By Allyn Vannoy

On September 5, 1944, American intelligence estimates of German forces in the sector of the 80th Infantry Division, between Nancy and Metz in northeastern France, described scattered units and limited defenses along the east bank of the Moselle River. Elements of the 3rd and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions were reported to be withdrawing through the area as German Army Group G attempted to gather Panzer units behind the front.

American forces were able to reach the Moselle with little opposition. However, the first crossing attempt by the 80th Division at the village of Pont-á-Mousson, halfway between Nancy and Metz, failed due to the lack of air or artillery support and stronger-than-anticipated German defenses. The next day, another attempt near the village of Pagny was made simultaneous with a crossing effort at the village of Pont-á-Mousson, but the current was too swift and German artillery fire was too accurate. Both attempts failed to secure bridgeheads.

After these failed crossings, the 80th Division withdrew a few miles to the west and commenced planning another effort, the date changing several times in order to allow for better reconnaissance of possible crossing sites. Meanwhile, on September 7, the German XIII Infantry Corps, under Lt. Gen. Hermann Priess, was assigned the Metz-Nancy sector. Forces opposing the 80th included the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division and the 92nd Luftwaffe Field Regiment.

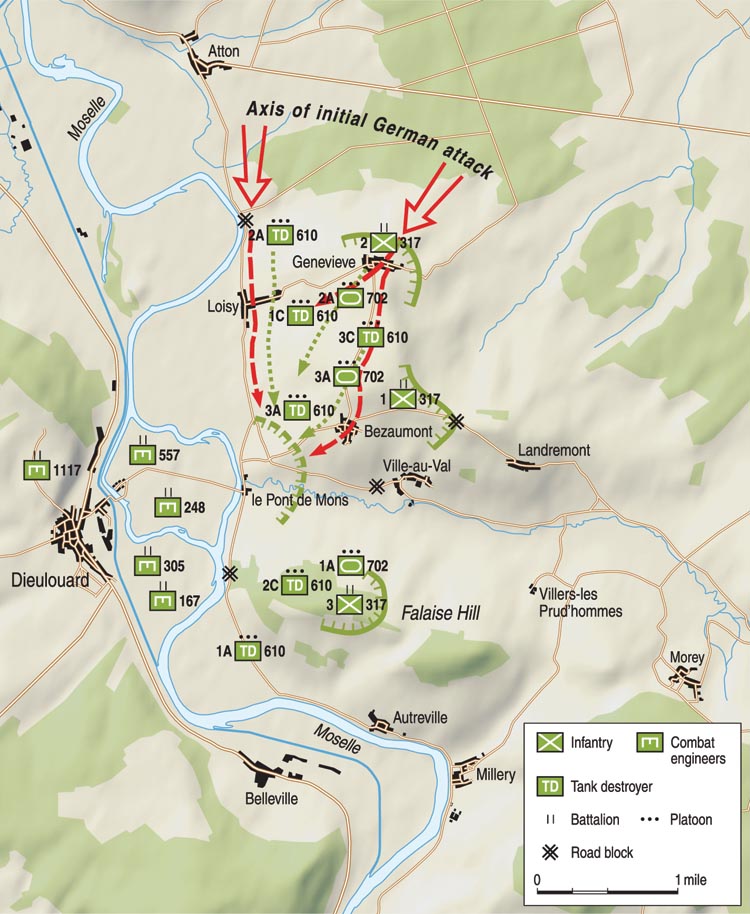

Seizure of a foothold across the Moselle south of Nancy by the U.S. 4th Armored Division on September 11 dictated a follow-up effort by the 80th Division to cross the river north of the city and initiate a left hook as part of XII Corps’s plan of concentric attack. Maj. Gen. Manton S. Eddy, XII Corps commander, gave orders for the 80th to carry out a crossing near the town of Dieulouard and open a bridgehead for Combat Command A (CCA) of the 4th Armored Division to advance into the rear of German forces and create a pocket around Nancy.

Officers of the 80th

After the previous failures, Maj. Gen. Horace L. McBride, 80th Division commander, laid plans for coordinated operations. McBride was a tall, slender man who looked like a farmer. He had a fiery temper and was not well liked by his men. In the new plan, the 317th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel A. Donald Cameron, would be responsible for seizing the river crossing at the industrial river town and securing a hold on the enemy’s eastern bank. Its initial objective was the series of hills and ridges immediately east of Dieulouard. Cameron was a husky, broad-faced man who was calm under fire. He had seen service in China and in Siberia at the close of World War I, and he had remained in the Army during the interwar years, helping to reactivate and train the 80th Division at the start of World War II.

Once elements of the 317th were across, two battalions of the 318th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Harry D. McHugh, were to follow, wheel north, and capture the area’s dominant elevation, Mousson Hill near Pont-á-Mousson. CCA, 4th Armored, would assemble behind the 80th, cross through the infantry bridgehead and strike hard for Château-Salins, a strategic road and rail center 23 miles east of Nancy. To add weight to the armored drive, the 1st Battalion, 318th Regiment, was given motor assets and attached to CCA. As a result of these detachments, McBride could count on only five of the division’s nine infantry battalions for crossing and bridgehead operations. Engineering support was to be provided by the division’s engineer unit, the 305th Engineer Combat Battalion, supported by the attachment of the 1117th Engineer Group, which included the 167th and 248th Engineer Battalions.

Challenging Geography

The German-held ground presented a difficult problem for the Americans. The area was a rolling plain dominated by frequent outcroppings of high hills with scattered clumps of woods and a few tight, deep forests. One of the American officers likened it to West Virginia—steep descents with cuts, dropping off abruptly to the flood plain of the Moselle. The area was dotted with ancient fortifications, providing the German defenders with ready-made strongpoints. Along the west bank of the Moselle, a series of woods screened the American assembly areas north of Dieulouard. But the roads cutting between the forests were under the watchful eyes of the Germans perched on the eastern shore hilltops at Mousson, Geneviève, and la Falaise. Every draw and gully was zeroed in.

The Moselle meandered in the vicinity of Dieulouard as it flowed northward. A crossing would require bridging parallel waterways. Along the western bank of the river was a barge canal, 40 to 50 feet wide and six feet deep. Between the river and the canal was an eight-foot-high dike. Opposite Dieulouard the river split, with the main channel flowing by the town and the eastern branch of the river, the Obrion Canal, forming two arms that wound around a flat island, a little less than 2,000 yards across at its widest point. On the east bank the ground sloped upward gently for 200 yards, then became very steep, varying in grade from 15 to 20 degrees near the villages of Ste. Geneviève and Bezaumont to approximately 30 degrees on Mousson Hill to the north.

The villages of Landremont and Ville-au-Val sat on the southern slope of the Ste. Geneviève Ridge. Landremont, at 200 feet elevation, was situated on an eastward extension of Geneviève Hill, while Ville-au-Val was located on the lower, southern slope of the hill. Falaise Hill, also referred to as la Falaise, dominated the country to the south.

The terrain in the region was generally unfavorable to tank warfare. The steep heights and numerous wooded areas channeled armored movement along well-defined avenues; roads were frequently bounded on one side by deeply ditched streams and on the other side by rises too steep for tanks to climb, further limiting deployment and dispersion. The river itself varied in depth from six to eight feet and flowed at approximately six to seven miles per hour. The muddy bottom of the river made fording perilous for vehicles. The average width was 150 feet. The river banks were low but still required grading with bulldozers to make them accessible. There were few fords available for infantry. The heights on the east bank of the Moselle were crowned by remains from historical campaigns. On Mousson Hill lay the vestiges of a medieval church-fortress, near Ste. Geneviève. Celtic earthworks could still be found on the crest, and the ruins of a Roman fort sat atop Mount Toulon.

Composition of the 80th Division

As with most American infantry divisions, the 80th was provided with several attachments. The 610th Tank Destroyer (TD) Battalion (towed), equipped with “obsolete” 57mm antitank guns, operated in direct support of the 80th. The battalion’s three companies were distributed among the infantry regiments. Other attachments included the 702nd Tank Battalion, Lt. Col. Ralph Talbot commanding. The battalion, like the tank destroyers, was parceled out among the regiments. Eight battalions of artillery were assigned to support the crossing—the division’s organic 105mm howitzer battalions (313th, 314th, and 905th Field Artillery Battalions) and the 315th Field Artillery with 155mm howitzers. Artillery battalions from XII Corps included the 512th, 974th, 775th, and 176th.

From September 7 to 11, reconnaissance patrols were organized by both engineers and infantry to search out the best bridging and crossing sites. Since tactical surprise was considered vital for the success of the coming attack, patrols were limited. Major James H. Hayes, the 317th’s intelligence officer, personally led several such patrols. Cameron also made extensive reconnaissance forays to select sites for the crossing. Lt. Col. L.E. Fisher, executive officer of the 317th Infantry, recalled: “He made me defend every reason I could give for making the crossing at this point. Most of the talking and planning was done on the basis that we could gain tactical surprise with key terrain. We had two objectives: the first, Bezaumont-Ste. Geneviève; the other, la Falaise.”

Engineering the Crossing

It was decided to use assault boats as well as available river fords for the crossing. The Americans hoped the Germans would consider the Dieulouard area the least likely spot for a crossing since it would entail crossing three separate bodies of water. The island in front of the town would provide protection if the Germans attempted to cut off the bridgehead. The engineers planned to bridge the barge canal at two places and then span the river at several key crossing points.

The attack was scheduled for 0400 hours, September 12. The 2nd Battalion, 317th Regiment, crossing north of the island, would pass over the floodplain. Once on the eastern bank, it was to push through the village of Loisy, then move to Geneviève Hill and the village of Ste. Geneviève. The 1st Battalion would follow using the same crossing site, then move to the right and secure Hill 382 northeast of the village of Bezaumont. The 3rd Battalion would cross the river south of Dieulouard, transit the island and the far arm of the river, then move right and secure the high ground on la Falaise.

The two battalions of the 318th Infantry, acting as a reserve, were to cross the Moselle after the 317th, occupying positions 500 yards west of Bezaumont and below the western slope of Hill 382. The 318th was to be prepared to extend the bridgehead. Support fire from the west bank was to be provided by massed machine guns emplaced along the edge of the Bois de Cuite, near the northern crossing site. The machine-gun emplacements were well camouflaged and directed by field phones.

The 305th Engineers were responsible for crossing foot elements, the 1117th Engineer Group for the vehicular traffic. Company B, 305th Engineers, was to expedite construction of a foot-bridge over the canal, guide the assault waves of the 2nd Battalion, 317th Division, across the river in assault boats, then follow up by constructing a footbridge over the Moselle. Company A, 305th, minus one platoon, was to guide the 3rd Battalion, 317th, over the canal and across the fords to the island.

Company A, 167th Engineers, was to bridge the canal and river with portable trestle bridges, adequate to carry half-tracks and heavy trucks. These were to be pre-fabricated in bivouac areas, carried to the sites in trucks, and put into place as soon as the area was clear of small-arms fire. Company B, 167th, was to construct a pontoon bridge across the canal and throw the heavy pontoons across the river late on the 12th, after German artillery observers had been pushed off the surrounding hills.

0400 Hours

Preliminary to the 80th Division’s attack, on the afternoon of September 11, Allied aircraft began a feint at the Pont-á-Mousson area to divert German attention from the intended crossing site. Artillery joined in and continued to shell Pont-á-Mousson during the night. The battalions of the 317th moved out at dusk on the 11th to assembly areas in the Bois de Cuite. Road markers had been placed and guides posted along the route to the river. Blinker lights had also been set at the river fords.

In a drizzling rain, the ambitious crossing operations jumped off at 0400, as the 50 machine guns at the edge of the Bois de Cuite put a curtain of fire over the heads of the assault waves. The 3rd Battalion traversed the island, moving quickly to the Obrion Canal. On the left, at a crossing site about 500 yards north of the island, the 2nd Battalion was hit by mortar fire and briefly disorganized, but the first wave soon reached the Moselle.

At 0430 hours, the artillery battalions laid down their 15-minute preparation, firing two rounds a minute. At the same time, 30 rounds of white phosphorous were placed on the town of Bezaumont, setting the town on fire, in order to act as a guide for the GIs. As the infantry advanced across the river and up to the river road, the barrage was raised. After the initial barrage, 19 more concentrations were fired at preselected targets.

The 3rd Battalion, 317th, forded the Obrion Canal and by 0530 had possession of its first objective, la Côte Pelée, south of Bezaumont. At 0755, the 2nd Battalion, 317th, seized its objective, Geneviève Hill. During the infantry crossing the Germans reacted only with occasional fire from weak outposts on the river. The slow German reaction was also influenced by the drizzling rain, which reduced visibility, and the moving barrage laid down ahead of the attacking infantry, which knocked out communications and dispersed the few local reserves.

By 0830, the 1st Battalion, 317th, commanded by Lt. Col. Sterling S. Burnett, was at its objective in the vicinity of Bezaumont. Sergeant Charlie W. Brown, a squad leader with Company A, 305th Engineers, vividly remembered the crossing: “We jumped into some boats that took us across and dumped us out. After a heavy barrage on the hill, we took off across some table top ground toward a road where the Germans were set up in the ditch. We advanced into their fire until we reached a pasture fence about 50 yards from the road, where we came to a complete halt. We were all afraid to get up and get over the fence. I could see the grass getting ripped up on all sides. A man next to me was hit. I could see what we were up against and thought of the engineer side cutters. Grabbing the cutters, I ran down the fence cutting the top two or three strands in front of the infantry. About half way, I threw the pliers to another man and took off across the field like a short John Wayne, the squad right behind me. An infantry officer rallied his men and he was right with us when we overran some Germans in a ditch. A German medic raised up out of the ditch and in the confusion was shot down. A second line of defense started firing from high on the hill. A machine gun was firing from a clump of brush. We had all zeroed in on it as we were still climbing the hill. Suddenly two men dashed out carrying a machine gun. The trailing soldier got hit, and when the other came back to help him, all of our firing stopped like it had been turned off with a switch.”

Company G, 317th, dug in to hold Ste. Geneviève with two platoons supported by a machine-gun platoon from Company H. The third platoon of Company G was extended to the south on the forward slope of the hill and tied in with Company F, whose lines extended further south. Company E, in support, was echeloned to the right rear of Company F.

The 2nd Battalion, 318th, under Lt. Col. John C. Golden, crossed the river between 1000 and 1100 hours and moved to a position 1,000 yards northwest of Bezaumont. Company G, led by Captain John B. Kelly, 318th, had been left on the west side of the Moselle, south of Dieulouard, to guard the river, and 2nd Battalion’s forces across the river consisted of only two rifle companies and its heavy-weapons company.

Bridging the Canal and the River

Bridging operations had proceeded according to plan. The speed and ease with which the American infantry had advanced during the morning led McBride to order the engineers to begin work to bridge the canal and both river arms with heavy pontoons as soon as possible, rather than waiting for the area to be declared free from artillery threats. By 1500, the 167th Engineers had completed their infantry support bridge over the near arm, putting tank destroyers and trucks loaded with ammunition across to the island. Company A, 557th Heavy Pontoon Battalion, commenced work on the canal bridge at 1000 and completed it in three hours. The company then moved on to work on the heavy pontoon bridge across the near arm of the river, commencing work at 1300 and completing it in five hours. The bridge over the far arm was completed in just four hours, and by 2000 the canal and both arms had been bridged with heavy pontoons. After completing their work, three companies of engineers set up defensive positions near the bridge sites.

The 318th Regimental Cannon Company had not been included in the initial crossing schedule, but its CO, Captain Frederick H. Lewis, used a bottle of whiskey to persuade the officer directing traffic across the bridges to permit his unit to cross. When an opening occurred in the traffic moving across the bridges, the traffic control officer signaled to Lewis, who had his trucks and towed cannons lined up and ready to move. The column raced down to the bridge and headed across. The company’s three ammunition trucks were so heavily loaded that Lewis instructed the drivers to set their throttles and stand on the running boards in case they sank in the river. In this way, they got across with 1,400 rounds—more than three times the unit’s basic load.

Lewis directed the column to a position was just south of Bezaumont near the road to Ville-au-Val. The 2nd Battalion, 317th, was to their left front and the 3rd Battalion, 317th, to their right, both occupying high ground. Cannoneers were dispersed for defense with bazookas and .50-caliber machine guns.

At 1600 hours, roadblocks were set up at Ville-au-Val and le Pont de Mons, manned respectively by Companies I and K, 318th. Likewise, Company F, under Captain Frank A. Williams, was sent to man a roadblock north of Loisy, while Company E, commanded by Captain Charles C. Matlick, moved to cover the road east of Bezaumont. Left in reserve at the 2nd Battalion CP were 30 men, along with the CP group, the mortar platoon of the heavy-weapons company, and Company L, just north of the buildings at the east bank crossing site at le Pont de Mons.

The 318th Regimental HQ had moved over the river at approximately 2000. After crossing, the headquarters convoy started north toward Loisy as it grew dark. When it was discovered that the HQ staff should have been headed south to a preselected site, the convoy halted in place and a temporary CP was established at the junction of Ville-au-Val and the river road. The terrible consequences of the misstep would be borne out that night.

When Company C, 610th TD Battalion, reached the east bank, its platoons were disbursed at various points in the bridgehead. Company A’s platoons were directed to support the widely separated roadblocks. At 2230, the 702nd Tank Battalion commenced crossing the river. The battalion had some difficulty due to intermittent German shelling, but did not suffer any losses.

By the time the tanks had crossed into the bridgehead it was dark, and guides from the infantry battalions met each tank platoon as it came off the bridge and led them to pre-planned positions.

Company A, 702nd, under 1st Lt. Francis L. McDermott, was parceled out, with one platoon per battalion. The 1st Platoon, led by 1st Lt. James Atkins, moved to an open slope south of Ville-au-Val, where the Shermans were positioned in pairs about 75 yards apart. The 3rd Platoon, under 1st Sgt. William E. Murray, was guided up Hill 382 to a position west of the Ste. Geneviève-Bezaumont, just south of some ruins. Meanwhile, Lieutenant John Croxton’s 2nd Platoon took up a position in a patch of woods southwest of Ste. Geneviève, just north of Murray’s position. Company B, 702nd, Lieutenant Francis P. Ford commanding, crossed directly after Company A and proceeded a short way up the road to Loisy. Placed in reserve, the company halted in an orchard near the river and set up a defensive perimeter.

The German Counterattack

From about 1500 hours, the Germans had begun to lay down artillery barrages on American positions at Ste. Geneviève, le Pont de Mons, and Loisy. By 2230, the barrages reached a point of terrific intensity while mortars methodically worked over the reverse slopes. Meanwhile, a considerable furor had erupted at the headquarters of the German First Army when word was received of the American crossing. First Army commander Lt. Gen. Otto von Knobelsdorff dispatched an infantry battalion, reinforced with assault and antitank guns, to Benicourt in the hope of stopping the Americans on the road to Nomeny. He sought permission from General Johannes Blaskowitz, Army Group G, to evacuate Nancy, reasoning that the bridgehead had to be erased, even at the cost of endangering the southern flank of the army. Blaskowitz gave his grudging assent to move three infantry battalions north from Nancy. At the same time, Knobelsdorff dispatched two battalions of the 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division from Metz in order to reinforce the 3rd Panzergrenadier Division. The 3rd Panzergrenadier may have been the best unit on the West Front at the time. The division was a veteran unit that had been recently transferred from Italy. It had a combat efficiency rating of Kampfwert II, a rating given only to the best German divisions on the front since virtually none could be graded as capable of sustaining an all-out attack—Kampfwert I.

The first warning of an intended attack came at 0130 when Captain Williams, Company F, 318th, manning the roadblock north of Loisy, reported enemy infiltration into his positions and around his right flank. At 0200, Williams reported eight tanks coming toward his position with an infantry force estimated at battalion strength. The roadblock held until 0330, when Williams notified his headquarters that his position was untenable. He was ordered to withdraw and conduct a delaying action.

At 0300 hours, artillery and mortar barrages preceded German infantry as they moved through the positions of the 2nd Battalion, 317th, and enveloped the left platoon of Company B, 317th, led by Captain Robert W. Mudge. At the same time, the 1st Battalion, on the high ground northwest of Landremont, repelled a German attack from the southeast. The main German assault came through Loisy and Ste. Geneviève and included two battalions of the 29th Panzergrenadier Regiment, reinforced with 15 tanks and assault guns. One German column struck from the northeast through Ste. Geneviève and moved southwest; another moved south along the ridge toward Bezaumont. Company G, 317th Infantry, was forced from its positions at Ste. Geneviève, falling back on the 318th. Companies E and F fought a fierce action to hold their positions.

A force estimated at company strength ran into the positions of Company E, 317th, and was shot down at ranges of less than 40 yards. At daybreak, a group of about 45 Germans was trapped between Companies E and F. Twelve were killed by small-arms fire, the remainder surrendered.

At about the same time, elements of Company G, 317th, passed through the positions of the 2nd Battalion, 318th. Some of the retreating soldiers said that they had been attacked by tanks and infantry and that the Germans had overrun their positions. Simultaneously, a report was received that German tanks were coming down the road from Loisy. It was decided to withdraw to a point just forward of le Pont de Mons. Some of the retreating GIs were stopped by the 318th regimental executive officer, Lt. Col. Roy J. Herte, who had decided to build a line along the river road. Captain Charles F. Gaking, S-3 of the 2nd Battalion, 318th, approached Herte to discuss plans. As the two officers were talking, a Mark IV panzer came around a bend in the road from Loisy and opened fire, causing the nearby GIs to take cover in a roadside ditch. Armed only with carbines and pistols, they could do very little. As the panzer came on, a few men surrendered. A second panzer then appeared about 50 yards behind the first, accompanied by infantry. At 0500, the rest of the Americans in the vicinity surrendered, Gaking among them.

To the Last Man

While German infantry assaulted the TDs, the panzers attempted to go after the infantry. As soon as gun positions were sighted, the German infantry used flares to blind the American crews and then move around them in order to assault the positions from the flanks and clear a path for the tanks. The panzers, in turn, sprayed any suspicious-looking clump of bushes with fire.

The TD battalion formed two bazooka teams and went forward to provide support. As the panzers came under fire, the Germans swung away to avoid the bazookas, but in so doing they ran into fire from the tank destroyers of the 3rd Platoon, Company C. Five German panzers were destroyed, with bazooka fire accounting for one.

The 702nd Tank Battalion reported three German thrusts coming from the Forêt de Facq into the bridgehead, each consisting of a platoon of tanks or assault guns supported by at least a company of infantry. One was directed through Ste. Geneviève, across the ridge toward the town of Bezaumont. Another was aimed through Ste. Geneviève, downhill to Loisy, then southward to the bridge site. The third came down through Atton, heading south along the river road. The bulk of the American infantry was virtually unsupported on the forward slopes of Geneviève Hill and Hill 382, the tanks and TDs having been positioned on the reverse slope.

At 0515 hours, the CP of 1st Battalion, 317th, approximately 300 yards behind the main line, was attacked by a 12-man German patrol. The patrol was neutralized and all its members were killed or captured. At 0600, a German assault gun moved on the positions of Company C, 317th, commanded by Captain Grant E. Hoover, crushing a 57mm antitank gun before it was knocked out by a three-inch gun of the 610th TD Battalion. Giving no quarter, the Americans shot down the survivors of the assault gun crew as they attempted to escape from their disabled vehicle.

At 0515 hours, the CP of 1st Battalion, 317th, approximately 300 yards behind the main line, was attacked by a 12-man German patrol. The patrol was neutralized and all its members were killed or captured. At 0600, a German assault gun moved on the positions of Company C, 317th, commanded by Captain Grant E. Hoover, crushing a 57mm antitank gun before it was knocked out by a three-inch gun of the 610th TD Battalion. Giving no quarter, the Americans shot down the survivors of the assault gun crew as they attempted to escape from their disabled vehicle.

Corporal Martin F. Loughlin, a gunner with the 318th’s Cannon Company, described an engagement with a German panzer: “Directly in front or our cannon was a small gully and about 50 feet away a narrow dirt road. East of the dirt road was a fairly steep hill. The shelling had slackened, but there was some mortar fire. I heard someone yell, ‘A German tank!’ At the top of Geneviève Hill was a German tank, possibly a Panther. It started down the hill toward us. Immediately, small-arms fire opened up. To my left was a battery of 105s. One gun crew ran, with the exception of a buck sergeant. He yelled and cursed for one of them to return as a loader. One did. Meanwhile the tank clattered slowly down the hill unsupported. It was firing antitank shells, which whistled into the trees or ricocheted off the ground. The 105 crew of two, loading and bore sighting, was firing high explosive shells which exploded near some dug-in riflemen. On it came. With mouth agape, just holding my carbine, I watched as the tank attempted to cross a road a scant 70 feet away. As the tank’s exposed belly came up over a small ditch there was a tremendous explosion. The tank staggered, shuddered and burst into flames. An unseen, towed 76mm tank destroyer to our right had patiently waited for a belly shot and had nailed the tank. Two of the tank crew got out. One was cut down by a .50-caliber machine gun from the artillery battalion just as he got out of the tank. The other slid off the tank, but was killed by riflemen.”

Major James Hayes, the 317th’s S-2, and Colonel Cameron went to Dieulouard at about 0600 as the German attack was in full swing. Seeking to cross over to the east bank, they were prevented from doing so by combat engineers manning machine-gun positions along the river. The engineers warned Hayes that everything had been wiped out across the river and that they were prepared to defend to the last man.

Cameron instructed Hayes to take a patrol across the river and establish communications with the 2nd Battalion, 317th. Hayes crossed the river and managed to make his way to Hill 382. Germans seemed to be everywhere. No one knew the exact location of the 2nd Battalion. While attempting to get to Bezaumont, Hayes’s patrol came under fire from enemy tanks and so elected to bypass the town, but in doing so came under fire from their own artillery. Hayes recounted: “We started up the hill toward Ste. Geneviève and ran into one of our tanks roaring down the hillside out of control. It was on fire and was one of the most shocking sights we had seen. It almost ran into us as we went up the draw. We pulled up a little onto the hillside and watched it pass, the dead crew hanging out of the turret. It exploded far below.”

Confusion Among the Defenders

At daybreak, defensive lines were in the process of being formed at the base of Hill 382. A colonel of the 317th threatened to shoot any infantrymen who continued to fall back. As a result of the confusion caused by the attack, the American units became mixed. Engineers, TDs, tanks, and infantry were thrown together. Communications were disrupted. Officers, regardless of unit or branch, jumped into the fray, taking command of small groups of men as they presented themselves and marshaling them into line to meet the German attack. Majors commanded platoons and captains directed battalions.

Radioman W.A. Rose related events at the 318th CP: “After a heavy artillery barrage, we learned that the Germans had counterattacked. Everything was in a state of confusion, men running back and forth trying to get our vehicles and equipment to safety. We formed a line and attempted to hold back the attack. Unknown to us, a German tank had moved in on our left flank and opened fire at less than fifty yards. We had antitank men, wiremen, radio operators, headquarters personnel. The German tank crew fired several flares, revealing our position, and we were forced to move back. While the third flare was in the air, I was able to see that we were near a road, and also to see the ditch near the road. This I intended to head for when the flare went out. After running several yards in the dark, I dove into the ditch. As I flew through the air, and just a moment before I hit the ditch, I felt a hot stab in my chest. Later, I opened my jacket and discovered that a bullet had gone through the pocket on the left side of my shirt, right over my heart, cutting letters, pictures, pay book, but had not penetrated the skin.”

Radioman W.A. Rose related events at the 318th CP: “After a heavy artillery barrage, we learned that the Germans had counterattacked. Everything was in a state of confusion, men running back and forth trying to get our vehicles and equipment to safety. We formed a line and attempted to hold back the attack. Unknown to us, a German tank had moved in on our left flank and opened fire at less than fifty yards. We had antitank men, wiremen, radio operators, headquarters personnel. The German tank crew fired several flares, revealing our position, and we were forced to move back. While the third flare was in the air, I was able to see that we were near a road, and also to see the ditch near the road. This I intended to head for when the flare went out. After running several yards in the dark, I dove into the ditch. As I flew through the air, and just a moment before I hit the ditch, I felt a hot stab in my chest. Later, I opened my jacket and discovered that a bullet had gone through the pocket on the left side of my shirt, right over my heart, cutting letters, pictures, pay book, but had not penetrated the skin.”

Gaking and His Men Escape

The Germans herded together the prisoners from the 318th HQ and Company F, captured along the road from Loisy, and forced them to follow their tanks in the direction of the attack. As the German columns converged on the bridge site, they ran headlong into the tanks of Company B, 702nd Tank Battalion, and a half-track mounted with quad .50-caliber machine guns from the 633rd Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion. The tank and machine-gun fire was devastating.

To Captain Gaking, still a prisoner, it seemed as though the Americans were attempting to pin down the Germans and surround them. Gaking and the other prisoners took cover in roadside ditches along with German infantry. Gaking tried to delay the Germans when they attempted to crawl along the ditch by occasionally standing up in order to draw fire from his own guns. Eventually, Gaking and five others escaped from the Germans and made their way back to the American positions.

Lieutenant Colonel John Golden, 318th, had his own recollection of events of that morning: “The order was given for the 2nd Battalion CP group to withdraw to the 3rd Battalion area and form a line to defend against the oncoming counterattack,” he recalled. “Arriving at the 3rd Battalion area at 0430, the German infantry had already infiltrated that position and had dispersed Company L. We moved back to the position where I thought the Regimental CP to be located. We went about 300 yards up to the Regimental CP, where we found most of the CP personnel dead. The ditches were full of wounded.”

One German column moved down the road from Bezaumont, threatening to overrun the crossing site at le Pont de Mons, cutting off and pinning units against the river. In the vicinity of le Pont de Mons was Company I, commanded by 1st Lieutenant Claude R. Fountaine, and the reserve platoon of Company K. Personnel were stopped from fleeing across the footbridge to the west or swimming the river, and placed in position to make a stand in and around the buildings.

Aftermath

The presence of the Shermans of Company B, 702nd, seemed to come as a complete surprise to the Germans, breaking the back of their assault. Captain Nordstrom recalled: “Company B had crossed the Moselle very late at night and set up a semi-circle defense near the bridge, with the tanks placed 20 to 30 feet apart. The company was to move into the line the next morning. The Germans came very close to wiping out the bridgehead. Company B shot them to pieces. The company really saved the division on this day. The American troops were all over the place, mostly running like hell. Company B was aided by some anti-aircraft guns near the bridge.”

By 0835, the attack had been halted, with the Germans suffering heavy casualties. Two hundred were taken prisoner, including members of the 29th Panzergrenadier Regiment, 1121st Grenadier Regiment of the 553rd Volksgrenadier Division, and the 1553rd Sturmgeschütz Battalion. Many were found to have no combat experience, having only recently arrived from training centers in Germany.

The attack had spent itself, the Germans having no fresh troops to provide the added impetus needed to push the last 200 or 300 yards to the bridge site at le Pont de Mons. With the coming of daylight, the Germans began to withdraw toward the north. The sacrifice of the 318th CP had delayed the German advance along the river road and bought time for the units in the bridgehead to organize and prepare a defense at the crossing.

Fighting near Dieulouard would go on for more than a month as the 80th Division continued to consolidate positions and expand the bridgehead, with the Germans weakening their defenses around Metz and Nancy in an effort to eliminate the crossing. The success in holding the bridgehead was in large part due to the will and sheer nerve of the individual fighting men of the 80th Division and attached units. Captain Marion C. (Woody) Chitwood, S-3 of the 3rd Battalion, 318th, said it best: “A great deal was done by the common GI—having been pushed as far as they were going to be pushed. For the most part, there was utter confusion. Daylight was about the only thing that saved the bridgehead. Our defensive preparations were inadequate, our communications were minimal, our command structure poorly positioned, and it became an individual effort in the midst of disorganization, darkness, noise, and fear. It wasn’t something you could be very proud of, but they did the best they could. There were a lot of casualties, but fortunately we were able to hold.” In the end, that was enough.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments