By Glenn Barnett

Much credit goes to the American ability to quickly manufacture the many ships and planes needed to fight the Pacific War and overwhelm the Japanese enemy. Less well known is the vital contribution made by ships from World War I that served during the century’s second global war. These unsung heroes also did their bit to win the conflict of 1939-1945. Among them was a Clemson-class destroyer laid down at Mare Island Navy Yard, Vallejo, California, in 1919.

In February of 1921, she was commissioned and named Zane (DD-337) after Marine officer Randolph Zane, who died of his wounds at the 1918 Battle of Belleau Wood. At 1,190 tons (1,750 tons fully loaded) she equaled the size of other destroyers of her time. However, destroyers would soon grow in size and power.

After fitting out and a shakedown voyage, Zane was assigned to Destroyer Division 14, which left California in June 1921, and steamed across the Pacific to the Philippines to join the Asiatic Fleet. Zane spent a year in Philippine waters before moving on to China. There she visited Shanghai and the crew was given leave in the capital city of Peking (now Beijing).

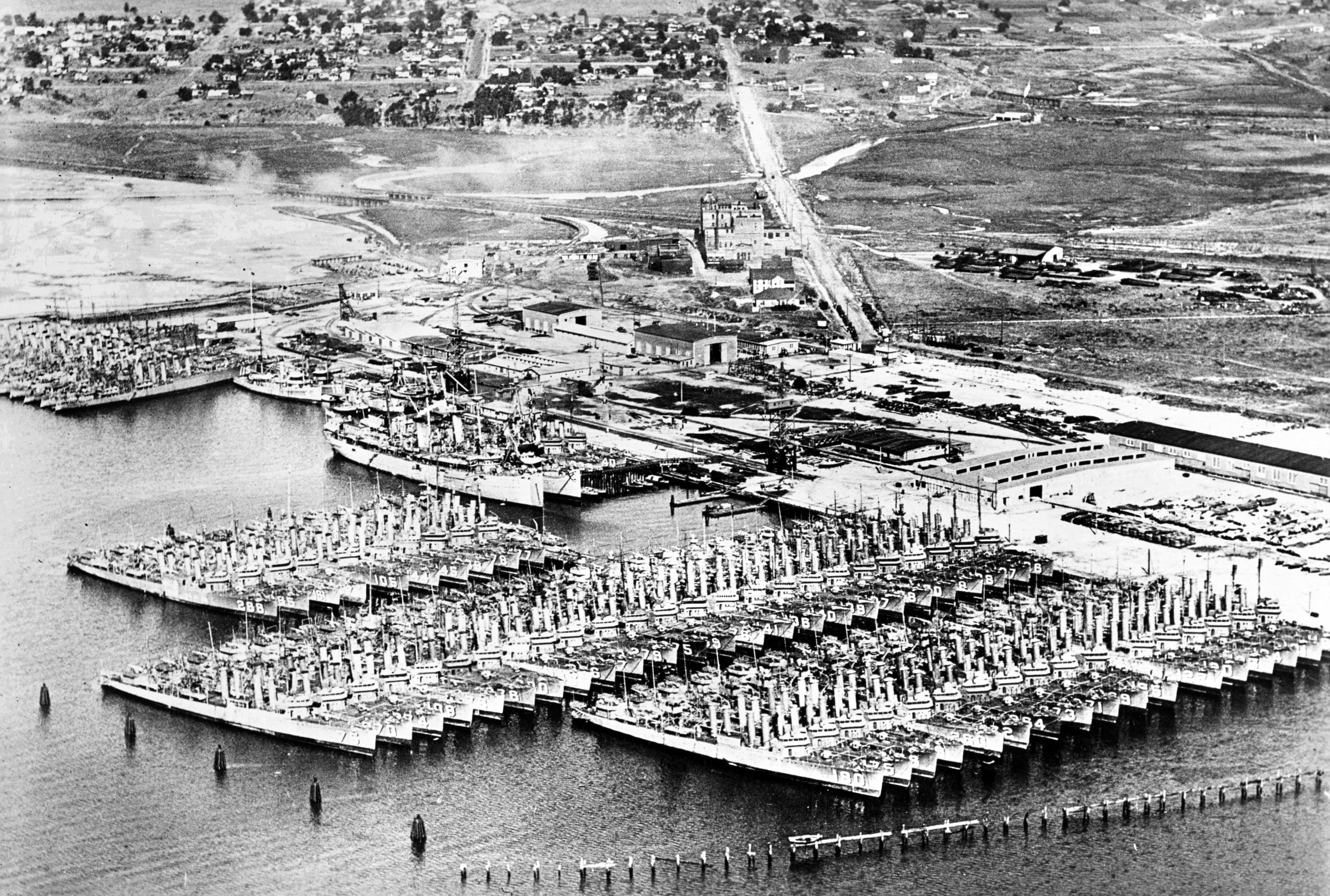

In August of 1922, Zane made a goodwill visit to Nagasaki, Japan, future target of the second atomic bomb, dropped on August 9, 1945, ending World War II, on the first leg of her voyage back to California. There she was put into the Reserve Fleet. The brand new ships that came on line too late for World War I were “mothballed” in several ports. Zane was stored in San Diego, California. During World War I and afterward, 267 destroyers were built. After the war, up to 120 of them were kept in limbo, moored side by side in San Diego’s Red Lead Row, as the area was called. Fifty old World War I destroyers would later be sent to Great Britain as part of Lend-Lease in the famous 1940 Destroyers-for-Bases Deal.

Zane was recommissioned in 1930 as a fleet destroyer. Meanwhile, new classes of destroyers were beginning to come available. The old“four pipers,” so named because of their quartet of stacks, or “flush deckers,” were being replaced on front line duty.

There was a need, however, for fast minesweepers. The older ships still had most of their design speed. Zane could steam at 35 knots if needed, while cruising speed was 15 knots. Eighteen of the World War I era destroyers, including Zane, were converted to that task. Eight others became minelayers, 14 were converted to seaplane tenders, and 32 were modified as fast transports.

The conversion work on Zane was done at Pearl Harbor and consisted of removing her torpedo tubes, replacing older 4-inch guns with new 3-inch dual purpose guns, and removing one of the four funnels. This made room for sonar gear and depth charge racks. The work was completed in November of 1940. She was no longer DD-337, but now designated as a “Destroyer Minesweeper” (DMS-14).

December 7, 1941, found Zane at rest on the north end of Pearl Harbor. She was quietly moored side by side in a nest with three of her sister ships, Trever (DMS-16), Wasmuth (DMS-15), and Perry (DMS-17). Zane was sandwiched between Wasmuth and Perry. On that lazy Sunday morning, 10 percent of her crew and 25 percent of her officers were enjoying shore leave.

At 07:57, a signalman on watch observed something odd. A single plane was making a long, slow glide toward the south end of Ford Island before dropping what looked like a bomb. Only as the plane flew off could the signalman see that it did not have American markings.

When the bomb exploded, it triggered the clarion call to battle stations throughout the sleepy fleet. Zane had a .50-caliber machine gun armed and was firing away in minutes. As a host of Japanese planes arrived from the north, Zane’s crew fired at any of them that came within range. The first wave of enemy planes disappeared before much resistance could be offered. All the while, Zane and most of the other ships began building up steam to get underway. Zane could not move until Perry, moored outboard of her, got underway.

This was still being sorted out when, at 08:30, a sailor observed a periscope moving through the water nearby. Zane’s gunners loaded a round in one of the ship’s three-inch guns and attempted to train the barrel on the suspicious submarine. But the gun’s aim was blocked by Perry. As it happened, destroyer Monaghan (DD-354) was underway, and she rammed and depth-charged the Japanese midget submarine.

Soon afterward, the second wave of the Japanese air attack began. Now antiaircraft fire poured into the sky from dozens of ships, often doing more damage to each other than to the enemy. Zane’s rigging and antennae were shot up by friendly fire.

When Zane and her sisters finally untangled their moorings at 09:10, they raced toward the entrance to the harbor and stood out to sea, where they conducted anti-submarine and anti-mine operations. By then the Japanese, declining to send a third wave, had departed. In all, Zane had expended 3,000 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition. The one unfired three-inch round, having been primed, was removed from the breech and thrown overboard as a precaution.

In the confusion and fear that followed that day of infamy, Zane conducted patrol duties in Hawaiian waters until April of 1942. She was then assigned to escort a convoy to California, where she underwent some repairs and upgrades before returning to Hawaii in June. Not long afterward, she was provisioned for a long journey. Her crew could only guess their destination as they steamed to the southwest.

Zane’s skipper at this time was Lieutenant Peyton L. Wirtz. He took his job seriously. One admiring junior officer fresh out of the Academy said of his commander, “He would spend innumerable hours, 36 hours at a stretch, on the bridge making sure everything was under control.”

In early August of 1942, Zane and four other minesweepers would be the first American ships the Japanese would see off the coast of Guadalcanal. The five ships, dodging inaccurate fire from shore, swept the impending landing sites in advance of the arrival of U.S. Marines executing the first ground offensive against the Japanese in World War II. No mines were found when the Marines went ashore on Guadalcanal on August 7.

The next day, an Australian coastwatcher warned of an approaching flight of Japanese planes. Zane, while maneuvering at sea, fired at a passing Mitsubishi G4M “Betty” bomber with its 20mm gun and shot it down. Wirtz ordered the ship to pick up survivors from the plane. When the Japanese pilot pulled himself onto the floating wreckage of his aircraft, he began firing his pistol at the would-be rescuers. The ship’s 20mm gun decided the issue.

During the first month of fighting for the island, Zane was tasked with patrolling and conducting mine sweeps in the waters off Tulagi and Guadalcanal. Wirtz and his crew spent long hours at duty stations. In September, they were given a new assignment. Much has been said about Japanese destroyers resupplying their troops on Guadalcanal with night supply runs from fast destroyers of the so-called Tokyo Express. Such activities were not limited only to the Japanese.

The U.S. Navy also used fast destroyers to deliver supplies to the embattled island. At the island of Espiritu Santo in the New Hebrides, Zane and Trever (DMS-16) loaded drums of aviation gasoline on deck along with torpedoes, ammunition, and other stores. This material was meant for the two PT boats they each had taken in tow. They reached Tulagi at 05:30 on October 25, 1942, and finished unloading after dawn.

By 09:00, a group of three Japanese destroyers, Akatsuki, Ikazuchi, and Shiratsuyu, were spotted in the gap between Savo Island and Guadalcanal entering the waters known to the Americans as “Iron Bottom Sound” during broad daylight. This was unexpected as the Americans ruled the sky during daylight hours. The three Japanese ships headed toward vital Henderson Field on Guadalcanal to bombard the airstrip in support of their land forces.

The enemy destroyers had loaded their guns with high explosive ammunition for use against land targets. Against ships the standard practice was to use armor-piercing shells. At first, Zane and Trever hid in a bay at Tulagi, but Trever’s captain, in charge of the two-boat flotilla, did not want to be “trapped like a rat.” He ordered the two boats to make a run for it. As they left the protection of Tulagi, they were spotted by the Japanese, who changed course to intercept them.

A deadly chase began. Each of the Japanese ships could bring two of their six 127mm/50 guns to bear, while Zane and Trever had but one 3-inch or 76mm gun mounted at the stern to reply. To make matters worse, the Japanese destroyers were newer and faster. They rapidly closed the gap from 21,000 yards to 9,200 yards. Shells began falling close to both American vessels.

Despite zig-zagging to throw off the enemy aim, a shell landed in one of Zane’s gun positions, killing three and badly wounding a fourth crew member. If it had been an armor piercing round, damage to the interior of the ship might have been much worse. Japanese shells also ripped up much of her rigging, and the antenna was knocked out. All of her halyards were splintered and useless, except one. Significantly, and symbolically, it was the spar that carried the American flag.

Thankfully, the Japanese broke off the chase. However, their distraction at chasing Zane and Trever allowed time for airplanes to take off from Henderson Field and oblige the enemy destroyers to retire quickly. Zane’s unintended sacrifice saved the Marines guarding Henderson Field from a bombardment meant for them.

Wirtz’s hard work and devotion to his ship paid off. He was promoted to the rank of lieutenant commander and awarded the Silver Star medal. His commendation read in part: “In addition to participating in the initial attack against the islands…Lieutenant Commander Wirtz frequently brought his ship into the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area in the face of persistent Japanese air raids in order to escort and protect vessels bearing reinforcements and supplies to Marine forces established on the island shore.” Wirtz was also given command of a brand new Fletcher-class destroyer, McDermut (DD-677). Zane would have seven commanders during World War II. None of those who followed was as popular with the crew as Wirtz.

Zane continued her nocturnal supply runs and convoy escort duties until she left for Sydney, Australia, for repair and R&R for the crew. While there, on January 22, 1943, the Japanese submarine I-21 torpedoed and severely damaged the Liberty Ship Peter H. Burnett. Her crew launched five lifeboats. Four of them were able to stay near the damaged ship, but one drifted some 90 miles away in the dark.

The next day, Zane received orders to proceed to the last reported position of the crippled steamer. She was aided by a Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boat of the Royal Australian Air Force in locating the drifting life boat and rescued the 14 men aboard. The Catalina then directed Zane to the Peter H. Burnett, and Zane began a tow of the damaged ship to Sydney harbor in tandem with the Australian corvette HMAS Mildura.

In February 1943, with Guadalcanal secure, Zane arrived in New Caledonia, where she took on a new ensign named Herman Wouk. Wouk would serve on Zane for two years before transferring to Southard (DMS-10). By war’s end he was her executive officer. After the war, Wouk published books about the conflict, including The Caine Mutiny, a popular novel set on a fictional destroyer minesweeper, USS Caine (DMS-22). Woven into the story were some of his experiences aboard Zane.

With Wouk aboard, Zane’s next assignment was to support operations against the Russell Islands, northwest of Guadalcanal. The invading force consisted of the U.S. Army’s 43rd Infantry Division and the 3rd Marine Raider Battalion. Zane towed four landing craft loaded with men to the island, released them, and undertook minesweeping operations off the coast. Fortunately, the Japanese garrison had already evacuated, and there were no casualties to the Americans who landed.

In June, Zane was assigned to transport a company of the army’s 169th Infantry Regiment to participate in liberating New Georgia Island. Rain squalls and choppy waters caused the ship to ground as she was disembarking the troops. When Zane finally got her bow unstuck, she backed up and grounded the stern, damaging the all-important propellers. She was a sitting duck for four hours until she could be yanked free and towed back to Tulagi for temporary repairs.

More work was needed, so the veteran warship steamed under her own power back to Mare Island, California, for a comprehensive repair. She would return to Hawaii in September and serve there until January of 1944. She then took part in the invasion of the Marshall Islands and Kwajalein. On minesweeping operations near Eniwetok, she was slightly damaged again, this time due to mines exploding nearby. Another trip to port was required, and Zane reached Pearl Harbor for repairs.

Zane’s last campaign included minesweeping in support of the invasion of the Mariana Islands and Palau. Beginning in June, she set out warning buoys near minefields and fired on drifting mines with her guns. In July, she supported the landings on Guam as an anti-submarine escort ship. Following the success of those operations, Zane became a target-towing vessel, serving as such for the rest of the war. She was given a new designation as an auxiliary vessel, AG-109. The end of the war found her in the Philippines. She then returned to California for the a date with the scrap yard.

During the war, Zane earned six battle stars for her role in action from Pearl Harbor to the Marianas. She was also awarded the Navy Unit Commendation for her contributions to the victory at Guadalcanal. None of the World War I era destroyers remain in existence today.

Glenn Barnett has published more than 30 articles about World War II. He has worked in aerospace on the Apache Helicopter, B-1B bomber and several space craft programs.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments