruins, saw the approximate site of the pond

where several soldiers were thrown, and attended a Catholic memorial service. This was a very emotional trip for my husband.