By Peter Kross

On the evening of April 14, 1865, noted actor John Wilkes Booth entered Ford’s Theater in Washington, D.C., where a play entitled Our American Cousin was well underway. A number of people saw and recognized Booth as he entered the theater, but they paid him little mind. After all, Booth had performed often at the theater and he even got his mail delivered there since he had no permanent mailing address in the city.

Shortly after 10 o’clock, Booth entered President Abraham Lincoln’s private box overlooking the stage, barring the door behind him so that no one else could enter. He waited patiently until the proper time in the play arrived when he knew there would be the loudest laughter. “You sockdologizing old mantrap!” one of the cast called another. The audience roared. Stepping forward with his small pistol, Booth fired one bullet into the president’s brain, inflicting a mortal wound behind his left ear. He then leaped down onto the stage, catching his boot spur on the bunting beneath the presidential box and breaking his leg in the fall, but quickly limping offstage and making his way out of Washington on horseback with his accomplice, David Herold, a boyhood friend.

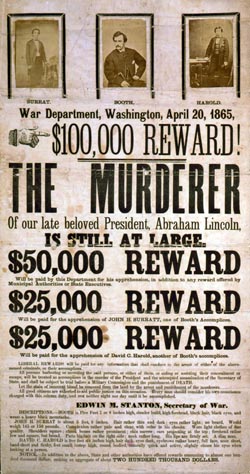

For the next 12 days, the largest manhunt in the nation’s history took place. Booth and Herold were finally cornered by Union soldiers at the Maryland farm of Richard Garrett, and after a brief firefight Herold gave up. Booth, remaining inside a burning barn on the property, was mortally wounded in the neck by a rifle shot and died on the morning of April 26. “Useless,” was the last word his Union captors heard him utter.

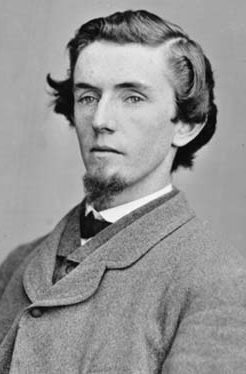

Booth’s death was not the end of the manhunt for his co-conspirators. While others in the plot were quickly rounded up, one man escaped, beginning the pursuit of the last Lincoln conspirator still on the loose. His name was John Harrison Surratt, Jr., and he was the son of Mary Surratt, at whose home the assassination had been planned. Before the hunt for John Surratt was over, his pursuers would follow him to Canada and Europe before finally catching up with him in Egypt.

Surratt In the Civil War

John Surratt was born on April 13, 1844, the last child of Mary and John Surratt, Sr. The elder Surratt was a drunk, but he managed to purchase a boarding house in Washington, as well as a tavern in Surrattsville, Maryland, where he also served as the local postmaster. As a young man, Surratt attended St. Charles College in Ellicott Mills near Baltimore. One of his Catholic seminary classmates there was Louis Wiechmann, who in later years would live in Mary Surratt’s boarding house at 541 H Street in Washington and would play an important role in the events leading up to the Lincoln assassination.

Shortly after the outbreak of the Civil War, Surratt left St. Charles School and joined the Confederate cause as a dispatch rider. He delivered mail from Washington to his Confederate allies across the Potomac River. He once told a friend, “If the Yankees knew what I was doing they would stretch this old neck of mine.” After the death of his father, Surratt came home to Surrattsville to take over the reins of the hotel. The tavern at Surrattsville was a weigh station for Confederate couriers who often stopped by for food and lodging. The store also served as a mail drop for Confederate riders, and Surratt became even more deeply involved in the Confederate cause.

The Conspiracy Begins

By the fall of 1864, Mary Surratt was having financial difficulty with her Surrattsville tavern; she decided to move her family to her boarding house in Washington. Mary leased the tavern to a man named John Lloyd for $600 a year. On December 23, 1864, Surratt and his friend Wiechmann were strolling down a street in Washington when they ran into Samuel Mudd, an old Maryland acquaintance who was Christmas shopping for his family. Accompanying Mudd was John Wilkes Booth. Mudd introduced Booth to Surratt, and they went to Booth’s room at the National Hotel. The actor took Mudd aside for a private conversation out of earshot of both Surratt and Wiechmann. He then handed Surratt a piece of paper and asked him to draw lines showing the roads leading into and out of Charles County. Shortly thereafter, the men all went their separate ways.

Over the next several weeks, Booth asked Surratt more questions about the routes from Washington to the Potomac River without telling him why he wanted such information. Exasperated, Surratt finally told Booth that he was fed up with his evasiveness and demanded to know what Booth wanted. Finally, Booth told Surratt of a plan he had been pursuing for some time—nothing less than a plot to kidnap President Lincoln. He planned to capture the president as he rode to the Soldiers’ Home and spirit him away to Richmond, where he would be exchanged for thousands of Confederate prisoners. Booth asked Surratt if he wanted to join the conspiracy. The young man said yes.

Booth became a frequent visitor to Mary Surratt’s boarding house on H Street. Booth and Surratt would sit alone for hours, poring over intricate plans to capture the president. Booth insisted that it was foolproof and that it could be carried out without a hitch. Booth’s plan called for the conspirators to take the captured president south via the Potomac River. They needed people who were familiar with the intricate routes and rivers to aid them. One such man was a German immigrant to the United States, George Atzerodt, a 29-year-old carriage builder who lived in Port Tobacco in Charles County. Surratt persuaded Atzerodt to join the conspiracy due to his vast knowledge of the Potomac and its tributaries. It was Surratt’s job to secure the boats to take Lincoln south; he bought one from Richard Smoot, a farmer who lived near Port Tobacco.

On April 14, the day of the assassination, Surratt was in Elmira, New York, on orders to scout the infamous Union prison there for a possible raid to free Confederate prisoners. It is not known if Surratt was privy to Booth’s plan to kill the president, but his being away from Washington on the day of the assassination proved beneficial to him in the long run. Booth had told Herold and Atzerodt that Surratt was in Washington, even though he knew that Surratt was in Elmira, possibly to set up Surratt as a fall guy if the assassination plot went awry.

Taking Flight in Canada

At 3 am on April 15, detectives from the Metropolitan Police arrived at the home of Mary Surratt. They had received a tip that her son may have been involved in the assassination, and they quickly followed up the lead. The police told boarders at the residence of the president’s assassination and said they were looking for Booth and Surratt. The detectives searched the house but found no trace of either man. The police then asked Mary Surratt when she had last seen Booth. She replied that she had seen him at 2 pm the previous day. They asked her if she knew the whereabouts of her son. Mary said no but that she believed he was in Canada. On April 17, detectives arrived once again at Mary Surratt’s boarding house and placed her under arrest for conspiracy in the assassination of the president.

While the manhunt for Booth and Herold was underway, John Surratt was back in Canada preparing for his journey to Europe. Unknown to most people in the conspiracy, Surratt had obtained a passport the previous January from both the American and British colonial officials in Quebec under the name of John Watson.

The United States government now mounted a worldwide hunt for Surratt. Confederate Secret Service agents took Surratt to a Catholic priest named Father Charles Boucher, who hid the former seminarian for three months at his parish in St. Liboire. Surratt was then given over to a Father La Pierre and stayed at his home for the next two months. In the meantime, Mary Surratt and the other Lincoln conspirators were tried, convicted, and hanged. Surratt made no attempt to contact his mother before her death. He said later, a little unconvincingly, that he was unaware of the grave danger she was in.

Believing that it was not safe to keep him in Canada any longer, the priests arranged for Surratt to be taken on board a ship, Peruvian, that sailed from Quebec to Liverpool, England. Surratt booked passage under the name “McCarthy.” Once the ship docked in Liverpool, Peruvian’s surgeon, Dr. Lewis McMillen, told the American vice-consul that Surratt was in the city.

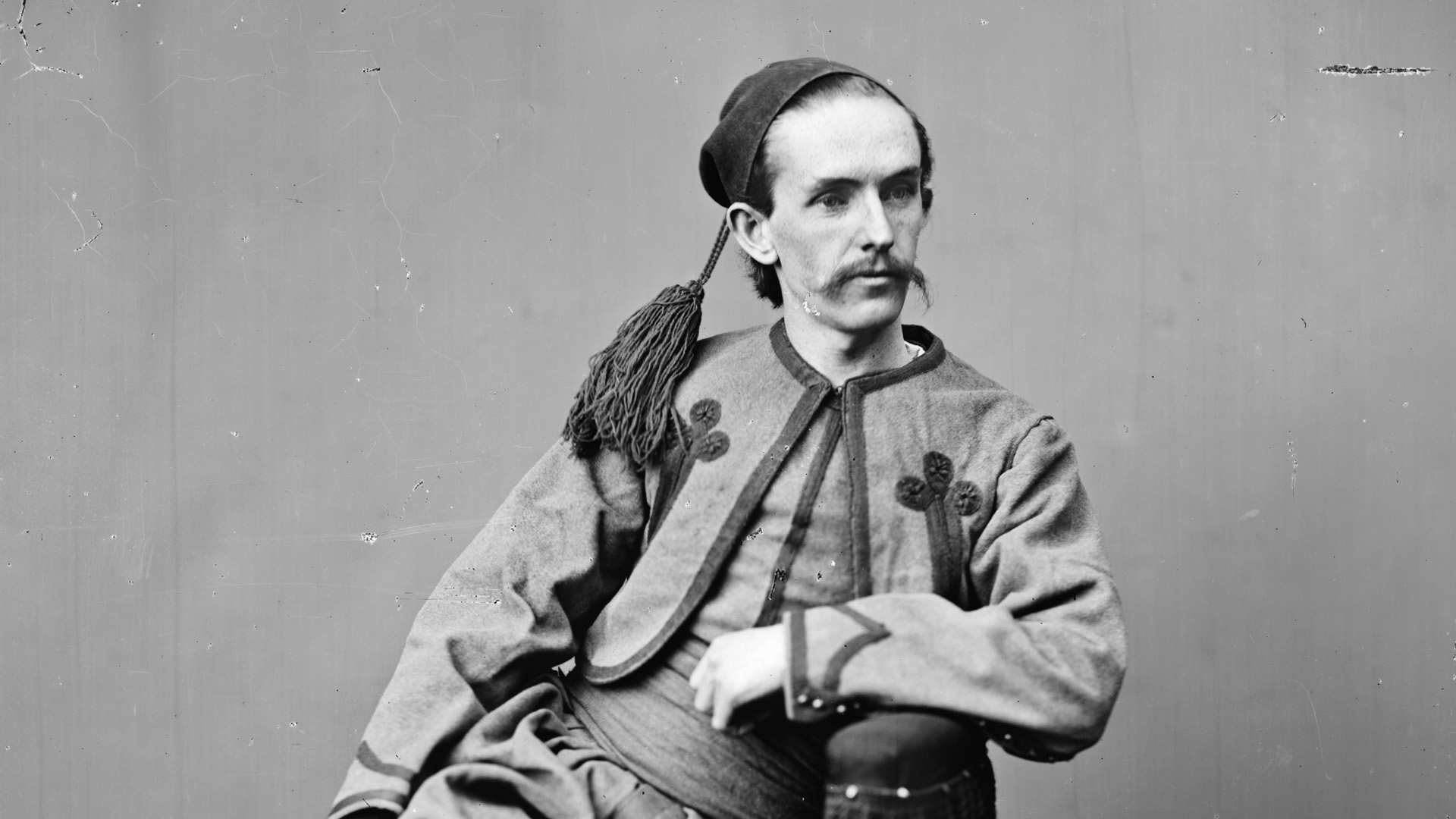

Surratt did not linger long in England. He soon made his way to Italy, where he enlisted in the Papal Zouaves under the name of John Watson. One of the men Surratt met in the same unit was a Canadian, Henri St. Marie, a Southern sympathizer who had joined the Confederate Army and been captured while serving on a gunboat. Surratt and St. Marie became friends, and Surratt told him that his real name was not John Watson, but John Surratt.

In the end, the trial resulted in a hung jury. A year later the government tried to bring new charges against Surratt, getting indictments based on the District of Columbia’s treason statute of 1862. The court ruled that the treason statute had expired two years previously and that Surratt was legally a free man. Had Surratt been tried in military court, it is highly probable that he would have been found guilty and executed, like his mother.

After the trial, Surratt moved to Rockville, Maryland, where he took a teaching job at a girl’s school. He then went on the lecture circuit, appearing first before an audience at the Montgomery County Courthouse, where he told his listeners that he had taken part in Booth’s attempt to kidnap the president but that he had no role or knowledge of the assassination. He married a woman in Baltimore in 1872 and found a job with the Old Bay Line shipping company as an auditor.

Surratt, the last of the Lincoln conspirators, died well into the 20th century, on April 16, 1916, almost exactly 51 years removed from the first presidential assassination. With his death, the last remaining figure in the assassination of the 16th president of the United States passed from the scene, unpunished and unrepentant.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments