By William Hogan

By mid-December 1944, the 3rd Battalion, 33rd Armored Regiment, Third Armored Division “Spearhead” had seen plenty of action. Led by 28-year-old West Pointer Lieutenant Colonel Samuel Hogan, the 54 tanks and 400-plus men had participated in most of the major battles—often at the tip of the proverbial “Spearhead.” Its soldiers included tankers, infantrymen, mortar men, cooks, mechanics and often additions of engineers, artillerymen and antiaircraft cannoneers.

Theirs was a potent outfit, Task Force Hogan, named for its dashing commander.

After the breakout from Normandy and heavy losses at Mortain, the Task Force swung west and charged through France toward the closing of the Falaise Pocket. Sam Hogan led his columns in a Sherman tank, flying the flag of his home state of Texas from its radio antennae. To curious inquiries from liberated French nationals, Sam would respond: “That is the flag of the free Americans.”

“Ah,” said one elderly Frenchman who spoke a little English but informed the other onlookers, “That is the flag of the American resistance movement!”

Spearhead was ordered to thrust straight north into Belgium after the Falaise Gap was closed. This three-day running battle in early September 1944 was in fact a giant meeting engagement as Third Armored Division and their brothers of the 9th Infantry Division, the “Old Reliables,” set up a titanic ambush on a German corps retreating from the French coast back toward Germany.

From there, Task Force Hogan alternated taking the lead with its sister tank battalions within the “always out front” VII Corps. There were picturesque little Belgian villages liberated in a blur of heavy action followed by the joy of victory as grateful Belgians showered the disheveled tankers in kisses, flowers, and Champagne. From there it was into Germany proper. The tankers and infantry knew full well that the going would only get tougher.

The Allies plunged into the first defensive belt of the Siegfried Line only to outrun their supplies. The hard battles since the previous July took their toll on men and machines until the Spearhead division had less than 50 serviceable tanks, a quarter of the normal combat strength of 200.

Taken off the line to rest and refit, Hogan’s command settled in for a short period of maintenance. Patrols and probes of the German line portended a quiet winter until a renewed offensive could launch in the New Year, but Hitler’s “last gamble” offensive into the Ardennes rudely shattered any expectation of a quiet Christmas. The German objective was the Belgian port of Antwerp, lifeline of the Allies in Western Europe. Capture of the port would cripple supply lines and drive a wedge between Allied armies north and south.

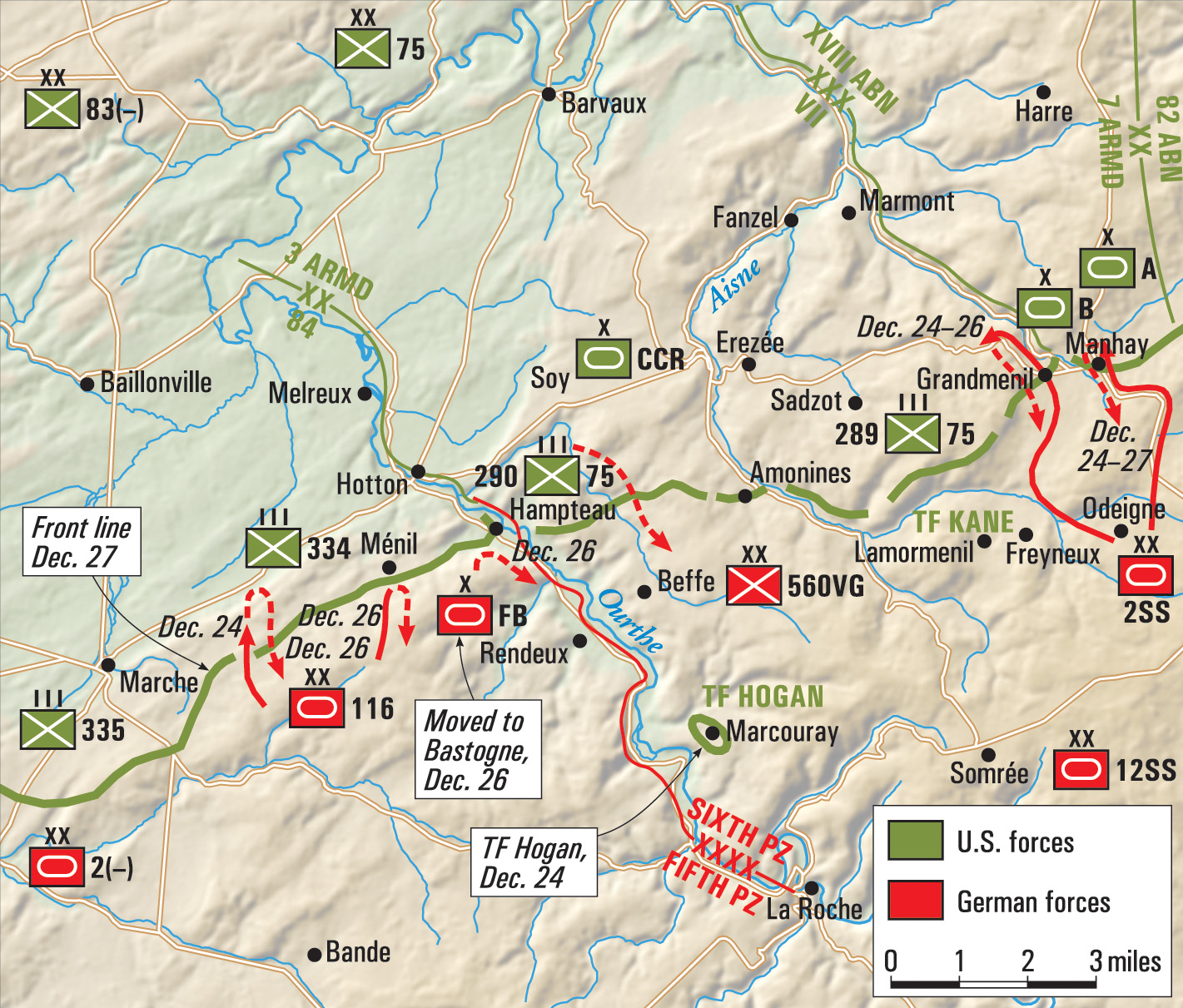

The German attack achieved complete surprise. Among the Allied leadership, there was shock and confusion. First Army commander Lieutenant General Courtney Hodges seemed overwhelmed and practically incapacitated. Still, his deputies at First Army headquarters in Spa immediately alerted and prepared to rush into the fray their two uncommitted units, the 82nd Airborne and Combat Command Reserve of the Third Armored Division. With 2/3 of its valuable armored combat power assigned elsewhere, Spearhead was notified to move out immediately, falling under XVIII Airborne Corps to establish a defensive line from Grandmenil to Melreux. As the only armored force in the northern shoulder of the Bulge, CCR was the only hope to slow down the German advance. The initial German “bulge” into the U.S. line cleaved General Bradley’s 12th Army Group from First Army, resulting in Eisenhower’s grudging decision to place First Army and thereby Third Armored Division under none other than Field Marshal Bernard Montgomery.

On the evening of the 19th, Task Force Hogan was put on a two-hour alert to move from the Stolberg Corridor to an assembly area in Hotton, Belgium. The understrength battalion was down to its Headquarters; George Company (with eight Sherman tanks, after losing seven in the Roer Offensive); A Company of the 83rd Reconnaissance Battalion, and Field Artillery and Anti-Aircraft sections (A battery from the 54th Field Artillery and a section from the 486th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion) to secure Houffalize, about 20 kilometers north of Bastogne.

Charlie and Service Companies would remain behind in the little resort town of Soy along with the regimental trains, the light tanks providing security for the Combat Command (Reserve) command post. The Task Force mortars were placed at Hotton, where they could support nearby units and help hold the town. The mortar platoon consisted of three M3 half-tracks, each mounting an 81mm mortar in the open bay of the vehicle and led by a Sergeant. The veteran of the group was Sergeant John “Little King” Grimes from tiny Forbes, Missouri. His soft face held narrow, piercing eyes that showed the kind of determination in a person that only adversity can bring. The other sergeants called him “Little King;” at 5’5”, he was short in stature but large in boldness and action.

As early as 15 December, rumors that German paratroopers were being prepared to jump into U.S. rear areas reached G2 (intelligence) channels. There were also rumors that German Commandos dressed as American military police were guiding columns into ambushes or in the wrong direction. To complicate matters even further, fuel resupply was late in arriving, so the U.S. task forces moved out with fuel tanks only half full.

The understrength column left Mausbach, Germany, and swung west in the direction of the little Belgian towns they had liberated the previous fall. Already the temperatures were freezing, and ice covered the roads as drivers squinted hard to see the blackout lights on the vehicle ahead. Drivers posted assistants outside the cab sitting on the fender to help steer. Most soldiers were fighting off chronic colds and coughs they had suffered since early November. The column moved toward the unknown at night, under cold, pewter skies streaked with the ominous glow of German V-1 flying bombs headed for Antwerp.

Sam didn’t need to say it, but the feeling was that sending 1/3 of a tank battalion, with half-filled fuel tanks, into what was already rumored to be a division-sized German counterattack was nothing more than laying down a “speed bump” to slow the enemy advance. He also knew that these were the hardest conditions to lead men; zero intelligence on enemy strength with unknown locations or intentions, plus bitter cold and lack of supplies, would test the officers, sergeants and soldiers to the maximum.

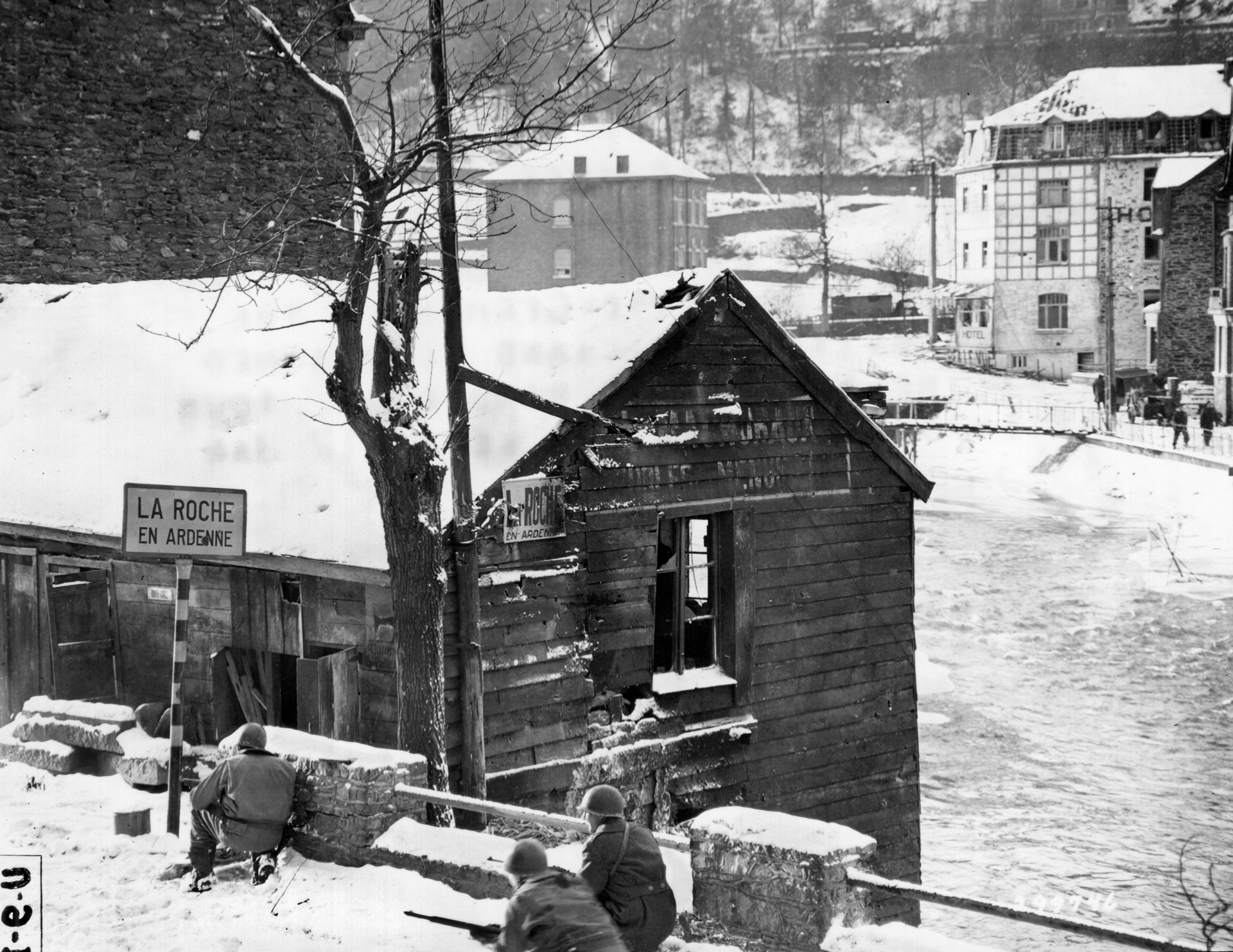

Eighteen miles due south, the 101st Airborne Division was rushing in to occupy Bastogne. Task Force Hogan moved in their direction, the River Ourthe covering the right flank and forming the boundary of the XVIII Airborne Corps. After 10 miles of nighttime movement, Hogan’s column arrived, bleary-eyed, at the village of La Roche without contacting any enemy. The center of town was littered with abandoned trailers left behind by supply units upon learning that the Germans were headed their way in strength. The 7th Armored Division trains (supply units) were still in town but eager to be relieved, as they were already receiving enemy fire from the outskirts of town.

Sam instructed his tankers and infantrymen to load up on the abandoned rations and cigarettes. He then detached his headquarters assault-gun platoon to assist the 7th Armored supply-and-services personnel in holding the town, which would keep his own supply route to the rear open. The gas tanks of Task Force Hogan’s vehicles were now half empty, and there was still no information coming through on the enemy’s disposition.

The cold night passed with the task force coiled up and on full alert. The sounds and flashes of artillery indicated the impending arrival of a wave of German armor. As the 20th dawned crisp and cold, Sam set out with his operations officer, Major Travis Brown, and his scout platoon leader, Lieutenant Clark Worrell, in two Jeeps to reconnoiter the forward line of troops. At the edge of town, a U.S. picket advised the passengers of the two Jeeps that the Germans ahead were rolling grenades down the hill. “Push on!” said Sam as he lit another Camel cigarette and cinched down his steel helmet. The Jeep drivers stepped on the gas, roaring down the road and kicking up gravel and icy mud.

Ten kilometers out of the town, they ran into a unit of American soldiers with their halftracks. These soldiers were eating rations while apparently guarding several fit-looking Germans in long trench coats and steel helmets. Something did not seem right. The Jeeps stopped, and the two groups stared at each other for a tense few seconds.

Suddenly, one of the “Americans” leveled his Tommy gun at Sam’s little party. “They’re all Germans, Colonel!” came the fearful yell from Jeep driver Private Charles Gast. The Jeeps emptied out in the woods as machine-gun bullets clipped the gravel behind Sam and his staff’s mud-encrusted boots. It was a very close call, as the “real” Americans escaped even as the German commandos stopped their pursuit to help themselves to the contents of the Spearhead Jeeps, including one of Sam’s prized Christmas fruitcakes.

Now separated from his battalion, Sam and his small party spent the next 24 hours fumbling through the woods. Twice they ran into enemy pickets, finally making it back to the friendly lines near a U.S. artillery battery, whose soldiers miraculously did not fire into the group of what they thought were Germans coming out of the woods. The lost patrol made its way back to Task Force Hogan’s new perimeter in the village of Marcouray. Sam learned that German infantry were trying to cut off his unit from the rest of the Third Armored Division. At approximately 1300 hours, Colonel Robert Howze of Combat Command Reserve ordered the task force to move to Amonines.

Strong German forces blocked the road ahead. Earlier, their roadblock outside the hamlet of Beffe had taken out a Sherman tank with Panzerfaust antitank rocket fire. The skirmish resulted in one American soldier killed in action—a forward observer from the artillery battalion—and 17 wounded. Flanking the position was impossible, as a cliff protected it on one side and thick woods crawling with Germans were on the other.

Marcouray was an ideal defensive position, with one flank protected by the Ourthe. Sturdy stone houses with fields of fire out to 1,000 yards dotted the village. Sam decided to stay put and block the advancing Germans. He reckoned it would take at least a regiment of Germans to drive his men out. Still, the task force hunkered down for an uneven fight.

Sam, a leader who infected his troops with his calm, confident demeanor, told them: “We’re on very defensible terrain, and we have a good deal of firepower and ammunition. This is where we’ll make our stand.” Little did they know they were to play a crucial part in pinning down an entire German panzer division, disrupting its advance toward Antwerp.

Task Force Hogan pickets improved their defensive positions through the night of the 22nd, engaging Germans on the other side of the Ourthe. Led by air-operations chief Captain Helaman “Ted” Cardon and Sergeant “Shorty” Wright of the recon platoon, observers lit up a dozen German trucks and Kubelwagens with artillery fire as they tried to bypass the American position. Clearing skies and moonlight allowed more fire missions targeting the German tanks attempting to bypass them. The horizon glowed with the light of burning enemy vehicles.

At first light, Sam stepped out of the stone farmhouse to the shocking sight of two German 8-wheeled armored scout cars loaded with troops screeching by his command post. He jumped back inside to radio the tank manning the roadblock in the direction the German scouting party was going. He then radioed the roadblock that the Germans had just passed. The tank crew had been alert and ready, but condensation overnight had frozen the turret ring hard and fast, and they were unable to traverse the turret to fire at the fast German scout cars. Normally very calm, Sam let out a few ice-melting expletives and returned to the task of dealing with “enemy in the wire.” The tank at the roadblock at the far end of the village blasted the second scout car, scattering its occupants into the woods.

Sergeant Wright and Captain Cardon took a patrol out and engaged the Germans, killing several. Another patrol found five enemy soldiers lying prone in a ditch near the road. Before anyone could stop him, a recon lieutenant fired his .45-caliber pistol at the backs of the heads of two. He was stopped and disarmed, and the remainder of the Germans became prisoners. Sam was livid. Besides one of his men acting in the precise way the enemy they were fighting acted—without humanity—now the task force was surrounded, in danger of being overrun, and had two German corpses with gunshot wounds to the backs of their heads. Things looked grim.

The situation was also deteriorating for the “unsurrounded” sections of Task Force Hogan, the headquarters assault-gun and mortar platoon, located 12 kilometers northwest of Sam’s position among the ridgetop hamlets of Hotton and Melreux. Staff Sergeant Arnold “Slack” Schlaich and Sergeant Grimes knew they were in trouble from monitoring the battalion radio net and from all the fire missions they had executed in the past 48 hours. After dawn on the 22nd, they fought off repeated probes by the forward enemy units that had already bypassed the Americans in Marcouray.

Looking out the window of a small stone building the mortars were using as their fire-direction center, Sergeant Grimes was shocked to see a Panther tank 300 meters away and moving toward Hotton. The tank was astride railroad tracks leading straight toward the little mortar section. “Kozloski! Svoboda! Get your gear! Enemy tanks coming up!” Unable to do much against an approaching tank with mortars, Grimes raised the alarm over the radio. Several intrepid souls of the 36th Infantry Regiment ambushed the lone Panther, taking it out with Bazooka fire from the rear.

Sergeant Grimes’ mortar section, Kozloski, Svoboda, and a third man named Debone, spent the entire night firing flares and alternating with high explosives when the little parachutes illuminated any enemy advance. Still, the Germans were able to slip past Hotton through an enfilade, skirting the town to cut off the assault-gun platoon in Melreux. They met stiff resistance from Schlaich’s lightly armored, snub-nosed howitzers shooting in direct-fire mode. The uneven duel went on into the 23rd, and as the Germans got closer Schlaich called in artillery and mortar fire, disrupting their attack. As the frigid evening grew near, the men in Melreux grimly prepared to destroy their assault guns, now close to empty of fuel and ammunition, and move by foot to rejoin their comrades in Hotton under the covering umbrella of their mortar fire.

Back in Marcouray, a German officer under a flag of truce arrived in a Kubelwagen, requesting to see the American commander. Blindfolded, the German lieutenant was led to Sam’s command post in the abandoned farmhouse. The battalion surgeon, Captain Louis Spigelman, a nice Jewish doctor from New York who completed medical training at the American University in Beirut, took time from caring for the 17 wounded troopers to help translate. With Doc Spigelman’s Yiddish and Sam’s broken German, they began the parlay. The German unlimbered a note signed by a colonel general demanding surrender. It boasted that Hogan was surrounded by three German panzer divisions and that “with a desire to avoid unnecessary bloodshed,” the Germans would accept the Americans’ surrender.

Sam lit a cigarette—partially to calm his nerves and to deceive the German that the Americans were well supplied. Taking a drag and thoughtfully letting it out, he replied, “We have orders to fight to the death, and as soldiers we will obey those orders.” Hogan added menacingly, “We’ve plenty of firepower and ammunition; if you want this town, you can try and take it.” The German officer, ramrod straight and shaking his head with disdain, returned to his lines.

The Americans settled in for a freezing Christmas surrounded on all sides. Cargo planes attempting to drop supplies by parachute met withering walls of antiaircraft fire protecting a German corps headquarters nearby. The despondent American ground troops saw white parachutes drift down into the woods, but from such low altitudes that a safe landing seemed improbable. Prayers were whispered from chapped, wind-burned lips that the flyers survived their falls and any would-be German executioners.

Two American fliers, bruised, battered but alive, walked into Sam’s perimeter bearing news that theirs was the last attempted supply drop. They had departed England hours earlier with only a vague idea of where to drop their canisters of fuel and medical supplies. An unfortunate mixup in the 435th Troop Carrier Group operations tent in Surrey had resulted in confusion of the town names of Marcouray and Marcourt, the few supplies landing within enemy lines at Marcourt, a Christmas present for the Germans. A last-ditch attempt to fire 105mm artillery shells loaded with medical supplies accurately delivered small canisters into the task force perimeter; however, the vials of plasma were all crushed.

On Christmas Eve 1944, in the worst winter to batter the Ardennes in over 100 years, with ammunition running low and all fuel exhausted, Task Force Hogan hatched a daring nighttime escape through the enemy encirclement. All day the starving, freezing soldiers prepared: tank engines ran without oil until they seized up, tires were slashed with bayonets or “dad’s old hunting knife,” and sugar was poured into fuel tanks. Noisy equipment was broken and abandoned.

Soldiers blackened their faces with cork ash or campfire soot, commando style. The freezing darkness creeping upon them was bittersweet to the American soldiers as they assembled in one long column of 400. Doc Spigelman volunteered to stay behind with the 17 soldiers too wounded to walk on their own. Sam and Doc knew what could happen to a Jewish officer captured by the Germans, but Spigelman refused to leave his wounded.

One last radio transmission came in before the radios were smashed to pieces at the end of a rifle butt: “A patrol from the 82nd Airborne will guide you into friendly lines, challenge and password are ‘Final’—‘Edition’—out.” Some Joe at headquarters had a grim sense of humor. Sam hoped the last words would not be prophetic.

It is tough to overstate how difficult it is to move 400 soldiers through wooded, snow-covered terrain at night in peacetime, much less through a gauntlet of German tanks and infantry. The Christmas march took the entire night. There were several close calls. The closest involved point man Sergeant Lee Porter of the battalion scouts, halting his silent slog through the frozen woods as he came upon the dark shadow of a German sentry blurting out a challenge. Before the German could react or call for help, the Missourian pounced on him, covering his mouth with his left hand while plunging his bayonet into the German’s jugular vein with his right. Porter lowered him to the ground, motioning the sign “move forward” as the column marched on speechless. They had gotten lucky.

The cold dawn illuminated the long column of tired, bedraggled soldiers as they made it past friendly lines into an old farming compound in the village of Soy. Frowns turned to grins as the waiting regimental cooks poured hot soup and coffee into ration tins and canteen cups. Big chunks of baked bread passed into hands still stinging with the first signs of frostbite. Combat camera crews were on hand to capture the unbelievable escape of a surrounded battalion from under the Germans’ noses.

With his men around him, face still camouflaged, his head bundled against the cold, Sam stood tall in front of Third Armored’s revered commander, Major General Maurice Rose. Sam didn’t know if he would get dressed down, relieved, or congratulated. Immaculately uniformed in taupe-colored riding breeches, polished knee-high riding boots and gleaming steel helmet in front of his disheveled subordinate, his hands on his hips, General Rose asked Sam in his business-like, commanding voice why he was the last one out. Sam thought of several heroic things to say and finally uttered the truth: “My feet hurt.” General Rose cracked a rare smile, patted Sam on the back, and returned to his Jeep. After a short tactical road march, Hogan’s 400 camped at Barvaux, where they remained through the New Year to reequip and reorganize.

Back in surrounded Marcouray, Doc Spigelman woke to a clear, quiet dawn surrounded by his two medical sergeants and the 17 wounded troopers. The ruse had worked. The Germans still believed the town occupied. As planned, he assembled his motley crew of wounded soldiers and prisoners and, under a Red Cross flag, began marching out of town trying to reach U.S. lines on their own. They reached the first German roadblock, where astonished sentries attempted to detain them. With his Yiddish and pointing to the Red Cross flag, Spigelman was able to pass that and two more checkpoints until upon reaching the final one, where they were held until “completion of our upcoming attack.”

The German attack did not go as planned; by then word had gotten back that the American battalion holding up progress at Marcouray had exfiltrated to its own lines. Doc and his wounded soldiers became prisoners of war. Doc remained a prisoner for four months, escaped, was recaptured, and finally was liberated by US forces at the end of the war.

Overnight, Hogan’s 400 and Task Force Hogan became household names, and the story of their intrepid breakout made the Stars and Stripes and then state and national news. Sam’s wife and her girlfriends giddily awaited the newsreels at the local cinema to try and catch a glimpse of Sam’s camouflaged face among his 400 men. The legend of Task Force Hogan was cemented as the unit broke out of its “mini-Bastogne” on Christmas night and rejoined Spearhead to counterattack and pinch off the Bulge. For Sam and his soldiers, there was no time for accolades. They scribbled short letters home telling their loved ones that they had survived Hitler’s last gamble in the West, then prepared for some payback.

Sam’s boys received new equipment. Marcouray or “Hogan’s crossroads,” as it was being called by division troops, was retaken by other Spearhead elements on January 7, 1945. The Germans had not been able to use any of the equipment left behind. Task Force Hogan, rearmed with only 12 medium and 10 light tanks, plus supporting Infantry of the 83rd “Thunderbolt” Infantry Division, moved out for some payback across roads choked with German vehicles destroyed by U.S. artillery in the preceding weeks.

Ten miles to the south, the First and Third U.S. Armies linked up. The lost ground regained and the Bulge eliminated, Montgomery sent the following secret cable to General Dwight D. Eisenhower, the supreme Allied commander:

“I have great pleasure in reporting to you that the task you gave me in the Ardennes is now concluded. First and Third Armies have joined hands at Houffalize and are advancing eastwards. It can therefore be said we have now achieved tactical victory within the salient. I am returning First Army to Bradley tomorrow as ordered by you. I would like to say what a great pleasure it has been to have such a splendid Army under my command and how very well it has done.”

During the Battle of the Bulge, Spearhead sustained losses of 125 medium tanks, 38 light tanks, and 1,473 casualties including 187 killed in action. For Hogan’s 400, the war was far from over. There remained another four and a half months of hard fighting, fatigue, sleepless nights, and the loss of close friends, but the U.S. Army had withstood the largest offensive directed against it in the entire war.

William R. Hogan is a fourth-generation U.S. Army officer who has served across the world from Bosnia to Haiti and Afghanistan. He is the youngest son of Colonel (Ret.) Samuel M. Hogan and is completing a book on the exploits of Task Force Hogan from Normandy to the Elbe. He currently resides in Paris, serving as an exchange officer on the French Army Staff.

The Bulge could have been very different . The Sixth Army Group under General Devers was the first to reach the Rhine at an unopposed bridge in mid November 1944 . Ike ordered Devers not to cross. Had he done so ,the Sixth Army Group may have very well flanked the german forces in hiding for the surprise attack Don’t forget that air power may have decimated the enemy had they been discovered in time . Most readers will blame Ike for the decision ,which was supposedly due to bad blood between the two that happened when Devers was Ike’s CO . I am more convinced that FDR gave that order to Marshall for Ike that made the Sixth Army Group stand down . He had a sweet relationship with Stalin .