By Joshua Sheperd

Although Union Colonel Silas Colgrove had previously led his men through some of the most horrific fighting in the eastern theater of the Civil War, the order he received on the morning of July 3, 1863, in the woods near Culp’s Hill at Gettysburg, was the most unnerving he had ever received. Dropping his head and looking noticeably disturbed, Colgrove pulled his nose, which he frequently did when pondering a difficult problem, and muttered, “It cannot be done; it cannot be done.” Then the colonel lifted his head and announced, “If it can be done, the 2nd Massachusetts and the 27th Indiana can do it.” His counterpart in the 2nd Massachusetts, Lt. Col. Charles Mudge, had a similar but even more ominous reaction. “Well, it’s murder,” said Mudge, “but it’s the order.” In the end, only one of them would be right.

A more curious pairing of outfits could not be found in the Army of the Potomac. The 27th Indiana had been Colgrove’s own regiment before his advancement to temporary brigade command. Recruited from the farm country of south-central and southern Indiana, the regiment was largely composed of homespun provincials who would have been considered commonplace had it not been for the efforts of Captain Peter Kop of Company F. “Big Pete,” as he was called, stood six feet, five inches tall and latched onto the novel plan of assembling an entire company of “stout and able bodied” men no shorter than 5 feet, 10 inches tall. Not only did he attain his goal, but a good third of his company stood over six feet tall. Topping them all was David Van Buskirk, a veritable Hoosier Goliath whose 6-foot, 11-inch, 300-pound stature earned him the title of tallest man in the Union Army. In fact, the giants of Company F drove up the regimental height average to such an extent that the 27th claimed the distinction of being the tallest regiment in Federal service.

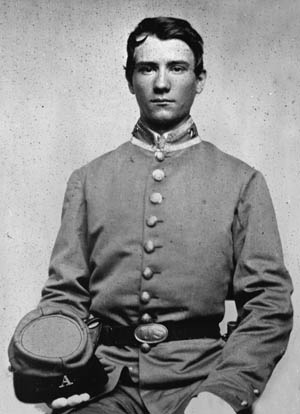

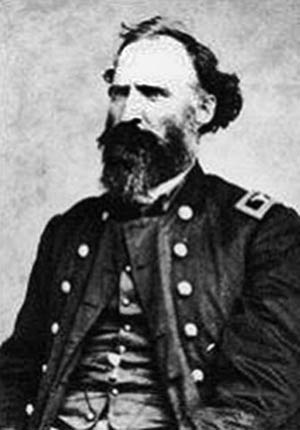

Despite their imposing stature, the robust farm boys of the 27th were in desperate need of real training and they received it from Colgrove. Born in Steuben County, New York, on May 24, 1816, Colgrove immigrated to the backwater of Winchester, Indiana, in 1837 and opened a law practice two years later. Foul-mouthed and ill-mannered, Colgrove quickly exhibited a distinct talent for annoying his neighbors. The same year he was admitted to the bar, he busied himself fighting Southern slave hunters in the Randolph County courts, as well as litigating on behalf of the free black settlement of Cabin Creek. The resulting ire of the Democratic community little affected the prickly Colgrove, who seemed to relish the fuss, even after he was violently accosted by a gray-haired matron. “I never got such a tongue-lashing in my life,” an amused Colgrove recalled.

A state legislator at the outbreak of the war, Colgrove was commissioned lieutenant colonel of the 8th Indiana and served a three-month stint in western Virginia, including action at the Battle of Rich Mountain. Governor Oliver P. Morton, always on the lookout for officers with ties to the state’s Republican machinery, rewarded Colgrove with the colonelcy of the newly formed 27th in September 1861.

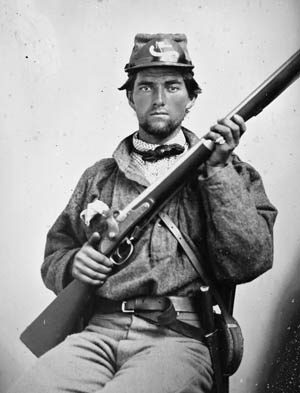

Meanwhile in Boston, another volunteer regiment, the 2nd Massachusetts, was composed of far different makings than its Indiana counterpart. The officer corps of the 2nd Massachusetts was largely composed of young men from some of the wealthiest and most privileged families in the Bay State. Indicative of the lot was Charles Redington Mudge, a recent graduate of Harvard University. Mudge received news of the outbreak of war while still in bed on a Sunday morning. He recalled in a letter to a friend, “I jumped out of bed at the news of the capture of Fort Sumter, and fully made up my mind to fight; and when I say fight I mean win or die.”

Born in New York City on October 22, 1839, Mudge enjoyed a comfortable upbringing; his father, Enoch Mudge, was one of the wealthiest cotton and wool traders in the nation. The younger Mudge was a cheerful, popular individual. He enrolled in Harvard in 1856 and quickly revealed a marked indifference to his studies. The president of Harvard was obliged to forward a cautionary letter to Mudge’s father, warning him that Charles’ work was “imperfectly performed, and he has persisted in disregarding the rules of order in the college. I trust he will now let the responsibilities and duties of life sober him down, and cure that levity of conduct which has been so particularly displayed by his residence in College.”

Mudge was far more interested in sports and a thriving social life. Lithe, muscular, and athletic, he distinguished himself in manly sports and exercises, including rowing, boxing, and gymnastics. An excellent vocalist as well, he served as vice president of the prestigious Hasty Pudding Club. Mudge’s personable demeanor garnered him the near universal affection of the student body. “This popularity was founded upon a remarkable unvarying kindliness of nature,” thought one acquaintance. “An instinct assured each classmate that there could be no chance of a word of harshness or sarcasm from him.”

Mudge’s personality, however, won few academic points from the faculty. In July 1860, his father was informed that Charles’ degree “will be probably granted in a year if nothing occurs in the meantime to make it impossible.” The coming of the Civil War sent Mudge scrambling to secure his son’s degree. After Charles was commissioned a lieutenant in the 2nd Massachusetts, the elder Mudge pleaded his son’s case to the president of Harvard. “As my son may never return and might leave immediately,” he wrote, “I have to ask if he can now receive his degree, the reasons will doubtless be sufficiently apparent to the Faculty.” The endeavors of Mudge’s influential father were successful. By the time the 2nd Massachusetts headed for the front in July 1861, Charles Mudge had been granted his degree.

The regiment was arguably the best-drilled volunteer regiment in Federal service. Its commander, George H. Gordon, was a fussy West Pointer who instilled a professional bearing in his regiment. The Massachusetts men soon earned the nickname of “Gordon’s Regulars.” The men of Company F were particularly pleased with Mudge. “It was his nature,” recalled one acquaintance,” to appreciate the good traits of everyone.”

Unfortunately for the men of the 27th Indiana, the same could not be said for Silas Colgrove. From the outset, the colonel proved decidedly unpopular with most of his men and virtually all of his officers. A sullen and foreboding man, “Old Coley” demanded both rigorous drill and rigid discipline. Not surprisingly, his unbending personality and explosive behavior alienated his troops, all fresh volunteers unaccustomed to taking orders. The soldiers generally felt his overbearing style bordered on the tyrannical, and it was not uncommon for a wayward soldier to be rebuked with a blistering haze of profanity.

Barely a month and a half after mustering in, a cabal of disaffected officers forwarded a letter to Governor Morton requesting a new colonel for the 27th. The insubordinate letter was shelved out of hand, but the malcontents then confronted Colgrove directly and pressed for his resignation. Normally combative, Colgrove was stunned by the lack of confidence. “It was a heavy stroke and took the colonel completely by surprise,” remembered one observer. “Instead of getting in a rage as all expected he would it humbled him right down.” A flustered Colgrove told his officers that he preferred losing his life to resigning and going home in disgrace.

Undeterred, the group sent another letter to the governor requesting Colgrove’s immediate recall. “We have patiently submitted to insults,” the letter read, “until forbearance is beyond endurance. The regiment is now on the point of demoralization for such causes as having officers called fools, liars & threatened with a knockdown.”

Far from effecting Colgrove’s recall, the letter backfired for its signatories. Commissary Sergeant Simpson Hamrick, a casual observer of the tempest among the officers, noted that “Colgrove will be too fast for them, for he is shrewd and smarter than all the officers combined. They will drop one by one, and the regiment will still be controlled by the one man power.” True to Hamrick’s prediction, Colgrove retained not only the governor’s confidence but his commission as well and succeeded in outlasting his opponents. Over the course of the following year, all the insubordinate officers either resigned or were transferred out of the 27th, replaced with men who were either loyal to Colgrove or smart enough to keep their own counsel. Hamrick summed up the imbroglio in a letter home. “The great trouble is our officers,” he wrote. “Colgrove is decidedly the best, but has an abuseful disposition. But with all his vices he is the officer worth a notice.” There was no doubt, he said, about Colgrove’s “fighting pluck.”

Such infighting was only aggravated when, in March 1862, the 27th Indiana, 2nd Massachusetts, and 3rd Wisconsin Regiments were brigaded together in Maj. Gen. Nathaniel P. Banks’ V Corps. The rough mannerisms of the Hoosiers clashed with the prim carriage of Gordon’s Regulars, and a mutual animosity developed. Promoted to brigade command, Gordon was regarded as a pretentious martinet who held his “seven-foot Indiana volunteers” in little esteem. The Hoosiers responded with equal contempt for the “Lilliputian” Bay Staters. Derided for their pronounced Hoosier drawl, Colgrove’s men were likewise displeased with their connection to “one of the most detestable Yankee brigades.” One Hoosier summed up his comrades’ feelings in a letter home, bemoaning that “one glance is sufficient to distinguish the ‘semi-barbarous’ 27th & their Badger friend the 3rd Wisconsin, who are pretty much in the same category, from their polished bandbox neighbors.”

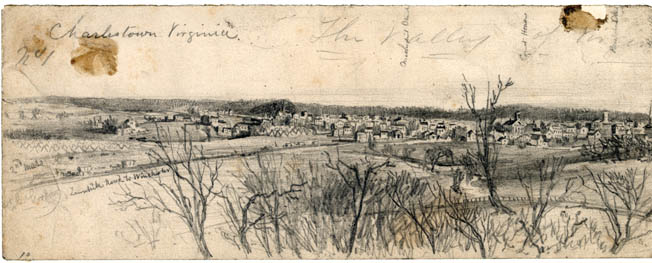

Such harmless banter could be expected from soldiers, but the antipathy that developed between Gordon and the 27th subsequent to their first engagement was less amusing. Banks’ V Corps, including Gordon’s brigade, was soundly trounced by Maj. Gen. Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson’s Valley Army at Winchester, Virginia, on May 25, 1862. During the chaotic retreat from town, a good number of men from both regiments were taken prisoner. Company F of the 2nd served as a rear guard, and Mudge, hobbled by a painful wound to the leg, was narrowly saved from capture by the efforts of friend and former classmate Lieutenant Robert Gould Shaw.

Humiliated by the debacle, Gordon cast about for a scapegoat and roundly criticized the performance of Colgrove’s rustics. Labeling them “that incorrigible 27th Indiana,” Gordon wrote that the Hoosiers were “naturally insubordinate and cowardly.” Although Colgrove was well disposed to dressing down his own men, he bristled at such language from Gordon and averred that there was “more good fighting material in the 27th than any regiment in the service.”

The opportunity for both the 27th Indiana and the 2nd Massachusetts to prove their mettle came during the Maryland Campaign of 1862. Banks’ command was redesignated the Army of the Potomac’s XII Corps, of which both regiments helped form the 1st Division’s 3rd Brigade. On the morning of September 13, the 27th, at the head of XII Corps, was probing for the Army of Northern Virginia when the men were ordered to halt in a hay field south of Frederick. First Sergeant John M. Bloss and Corporal Barton W. Mitchell were resting in the clover when they discovered a discarded letter lying close by. It turned out to be one of the most fortuitous finds in military history.

Upon further inspection, Bloss discovered that the letter was not only wrapped around three fine cigars, but was headlined “Confidential Special Orders No. 191 Hdqrs., Army of Northern Virginia.” The two Hoosier volunteers had unwittingly discovered both the plans and detailed troop dispositions of the Rebel army. Bloss immediately recognized its importance and reported the find to Captain Kop, who directed it to Colgrove. Colgrove personally delivered the order to XII Corps headquarters, and by noon it was in the hands of Maj. Gen. George McClellan.

The discovery made by two of Colgrove’s farm boys helped bring about General Robert E. Lee’s desperate delaying action at South Mountain on September 14 and the Battle of Antietam three days later. Although Gordon’s brigade had seen action in the Shenandoah and at Cedar Mountain, it was the unparalleled carnage of Antietam that truly blooded the men. The brigade took part in XII Corps’ grand assault on Lee’s left and entered the horrific fight for David Miller’s cornfield. Mudge suffered bruised ribs and Colgrove had his horse shot from under him, but the rank and file paid a truly grim price. In the 27th Indiana alone, of the 443 men taken into action 36 were killed and a staggering 235 were wounded.

Subsequent to the bloodbath at Antietam the rancor between the two regiments subsided, and their petty squabbles dissipated. Eventually even Gordon praised the conduct of the “incorrigible” 27th, one of whose members proudly wrote home, “Even our old Yankee general said we was the best fighting material he ever saw.”

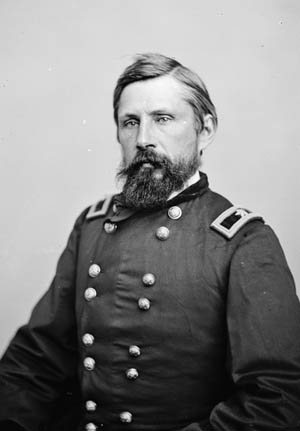

In the autumn of 1862, command of the brigade passed from Gordon to Thomas H. Ruger, formerly the colonel of the 3rd Wisconsin. An attorney in civilian life, Ruger was nevertheless a professionally trained soldier. He had attended West Point and graduated third in the class of 1854, then served in the exclusive Corps of Engineers. Inter-regimental relations proved smoother under Ruger’s firm but even-tempered leadership. “We regarded him as a strict disciplinarian,” said one of his men, “but he was a just man, humane.”

Unit cohesion would be sorely needed during the following spring’s campaign. By that time the Army of the Potomac had a new commander in the person of Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker. Determined to finally bring Lee to bay, “Fighting Joe” launched a surprise offensive in April 1863, and the affair initially went well. The 27th Indiana was tasked with securing Germanna Ford, a vital crossing of Virginia’s Rapidan River, and by the first of May the two armies were arrayed for battle in dense forest near the Chancellorsville crossroads. Stonewall Jackson’s unexpected flank attack of May 2 caught Hooker entirely by surprise, and the Confederate juggernaut wrecked one Federal brigade after another. As darkness fell, Jackson ran into stiffening Federal resistance, and following his accidental wounding the attack was halted for the night.

Among XII Corps troops in line that night was the 1st Division’s 3rd Brigade, including Colgrove’s 27th Indiana and the 2nd Massachusetts under Colonel William Cogswell. Realizing that the Confederates would press their advantage in the morning, Colgrove braced his men for the coming battle, nabbed two fieldpieces from a passing battery, and admonished his troops to form into line and stand firm.

When the battle renewed at dawn the next day, Ruger’s brigade was assailed by regiment after regiment of fresh troops, and the fighting intensified, in the words of one participant, to a struggle “which for cool, deliberate action and resolute, unflinching endurance, on both sides, has had few parallels.” Colgrove, stripped down to his shirt, was busy helping his volunteer gunners. He called out to his 19-year-old son, Theodore, the regimental major, “Here, boy, you run the regiment while I run this here gun.”

As the Rebel line faltered and gave way, the 27th Indiana, along with the 2nd Massachusetts and 3rd Wisconsin, mounted a vigorous bayonet charge that swept their front. The 2nd engaged in a brutal hand-to-hand encounter with the 1st North Carolina, and Mudge later recorded that he had prayed for courage, “but I never believed a man could feel so joyous, and such a total absence of fear, as I had there.”

Colgrove received a nasty wound to the hip, but the ball missed any bone. Cogswell was not as fortunate, receiving a serious wound that incapacitated him. Command of the 2nd fell to Mudge, a major since the previous November, who wrote to his father after Chancellorsville that the pressures of battle and command weighed heavily on him, “yet I had courage enough, by God’s help, to bear it all coolly.”

Mudge’s repeated allusions to divine assistance highlighted his reawakened interest in spiritual concerns. By upbringing an Episcopalian, Mudge apparently underwent something of a personal revival consequent to his experiences in the war. Whereas the crusty Colgrove, described by one of his men as the “most profane man I ever came in contact with,” was entirely indifferent to the administration of divine services to his men, Mudge took it upon himself to personally perform such duties in the absence of a chaplain. He was known to keep an Episcopal prayer book in his pocket, and his attention to the spiritual welfare of the regiment further endeared him to the men.

Ruger’s brigade would face its most desperate fight of the war two months later. Flushed with the success of its Chancellorsville victory, the Army of Northern Virginia again crossed the Potomac River in the middle of June and ushered in the campaign that would culminate at the crossroads of Gettysburg. Hooker shadowed the Rebel army, but his days of command were numbered. Exasperated by the disastrous drubbing of the Army of the Potomac, the Lincoln administration was determined not to risk another such defeat on northern soil and pressured Hooker into resigning. His replacement was V Corps commander Maj. Gen. George G. Meade, awakened from a dead sleep and given command of the army in the early morning hours of June 28.

Three days later Meade was drawn into the epic struggle at Gettysburg, and the orders he issued on July 1 would have fatal repercussions for the men of the 27th Indiana and 2nd Massachusetts. Known as the Pipe Creek Circular, the directive detailed Meade’s strategic vision for the campaign and resulted in a gross misunderstanding for one of his corps commanders. In the circular, Meade made provision for a possible withdrawal of his army to Pipe Creek in Maryland. In the event such a move would become necessary, he appointed XII Corps commander Maj. Gen. Henry Slocum as commander of the army’s right wing. This nebulous unit was to consist of both Slocum’s XII Corps and V Corps. In assuming command of the right wing, Slocum left a vacancy in the command of XII Corps, which was filled by Brig. Gen. Alpheus Williams of the 1st Division. Williams was then replaced by Ruger. Command of Ruger’s 3rd Brigade, consisting of the 27th Indiana, 2nd Massachusetts, 3rd Wisconsin, 13th New Jersey, and 107th New York, fell to the brigade’s senior colonel, Colgrove, who was still recuperating from his Chancellorsville wound. Lt. Col. John Roush Fesler assumed command of the 27th.

Throughout the three days of fighting at Gettysburg, Slocum labored under the deluded impression that he commanded the so-called right wing, an arrangement that Meade’s headquarters remained seemingly unaware of, as well as the new chain of command in XII Corps. This unexpected shakeup of senior officers in the middle of an active campaign led to a most ungainly and unfortunate command structure at the worst possible time.

Colgrove’s brigade arrived at Gettysburg on the afternoon of July 1 and initially deployed for action in front of Benner’s Hill. The brigade pressed forward, near the crest, but was quickly called back. News arrived of the collapse of I and XI Corps, and Williams ordered a withdrawal of his own troops to a safer position south of Wolf Hill near the Baltimore Pike.

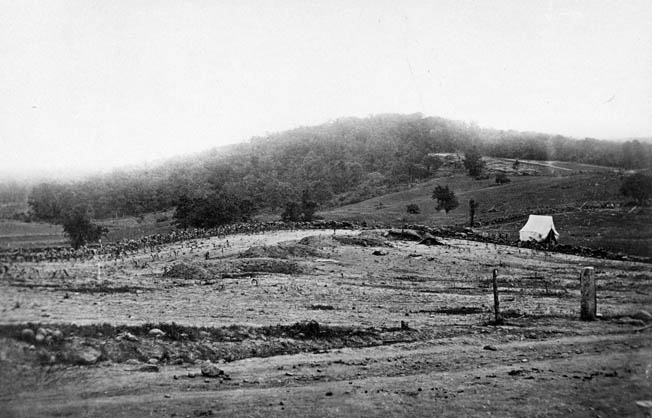

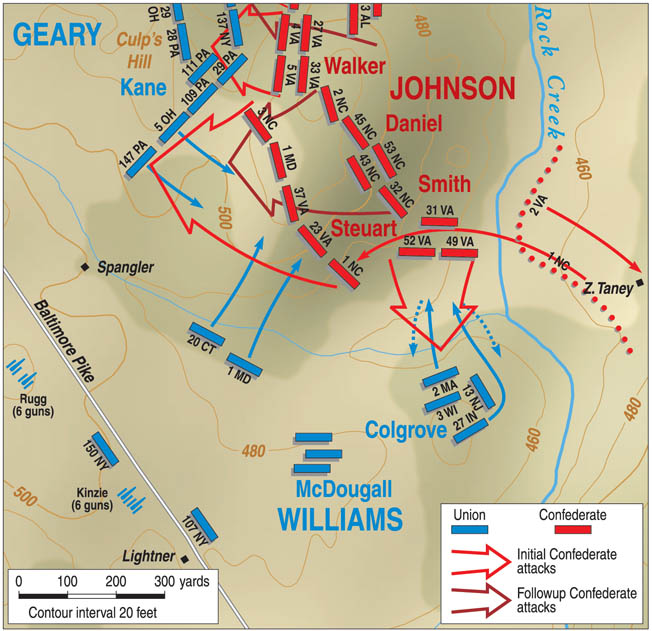

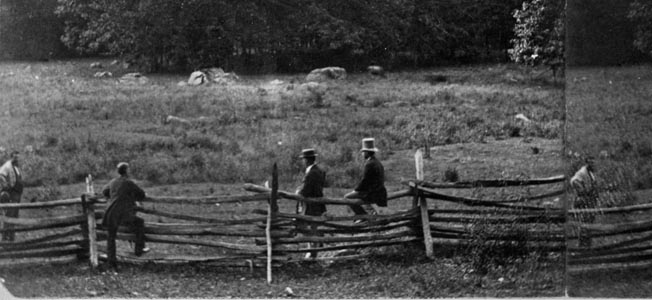

The following morning, Colgrove’s most reliable regiments—the 27th Indiana, 2nd Massachusetts, and 3rd Wisconsin—engaged in a hot skirmish with the enemy on Wolf Hill before the entire XII Corps took up positions on Culp’s Hill, tying into the right of I Corps. Slocum’s men immediately set to work erecting breastworks and soon constructed a stout line of entrenchments from the crest of upper Culp’s Hill down across the lower hill and ending near Spangler’s Meadow. The meadow, largely surrounded by forest and about 100 yards wide, was a low-lying, boulder-strewn, boggy area. In the center of the meadow bubbled Spangler’s Spring, a popular picnic site for the locals, and the spring fed into a small rivulet that flowed east into Rock Creek.

From their position on Culp’s Hill, the troops could hear the roar of battle raised by the grand Confederate assault that was unleashed against Meade’s left during the late afternoon. As the Rebel attack rolled north along Cemetery Ridge, Meade ordered the withdrawal of XII Corps from Culp’s Hill to bolster his weakened left. Following a mild protest from Slocum, Meade allowed just one brigade of the corps to remain behind and guard the summit of the upper hill. For the men of Colgrove’s brigade, the maneuver proved anticlimactic. The men formed and advanced into Weikert’s Woods but just as quickly were ordered back to their former position. The Confederate assault on the left had run out of momentum, but a new threat had emerged on the right.

The Confederate division of Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson assaulted the Federal works on Culp’s Hill, and although Johnson’s men were unsuccessful in seizing the stubbornly defended summit, they quickly occupied the empty trenches of XII Corps on the lower hill. As dusk fell, Colgrove found McAllister’s Woods clear of Confederates, and he sent Company F of the 2nd Massachusetts across Spangler’s Meadow to probe the lower hill. The Bay Staters captured a Rebel officer and 22 soldiers who appeared to be straggling about looking for water. Mudge reported that the works on the lower hill had been captured and occupied by forces from Brig. Gen. George Steuart’s brigade, but Colgrove and Ruger wanted further proof.

Mudge led his entire regiment to the north edge of the meadow and ordered Captain Thomas B. Fox’s Company K farther up the hill. Two skirmishers from Company K finally confirmed the presence, in force, of Confederate troops. The two men fell in with a group of soldiers from the 23rd Virginia and, after an uneasy exchange, the Virginians exclaimed, “Why, they are Yanks!” One soldier was immediately captured, the other sprinted back down the hill. While Mudge withdrew the bulk of the regiment to McAllister’s Woods, Fox made a bold showing and called out to the Confederates to surrender. The outnumbered Federals were met with an eruption of musketry that lit up the hillside, and Company K was likewise withdrawn.

Members of the 27th Indiana stood a respectable distance away and listened to an impromptu meeting of senior officers inside McAllister’s Woods. Colgrove argued for an immediate attack to recapture the works; Ruger demurred, noting that the gathering darkness would compound the difficulty of carrying the works, which were occupied by an unknown number of Confederates. Williams believed that his men should sit tight until daybreak when “we will shell hell out of them.”

When informed that much of XII Corps’ breastworks had been occupied by the enemy, Slocum responded, “Well, drive them out at daylight,” an order that Williams felt was “more easily made than executed.” As acting corps commander, it fell to Williams to develop a tactical plan for the following morning. The general ultimately decided to make the main thrust with his left wing. Ruger’s 1st Division, which occupied the right, would hold a “threatening position” but only push the Rebels “should opportunity offer.” Williams judged the Confederate left flank opposite Colgrove’s brigade “quite impregnable for assault.”

At daybreak, Williams unleashed his hellish barrage, and when the firing ceased, Johnson launched an ill-fated assault on Culp’s Hill. Meanwhile, Colgrove’s men were subject to a nagging fire from Confederate skirmishers. To the north of Spangler’s Meadow, six companies of the 1st North Carolina were scattered among an outcropping of boulders near the base of the lower hill. To their left, the 2nd Virginia was positioned behind a stone wall that ran perpendicular to the captured breastworks. Across Rock Creek, the remaining four companies of the 1st North Carolina were concealed on the hillside and in the farm buildings of Zebulon Taney and, in the words of one Federal, “annoyed us terribly by their skillful marksmanship.”

At 7 am, matters were made worse for the Federals when the Confederate position was reinforced by the Virginia brigade of Brig. Gen. William “Extra Billy” Smith. A professional politician, Smith was a former member of the Confederate Congress and since May 1863 had been the governor-elect of Virginia. He was also a tough fighter, thrice wounded in action, and respected by his men. Smith personally led his soldiers down the hill to the stone wall, where they relieved the troops already on the scene. The six 1st North Carolina companies retired from Spangler’s Meadow; Colonel John Nadenbusch led his 2nd Virginia across Rock Creek to a position where they could readily enfilade any Federal thrust across the meadow. Nadenbusch, a miller from Berkeley County, had received his appointment to the colonelcy in March, but both he and his regiment were experienced veterans. A contingent regiment of the famed Stonewall Brigade, the troops had seen action from the war’s outset.

Subsequent to Johnson’s unsuccessful assault on Culp’s Hill, Slocum was convinced that the Rebels were “becoming shaky” and deemed a counterattack in order. Bypassing Williams, Slocum ordered Ruger to assault the captured works with two of his regiments. The cautious Ruger requested that a reconnaissance be carried out first to ascertain the actual strength of the enemy on the lower hill. Slocum assented, and Ruger passed on verbal orders to a staff officer, Lieutenant William M. Snow. Colgrove was “to try the enemy with two regiments, and if practicable, to force him out.” Snow was dispatched around 10 am.

The subsequent conversation between Snow and Colgrove remains a mystery. Snow maintained that he delivered the verbal orders exactly as they had been given by Ruger, but Colgrove left the discussion with Snow with an entirely different impression. He claimed to have been ordered to “advance your line immediately” and that he was given no discretion. Colgrove was further under the deluded impression that the division’s 1st Brigade had mounted a successful counterattack to his left and was in need of support. Because of the narrow front that Spangler’s Meadow afforded, Colgrove could only deploy two of his regiments. He likewise realized that throwing forward a skirmish line into the open expanse of the meadow would amount to little more than a death sentence for the troops.

Colgrove concluded that to comply with Ruger’s orders he was forced to storm the lower hill with two of his regiments, and the selection of the two regiments was an unenviable dilemma that caused Colgrove to nervously tug at his nose and mutter to himself. At his immediate disposal were the 3rd Wisconsin on the left, the 2nd Massachusetts directly facing the meadow, the 13th New Jersey fronting Rock Creek, and the 27th Indiana somewhere to the rear of the Massachusetts men. The colonel considered his core regiments—the Hoosiers, Badgers, and Bay Staters—to be the “three best regiments I have ever seen in action.” Ultimately, he settled on the 2nd and the 27th and dispatched a messenger accordingly.

When the courier reached the 2nd Massachusetts he found Mudge and his adjutant, Lieutenant John A. Fox, and delivered the order to attack. Mudge was nonplussed. He asked the courier if he was certain that was the order and was assured that it was. “Well,” said Mudge, a little dryly, “it’s murder but it’s the order.”

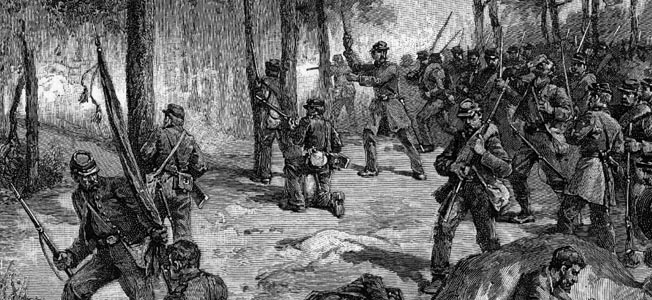

Disaster unfolded in minutes. Already in position to launch the attack, Mudge ordered his men forward at the double quick. As soon as the regiment emerged into the meadow, it was met with a hail of musketry. Captain Thomas Robeson of Company E collapsed with a mortal wound, as did Color Sergeant Levitt C. Durgin. Corporal Rupert J. Sadler then grabbed the flag and was shot dead in seconds. The next color-bearer, Corporal James Hobbs, went down wounded, to be relieved by Private Stephen A. Cody, who saved the colors from touching the ground.

The regiment steadily advanced, drove in a handful of Confederate skirmishers, but saw its own men shot down by the dozen. The grim spectacle awed onlookers in the 3rd Wisconsin, who remained behind but were prepared to move up in support. To cheers of “See there goes the 2nd,”the Badgers stood helpless as the Massachusetts men were cut down like grass in a prairie fire.

Off to the right, the 27th Indiana arrived late to the fight. From its apparent position facing Rock Creek, the regiment was forced to change front at the double quick and face the meadow. In the frenetic confusion of the moment, Fesler’s men unceremoniously ran into the ranks of the 13th New Jersey. Colgrove barked orders to unsnarl the lines and with shrill, piercing tones called out to his Hoosiers, “Twenty-seventh, charge! Charge those works in your front!”

The regiment cheered, charged out from McAllister’s Woods, and was met with, in the words of Colgrove, “One of the most destructive fires I have ever witnessed.” The regiment veered to the right of the Massachusetts men and, when halfway across the meadow, was staggered by “a terrific volley, one of those well-aimed, well-timed volleys which break up and retard a line, in spite of itself.” So many men fell that survivors described the earth simply swallowing up the regiment. Fesler’s right flank, entirely exposed and subject to an enfilading fire from the Confederates across Rock Creek, suffered especially heavy casualties. Theodore Colgrove, urging the men from horseback, thought that the three flank companies had been brought down en masse.

The regiment stalled amid the hail of gunfire and exchanged volleys with the Confederates. “The air was alive with singing, hissing, and zipping bullets,” noted one survivor. The color guard was virtually annihilated; one of its survivors, Color Sergeant John L. Files, pressed on through the gauntlet despite the loss of his comrades. The flag was then seized by Lieutenant William W. Dougherty, who attempted to rally the men for a further push. Subject to such a scathing fire, the men could not be budged; Dougherty drove the flagstaff into the ground.

In the ranks of the 49th Virginia of Smith’s brigade, Private William Johnson took aim at a conspicuous Federal officer mounted on a black horse—possibly Major Colgrove—who was carrying a flag and urging on his men. Johnson misfired, recapped the nipple, and misfired again, finally noticing that his hammer was blocked by a small chain. Rectifying the problem, Johnson was about to pull the trigger when his own rifle was hit by a ball, which mangled his left hand and struck him in the chest.

At the head of the 2nd Virginia, Nadenbusch was busy waging a welcome one-sided fight. While suffering scant casualties of his own, Nadenbusch’s heated oblique fire was tearing great gaps in the ranks of the Hoosiers in the meadow. He later recorded that “with this concentrated fire the enemy was soon forced to retire in confusion.” Meanwhile, from his vantage point in McAllister’s Woods, Colgrove appraised the futility of leaving his men in the open and sent word to Fesler to pull the men out. Dougherty was removing the flag when Private Alonzo Burger offered to take it, and the regiment proceeded to effect the retreat rapidly but in good order.

For the men of the 2nd Massachusetts, the nightmarish ordeal was not quite over. The regiment had advanced to within yards of the Confederate works and found some cover amidst the outcropping of boulders. Mudge, who had gone into action with the color company, was shot through the neck and killed instantly. Command fell to Major Charles F. Morse, who noted that his men grappled with the Confederates “at the shortest range I have ever seen two lines engaged at.”

Men were dropping on every side in the toe-to-toe fight, but the Massachusetts men were inflicting few casualties on the well-concealed Confederates. Still carrying the flag, Private Cody mounted a large boulder, waved it at the enemy, and was quickly shot dead. Another fellow who raised the flag went down wounded. While enemy fire poured in from the front, a small detachment of Rebels darted from their works in an attempt to turn the regiment’s right.

Little inclined to further expose his men to such pointless slaughter, Morse ordered a withdrawal. Before heading out, one of the men thought to remove the ever-present Episcopal prayer book from Mudge’s pocket. Morse then led his men to the left of their former position and formed behind a stone wall. “I never saw a finer sight,” thought one observer, “than to see that regiment, coming back over that terrible meadow, face about and form in line as steady as if on parade.”

Ever impetuous, “Extra Billy” Smith ordered the 49th Virginia, backed up by the 52nd, into the meadow. The ill-conceived counterthrust was quickly driven off, and Morse finally received an order from Colgrove to return the 2nd to its former position. As the smoke settled, the tragic cost of the bungled charge became all too obvious. A full third of the 27th Indiana had been hit—18 killed, 93 wounded. The 2nd had suffered slightly higher casualties of 22 killed, 112 wounded. To Morse, “it was a sad thing calling the rolls.”

Attempting to explain the disaster in his official report, Alpheus Williams wrote that Colgrove either “misapprehended the orders sent him or they were incorrectly communicated.” Colgrove maintained that when he received his orders, Snow said, “The general directs you to advance your line immediately.” Snow was equally adamant that a general attack was to be mounted only if the Rebels were “not found in too great force.” Snow said he “could never quite understand” why the charge was ordered. Continuing to hash out the matter was pointless. Ruger ultimately came to the conclusion that it was impossible to ascertain which man was responsible for the mistake. His final estimation of the incident was that it was “one of those unfortunate occurrences that will happen in the excitement of battle.”

Veterans of the 2nd Massachusetts recalled the disaster that befell their regiment at Culp’s Hill with surprising equanimity. “Where the mistake was made I never knew and don’t care to know,” recorded Lieutenant Fox. “We never had any hard feeling toward Gen. Colgrove. He sent his own Regt. in with us, and they stood as long as brave men could be expected to.” That was cold comfort for Charles Mudge, who had foreseen all too clearly that his orders that morning were, indeed, “murder”—his own included.

My Great Grandfather, John G. Wallace was a member of the 27th Indiana and was wounded during this charge on July 3, 1863. The article is a thrilling expose’ of the events of that day. Thank you so very much.