By Al Hemingway

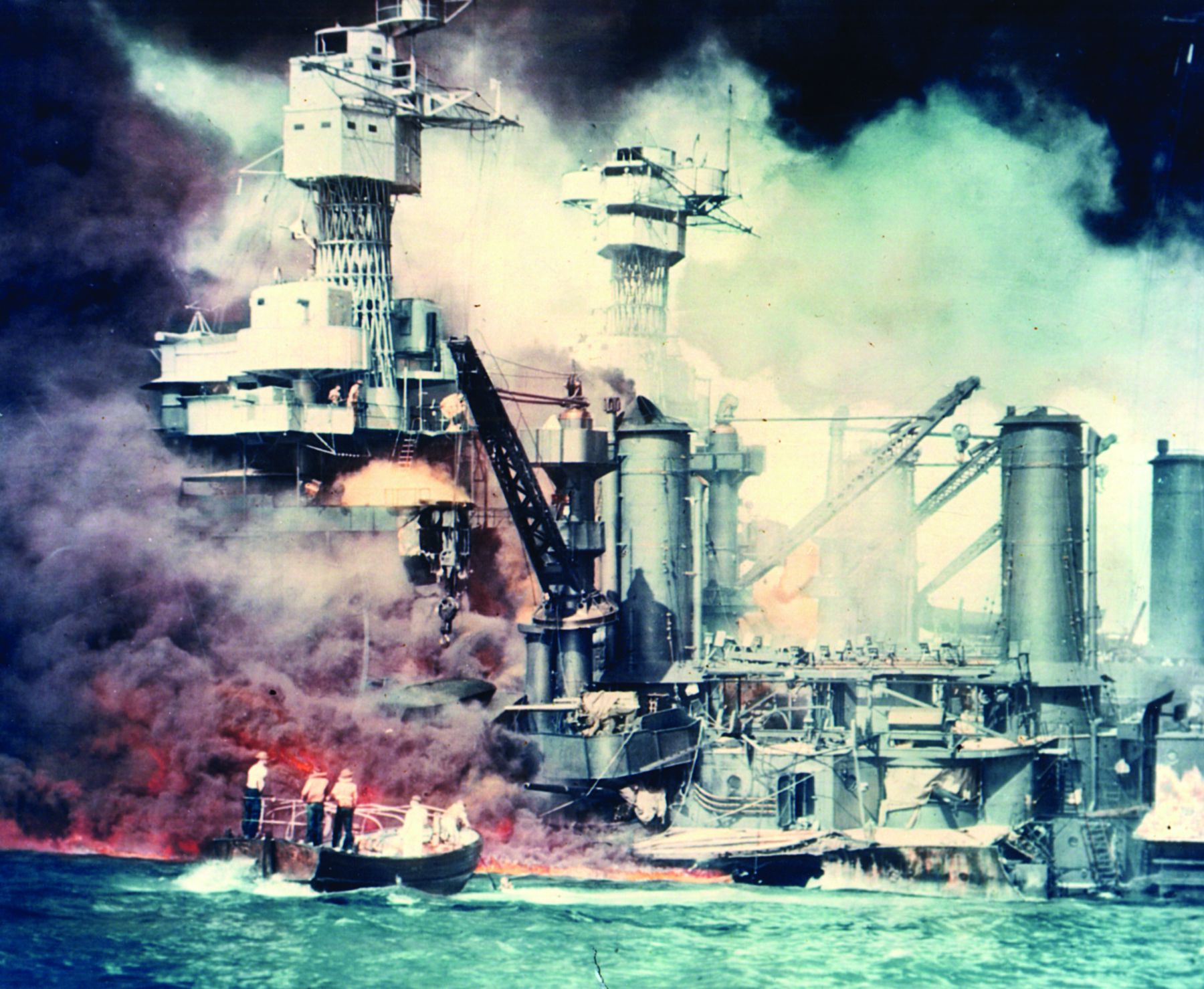

Nearly seven decades after the sneak attack on Pearl Harbor by the Japanese Navy and Air Force on the morning of December 7, 1941, controversy still surrounds the history-changing event. Numerous books and articles have been written assessing the military and political situation at that time. The nagging question has always remained: “How much did our lead- ers know ahead of time and, if so, who was to blame for the failure to alert the American fleet in Hawaii?”

In Skipper Steely’s new book, Pearl Harbor Countdown: Admiral James O. Richardson (Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, LA, 2008, 543 pp., photos, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover), readers are given a rare glimpse into what transpired prior to the assault from an individual who had unimpeachable firsthand knowledge: Admiral James O. Richardson, commander of the American fleet in the turbulent days before the onset of World War II.

In Skipper Steely’s new book, Pearl Harbor Countdown: Admiral James O. Richardson (Pelican Publishing Company, Gretna, LA, 2008, 543 pp., photos, notes, index, $35.00, hardcover), readers are given a rare glimpse into what transpired prior to the assault from an individual who had unimpeachable firsthand knowledge: Admiral James O. Richardson, commander of the American fleet in the turbulent days before the onset of World War II.

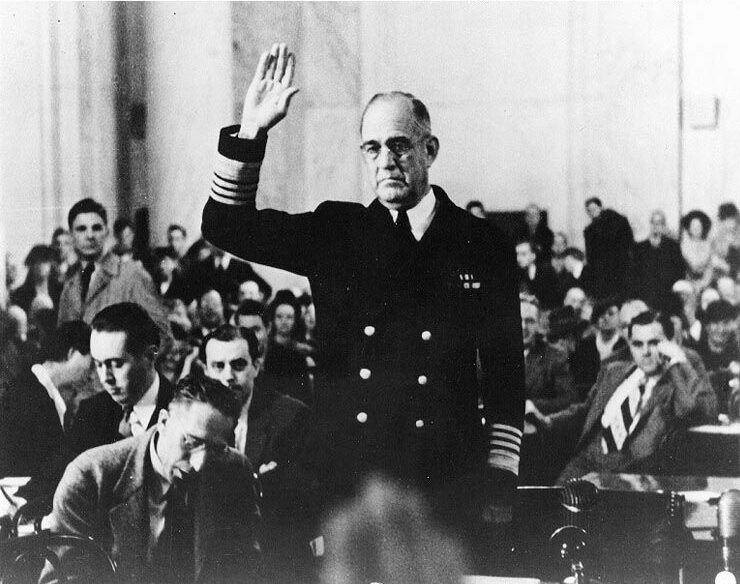

Born in Paris, Texas, in 1878, Richardson graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1902. He went on to hold numerous positions before President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him commander-in-chief of the U.S. Fleet. Richardson’s pleas for more men and supplies and repairs to his ships fell on deaf ears in Washington. He openly disagreed with FDR’s decision to station the fleet permanently at Pearl Harbor and argued about what he called the “inadequate anchorages, airfields, recreational venues, and other necessary facilities to care for thousands of sailors.”

Richardson later wrote: “In 1940, the policy-making branch of the Government in foreign affairs—the President and the Secretary of State—thought that stationing the Fleet in Hawaii would restrain the Japanese. They did not ask their senior military advisors whether it would accomplish such an end. They imposed their decision upon them.” The Texas native also spoke out publicly about how the U.S. Navy was totally unprepared for combat. The Axis powers had been in a war mode for years, he said, and in those dark days as the world witnessed the military conquests and ultimate subjugation of the people of Europe and Asia by the Nazis and the Japanese.

After a meeting with Roosevelt in the fall of 1940, in which Richardson warned that the “senior officers of the navy do not have the trust and confidence in the civilian leadership of this country,” the president quietly made arrangements to have him relieved of command. On February 1, 1941, Richardson turned over the responsibility of the American fleet to Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, whose own career would be ruined after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor 10 months later.

How much did Richardson know? Although kept in the dark about many issues, especially the breaking of the Japanese code, he fully realized that the United States would ultimately have to enter hostilities against Japan and Germany. Richardson authored a book of his own entitled On the Treadmill to Pearl Harbor. Unfortunately, he later burned his diary and other pertinent documents before his death in 1974 that might have shed important information on the strategy—or lack of one—before the Japanese sneak attack.

Although Richardson did not trust Roosevelt personally, he was careful not to accuse him of intentionally placing the fleet in harm’s way at Pearl Harbor. Martin Merston, a reviewer for the Journal of Historical Review, wrote of Richardson’s book: “It should be noted that Richardson has not in any way suggested that FDR deliberately stationed the Fleet at Pearl in order to ‘bait’ the Japanese to attack. Such an implication might be derived from a similar set of facts, but Richardson, to his dying day, remained a dedicated naval officer, not a politician, thereby embodying the highest traditions of the Navy.”

Military intelligence overlooked, prescient warnings from experienced commanders ignored, administration critics demoted and demonized—it all sounds uncomfortably familiar today. And in the end, FDR actually won the war that had been forced upon him.

The Second Battle of the Marne by Michael S. Neiberg, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2008, 217 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

The Second Battle of the Marne by Michael S. Neiberg, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2008, 217 pp., illustrations, maps, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

The beautiful Marne River valley, located in the northeast section of France, was the scene of much bloody combat during World War I. In 1914, British and French forces combined to hold off a massive German assault in the region by the “narrowest of margins.” Four years later, in 1918, German General Erich Ludendorff devised a plan that would punch a hole in the Allied lines and enable the Germans to race to Paris and sue for peace from a position of strength. On July 15, 23 German divisions attacked the French Fourth Army in the east. Meanwhile, another 17 divisions struck the French Sixth Army on the western flank. Although, both assaults were eventually stymied, the German drove dangerously close to the French capital.

German casualties in the failed campaign were estimated at 168,000. Allied dead and wounded, including the newly arrived American Expeditionary Force, totaled approximately 120,000. Ludendorff’s audacious scheme backfired, and Germany ultimately lost the war.

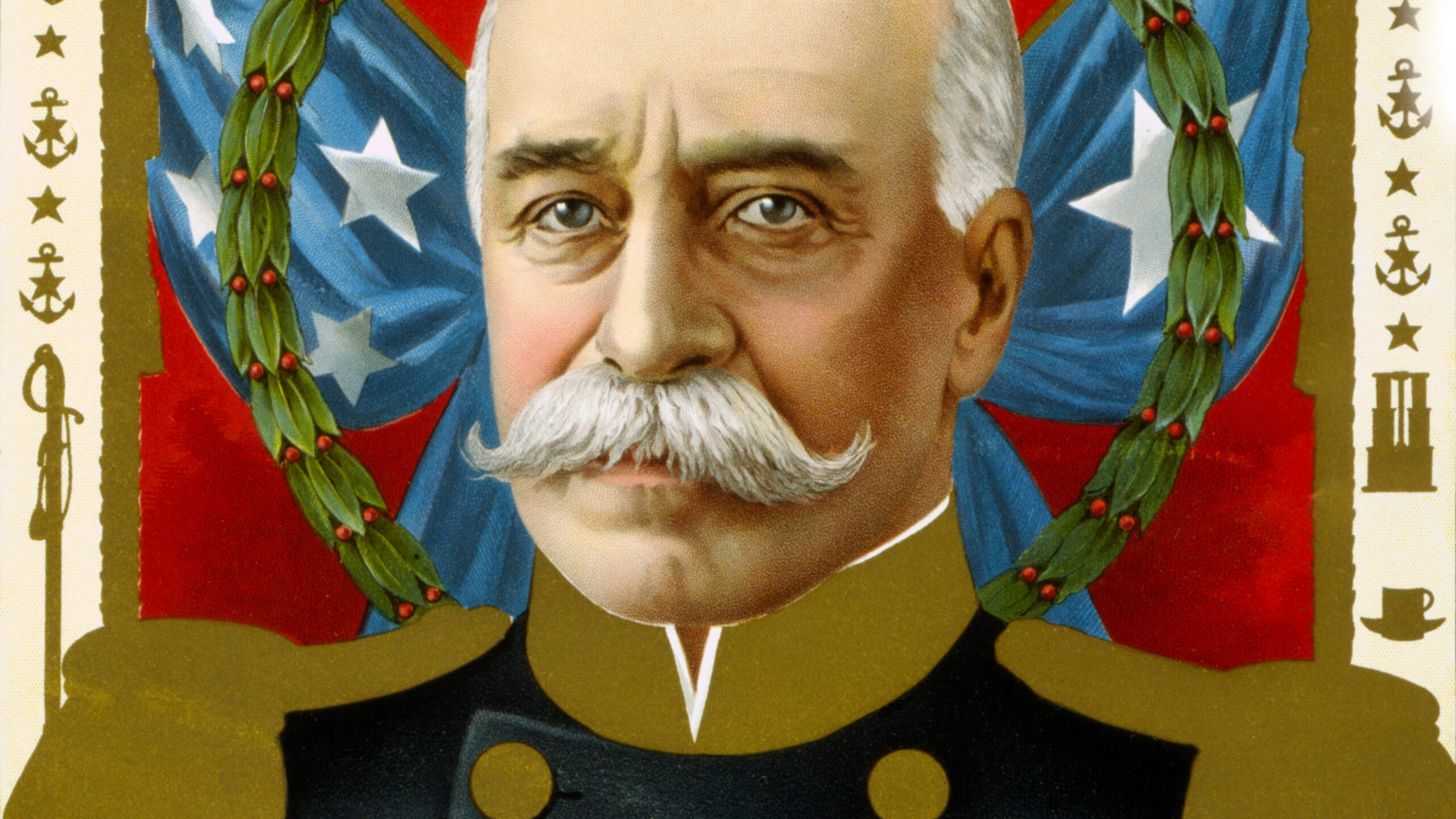

Neiberg reexamines the role of the French Army and its commander Ferdinand Foch during the second Marne campaign. He notes that the opinions surrounding the French Army were “universally full of praise and admiration” from both British and Americans. He also praises Foch’s role during the battle and how he “proved a keen sense of what the Germans opposite him were trying to accomplish.”

The Second Battle of the Marne did not alter the outcome of the war for the German government. It only managed to send thousands more Allied and German soldiers to their premature deaths on the killing fields of the serene and pastoral Marne River valley.

Chief of Staff: The Principal Officers Behind History’s Great Commanders, Volume 1, edited by Maj. Gen. David T. Zabecki, AUS (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 241 pp., illustrations, notes, $39.95, hardcover.

Chief of Staff: The Principal Officers Behind History’s Great Commanders, Volume 1, edited by Maj. Gen. David T. Zabecki, AUS (Ret.), Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2008, 241 pp., illustrations, notes, $39.95, hardcover.

Teamwork is an essential part of any joint undertaking. Individuals from every conceivable occupation and background form bonds to organize and complete a project successfully. The military is no exception. One of the most important roles in the military chain of command is the chief of staff. It is his job to assure that the commander’s plans are interpreted correctly so that they can make a smooth transition from battlefield maps to the battlefield itself. This essential duty not only promotes victory, but also saves lives.

This book is a collection of brief profiles of well-known chiefs of staff throughout military history, written by eminent historians and retired military officers, from the Napoleonic era to World War I. Each chapter is preceded by a chronological time line of the person’s life.

Perhaps the premier chief of staff was Louis-Alexandre Berthier, who served in that capacity for Napoleon in his numerous campaigns. Described as the quintessential chief of staff, Berthier proved invaluable to the “Little Corporal” as a liaison between the commander and his junior officers. He was extremely efficient and could memorize the locations and troop strength of each command in the army. Unfortunately, Berthier, brilliant as Bonaparte’s right-hand man, was incapable of commanding an army in the field. Although serving on Napoleon’s staff for many years, he never successfully grasped his leader’s astonishing talent for strategy and boldness during battle.

Chief of Staff is an enlightening and entertaining work that informs the reader about the important duties of the titular military position. Although it is the commander who receives the accolades if he achieves victory, it is often the man behind the scene, his chief of staff, whose invaluable assistance makes it possible.

Flying the SR-71 Blackbird: In the Cockpit on a Secret Operational Mission by Colonel Richard H. Graham, USAF (Ret.), Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 304 pp., photos, index, $25.95, hardcover.

Flying the SR-71 Blackbird: In the Cockpit on a Secret Operational Mission by Colonel Richard H. Graham, USAF (Ret.), Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2008, 304 pp., photos, index, $25.95, hardcover.

When the people of Okinawa first saw the slender, evil-looking black SR-7 for the first time, they would point skyward and exclaim “Habu!” It was the name of a poisonous pit viper of the same color that inhabited the island. Although often referred to as the Blackbird, the nickname of “Habu” stuck. From 1964 until 1989, the SR-71 patrolled enemy skies, logging more than 17,000 sorties. With only 32 of the planes built, and a dozen of these destroyed in accidents, the Blackbird crews constitute a small and unique alumni organization.

The author himself is a member of that distinguished group. For 15 years, he worked within the SR-71 community, commanding the 1st Strategic Reconnaissance Squadron in 1981. Graham has more than 4,600 flying hours to his credit, as well as a host of awards and decorations. He goes into detail about every facet of the aircraft. It could reach a speed of Mach 3 and altitudes of over 80,000 feet. Because the Blackbird could attain such unprecedented altitudes and speed, not one was ever shot down by an enemy surface-to-air missile.

Graham’s account of his time as a Blackbird pilot is fascinating. His book is the definitive story of the complex duties and secret missions flown by the crews of the dreaded “Habu.”

True Sons of the Republic: European Immigrants in the Union Army by Martin W. Ofele, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, 2008, 200 pp., photos, notes, index, $49.95, hardcover.

True Sons of the Republic: European Immigrants in the Union Army by Martin W. Ofele, Praeger Publishers, Westport, CT, 2008, 200 pp., photos, notes, index, $49.95, hardcover.

“Stand by the Union; Fight for the Union; Die for the Union!” was the northern battle cry in the early days of the American Civil War. Thousands flocked to enlist when President Abraham Lincoln called for volunteers to fight after the Confederacy bombarded Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina, in April 1861.

Included in that influx of would-be soldiers were many individuals who were born in Europe or had recently immigrated to the United States. Although numerous ethnic groups joined the Union cause, the two primary European factions were the Germans and Irish. Prominent Irish and German citizens who had prior military experience in earlier European revolutions quickly organized their own regiments and used their national heritage to urge others to enlist.

The famed Irish Brigade was arguably the most famous. Officially known as the 69th New York Infantry, the unit’s well-known green flag with the harp and Gaelic battle cry of “Faugh a ballagh,” or “Clear the way,” gained them notoriety in numerous Civil War engagements.

As the author states, Abraham Lincoln at the end of the war “certainly made no ethnic distinctions when he wrote: ‘For the great Republic—for the principle it lives by, and keeps alive—for man’s vast future—thanks to all.’”

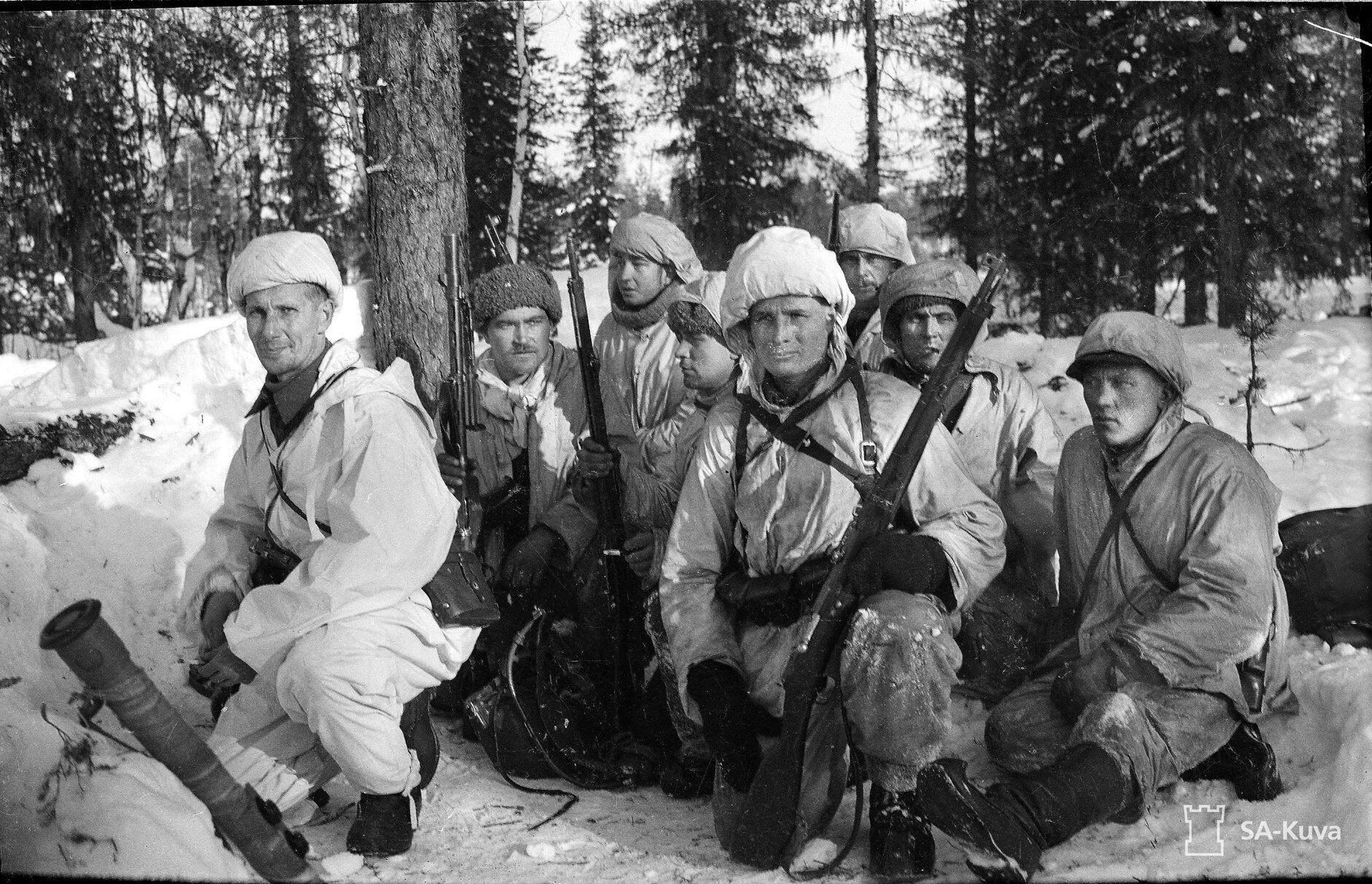

The Mammoth Book of Inside the Elite Special Forces by Nigel Cawthorne, Running Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2008, 551 pp., $13.95, softcover.

The Mammoth Book of Inside the Elite Special Forces by Nigel Cawthorne, Running Press, Philadelphia, PA, 2008, 551 pp., $13.95, softcover.

The top secret and fascinating world of Special Forces has always intrigued historians and history buffs alike. Clandestine operations involving shadowy figures dropped behind enemy lines have been the focus of low-intensity conflicts since the end of World War II.

In his newest account of this unique group, the author describes every facet of what it takes to become a member of such elite units. Training is extremely rigorous to weed out those who cannot endure the taxing life of a member of a Special Forces Team. At the Special Air Service training center in Hereford, England, only 10 percent of candidates successfully pass the induction course.

Cawthorne goes into detail on the various weapons that team members carry, the use of demolitions, insertions and extractions, cold weather training, communications equipment, and clothing they wear. He also gives a brief history of each service’s elite force and describes the various campaigns they have participated in since their formation.

Covert operations have been an integral part of wartime strategy since man has waged war. Highly trained individuals are in constant demand to gather reliable intelligence for the commanders in the field. The sign over the doorway to the training facility for the U.S. Navy SEALs sums it up best: “The More You Sweat in Peace, The Less You Bleed in War.”

Fort Abraham Lincoln Dakota Territory: The Fort Commanded by General Custer at the time of the Little Big Horn by Lee Chambers, Schiffer Books, Atglen, PA, 2008, 172 pp., photos, illustrations, bibliography, $19.99, softcover.

Fort Abraham Lincoln Dakota Territory: The Fort Commanded by General Custer at the time of the Little Big Horn by Lee Chambers, Schiffer Books, Atglen, PA, 2008, 172 pp., photos, illustrations, bibliography, $19.99, softcover.

What was it like to live on a military installation in the late 19th century? What was the daily routine for a soldier? What did they eat? What did they wear? How did they enjoy their off-duty hours?

All of these questions are answered in Lee Chambers’s newest book. A retired police officer, Chambers developed a strong interest in the American cavalry and its history because his father was a member of one of the last horse-mounted units in the U.S. Army. The author goes into great detail on the day-to-day activities of common soldiers at Fort Abraham Lincoln in Dakota Territory. Originally called Fort McKeen when it was constructed in April 1872, the outpost was redesignated Fort Abraham Lincoln later that same year. Fort Lincoln was quite large for the period, housing not only cavalry but also regiments of infantry to protect settlers from the ever-present threat of hostile Indian actions.

The fort’s most noted commander was George Armstrong Custer. On May 17, 1876, Custer, rode out with the 7th Cavalry and one company of infantry to begin his final campaign against the Sioux. Slightly more than a month later, he and 262 of his troopers would be killed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn.

In 1894, Fort Abraham Lincoln was razed, signaling the end of an era in our nation’s history. The day of the horse-mounted cavalry would soon be a thing of the past.

Genghis Khan: History’s Greatest Empire Builder by Paul Lococo, Jr., Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2008, 91 pp., maps, notes, index, $13.95, softcover.

Genghis Khan: History’s Greatest Empire Builder by Paul Lococo, Jr., Potomac Books, Dulles, VA, 2008, 91 pp., maps, notes, index, $13.95, softcover.

Considered by many to be nothing more than a ruthless conqueror, Genghis Khan in fact was a multifaceted individual. The son of a minor tribal chieftain, he had an uncanny ability to organize and inspire loyalty in his men. He did the unthinkable and eventually formed the isolated clans on the Mongolian Steppes into one extremely mobile and powerful force.

Khan took the time to study and gain a better understanding of his opponents. He understood the important uses of propaganda, economic concerns, and diplomacy to conquer an enemy. However, as the author states: “Let there be no mistake, battle was the primary tool for this conqueror.” An incredible warrior, leader, and tactician, Genghis Khan was able to motivate his people and take his mighty hordes to ultimately overrun China, Central Asia and Persia. Whatever his reputation, few military leaders in human history have accomplished so much.

A Military History of India and South Asia: From the East India Company to the Nuclear Era edited by Daniel P. Marston and Chandar S. Sundaram, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2008, notes, index, $24.95, softcover.

A Military History of India and South Asia: From the East India Company to the Nuclear Era edited by Daniel P. Marston and Chandar S. Sundaram, Indiana University Press, Bloomington, IN, 2008, notes, index, $24.95, softcover.

This book is an eye-opener, dealing with the tumultuous military history of India from the arrival of the British in the 18th century to the present day. A collection of 13 articles, each focusing on a specific period, are featured from prominent scholars and historians.

Great Britain’s occupation of India and its concomitant formation of the East India Company is always a captivating topic. Raymond Callahan, history professor at the University of Delaware, goes into exhaustive detail on the Sepoy rebellion of 1857. He notes that the 1857 Mutiny “left a great scar across the face of the British Raj,” and would remain in the British psyche until India won its independence in 1947.

Since that time, India has emerged into the nuclear age. Rajesh M. Basrur, director of the Centre for Global Studies at Mumbai University, asserts that it did so primarily because of disputes with neighboring China, although he points out that Sino-Indian relations have improved considerably in the past decade.

The United States is attempting to bring modern-day India into the world sphere as a “responsible nuclear power.” Basrur feels certain that India will follow a course of “nuclear restraint and remain a cautious and prudent nuclear power.” One can only hope, for everyone’s sake, that he is right.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments