By Henrick O. Lunde

The second week in April 1940 was a stormy period in the North and Norwegian Seas. The weather deteriorated during April 7, with low cloud cover and fog. The wind increased to gale force on April 8 and reached hurricane strength in the Norwegian Sea, which had towering 50-foot waves. But another storm was about to break on the Norwegian coast. World War II was under way, and military forces, both Allied and Axis, were about to pounce on Norway.

Hitler’s Preemptive War on Norway

Allied plans to send military forces to aid the Finns against the Soviet Union were widely reported in the press in late 1939 and early 1940. The only way such aid could reach the Finns was through Norway and Sweden, and this would accomplish the main Allied objective of cutting off Germany from its source of iron ore, Sweden. The Germans might then be drawn into a hasty and risky operation in Scandinavia.

The Germans were well aware of Allied plans to interfere with their importation of iron ore and their landings in Norway and the Allied plans had not ended with the March 1940 peace agreement between Finland and the Soviet Union. Therefore, to frustrate Allied plans, secure the source of iron ore, extend the operational range of the German Navy, complicate Allied blockade measures, and prevent the threat that Allied bases in Norway would pose for German naval operations in the Baltic and North Seas, Hitler decided to carry out a preemptive strike.

Allied action started on April 8 with the mining of Norwegian territorial waters. The plan was to deny the Germans the use of those waters for importing iron ore through the port of Narvik, to provoke German counteraction that could lead to quick Allied victories, and to open a new theater of operations away from the front line in France. British troops were loaded on warships and transports for the occupation of various coastal cities in western and northern Norway.

The second week of April witnessed the largest concentration of naval forces in the North and Norwegian Seas since the Battle of Jutland a generation earlier. The British Home Fleet and all available naval units in northern Europe were at sea. These were reinforced by units from the French fleet. Practically every ship in the German Navy was involved in the attack on Norway. The only German naval units not at sea on April 9, 1940, were those undergoing repairs—three cruisers, six destroyers, and four torpedo boats. Eight German tankers and 45 transports carrying 18,276 troops were at sea or leaving northern German ports. A further 40,000 troops were ready for transport to Norway as shipping became available. The Luftwaffe was prepared to support the operation with more than 1,000 aircraft and the largest airlift operation (approximately 500 transports) up to that time in military history.

Thus, as the Allies were carrying out mining operations and readying their forces for action in Norway, nearly every ship in the German Navy was on its way to Norway with assault elements to capture Norway’s population centers. The success of the operation—which the German general staff considered “lunatic”— rested on three pillars: complete tactical surprise, the determination and professionalism of those involved, and mistakes by the enemy. Grand Admiral Erich Raeder, the commander in chief of the German Navy, told Hitler that the operation broke all rules of naval warfare but would succeed if the element of surprise were maintained. The Germans were prepared to lose at least half their navy in the enterprise.

Germany’s Invasion Force

The assault elements of the German invasion force were carried on warships divided into six task forces that were expected to land at the same time, 4:15 am on April 9, along the 1,000 miles of coastline from Oslo to Narvik. The German Task Force 5 (TF 5) had the mission of capturing the Norwegian capital, and it was hoped that the surprise operation would lead to the capture of the government, royal family, and the military commands. The Germans expected that this would lead to Norwegian capitulation and a peaceful occupation of the country.

The naval contingent of TF 5 consisted of the heavy cruisers Blücher and Lützow, the light cruiser Emden, three torpedo boats (small destroyers), eight R-boats (small minesweepers), and two auxiliaries (armed trawlers). Blücher was the newest of the major German surface units, launched on June 8, 1939, and commissioned on September 10, 1939. Its actual displacement was 18,200 tons although it was officially listed at 14,050 tons. Sea trials had just been completed prior to the Norwegian invasion. The Lützow was originally classified as a pocket battleship and named Deutschland. It was reclassified as a heavy cruiser on January 25, 1940, and given a new name. Hitler thought there would be undesirable psychological and propaganda consequences if a ship named Deutschland should be sunk.

The ships of TF 5 carried a combined crew of 3,800. Rear Admiral Oskar Kummetz commanded the naval component. The assault force of 2,000 men, commanded by Maj. Gen. Erwin Engelbrecht, consisted of two battalions of the 307th Infantry Regiment, one battalion of the 138th Mountain Regiment, plus artillery, engineer, and support units.

The capture of the Norwegian capital was a tall order for three infantry battalions. It was therefore planned that two airborne companies would seize Fornebu Airfield, a short distance southwest of the city. These companies would secure the airfield for the landing of two battalions and an engineer company from the 324th Infantry Regiment.

TF 5 left Swinemüde at 10 pm on April 7, and the major units (cruisers and torpedo boats) assembled in the Bay of Kiel at 2 am on April 8. The smaller and slower units had already departed with orders to link up with the rest of the task force at the entrance to Oslofjord during the night of April 8-9. The German ships sailed through the Great Belt, the main strait between the Danish islands, in full daylight on April 8. The progress of the group was followed closely by Danish observation posts and reported to the Danish Naval Ministry. The reports were passed to the intelligence section of the Norwegian naval staff throughout the day.

Light Norwegian Opposition

The Norwegians did not take immediate action to meet the threat since the consensus in the navy was that the German activities had nothing to do with an attack on Norway. Such an eventuality was ruled unrealistic in view of their estimation of German capabilities and overwhelming British superiority at sea.

TF 5 rounded the northern point of Denmark at 7 pm on April 8. It steered a westerly course while within sight of land in order not to give away its destination. The Germans changed course to the north after they were out of sight of land and headed for Oslofjord at high speed. Two British submarines, Triton and Sunfish, spotted the task force north of Denmark during the night. Triton made an unsuccessful attack on the German ships. The faster ships in the task force were joined by the slower vessels as they approached the entrance to the fjord.

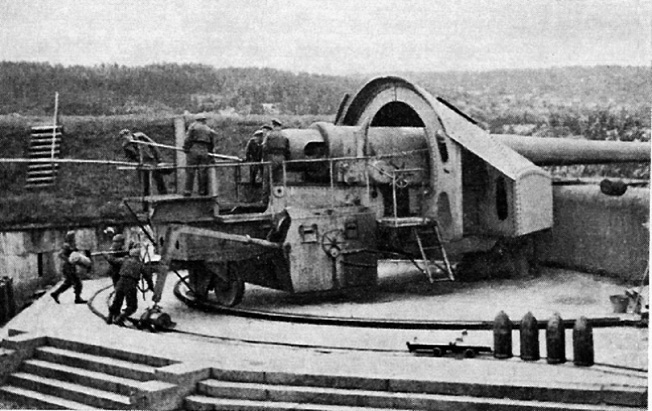

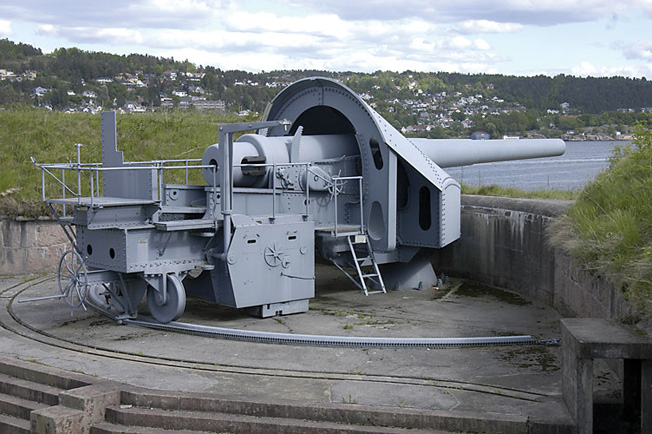

Two lines of forts at Oslofjord and Oscarborg protected the sea approach to Oslo. The Oslofjord forts had four battery positions, Bolærne, Rauøy, Måkerøy, and Håøy, on both sides of the fjord as well as a number of small ships. The Oscarborg fortress complex had batteries located on South and North Kaholm, two small islands in Drøbak Strait at the entrance to Oslo harbor. There was a main battery of three 280mm guns on South Kaholm and a torpedo battery of three 450mm torpedo tubes on North Kaholm. The three 280mm Krupp guns had been delivered in 1892. There had been an accident while they were under transport, and one barrel had fallen into the sea. It was immediately named Moses, and the other two were also given appropriate biblical names—Aaron and Joshua. A battery of 150mm guns and one of three 57mm guns were located on the mainland, on the east side of Drøbak Strait.

The antiaircraft protection for the forts consisted primarily of machine guns. The forts had only token infantry complements to protect against an overland attack. At full strength, the two fortress lines were to have 3,298 personnel, but only 957 were available at the time of the German attack. This left some batteries unmanned while others were critically undermanned.

The First Norwegian Casualty of World War II

There were four small patrol vessels in the outer part of Oslofjord in the evening of April 8. One of the vessels, Pol III, was the first to make contact with the German invasion force. Pol III was a small ship of only 214 tons, had a crew of 13, carried a single 76mm gun, and could manage a speed of only 11 knots. The Germans sighted Pol III, and the torpedo boat Albatros was ordered to take care of it. Albatros had a displacement of 924 tons, carried three 105mm guns, four 20mm guns, and six 210mm torpedo tubes. It had a crew of 122 and could reach a top speed of 33 knots.

The Norwegian patrol boat headed toward the German ships at full speed and fired a warning shot shortly before 11 pm. Albatros stopped, but the other ships proceeded toward Oslo. Pol III ended up ramming the German torpedo boat—apparently by accident—and tore a large hole in its side. The two vessels drifted apart, and at 11:15 the Norwegians fired three flares, the prearranged signal that foreign warships were entering the restricted area. After the Norwegians refused a demand to surrender, the Germans opened fire with machine guns and raked the Norwegian patrol boat. Although the German and Norwegian accounts differ, the Germans may have interpreted Norwegian activities to secure the deck gun as intention to open fire. The captain of the Norwegian vessel was mortally wounded and the first Norwegian to die in the conflict.

Passing the Norwegian Fortress Lines

The German task force had meanwhile continued on a northerly course and was closing in on the outer line of forts. The invaders were hoping to pass the forts without having to fire. The forts were prepared and the gun crews in place, but several fog banks rolled in and obscured the attackers. The German ships were visible to the battery on Rauøy for a short period and it managed to get off two warning shots and five live rounds before the ships disappeared into the fog. The Germans later related that the Norwegian rounds fell so far short that they were believed to be warning shots.

The German naval force stopped after passing the first fortress line. The troops on Emden were transferred to eight minesweepers. Four were to land troops to capture two of the battery positions in the outer line of forts so that the route would be clear for the transports bringing in reinforcements. Two minesweepers, assisted by the torpedo boats Albatros and Kondor, set out to capture the Norwegian naval base at Horten. The remaining two minesweepers followed the main force to land troops to capture Oscarborg in case the German ships were unable to force their way past that fort. The passage through the Drøbak Strait and the attack on Horten were to take place at the same time, 4:15 am. The day was beginning to dawn as the German ships approached Oscarborg.

Colonel Birger Eriksen, the commander of Oscarborg, had been kept informed about events in Oslofjord. Fate sometimes places the right person at the right location in war. Colonel Eriksen had a reputation among his colleagues for being a little trigger happy. He did not know whether the approaching warships were German or British, but he decided that such details were of little consequence. He ignored a subordinate’s suggestion to seek advice from higher headquarters before opening fire. He also decided that there would be no warning shots. His decisions had a devastating effect on the approaching German task force and saved the Norwegian government and royal family from capture.

“Three Hurrahs for Our Ship, Our Führer, Our People, and Our Country”

The German ships approached the Drøbak Strait in a column formation at 12 knots. The flagship, Blücher, led the column, followed by the Lützow, Emden, the torpedo boat Möwe, and the minesweepers R18 and R19, in that order. The distances between ships were about 600 meters. The German ships were dark, and all lights at Oscarborg and along the fjord were extinguished.

Admiral Kummetz interpreted the silence from the fort as an indication that the Norwegians would allow the Germans to pass. The delay, however, was a deliberate action by Colonel Eriksen. He calculated that the old, slow-firing guns of the main battery, manned by partial crews with little training, would only have time to fire one shot each before the lead German ship passed the fort. Colonel Eriksen wanted to be sure that the ship was close enough to make it virtually certain that the shells would find their intended target.

Colonel Eriksen ordered the batteries to open fire when the range finder showed 1,800 meters. The time was 4:21. The two shells from the 280mm guns were direct hits. The batteries on the east side of the strait also opened fire on Blücher. Two 280mm, 13 150mm, and 30 57mm projectiles hit the heavy cruiser before it passed through the fields of fire. The results were devastating. The first 280mm shell hit the base of the bridge and blew part of that structure into the water. The second 280mm shell entered Blücher’s port side behind the funnel and exploded inside the ship, killing many soldiers on the middle deck.

The fire from the shore batteries also hit the airplane hangar on deck, loaded with three aircraft and barrels of fuel. A powerful explosion ignited the gasoline. The inferno spread rapidly and set off aerial bombs, ammunition, and hand grenades stowed in containers on deck. The second round from the main battery also destroyed Blücher’s rudder controls. The cruiser avoided striking the shore by reversing its engines.

While the German ships were at full battle stations, the operational directive required that they leave their main batteries in secured position—that is, the guns were pointing directly forward or aft. They hoped that the Norwegians would interpret this as a sign of peaceful intent. While the main gun orientations may have slowed the German response, they were quick to react with their secondary batteries. The German fire in the short but intense exchange that followed was inaccurate since the shoreline was dark and the only way to pick targets was by observing the flashes from the Norwegian guns. The shore batteries sustained no serious damage.

It was too late for Kummetz to take his flagship out of the danger zone. The Germans tried to increase speed in order to get out of the reach of the Norwegian guns as quickly as possible, but this proved impossible since the ship’s engines were partially out of action. The burning cruiser presented an eerie sight as it slowly passed the batteries on the eastern side of the strait. The gun crews on shore could hear the cries of the wounded and dying aboard the ship. However, they reportedly also heard something else.

Crew members of the crippled ship were singing the German national anthem. However, this is not mentioned by Korvettenkapitän (Lt. Cmdr.) Kurt Zoepffel, Blücher’s adjutant. He relates that the assembled survivors, before abandoning ship, “joined in three hurrahs for our ship, our Führer, our people, and our country.” Whatever the case, the nationality of the attackers was now known.

“Torpedo the Ship”

As it moved slowly northward, Blücher came into the sector of the torpedo battery. The acting commander of the battery, Captain Andreas Anderssen, saw the burning ship approaching. He called Colonel Eriksen and asked if he should launch the torpedoes. Colonel Eriksen’s answer was short and left no room for misunderstanding, “Torpedo the ship.”

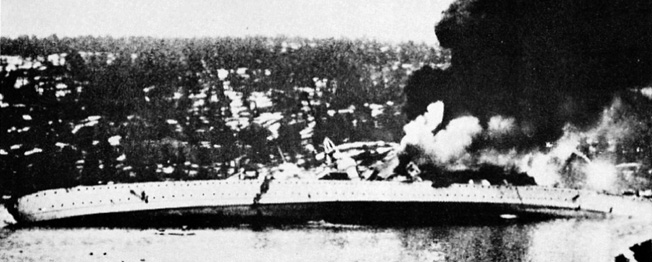

As he launched them against the German cruiser, Anderssen wondered if the 40-year-old torpedoes would function. The Germans did not see the wakes as the torpedoes hissed through the water. The first struck the Blücher forward, while the second struck amidships. Both torpedoes, but particularly the second, caused massive explosions inside the German warship. The engines were no longer functioning, and great amounts of water were streaming into the damaged ship. Captain Heinrich Woldag, Blücher’s skipper, ordered anchors dropped, and the great ship remained motionless with an 18-degree starboard list.

The Germans still hoped to save the ship by use of the auxiliary engines. The raging fire was their main problem. The ship’s torpedoes were fired to prevent their detonation. They exploded against the shore on both sides of the fjord. The 105mm magazine was located amidships and could not be flooded. The ship’s fate was sealed when this magazine exploded at 5:30 am, and the captain ordered the ship abandoned. The Germans had not displayed a flag while trying to force passage, but now the German battle flag was hoisted. The starboard list was increasing, and the great ship finally overturned and sank by the bow in deep waters at 6:22 am, with many personnel still on deck.

Oil spilled from Blücher covered the water and caught fire. The immediate area around the sunken vessel became an inferno. Scores of those who abandoned ship perished in the flames. Survivors came ashore on both sides of the strait, but mostly on the east side. Many were saved by Norwegian fishing vessels. Those who reached the shore were captured by Norwegian troops. Among them were Admiral Kummetz, General Engelbrecht, and Captain Woldag, who was seriously wounded and died within a few days at a Norwegian hospital. The loss of approximately 1,000 sailors and soldiers and one of the newest and most modern ships in the German Navy was a serious blow that disrupted the German timetable.

The Mistakes of Admiral Kummetz

After Blücher slowly passed outside their fields of fire, the Norwegian batteries shifted their guns to the next ship in the German column, Lützow. The cruiser also opened fire on the forts with its 150mm guns. Lützow received three direct hits from the Norwegian guns on the eastern side of the strait. The ship’s forward 280mm turret was put out of action. Captain August Thiele—Lützow’s captain—assumed that Blücher had struck mines in the narrows. This assumption and the fact that he was receiving heavy and accurate fire from the Norwegian guns caused him to conclude that the strait could not be forced successfully, and he decided to pull Lützow out of the danger zone before it was too late.

The other ships in the formation followed his example by reversing course and heading out of the fjord at high speed. The turning movement caused both Lützow and Emden to present their broadsides to the Norwegian batteries, which continued to fire. Several projectiles hit both ships. Thiele, while involved in this maneuver, received a signal from Admiral Kummetz directing him to assume command of TF 5. The German fire caused no casualties and very little physical damage to the Norwegian batteries.

Admiral Kummetz has been criticized for the tactics he employed in the attack. He undoubtedly felt pressured by his directive to land the troops in the capital around 5 am, but this alone fails to explain some of his actions. His decision to lead the column with his flagship is difficult to understand. It would have been more prudent to let the torpedo boat or minesweepers take the lead to test the Norwegian defenses, particularly in view of intelligence that there was an electrically controlled minefield in the waters off Drøbak. Admiral Kummetz’s after-action report fails to explain the slow speed used in the attempt to pass Oscarborg. It would have been wiser to pass the fort at high speed to reduce Norwegian reaction time and limit the time his ships were exposed. The loss of Blücher did not end Kummetz’s career. He was promoted to Generaladmiral (Admiral) and given command in the Baltic.

Colonel Eriksen Surrenders

Captain Thiele started preparations for a new attack on Oscarborg as soon as he had withdrawn what remained of TF 5 to safety. The Germans began landing troops on the east side of the fjord at 6 am, and within two hours about 850 German troops were ashore. General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst, the planner and overall commander during the German invasions of Norway and Denmark, was concerned by the delay in capturing Oslo. He issued a directive making the capture of the shore batteries at Drøbak the main objective. The Germans began advancing north toward Drøbak after capturing the nearby towns of Son and Moss.

Colonel Eriksen knew that the German withdrawal after their first attempt to pierce the fortress line was only a temporary pause. The bombing of the fortress by German aircraft started at 8 am and continued, except for a short period around midday, until 6 pm. The guns had no revetments, and the crews had to take cover in old tunnels that served as air raid shelters. The weak air defenses kept up a steady fire against the German aircraft, but the effects were minor. One Ju-52 transport plane was shot down and several sustained damage and had to make emergency landings. Lützow also participated in the bombardment.

The continuous air and naval bombardment caused few casualties at Oscarborg, but the material damage was substantial and the morale of the personnel deteriorated quickly since it was impossible to operate the exposed gun batteries while under constant aerial attack. The damage would have been more severe, but a large number of bombs failed to explode on impact.

The situation became untenable when German infantry captured the unprotected batteries on the eastern shore of the strait late in the afternoon. Colonel Eriksen could no longer prevent Germans ships from passing the fort. He decided that further resistance was hopeless and would only lead to unnecessary loss of lives. Negotiations leading to surrender began at 6:30 pm. The surrender took place at 9 pm on April 10, and TF 5 passed through the strait shortly thereafter. The surrender conditions were lenient. The enlisted personnel were to remain at the fort until conditions permitted demobilization. The officers were guaranteed their freedom and allowed to keep their personal weapons. The Norwegian flag flew over the fort alongside the German until April 21.

One Last Chance for Victory

General von Falkenhorst had received several situation reports on April 9, and with respect to the operations against Oslo all conveyed bad news. He learned that TF 5 was driven back in its first attempt to reach the Norwegian capital, the cruiser Blücher was sunk with great loss of life, the cruiser Lützow had sustained serious damage, and both the army and naval commanders were either killed or captured. The Horten naval base had not been captured, and the same was true for the forts controlling the approaches to Oslo. Finally, the Norwegians had rejected the German ultimatum and stated that they considered themselves at war with Germany.

The only chance left for the Germans to capture Oslo on April 9 rested with the airborne and air assault components of the operation. The Germans planned to capture Fornebu Airport by parachuting two airborne companies directly on the airfield. The plan called for these troops to seize the airfield quickly, allowing German transport aircraft to land two infantry battalions and an engineer company. It was a risky operation and would be the first use (along with the attack on Sola Airfield near Stavanger) of airborne troops to seize an enemy airfield hundreds of miles from their base.

The Norwegian force at Fornebu consisted of only three machine-gun positions and seven Gloster Gladiator fighters. Fornebu was not alerted until 4:30 am, more than five hours after the first contact with German warships in Oslofjord. The machine-gun positions were manned, and the fighter aircraft were prepared for takeoff.

There was a thick layer of fog over Oslo in the early hours of April 9. Breaks in the fog began to appear about 5 am, and five Gladiators took off to investigate the sound of aircraft overhead. As they broke through the fog, the pilots saw a number of aircraft of unknown nationality. The foreign aircraft disappeared in a southerly direction after the Norwegians opened fire. The slow-moving Gladiators could not match the speed of the foreign aircraft, and they returned to Fornebu.

Battle in the Skies Above Oslo

The German parachute operation was canceled when the aircraft carrying the paratroopers encountered heavy fog over the target area. The aircraft were directed to turn around and land at the airfield in Aalborg, Denmark, captured by the Germans earlier in the morning. The landing of transport aircraft at Fornebu was predicated upon the airfield being secured by German airborne troops. Since this had not taken place, orders were issued canceling the air operation after consulting headquarters.

It appeared that the Germans had suffered another serious setback. Then, one of those bizarre events occurred that often decides the outcome of a battle. This time the fortune of war favored the Germans. There are two versions of what happened. The official Norwegian naval history, based on General von Falkenhorst’s report, states that the cancelation order reached the first wave of aircraft but the following waves failed to receive it. Other sources relate a different story. Their version of what happened is that when the commander of one wave read the order to turn around he noted that it came from X Air Corps. He was subordinate to another command and therefore believed that the order was false or intended for someone else. He decided to ignore it and continue on to Fornebu.

The version given by Falkenhorst is more convincing. With all planes carrying the landing force airborne, it is obvious that the order to abort came via radio and its authenticity could easily be validated. All air elements in the invasion of Norway came under the operational control of X Air Corps, and each commander was no doubt fully aware of this fact. The operation was canceled because German paratroopers had not secured the airfield, and it would be strange for this not to be mentioned when the order to abort was given.

The Norwegian Gladiators returned to Fornebu to refuel, and all seven took off about 6:30 am. The pilots were not sure if Norway was at war, but as they climbed in a southerly direction they saw a dark cloud of smoke rise from the spot near Oscarborg where Blücher had sunk. Any lingering doubts were dispelled almost immediately as they saw a wave of 80 German aircraft heading in their direction. The Norwegian aircraft were at a greater height than the Germans, and Lieutenant Torbjørn Tradin, the squadron commander, gave the order to attack.

The Norwegian formation broke up as the squadron dived in among the German aircraft. The airspace over Oslo was filled with planes, and dogfights took place both above and below the cloud cover. One Norwegian aircraft was damaged and crash-landed at Fornebu. The rest of the Gladiators exhausted their ammunition and returned individually to Fornebu. Two managed to land before a radio message told them not to set down since the airfield was under attack. The remaining four aircraft landed on frozen lakes in the interior of the country. The Norwegian Gladiators acquitted themselves well, shooting down three Heinkel He-111 bombers and two Messerschmitt Me-110 twin-engine fighters.

A squadron of Me-110s that were to have protected and supported the German paratroops had not received the news that the airdrop was canceled. These aircraft were circling the airfield, and they destroyed the three Norwegian Gladiators that returned to Fornebu.

A Bold Landing

In the meantime, the first wave of Ju-52 transport aircraft arrived over the airfield. German fighter aircraft were circling, and fires were seen on the ground. The German commander interpreted what he saw as proof that the paratroopers had jumped and were involved in fighting on the ground. Therefore, he ordered his wave to land. The lead aircraft met heavy fire from Norwegian machine guns. The pilot gave full throttle, but before he was airborne again, the commander and several others were killed.

The transport planes began to circle the airfield, uncertain about what they should do. It looked like another part of the German plan to capture the Norwegian capital had failed. However, the fortunes of war took a favorable turn for the Germans. Plans called for the Me-110s to land at Fornebu to refuel after they had protected the landing of the paratroopers because they did not have sufficient fuel to return to Germany or Denmark. This is another example of the risks the Germans were willing to take in their operational planning.

The Me-110s had used up all their fuel waiting for the paratroopers, and the squadron commander decided to land his aircraft at Fornebu. He did not have much choice. When the transport aircraft saw the Messerschmitts land, they decided to do the same, and one by one the German planes landed despite heavy Norwegian fire. Two German aircraft were destroyed and five severely damaged. The number of Germans killed is unknown, but they were held at bay until the Norwegians ran out of ammunition and were forced to withdraw at 8:30 am. The Germans quickly took control of the airfield and signaled for subsequent waves to land. Six companies of Germans— about 900 men—were on the ground by noon.

The Fall of Oslo

The German air attaché arrived at the airport and briefed Colonel Helmuth Nickelmann, the landing force commander (commander of the 324th Infantry Regiment), on the situation in Oslo. As the companies were ready, they marched in close order formation toward Oslo.

There were about 1,000 uniformed Norwegian soldiers in Oslo that morning, but many were students at the various military schools. The 2nd Battalion, 5th Infantry Regiment in the Tradum training area 50 kilometers north of Oslo was the nearest sizable Norwegian combat force. The only organized formations in the city were a squadron of cavalry at the cavalry school and three companies of Royal Guards. One of the three companies had just demobilized and turned in its weapons and equipment at the Akershus Citadel. Maj. Gen. Hvinden-Haug, the Norwegian commander in the Oslo area, had dispatched one company of the Guards and the cavalry school squadron to capture the Blücher survivors, and this force could not be recalled since it had no radios.

The only available Guard company was quickly dispatched to stop the Germans at Fornebu from reaching Oslo. The Norwegian commander decided to use back roads on the way to the airport, and the Germans and Norwegians managed to pass each other without making contact. The demobilized Guard company tried to retrieve its weapons and equipment at Akershus, but the Germans arrived before the Guards could rearm themselves.

Colonel Nickelmann met the acting commandant in Oslo, Colonel H.P. Schnitler, at Akershus and demanded the city’s surrender. The two colonels had a conference with the city’s chief of police, and Colonel Schnitler telephoned the prime minister, Johan Nygaardsvold, now located in Hamar, and explained the situation. The Germans stated that they did not wish to become involved in the civil administration, promised not to occupy the royal palace, and would allow the Guards to continue their routine. Nygaardsvold gave Colonel Schnitler permission to surrender Oslo. The document surrendering the capital was signed at 2 pm.

The determined and decisive action of one individual—Colonel Eriksen—had upset the ambitious German timetable, and this delay enabled the Norwegian government and royal family to escape the capital before the Germans arrived. The military commands and the gold reserves of the central bank were also evacuated. Instead of the hoped-for quick coup to assure a peaceful occupation like that of Denmark, the Germans were forced to undertake a grueling 62-day campaign to subdue Norway in the longest campaign of the war prior to the attack on the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941.

I have enjoyed reading several of your articles.

Thank You, We visited Drobuk a few times, This is a very nice quiet town to hear then and now read this

account of the History of the occupation of Oslo the sinking of the German ship is amazing.