By Terry Gore

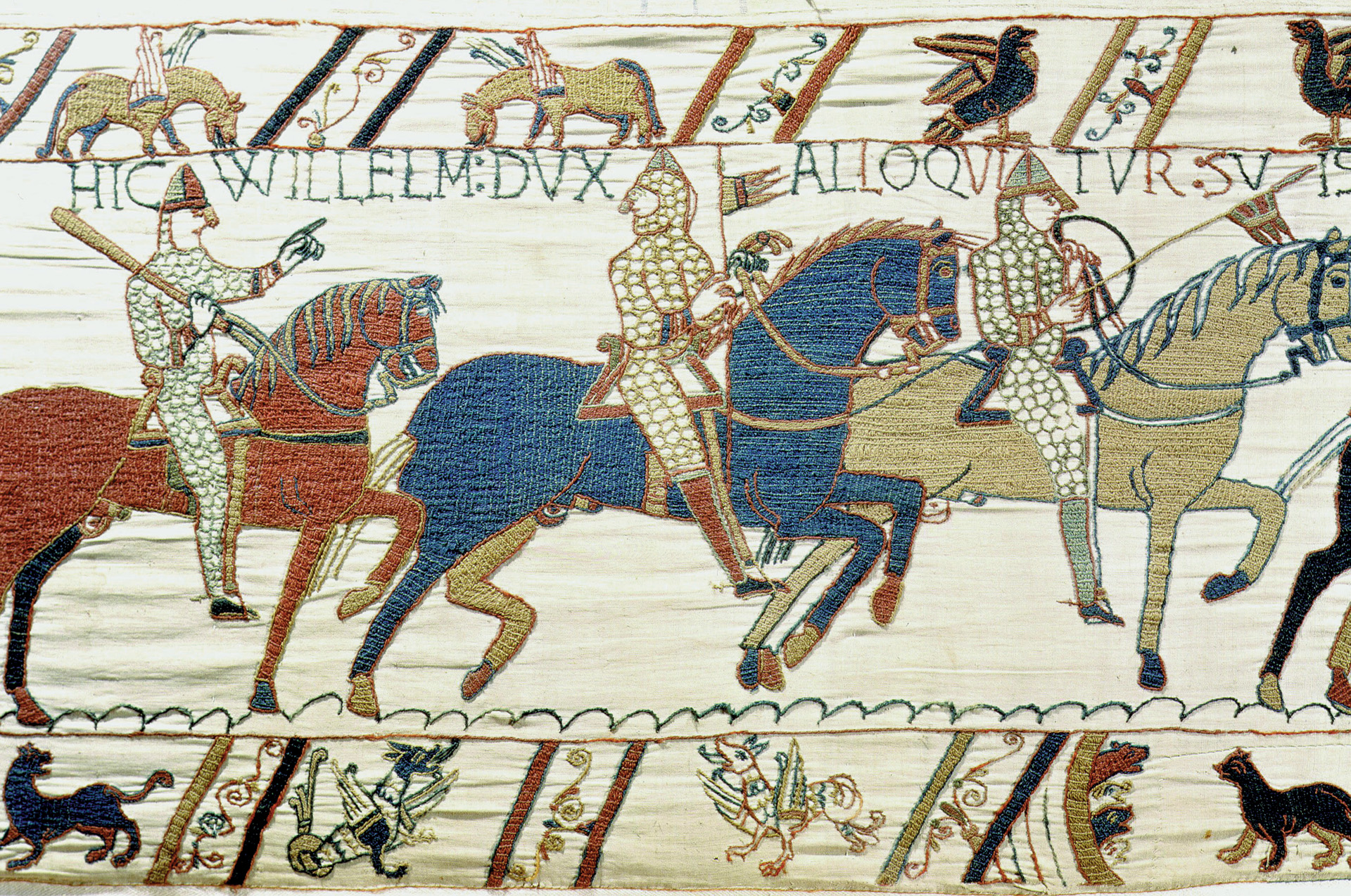

Italy in the mid-11th century was in chaos. Ostensibly held together under the auspices of papal and Holy Roman Empire authority, the peninsula had become a collection of feuding city-states, each under its own local ruler or warlord. With a population estimated at less than 5.5 million inhabitants, the former home of the vast Roman Empire of the Caesars was far from its old Imperial glory.

For almost 500 years, most of the local rulers had been semi-independent Lombard princes. The Lombards had first appeared in Italy as allies of the Byzantine Empire, fighting alongside Imperial armies during the attempted reconquest of Italy in the 6th century. In the latter half of that century, the Lombards had invaded Italy en masse, attacking and defeating their former allies and restricting the Byzantines to a few coastal cities. The independent Lombard princes retained power in their various areas of influence, warring upon each other when the mood struck.

Added to this mix were the ubiquitous Byzantines, eager to maintain and expand their foothold in the remaining areas of their once strong presence in Italy. They continued to claim southern Italy as their own, fighting a number of battles against the Lombards and their Norman allies over the first decades of the 11th century.

Also not to be ignored were the Muslims who controlled Sicily, a short distance from the Italian peninsula. Their raids up and down the Italian coast did little to encourage feelings of security for the inhabitants near the sea.

As if this situation were not volatile enough, another faction had been thrown into the equation. Norman adventurers had begun to infiltrate into Italy as early as the first quarter of the 11th century, first serving as mercenary fighters in the armies of both the factional Lombard princes and the Byzantines. Leo of Ostia made note of their arrival when he wrote, “There came to Capua about 40 Normans. These had fled from the anger of the Count of Normandy and they were … with many of their followers moving about the countryside in the hope they might find someone who would be ready to employ them.”

Not content to simply be landless warriors, the more enterprising of the Norman lords settled onto lands they had “liberated” from their former owners. The most voracious of these Normans were the de Hauteville sons, brothers, and half-brothers who came to Italy to avoid primogeniture at home. In Italy, each of the brothers could build his own kingdom, independent of parental whim.

So successful were these Normans that by 1047, the eldest surviving brother, Drogo de Hauteville, had been formally invested in his holdings in southern Italy by the Holy Roman Emperor himself, Henry III of Germany. Drogo was named the Count of Apulia, and with his investment the Normans had suddenly become legitimized in the eyes of the law. Neither the Lombard princes, the Pope, the Byzantines, nor the southern Italian Apulians and Calabrians (provinces of southern Italy) were at all happy with this situation because it consolidated the Normans in their right of conquest.

Legitimacy did not stop the Normans from pursuing their policy of systematic pillage and destruction. If a Norman lord wanted a portion of land, he took it. If he was opposed, he eliminated the opposition with either guile or violence. It must be remembered that the ancestors of the Normans were the Vikings, and the Viking affinity for taking what they wanted had not died out in the Norman psyche. In fact, the Normans (“Norse-men,” or “Northmen”) had carried their Norse legacy even further, trading in their longships for warhorses, which allowed them to ride down their enemies in battle and claim the disputed lands in question.

A few years later, in 1050, Pope Leo IX was made fully aware of how the Normans were regarded by their neighbors. He received a letter from the Abbot of Fecamp which read: “The hatred of the Italians against the Normans has reached such a degree that it is impossible for a Norman, even if a pilgrim, to travel in Italy without being stoned, beaten or thrown into irons, even if he escapes being murdered in prison.” Obviously, a powder keg was waiting to explode.

Leo had been hearing complaints for years and was determined to put a leash on the Normans once and for all. After all, he was the Pontiff and held supreme ecclesiastical power in Italy. The Pope summoned Drogo de Hauteville and told him in no uncertain terms to halt the Norman depravements or face papal wrath. Drogo was one of the more diplomatic of the Norman lords and knew that remaining on at least speaking terms with the Pope was essential to survival in a still hostile land (there being only a few thousand Normans and their followers in Italy at this time). He dutifully agreed to do as the Pope asked, but the Normans were not a unified group and his control was very limited. He could actually do little to control the individual Norman leaders and their followers, who continued as before regardless of what Drogo told them.

The Byzantines too felt that the Normans were a detriment to the political stability of the region. In one instance, the Byzantines brought the southern Lombard princes together in a conspiracy to rid Italy of the Normans. Geoffrey Malaterra, one of the historical writers of the time, wrote in his Histora Sicula that the Lombards of Apulia were “always a treacherous race, [and with the help of Byzantine gold] arranged secretly that all Normans should be murdered at the same time.”

The uprising occurred on August 10, 1051, and Drogo became one of the casualties; he was brutally hacked to pieces while he was at his prayers. Many Normans managed to escape the carnage, often fighting their way out of towns and villages. These survivors swore fealty to Drogo’s brother, Humphrey de Hauteville, the new Count of Apulia. The Normans wasted little time in exacting a horrible revenge. According to William of Apulia, the murderer of Drogo, a Lombard named Riso, “had his limbs torn off one after the other and was then buried alive.” Other conspirators were impaled, their bodies left to rot in the hot summer sun as a warning to others that the Normans made terrible enemies.

Instead of cowing the Lombards, these actions infuriated them all the more, as they did Pope Leo, who was now being seen as ineffectual at controlling the Norman invaders. In fact, Drogo had been the one Norman who had tried to actively work with the Pope to restrain the Normans. Now he was dead and his successor, Humphrey, did nothing at all to hold back the Normans as they inflicted retribution on the Lombards. In desperation, Leo tried to gain the support and aid of the Holy Roman Emperor as well as the King of France to step in and take control of the situation. Unfortunately, both were involved with more immediate problems at home and refused to commit to any help.

Meanwhile, the Byzantine co-conspirators were anything but idle. The Lombards had actually done them a favor in declaring an unofficial war on the Normans. Although the Normans were not destroyed outright, they had suffered casualties that could not be quickly replaced. Argyrus, the Byzantine commander in Italy, offered an alliance to Pope Leo, explaining that their interests were much the same: ridding Italy of the Normans. This would be a very tough decision for the Pope. The Byzantine Church was separate from the Roman Catholic Church and had always been hostile toward Rome. Yet, despite this and the threat of Greek religious influence spreading into Italy, Leo accepted the alliance.

How useful could such an alliance be for the Pope and Rome? The Byzantines were involved with wars at home, notably against the Pechenegs and Seljuq Turks. Yet, the Byzantine Empire had enormous monetary resources with which to fund an anti-Norman alliance in Italy, and Leo felt that he might also be able to help restore the Eastern Church to Roman Papal leadership. Leo easily convinced almost all of the Italo-Lombard princes who had been plundered and raided by Norman adventurers to join with him. By the end of 1051, he had a plan of action.

One major Lombard ruler who did refuse to join in the alliance against the Normans was Gaimer of Salerno, the last powerful Lombard ruler in southern Italy. Salerno had been saved by Norman mercenaries from an attack by Saracen invaders in 1016, thus the ties between him and the Lombards’ enemy were quite strong. Gaimer’s refusal to join the papal alliance, however, was one of family ties as well as expedience. He was related by marriage to a Norman lord and had formerly regarded the Normans as loyal “vassals” as well as strong allies and had no reason to fight against them. The narratives are a bit confused about what actually caused his brothers-in-law to rise up and murder Gaimer—perhaps it was papal intrigue, Byzantine money, or even something as simple as jealousy—but that is what they did in June 1052.

The murder of Gaimer was the spark that brought all of the factions together for the climactic battle at Civitate. The Normans, unable to allow the murder of their ally and friend to go unavenged, marched on Salerno. They easily captured the city and, after agreeing to terms to let them go free if they surrendered, turned on and killed the conspirators who had murdered Gaimer. This action incensed the remaining Italo-Lombards.

The time had now arrived for papal action, so Leo traveled north to Germany in an effort to recruit troops for his growing army. He again appealed to Henry III, the Holy Roman Emperor, for help, but the German ruler refused to join the “crusade.” Nonetheless, Pope Leo and his army commander, Frederick of Lorraine (and later Pope Stephen IX) rode back to Italy at the head of a force of 700 Swabian heavy infantry—deadly fighters who wielded long, two-handed swords in battle. In addition to these tough warriors there also marched, as modern historian John Julius Norwich noted, “a motley and undisciplined collection of mercenaries and adventurers, most of whom thought it wise to leave Germany.”

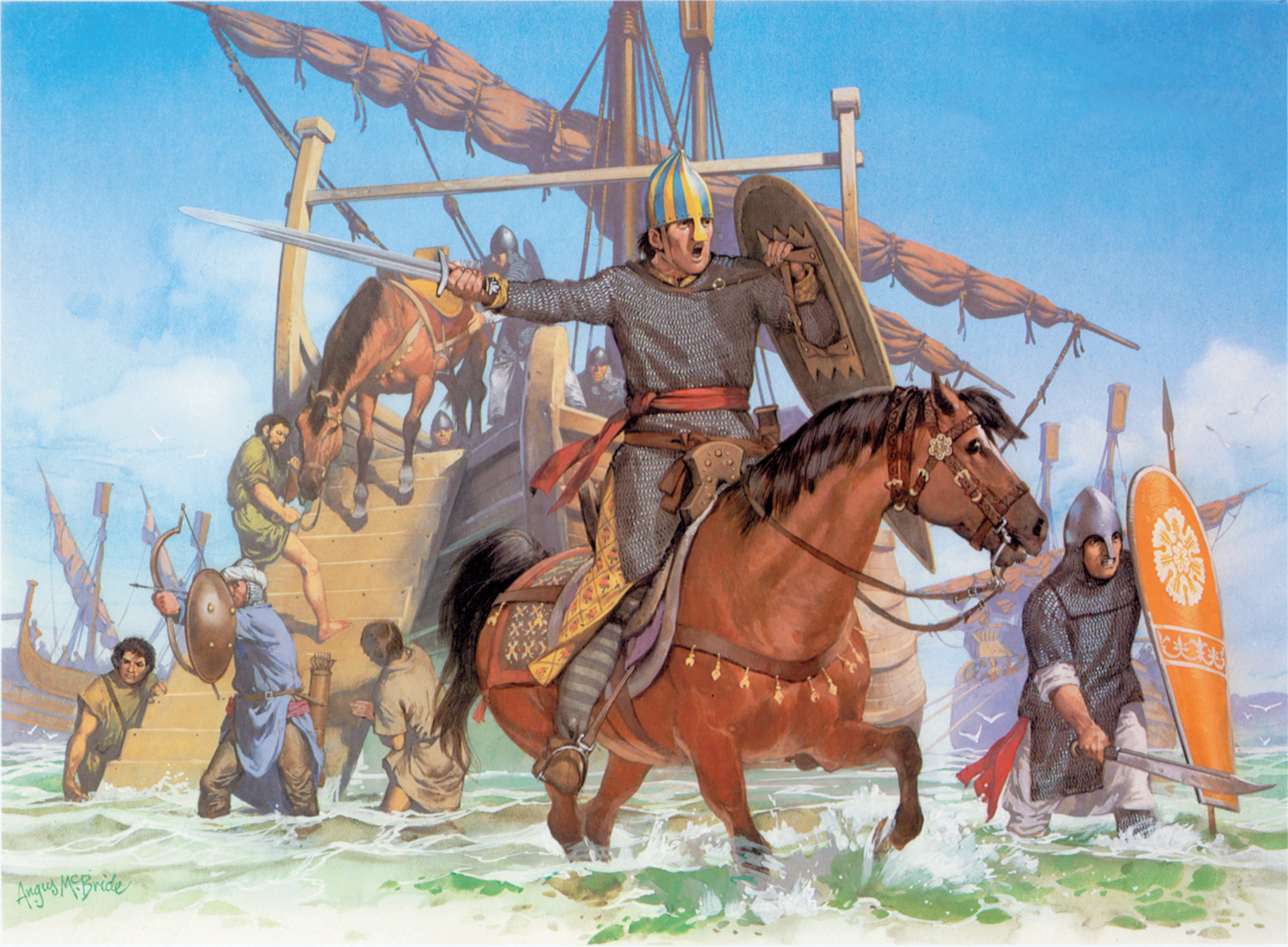

Leo arrived back in Italy in 1053 and began to augment his German army with Italians and Lombards. This was not difficult because most had a grudge of one kind or another to settle with the Normans. Joining together at the central gathering point at Benevento in June of 1053 was virtually every single Italo-Lombard lord in southern Italy, with only Salerno remaining out of the fight.

The Norman leaders had no choice; they had to fight together or be destroyed individually. Humphrey was no fool and realized he was in deep trouble. The Normans looked at the situation and saw that, as Norwich noted, “Ranged against them were not only two armies, the Papal and the Byzantine, but also the entire indigenous population of Apulia…. On their side they had only their formidable military reputation; courage, cohesion and discipline; and their own swords.” Even with the frightful odds and seeming hopelessness of the coming campaign, Humphrey did not give in to his fears. Instead, he called the Normans together for a war parley.

From the west coast of Italy came Richard of Aversa, a powerful Norman ruler in his own right. Richard (also called Rainulf of Normandy) had been an early arrival from Normandy, settling into his lands and marrying into the Lombard aristocracy in 1030. From the south came Humphrey’s younger half-brother, Robert de Hauteville, called Guiscard (“The Cunning or Wary”) by his neighbors and enemies. These formidable leaders brought with them all the Normans and reluctant Italian “allies” they could gather together for the upcoming battle. Salerno, now under the rule of Prince Gisolf, remained neutral, refusing aid to either side. William of Apulia estimated the Norman strength at 3,000 horse. (This total seems very high, since it is unlikely there could have been that many Norman knights and retainers in Italy at this time. A figure perhaps half this size or less would be more accurate. It undoubtedly included any reluctant allies who were brought along, as well as the footmen who accompanied the Normans.) In any event, it was a small army with which to fight against the growing forces of Pope Leo and the Byzantines.

Pope Leo’s campaign plans for ridding Italy of the Normans in 1053 was sound. He would march his growing army northward, fording the Biforno River and move through the valley of Fortore, crossing the plain of Capitanata to join the Byzantines under Argyrus at Siponto on the Adriatic coast. This was a rather circuitous route, but the army would be able to avoid assaulting any Norman fortresses, which would have slowed them down. The combined Lombard and Byzantine army would be more than a match for anything the Normans could field.

The Normans also had a sound plan. They would rely on the age-old strategy of divide and conquer. They did not intend to allow the papal army to join with the Byzantines. The Normans were badly outnumbered even facing a single portion of the alliance, but fighting the combined armies would be an impossible task. Humphrey planned on intercepting the papal army as it crossed the Fortore River, thus preventing it from joining the Byzantines, who were camped at Siponto.

Humphrey’s speed and direct approach worked. The papal forces were two days’ march from Siponto when their advance patrols ran into the Normans near the old Roman city of Civitate. The Germans leading the papal vanguard quickly rode back with the news of an army of unknown size guarding the road north.

Lupus Protospatharius wrote that 1053 had been a year of famine in southern Italy, making foraging difficult for the Normans, who did not rely on a supply train but lived off the land. The locals in their path did their best to sell their available provender to the papal forces, thus denying it to the Normans. Sources note that the Normans were near starvation by the middle of June. They gathered what they could from the barren fields, including green wheat which they rubbed between their hands or on rocks to soften it before eating it.

The Battle of Civitate is fairly well documented. The Norman chroniclers, William of Apulia, Geoffrey Malaterra, and Aime of Monte Cassino provide details of the battle, first noting that the Normans hoped to avoid a pitched battle even at the 11th hour.

The Normans were realists—if they lost, they would be destroyed. Furthermore, they had serious reservations about fighting against the Pope, the “Vicar of Christ” and their Holy Father. They therefore sent Richard of Aversa with a small group of knights to the papal camp to swear fealty to the Pope and pledge their loyalty, offering to hold their lands as vassals to him.

Frederick of Lorraine was all for talking to the Normans. He did not intend to accept their pledges, but instead planned to use the time gained by the talks to send messengers to the Byzantines telling them to make haste to catch the Normans between the two allied armies. Pope Leo did not intend to back down either. In response to the Norman proposals, he acceded to Frederick of Lorraine who, according to William of Apulia, boasted that with a mere one hundred “effeminate” German knights, he would destroy the Normans and that “long-haired Germans, because of their tall bodies, derided the smaller stature of the Normans and paid no attention to the envoys of a race whom they deemed their equal neither in numbers nor physique.” He then told Pope Leo as the Norman envoys stood before them, “Order the Normans to lay down their arms and leave Italy…. If they refuse … not yet have they felt German swords. Let them depart or perish at our hands.”

The Germans began shouting for the death of the Normans as the Norman envoys mounted up and rode back to their camp, no doubt grateful they had escaped with their lives. There would be no negotiated peace.

That evening the Norman lords held a counsel of war to decide on tactics for dealing with the papal army gathered before them. Simply put, they would have to decisively defeat the enemy quickly before the Byzantines had a chance to march to the battle. It was determined that a dawn attack would be made on the enemy army, hopefully catching the papal forces before they were fully formed up and deployed for battle.

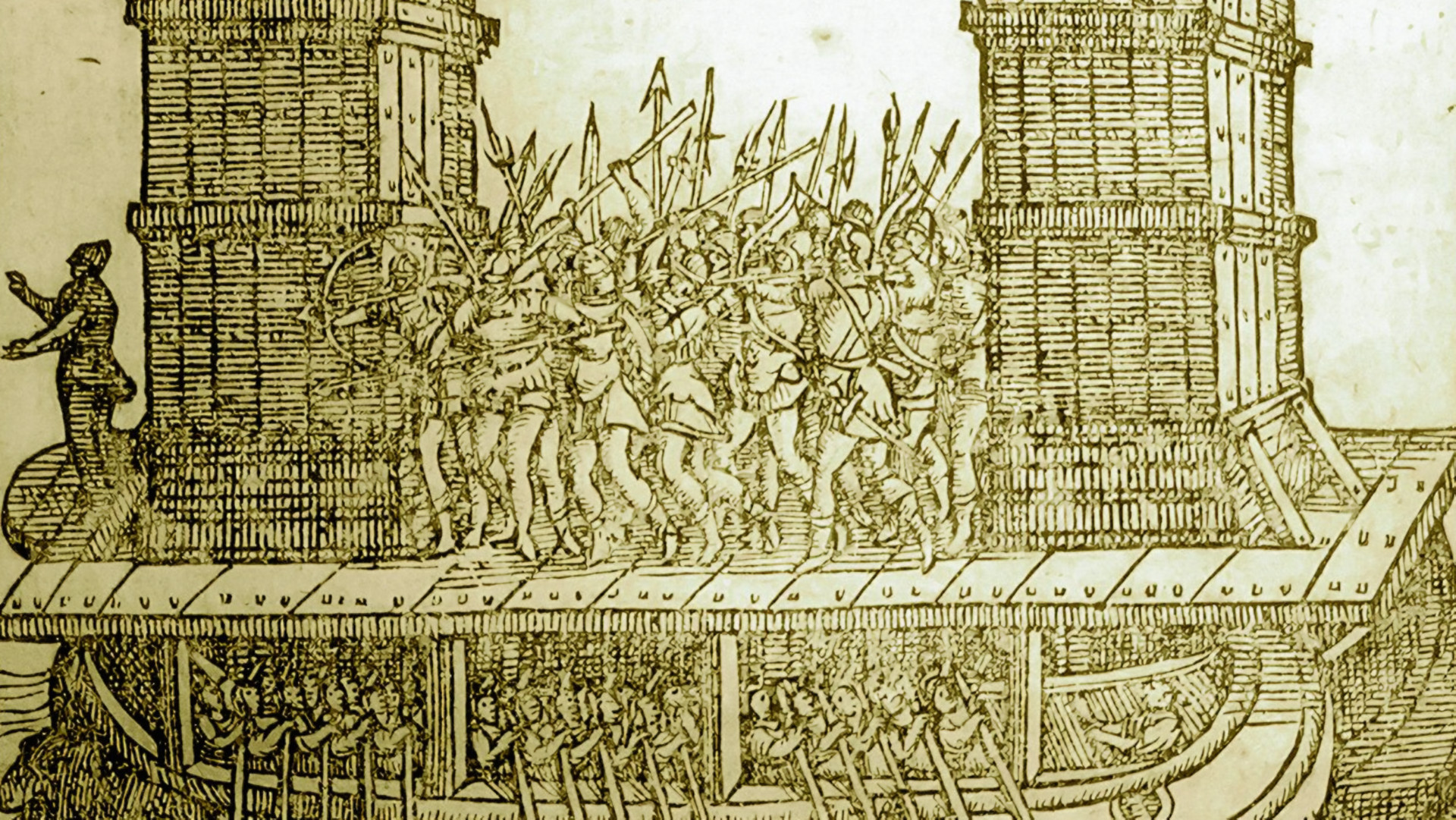

The papal army gathered around the town of Civitate numbered between 3,000 and 5,000 men, including the Swabian and German mercenaries. It was at least twice the size of the Norman army, though numbers often meant little in the scheme of things. In over half the battles in which numbers of combatants were reported in the early medieval period, the smaller army won. This was usually the result of better quality leadership, troops being of higher morale, or having better technology.

The battlefield at Civitate between the town and the banks of the Fortore consisted of a relatively flat plain and some low hills. One particular hill hid the Norman army from the papal forces, and on the morning of June 18, 1053, several Normans, including Humphrey, climbed to the top to scout out the dispositions of the papal army.

In the quiet, late spring morning, the Normans could see that the Swabians had taken up positions on the extreme right of the enemy line. They were easily sighted because of the papal banner in their midst and the glint of chain mail armor that all the Swabians wore, unlike their allies, of whom only the knights and nobles were armored. The Italo-Lombards were deploying in a rather desultory fashion in the center and left. Humphrey had determined the night before to divide his forces into three divisions, or “battles.” Richard of Aversa would command the right-hand battle, while Humphrey would take the largest, center battle and the left battle. Robert Guiscard would be in charge of the third battle, which would remain in a reserve capacity to support the other attacks as needed.

The Norman battle plan was complex for the period. Richard would lead an all-out frenzied charge against the Italo-Lombards, tying them up, while Humphrey took on the Swabians with the strongest portion of the Norman army. Robert Guiscard would hold his command back, a difficult task with excited and eager knights wanting to close and fight with their enemy. But his task was the most important of all: to attack at the critical point in the battle or, if disaster occurred, to cover the Norman retreat and save the rest of the army from destruction. Determined to achieve victory as well as avenge themselves of German insults, the Normans mounted up and began to move out.

Two things favored the Normans. First, they were going to charge out from behind a hill, which masked much of their initial movement from papal view. Second, they were facing many of the same troops they knew were inferior to them in battle, at least insofar as the Lombards and Italians were concerned. Both the Normans and the Italo-Lombards knew this. The Swabians were another matter. They alone outnumbered the entire Norman central division, but Humphrey reasoned that if the Italo-Lombards could be swiftly defeated, the Swabians could be dealt with on nearly equal terms.

First to round the hill were Richard of Aversa’s knights. Raising their war cry of “Dex ais!” they broke into a canter and charged headlong toward the Italo-Lombards. Behind them rode Humphrey’s division, charging down upon the Swabians while Robert led his men in a slow trot, keeping his command under tight control.

Frederick of Lorraine, riding back to join Pope Leo on the walls of Civitate, left the Swabians under the command of the two German generals, Garner and Albert. As Leo watched the battle develop before him, he made the sign of the cross, absolved his army of their sins, and commanded the troops to attack. Seeing the signal from the wall, the German leaders raised the papal banner and shouted “Got mit uns!” (“God is with us!”). The Swabians raced toward the advancing Normans alone. The Italians refused to advance in conjunction with the Germans. They simply milled around as the Normans bore down on them.

The Italo-Lombard line shuddered as the Normans crashed into them. Unable to withstand the shock of the attack, the troops broke and fled from their attackers. One minute they were there, the next they were casting their weapons away and fleeing for what safety they could find. In their panicked flight, many were trampled to death by their own people. The Normans began to slaughter the rest. William of Apulia provides us with the details: “As victims of the bird of prey, so fled the Italians before Richard. But flight failed to save them. Richard and his companions pursued heedlessly, without thought of the other Normans, and succeeded in overtaking them. Then perished a great part of the Italian soldiers, only a few escaping.”

Humphrey’s attack tore into the packed German cavalry, but the Swabians, while not great fighters on horseback, managed through sheer weight of numbers to halt the Norman attack. Humphrey ordered a withdrawal, reformed, and charged again. Seven times the Normans charged the Swabians, each time unable to break the Germans. Humphrey was knocked from his horse twice.

The Normans became inexorably stuck in the midst of the German division. Surrounded, outnumbered, and tiring rapidly, Humphrey looked in vain for Richard of Aversa to return from his pursuit of the defeated Italo-Lombards. The melee raged. William of Apulia related: “There were then formidable sword strokes on both sides; men struck on the head were cut in two, and often the same blow killed both horse and rider.”

At this point Robert Guiscard launched his reserves into battle. Robert’s hundred or so knights tore into the German flank, causing them to waver, but not to break. There were still too many of them. Robert’s Normans screamed in anger as they saw their brethren lying crushed and broken beneath the German mounts. Robert had seen his own brother fall and thought him badly wounded. William of Apulia (quoted in Norwich) noted Robert’s determination and power as he fought his way through the mass of men: “… varied [were] the means he employed; some had feet lopped off at the ankles. Others were shorn of their hands, or their heads sliced from their shoulders; Here was a body split open, from the breast to the base of the stomach; Here was another transfixed through the ribs, though headless already. Thus the tall bodies, truncated, were equaled in size [with that of the smaller statured Normans].”

Robert exhorted the Swabians with oaths, boasts, and threats as he cut them down. Three times his horse fell beneath him. Three times he took another and continued to fight.

Yet, the Normans were losing. The Germans simply overwhelmed the Normans and cut them down. Exhaustion was setting in as horses simply could not make another charge and men could barely raise their swords or lances. The Swabians continued to fight with skill and courage. It was beginning to appear that Richard of Aversa’s easy victory over the Lombards would actually cost the Normans the battle.

It was then that Richard returned, reportedly smiling as he cried, “O! unfortunate my success when there are those who still dispute us,” and led his knights into the rear of the Swabians.

At this point the German generals, Garner and Albert, ordered their men to dismount and fight on foot, allowing the more judicious use of the two-handed sword. The several hundred survivors did just that and the battle continued. The Swabians were now exhausted and disheartened as well, seeing that the Normans would not quit, but they continued to fight to the death. The Germans formed themselves into protective circles to defend themselves from all sides.

The Normans drew back in groups, managing to rest their horses for a time, while other groups charged the circles, thrusting their long lances into the Germans’ compact bodies. The Swabians were unable to reply without charging out of their formations and exposing their backs to Norman lances. Slowly, steadily the Swabians fell beneath the Norman attacks. As the last group of Germans was cut down, the Normans turned toward the walls of Civitate where Pope Leo could only stare in horror as the last of his army bled to death before him. The Battle of Civitate rang to a close.

The town could not hold out against the Normans, and Leo sent out a letter asking them to make penance for the lives they had destroyed while at the same time offering his own surrender. The townspeople of Civitate delivered him to the Normans, who suddenly fell to their knees and begged his forgiveness for their sins.

Leo’s political policy and influence were destroyed at Civitate. Geoffrey Malaterra even goes so far as to state that Leo invested the Normans in their lands and also gave them permission (and Holy sanction) to subdue the province of Calabria as well as Muslim Sicily, holding both in the name of St. Peter. There is, however, no other evidence of this.

There is no doubt that the victory won the Normans Italy by the right of conquest. With the deaths of Pope Leo the following year, the Byzantine Emperor Constantine a year after that, and the Holy Roman Emperor Henry III in 1056, the chances of bringing about an anti-Norman revival were at an end.

The Normans in Italy would soon take their aggression to Sicily and Greece. That aggression would further be evidenced at the turn of the century when Crusading fervor would give full vent to Norman adventurism.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments