By Patrick J. Chaisson

Captain (Dr.) Willis P. McKee did not like what he was seeing. For several hours now, crowds of panicky civilians had been streaming past his unit’s tent hospital located at a crossroads eight miles northwest of Bastogne, Belgium. A veteran of both the Normandy and Market-Garden campaigns, McKee knew “that something was pushing” those refugees and feared an enemy column could be advancing close behind them.

At dusk on Tuesday, December 19, 1944, he drove to the 101st Airborne Division’s headquarters in Bastogne to report this ominous development to Brig. Gen. Anthony C. McAuliffe, the acting division commander.

Meeting inside the general’s war room, Captain McKee indicated on a map his undefended hospital’s vulnerable location. He also described the throngs of fleeing townspeople he had observed all afternoon. McAuliffe, however, appeared unmoved by this news. “Go on back,” he reassured the young physician, “you’ll be alright.”

Willis McKee’s fears were realized when, barely seven hours later, a large enemy armored force overran the 101st Airborne’s clearing station and took him prisoner. Also captured in the attack were 141 other American soldiers as well as a large quantity of supplies, vehicles, and equipment. With its lone surgical facility now lost, General McAuliffe’s division could no longer provide advanced emergency care to G.I.s gravely injured in the fighting around Bastogne.

The situation worsened on December 21 when German troops cut the last road leading out of town. Now surrounded, those few doctors and enlisted medics left inside the perimeter used a rapidly diminishing supply of medicine and plasma to treat the wounded men who flooded their overcrowded aid stations. For the next five days, they struggled to keep alive as many patients as possible under the most appalling of conditions. Only after General George S. Patton Jr.’s Third U.S. Army opened a corridor into this beleaguered stronghold were ambulance teams again able to evacuate back to proper hospital facilities the hundreds of long-suffering casualties stuck in Bastogne.

When the 101st Airborne Division was first activated in 1942, its force structure included a robust medical department. Yet, in acknowledgement of the Screaming Eagle Division’s status as an air-delivered strike force that often fought behind enemy lines, its health service organizations needed to remain utilitarian, flexible, and able to enter the battlefield either by parachute or glider.

Each of the 101st’s three parachute infantry regiments (PIRs) contained a medical detachment composed of seven officers and 62 enlisted men. The division’s one glider infantry regiment (GIR) counted 8 commissioned officers and 86 enlisted troops in its medical detachment. Additionally, the Screaming Eagles’ field artillery, combat engineer, antiaircraft, and support outfits all had assigned physicians and aidmen.

These detachments constituted the first echelon of medical service within the 101st Airborne Division. In combat, unit aid teams (three enlisted medics per company) provided basic frontline care to sick and wounded soldiers. Litter bearers moved forward from a central battalion aid station (BAS) when required to evacuate those requiring more extensive treatment. At the BAS, aidmen under a commissioned surgeon’s supervision examined and sorted casualties, dressed wounds, administered medication, and prepared seriously injured patients for transport to the nearest field hospital. Each infantry regiment also maintained an aid station responsible for serving the regimental headquarters and service company.

Badly wounded troopers did not stay long in a battalion or regimental aid station. Fleets of jeep ambulances sped casualties who required specialized attention back to the division clearing station, a second-echelon treatment facility run by the 326th Airborne Medical Company.

With an authorized strength of just 216 officers and men, the 326th Med was a pocket-sized organization but one uniquely suited to its mission. It consisted of a Company Headquarters Section, Medical Supply Section, and three platoons (Platoon Headquarters, Litter Bearer Section, Ambulance Section, and Treatment Section). In command was Major (Dr.) William E. Barfield.

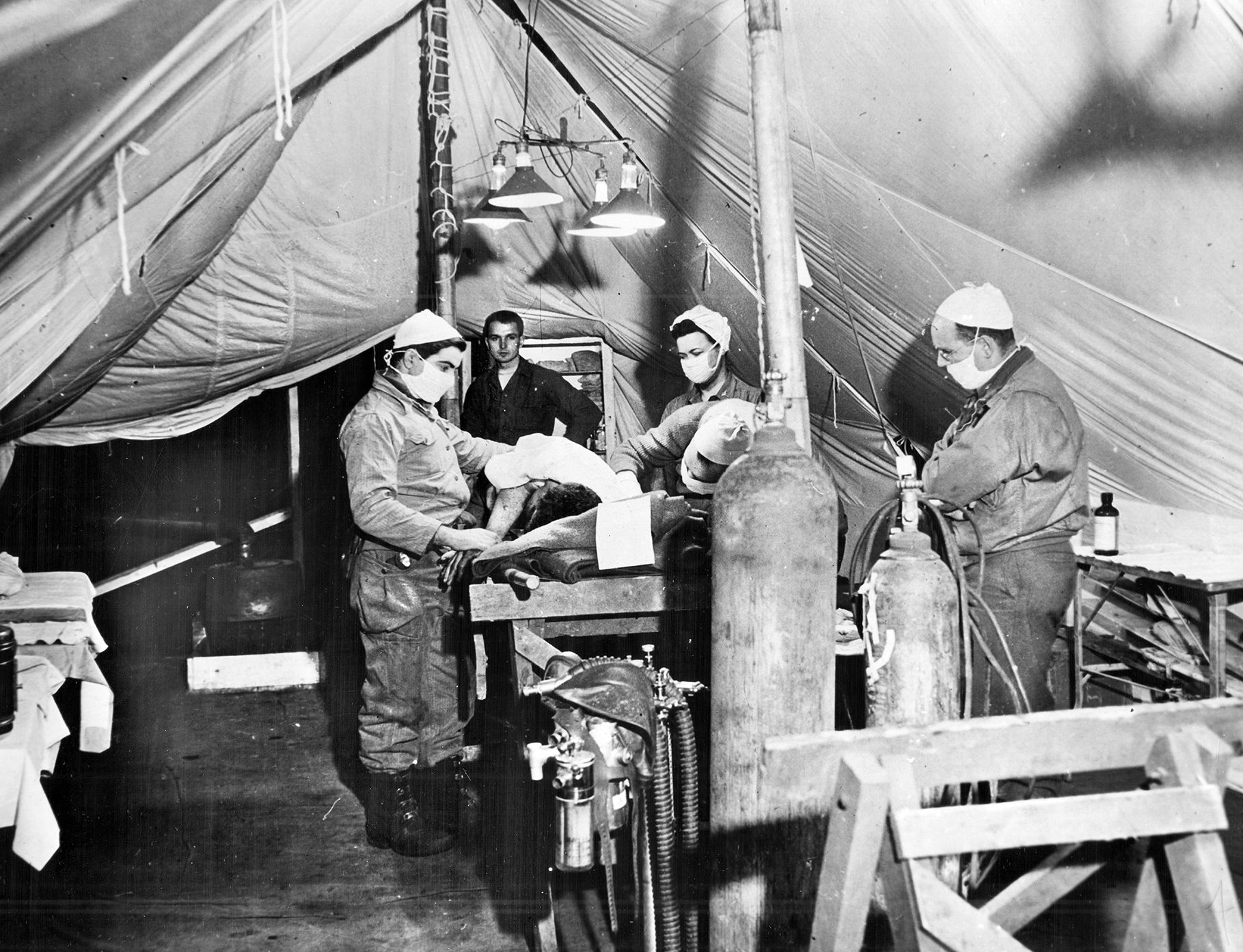

As all its equipment and vehicles had to fit inside CG-4A cargo gliders; the outfit primarily employed jeeps fitted with litter racks to move wounded soldiers. Its clearing station, a set of tents marked with distinctive Red Cross symbols, could be set up within two hours. By itself, though, the 326th Airborne Medical Company possessed neither the apparatus nor the specially trained doctors required to conduct surgical procedures. The unit’s main role was to collect casualties, then triage, stabilize, and ready them for transport to an army level hospital.

Recognizing the Screaming Eagle Division would often operate out of contact with the normal ground evacuation chain, army planners attached to it a team of medical specialists from the 3rd Auxiliary Surgical Group. Four trauma-trained physicians and four enlisted assistants, led by Maj. (Dr.) Albert J. Crandall, performed emergency surgery at the 101st Airborne’s clearing station throughout its campaigns in France and the Netherlands. Crandall’s team remained attached to the 326th Med when in November 1944 that unit moved to a rest camp at Camp Mourmelon, France, after enduring 72 days of intense combat during Operation Market-Garden.

While at Mourmelon, the 326th Airborne Medical Company rebuilt its ranks and replaced broken or lost equipment. By mid-December, the company roster indicated 19 officers and 198 enlisted soldiers present for duty. An additional three officers and two enlisted clerks supported the division surgeon. This staff officer, Lt. Col. (Dr.) David Gold, was responsible for all medical plans, training, and operations throughout the 101st Airborne Division.

On December 17, 1944, the Screaming Eagles were alerted for combat in response to a massive German surprise attack that struck the weakly defended Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg. One of two divisions then designated as European Theater Reserve, the 101st Airborne was needed to bolster an unsteady First U.S. Army, then reeling under intense pressure from thousands of enemy troops, tanks, and guns.

Medical personnel across the division rushed to get ready. Newly assigned replacements followed the old timers’ lead as they efficiently packed individual and unit equipment, including a large supply of litters and wool blankets. Starting at 1800 hours on Tuesday, December 18, the 326th’s troopers departed Mourmelon in a convoy of jeep ambulances and borrowed cargo trucks. After an all-night motor march into Belgium, they closed on their destination at 1000 hours the next morning.

In Bastogne, meanwhile, a fateful decision was being made. Division Surgeon Lt. Col. Gold met with the 101st’s Logistics Officer, Lt. Col. Carl W. Kohls, to select a site for the 326th Med’s clearing station. They chose a convenient road junction located about eight miles northwest of town on the Bastogne-Marche road, figuring this position was about as close to the rear area as could be expected. Neither officer seriously considered the possibility of an enemy breakthrough; information about German activity in the region was either inaccurate, out of date, or absent.

The 326th’s soldiers moved into their newly designated bivouac area and started setting up. Emil K. Natalle, a Technician 4th Class (T/4) with the 3rd Auxiliary Surgical Team, described this activity: “Soon after arrival, our tent crews hoisted the canvas, mess tent, headquarters tent, surgical tent, ward tents, the works.” Natalle also remembered hearing “…gunfire…to the east of us. Most of us had a hunch we were in vulnerable terrain…Our site was totally exposed, no cover, just open space.”

Aside from a single (and possibly unmanned) anti-tank gun pointing east down the road to Houffalize, the tent complex was completely undefended. In compliance with Geneva Convention rules regarding the noncombatant status of all medical personnel, no one there carried a personal weapon. The nearest infantry outpost, two miles distant, could offer little help in case of a sudden enemy attack.

Confusion reigned. Writing after the war, Major Crandall admitted, “We should have been more familiar with the current military situation.” Yet there was a job to do; at 1030 hours, teams of jeep ambulances set out to begin evacuating casualties from the regimental and battalion aid stations posted around Bastogne. Thirty minutes later, the clearing station admitted its first patient.

Sometime around noon, Lieutenant Colonel Gold and Major Barfield went on a reconnaissance to find an installation where the 326th Medical Company could transport its most urgent trauma cases. Near Libin, Belgium, they discovered both the 64th Medical Group’s headquarters and the 107th Evacuation Hospital. The commander there agreed to accept their casualties and even loaned out several field ambulances to supplement the 101st Airborne Division’s pool of litter jeeps.

A growing roar of gunfire, together with the sight of fleeing refugees, offered proof that a large-scale battle was taking place nearby. Some 326th Med soldiers observed that not every patient arriving at the clearing station that afternoon was wearing a Screaming Eagle shoulder patch. Several other outfits were bleeding themselves dry in order to buy time for the 101st Airborne to arrive, organize, and take over the defense of Bastogne.

Infantrymen and tankers from Combat Command B (CCB), 10th Armored Division, had since daybreak been grappling for possession of a hamlet named Noville, just a few miles northeast of town. This small task force, fighting alongside some American tank destroyers and, later, a battalion of McAuliffe’s paratroopers, managed to beat back several determined assaults—at a heavy cost.

Sometime that afternoon, German shellfire struck down both the parachute battalion commander, Lt. Col. James L. LaPrade, and the 10th Armored’s Major William R. Desobry inside their Noville command post. The barrage killed LaPrade outright and left Desobry with a grievous head wound. Rushed back to the 101st Airborne’s clearing station, Desobry underwent immediate emergency surgery. Sedated and with both eyes bandaged, he was then left in a ward tent to await evacuation.

It was becoming increasingly clear to combat-wise veterans such as McKee that no friendly forces stood between Noville and the 326th Medical Company’s tent hospital. “About 1600 hours,” he remembered, “I went into Division HQ and asked permission for us to move into Bastogne.” McKee further explained, “I thought we were in danger of being overrun,” adding that his division would be completely without advanced medical care if that were to happen.

The acting division commander, Brig. Gen. McAuliffe, did not want his clearing station to move just yet. Normally assigned as head of the Screaming Eagles’ division artillery, “Tony” McAuliffe found himself the senior 101st Airborne officer present when that organization was ordered forward into the Ardennes. He had just concluded a series of meetings with VIII Corps Commander Maj. Gen. Troy H. Middleton, whose last orders before leaving town were to “hold Bastogne.”

McAuliffe and his staff considered the situation confusing but manageable. Despite the loss of LaPrade and Desobry, their positions in Noville seemed to be hanging on for the time being. Elsewhere along the line, a garrison of nearly 22,000 paratroopers, glidermen, and armored infantry were hard at work establishing sturdy roadblocks intended to dominate key terrain. Stocks of ammunition, fuel, and rations seemed adequate, so long as routes to and from Allied supply dumps in the rear area remained open. To the 101st Airborne’s operations officers, it seemed highly unlikely that any enemy forces could encircle—let alone crush—the strongpoint style defense they were crafting.

Darkness fell early on the night of December 19. At 1630 hours, Major Barfield left the clearing station in charge of a convoy containing five ambulances and 15 wounded men. After delivering these casualties to the 107th Evac Hospital in Libin, Barfield found his route back to the crossroads blocked by dense fog and a blown bridge over the Ourthe River near Sprimont. Determined to try again after first light, the major turned his trucks around and headed back to Libin.

Meanwhile, ambulances from across the division continued to arrive at the clearing station. Separately, two regimental dentists —the 501st PIR’s Captain Carlous D. Lancaster and Captain Samuel Feiler of the 506th —led jeeploads of wounded soldiers back to the 326th Medical Company after sunset. Neither officer realized until it was too late that they were driving into an ambush.

Advancing through the murk was a column of German armored cars and halftracks from the 116th Panzer Division’s Reconnaissance Battalion. This unit, commanded by Major Eberhard Stephan, had been pushing forward through a rupture in the Americans’ lines for nearly three days. Stephan—a veteran of combat on both the Eastern and Western Fronts—spent the bulk of December 19 trying to find a suitable route around the fighting at Noville, through the recently abandoned village of Houffalize, and toward what he hoped would be still intact bridges across the Ourthe River north of Bastogne.

For the Ardennes campaign, Major Stephan’s thin-skinned scout cars were reinforced by at least six armored fighting vehicles (some sources list these as PzKpfw. V Panther medium tanks, while others suggest they were Sturmgeschutze III assault guns). Kampfgruppe (KG) Stephan’s column also included an artillery battalion, a Nebelwerfer (rocket launcher) battery, and several self-propelled antiaircraft guns.

So far, the 116th Panzer’s attack was going well. “The reconnaissance battalion dissipated and destroyed a number of enemy groups, knocked out some enemy tanks, [and] captured a lot of personnel and vehicles,” boasted Division Commander Maj. Gen. Siegfried von Waldenburg in a postwar interview. These German soldiers also appropriated large quantities of abandoned U.S. cold weather clothing, rations, and cargo trucks, a habit that would later lead Allied commanders to accuse Stephan’s men of intentionally concealing their identities by wearing enemy uniforms—a war crime.

Kampfgruppe Stephan departed Houffalize in mid-afternoon on December 19, its objective a bridge spanning the Ourthe at Salle, Belgium. To get there, the battlegroup needed to move five miles west down a secondary road and turn north at an intersection listed on German maps as the Bois de Herbaimont. At 2230 hours, Stephan’s advance guard came across a darkened tent camp adjacent to that crossroads. Gunners inside the lead vehicles immediately opened fire on their unsuspecting target.

First Lieutenant (Dr.) Gordon L. Block of the 326th Med was off duty “…sleeping not too peacefully in my hole that night” when the shooting started. Grabbing his steel helmet, Block crawled to the evacuation tent where “tracers tore through the canvas.” He remembered how “the wounded lying on stretchers groaned as some were hit a second time.” Aidmen risked death when they lowered screaming casualties to the ground and —in some cases—covered the wounded with their own bodies.

Captain McKee described how “a German motorized patrol…had knocked out the [anti-tank] gun at the crossroads” before setting alight six of the 326th Medical Company’s evacuation vehicles. Illuminated by the flames, Red Cross symbols adorning U.S. hospital tents now became visible to Stephan’s gunners. After a 15-minute shooting spree, they mercifully ceased fire.

According to McKee’s narrative, “Captain Charles Van Gorder, a member of the 3rd Auxiliary Surgical Team assigned to us—and of Pennsylvania Dutch origin, who spoke German rather well, yelled that we were medical troops and unarmed.” Lieutenant Colonel Gold quickly surrendered the facility to Major Stephan, who informed his new captives they had 30 minutes to load all their personnel and equipment into any functioning vehicles and follow his recon troops back to enemy lines.

While all this was taking place, several ambulances carrying injured G.I.s drove into the ambuscade. At the wheel of one jeep, Pfc. Robert Barger noticed “…a burning truck right there in the middle of the road.” Barger “…stopped at the top of the hill, trying to decide whether we should move down there or not,” when “a machine gun opened on us, killing the two litter cases” riding atop Barger’s vehicle. German soldiers then herded the stunned driver and his assistant into a nearby field where well over 100 newly captured prisoners of war sat glumly awaiting their fate.

Dentist Samuel Feiler’s ambulance team also blundered into KG Stephan’s ambush. Ordered by enemy troops to join the flock of POWs, Feiler surreptitiously tossed away a P-38 pistol that another officer had loaned him earlier. Then, noticing his captors were too busy looting the hospital to pay him much attention, Feiler kept on walking into the darkness until he reached safety.

One of Feiler’s medics, Pfc. Don M. Dobbins, witnessed another catastrophic incident when 12 cargo vehicles driven by African-American soldiers accidentally entered the kill zone. “The Germans fired on every truck standing there and set them on fire,” Dobbins wrote. “I remember a Negro truck driver in one of the trucks who got up in his cab and blasted away at the Germans with a 50-caliber gun mounted on his cab. He didn’t last long, for the Germans turned everything they had on him. If they had fired a second longer, they could have cut the cab away from the rest of the truck.”

A sergeant in 1st Lt. Henry Barnes’ evacuation platoon later claimed that Germans dressed in U.S. Military Police uniforms stopped his ambulance as it approached the Medical Company’s area. Just then, the luckless convoy of cargo vehicles appeared. “A machine gun started firing,” he said, relating how “a truck mushroomed up in smoke, with the canvas afire. Tracers were shooting out in all directions.” Eluding capture, Barnes’ sergeant later returned to the platoon command post with a look on his face that seemed “as though he had caught a brief glimpse of hell.”

“Down at the crossroads,” wrote T/4 Emil Natalle, “a number of vehicles were burning fiercely. Some of the vehicles surely had men inside, for we heard their cries for help.” Natalle, along with a German soldier, went to render aid but could not approach the scene due to intense heat.

“It was bedlam,” Natalle said of the onslaught. “The Germans were all over the area. They hollered, laughed, and made noise, just as Germans always do.” Caught up in their search for treasure, Major Stephan’s men inadvertently allowed several prisoners of war to escape. Both Sam Feiler and Don Dobbins slipped away into the night, as did three captains from the 326th Medical Company: Jacob Pearl, John Breiner, and Roy Moore.

Another airborne medic who evaded capture was Private Lester A. Smith. He and two other aidmen dashed off “…headed in the direction we thought we might find friendly troops.” After taking a short break to enjoy some food and drink offered by helpful Belgians, the trio approached U.S. lines around dawn. A sentry challenged them, and despite not knowing the password, Smith “convinced him we were American soldiers.”

A total of 11 officers and 119 enlisted men from the 326th Airborne Medical Company surrendered on December 19, 1944, along with four officers and three enlisted soldiers of the 3rd Auxiliary Surgical Group. Also taken prisoner were five men belonging to the Division Surgeon’s office, to include the 101st Airborne’s chief medical officer Dr. Gold.

One member of the 326th Med, Private Henry P. Sullivan, died from enemy fire, as did an unknown number of helpless casualties. No full identification has ever been made of the African-American truck drivers who stumbled into KG Stephan’s ambush; their unit and number of men killed on December 19, 1944, remain a mystery to this day.

In the early hours of December 20, a U.S. infantry patrol led by Captain Robert J. McDonald of Co. B, 401st GIR, cautiously approached the crossroads. One of these glidermen, 21-year-old Pfc. Carmen C. Gisi, recalled hearing a “loud, continuous wail” which was caused by the body of a dead truck driver draped over the horn of his vehicle. Gisi also observed in the gloom several careless German soldiers who were searching for souvenirs amid the clearing station’s wreckage.

McDonald’s riflemen swiftly formed on line and attacked the enemy stragglers. At dawn, after the Germans ran off, Gisi and his squad “went into the 326th Medical Company area where we found two troopers dead.” Word quickly passed up the chain of command to Brig. Gen. McAuliffe, confirming earlier reports of the hospital’s capture.

This was a troubling development for several reasons. Primarily, the Screaming Eagle Division now needed to constitute a new second echelon medical treatment facility from its already overworked regimental and battalion aid personnel. Even under ideal circumstances, it would be no easy task to replace the 142 highly skilled doctors and medics (not to mention their specialized equipment) lost in KG Stephan’s ambush.

The presence of enemy forces operating so deeply in what McAuliffe’s staff considered their rear area also caused American commanders to reconsider Bastogne’s safety. The 101st Airborne’s senior officers took a lesson from this unfortunate incident and started preparing a 360-degree strongpoint defense in case German troops and tanks encircled them.

That did in fact happen when enemy forces seized the last road into town at approximately 2330 hours on Thursday, December 21, 1944. Once again, Maj. Barfield (now promoted to the position of Division Surgeon) found himself unable to join his command as he had traveled outside the perimeter for a conference when Bastogne was surrounded. Barfield could not make his way back to the Screaming Eagles’ headquarters for nearly a week.

Within the besieged city, aidmen from the 501st PIR set up temporary collection facilities located inside a convent. To provide additional care for the casualties now accumulating in and around Bastogne, Major (Dr.) Martin C. Wisely of the 327th GIR assembled a team of physicians and medics from the 101st Airborne’s artillery, antiaircraft and attached tank destroyer units. Wisely opened an improvised clearing station at the Belgian Army barracks in town, later moving it into a basement garage after German forces began blasting their foe’s positions with heavy artillery and aerial bombs.

To ease the strain on Major Wisely’s facility, medics assigned to the 502nd PIR and CCB, 10th Armored Division, established their own ad hoc collecting posts. Unfortunately, CCB’s aid station was destroyed by a bomb on Christmas Eve. Killed in the explosion were a number of patients, as well as a Belgian woman who had volunteered to help nurse the wounded.

Shortages of whole blood, blankets, and penicillin constantly bedeviled Bastogne’s embattled aidmen as they attended to a growing number of wounded troops. Parachute resupply, which began on December 23, helped alleviate but never totally solved the problem. Luckily, the Screaming Eagles discovered in town several large medical stockpiles that had been abandoned by other outfits. Foraging parties also combed through ruined dwellings for quilts and bed coverings to help keep casualties warm.

A more serious challenge involved the garrison’s inability to conduct emergency surgery on those individuals most severely injured in battle. One trauma surgeon was flown into Bastogne by liaison plane on Christmas, while the following morning a CG-4A cargo glider carrying nine more medical officers and enlisted technicians landed inside the perimeter. This surgical team (assisted by three Belgian nurses) went to work immediately, performing major life saving operations on 50 patients over the next two days.

After Patton’s Third Army bulled its way into Bastogne on December 26, casualties could once again be evacuated. One day later, a convoy of 21 field ambulances and 10 cargo trucks carrying 260 patients rolled out of the formerly surrounded city. By December 28, all 964 wounded men trapped in the fighting there had been transported to higher echelon medical facilities.

The struggle for control of Bastogne continued well into the new year. In town, a provisional medical battalion took on the role of casualty collection while the 101st Airborne’s Division Surgeon, Major Barfield, worked to rebuild his clearing station. Captain Roy Moore took over command of the 326th Medical Company, devoting considerable time and effort in training the newly assigned aidmen sent forward to replace unit personnel lost in Belgium.

As difficult as Moore’s job was, it paled in comparison to the plight of those men taken prisoner on the night of December 19. Major Desobry, the 10th Armored Division officer wounded at Noville, woke up in the front seat of an ambulance headed east. Hearing German voices outside his vehicle, the temporarily-blinded Desobry said he must be traveling alongside a group of surrendered enemy soldiers. Desobry’s driver had to inform him that they were the ones being held captive.

The 326th Med’s Pfc. Henry S. “Hank” Skowronski walked into Germany, subsisting on rutabagas and sugar beets, until he arrived at Stalag IVB near Muhlberg. Skowronski also recalled how the food at Muhlberg, mostly “thin soup and bread that was baked with sawdust,” kept him and the 5,000 other POWs held there on the edge of starvation until Red Army forces liberated the camp in May 1945.

Like Skowronski, most members of the 326th Airborne Medical Company who survived KG Stephan’s surprise attack sat out the remainder of the war in a German POW camp. While behind the wire, they continued to care for their fellow captives with whatever supplies and medications were made available. Although the 101st Airborne Division no longer benefitted from their service, these dedicated doctors and aidmen undoubtedly kept alive many Allied prisoners of war during the last months of World War II.

Patrick J. Chaisson is a retired U.S. Army officer and historian who writes from his home in Scotia, New York.

Thanks for this article. Good insight into the logistics of medical care in very tough times. A different slant on that battle from what a reader normally sees in these articles. Well done Mr Chaisson.