By Kevin M. Hymel

Almost every soldier on western European battlefront wanted to get to Paris. Once it was liberated on August 25, 1944, it became a mecca for Allied soldiers on leave who filled the streets, bars, and historic buildings, enjoying a brief respite from the war. American soldiers, with their vast numbers and deep pockets, made up most of the crowd.

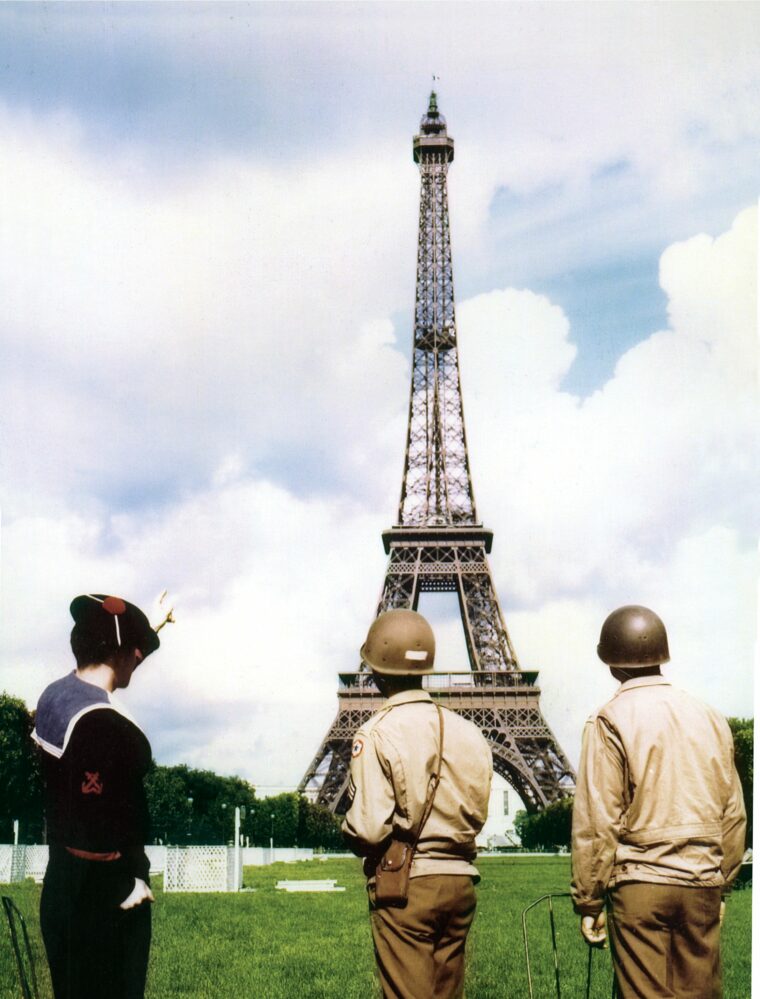

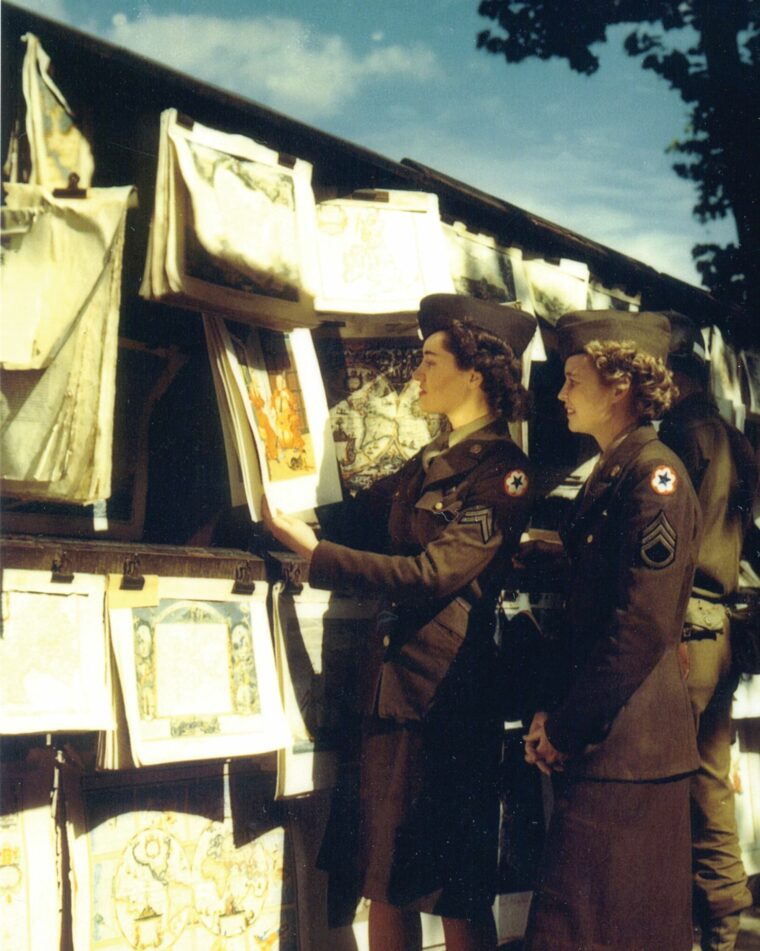

American men and women from farms, small towns, and big cities enjoyed strolling down the Champs Elysees, touring Notre Dame, watching the exotic dancers of the Follies Bergère, or riding an elevator to the top of the Eiffel Tower. Some shopped in the open-air markets, others were content to sip coffee at an open-air café. Nights were filled with dancing and drinking some of finest wines and champagnes the country had to offer.

One GI referred to his time in Paris as “a glorious world of wine, women and song.” Another remembered, “The women danced on piano tops, we all got high and kept singing the ‘Marseilles’ even though we didn’t know the words.” Lieutenant Andrew Tuck, a paratrooper with the 101st Airborne Division, wrote his family about drinking cognac in a café: “result: mild paralysis.”

But there were still signs of war: Antiaircraft guns throughout the city pointed skyward; military policemen moved traffic, secured military buildings, and maintained order; and buildings still bore the scars from the street fighting. Of course, every night, when the sun went down, the whole city was blacked out. The lights would not come on in the City of Lights until the end of the war, when everyone could enjoy a truly free Paris.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments