By Blaine Taylor

Over 100,000 visitors annually trace with pride the footsteps of infantrymen from the 1607 wilderness of Virginia to the 1991 sands of the Persian Gulf and view weapons from the French Charleville flintlock musket to the atomic Davy Crockett mortar,” says the director of the National Infantry Museum, Z. Frank Hanner.

Established in 1959, the National Infantry Museum comprises 30,000 square feet of exhibit space in an impressive, historic masonry building with spacious, well-lit, carpeted galleries. The climate-controlled structure is wheelchair accessible and has an elevator serving three floors.

The first floor displays exhibits on early European infantry artifacts, as well as on the American Revolution. The second floor focuses on the history of U.S. infantrymen after the Revolution, when the infantry was called “The Sword of the Republic.” Following are displays on the War of 1812, the Mexican War of 1846-1848, and the peacetime Army during the pre-Civil War years of 1848-1860. The War Between the States is next, followed by exhibits on the American Indian Wars, Spanish-American War of 1898, Philippine Insurrection, Boxer Rebellion of 1900, Mexican Border Campaign of 1914-1916, and U.S. participation in World War I (1917-1918). These are followed by areas devoted to the U.S. infantry of the 1920s and 1930s and World War II in the Pacific.

The third floor exhibits begin with the World War II in Europe. They continue through the Korean War and the Army in the 1960s. Covered next is the Vietnam War, Operation Urgent Fury in Grenada (1983), and Operation Just Cause in Panama (1989). A display of weapons of the 1990s rounds out the third floor, and the visitor is directed back to the first floor for an exhibit of the 1990-1991 Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm.

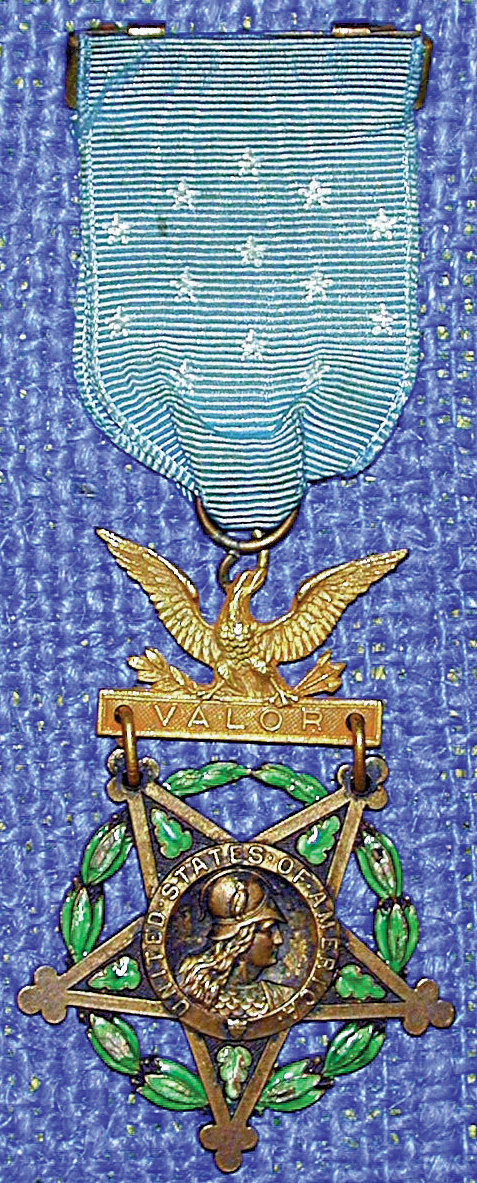

In addition, each of the trio of floors has special areas. On the first is the personal collection of five-star General of the Army Omar Bradley, as well as collections of Generals John T. Corley and William B. Rosson. There is a section on the history of Ft. Benning, one on three-time recipients of the Combat Infantryman’s Badge, and another on Medal of Honor awardee Captain Bobby Brown.

The second floor special area includes exhibits on Airborne troops and the Medal of Honor. The third floor has an Air Assault special weapons display.

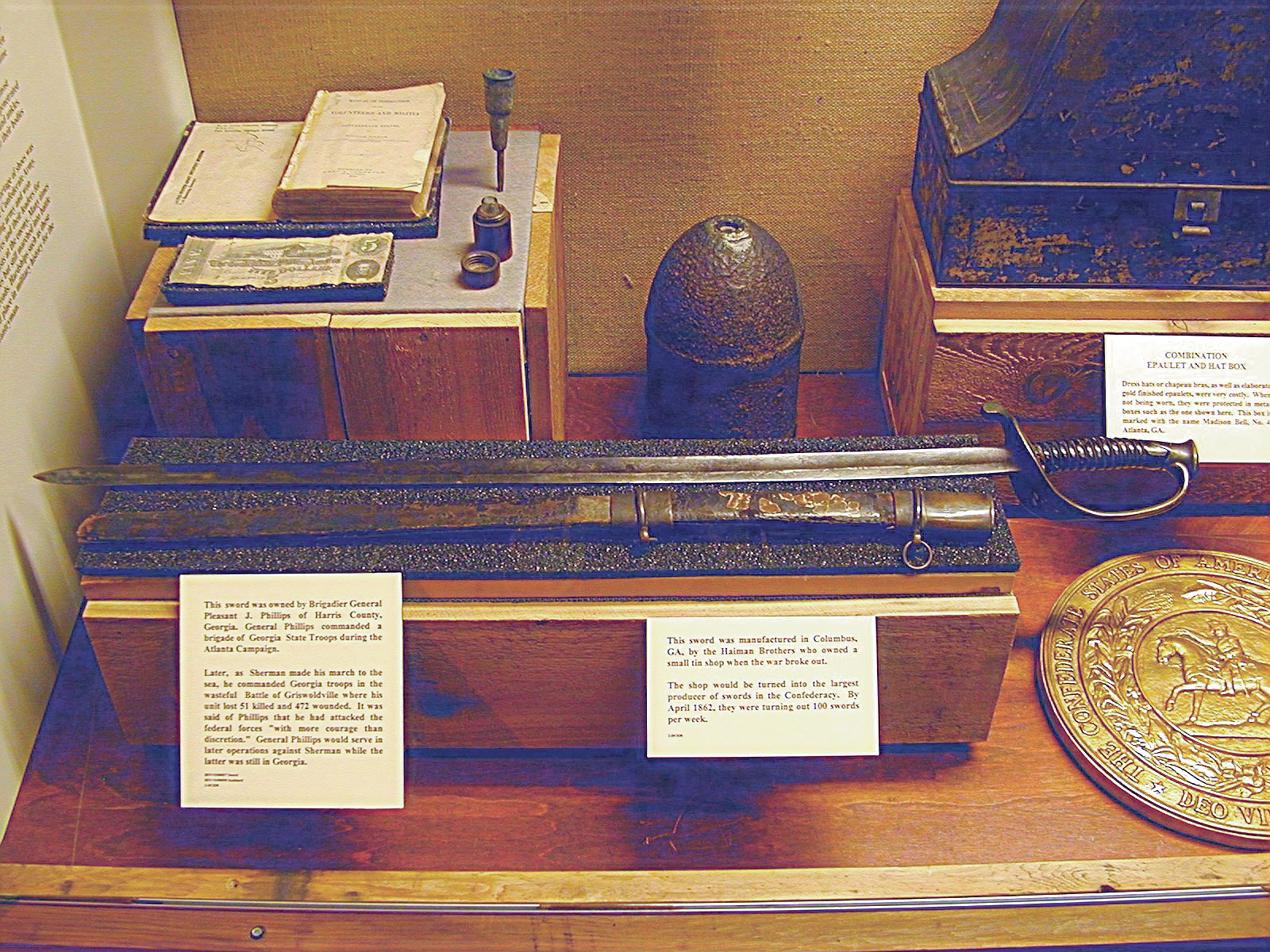

In addition, the museum exhibits some rather unusual and unexpected items. These include documents signed by Revolutionary War patriots John Hancock and George Washington, a World War I gas mask for a horse, a bust of Adolf Hitler, and Hermann Göring’s field marshal’s baton. In the museum are more than 1,500 firearms, including a 16th-century Spanish cannon, an early Japanese matchlock musket, and a Gatling gun. Also displayed are some uniforms and weapons of U.S. allies such as the British, and of U.S. enemies, such as Nazis. These last were sometimes captured in battle by U.S. infantrymen and, if so, their stories are told. Each display case has a lengthy and well-considered history of the period represented and descriptions of displayed items.

Says Hanner, “You might see an 1840 Chickering piano, a prisoner-of-war uniform, or—from the Civil War—dominos, playing cards, a painted eagle drum, or a bugle. The museum shows not only the weapons, uniforms, and personal equipment of U.S. infantrymen, but also those of enemies who chose to test our resolve.”

The grounds outside also have an impressive collection of armored vehicles. Here are examples of the U.S. M4A2 Sherman medium tank, a U.S. M47 Patton medium tank, a U.S. M114A1 Command and Reconnaissance Carrier, a U.S. XM723 Mechanized Infantry Combat Vehicle, and a U.S. M56 Self-Propelled Antitank Gun. There are also a number of Iraqi vehicles, including a T-72M1 medium battle tank.

A 100-seat auditorium shows a variety of documentary films daily, and a gallery of military art displays paintings, sketches, sterling silver, oriental pottery, and a collection of 19th-century newspapers. The gift shop offers art prints, books, pewter, and crystal as well as model soldiers, T-shirts, and jewelry.

The National Infantry Museum is located in Infantry Hall—or Building Four—of the Headquarters of the U.S. Army Infantry Center, the training school of the infantry. In front of the building stands the statue of “The Infantryman” in the classic “Follow Me” stance. It was commissioned in 1959 by the order of Lt. Gen. Paul L. Freeman, then the Commanding General of the U.S. Army Infantry Center.

An attempt to organize an “Infantry School of Instruction” began in 1826 at Jefferson Barracks, Mo., but the effort failed after two years. Decades passed and the Civil War ensued before a similar idea arose again. Noting the decline of good marksmanship in the Army, Civil War hero and Medal of Honor awardee Lt. Gen. Arthur MacArthur (father of five-star General of the Army Douglas MacArthur) helped establish the School of Musketry at the Presidio of Monterey, Calif., in 1907.

“This may be called the beginning of the present Infantry School, and the event that led to the creation of Ft. Benning,” says Hanner. “In 1913, the School of Musketry was transferred from the Presidio to Ft. Sill, Okla. With the outbreak of World War I and the need to expand the Army, Ft. Sill was not large enough for training both the infantry and the artillery. The Army needed a permanent Infantry School with adequate facilities for training the infantrymen who were to fight in France. The right geography and topography were essential. On May 21, 1918, a board was established with Colonel Henry E. Eames as president to recommend a site for the new Infantry School of Arms.”

Several locations were considered. Fayetteville, N.C., was the first choice, but was picked as an artillery site instead. The second choice was Columbus, Ga. According to Hanner, “On July 12, 1918, Majors Solomon and Gibbs of the Army’s Construction Division visited Columbus to select a building site for cantonments, or temporary-type structures, for about 30,000 officers and enlisted men.” By October 1918, the first troops occupied a temporary camp three miles east of town.

“At the request of the Columbus Rotary Club, the camp was named in honor of Confederate General Henry Lewis Benning,” says Hanner. “He was a Columbus native who was considered the most outstanding Civil War officer from the area.”

“The search for a permanent location for the camp settled on a plantation south of Columbus owned by Arthur Bussey,” continues Hanner. ”The Bussey land featured the kind of terrain considered ideal for training infantrymen. The plantation would serve as the core of the camp, and the large frame house, known as Riverside, would serve as quarters for a long line of commanders.”

Following years of struggle for appropriations and attention from Army policymakers, Camp (later renamed Fort) Benning experienced a construction boom in the mid-1930s as a result of the New Deal’s federal work projects. The building boom continued into the 1940s owing to the outbreak of World War II.

Says Hanner, “Troop strength swelled with the arrival of the 1st Infantry Division and the establishment of the Officer Candidate School (OCS) and Airborne training. During the ensuing years, Ft. Benning gradually emerged as the most influential Infantry Center in the world. Through the years, the mission of Ft. Benning has remained fundamentally the same: to produce the world’s finest combat infantrymen.”

The first class, which was from the U.S. Military Academy, graduated from the Infantry School on February 22, 1919. The first elements of the 29th Infantry Regiment arrived in March and still serve there today. Major Dwight D. Eisenhower brought the first tanks to the camp in January 1919. The first aviation unit—the 32nd Balloon Company—arrived in March 1920 and the camp was officially renamed Ft. Benning on February 8, 1922.

In January 1940, the first U.S. Army antitank battalion was activated at Ft. Benning, and the following June the first U.S. Army Parachute Test Platoon asked for volunteers from the 29th Infantry Regiment so that a paratroop unit could be established. Two months later the platoon made its first test jump.

“On October 15, 1940, the U.S. Army established the 1st Parachute Battalion at Ft. Benning,” says Hanner. “Later it was designated the 501st Parachute Infantry Battalion and it would produce more general officers than any other battalion in our military history.”

On July 5, 1941, the first officer candidates arrived at OCS for training. The first African-American parachute unit—the 555th Parachute Infantry Company—was activated in January 1944.

The Ranger Training Command was established at the fort in 1950 to train Airborne Ranger companies to fight in the Korean War. In August 1952, the first OCS class graduated since the end of World War II.

In1962, during the Kennedy Administration and for the first time in military history, an Air Assault Division—the 11th—was activated to test and further develop the use of helicopters to support infantry ground operations, a stratagem used throughout the Vietnam War and up to the present day. In June 1963, the CH-54A “Flying Crane” was field-tested at Ft. Benning for the first time by the 11th. In July 1965, the 11th was redesignated the 1st Air Cavalry Division (Airmobile) and was soon sent to Vietnam.

In 1986, the army made Ft. Benning the permanent site of the U.S. Army School of the Americas. Officers from all over Latin America have come here to train.

Today, Ft. Benning continues in its task to create the best infantry in the world. And it honors its National Infantry Museum, which ably tells the noble story of the triumphs and sacrifices of American soldiers who fought in their nation’s service.

Admission to the National Infantry Museum is free. It is open to the public Monday through Friday from 10 am to 4:30 pm, and on Saturday and Sunday from 12:30 to 4:30 pm. The museum is closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas, and New Year’s Day and, when federal holidays are celebrated, on Mondays. The museum is easily accessible by car from I-185, and there is ample free parking. Tours may be arranged by calling (706) 545-2958. For other information, call (706) 545-6762. The Web site is www. infantry.army.mil/museum.

Towson, MD, freelancer Blaine Taylor is the author of a trio of books on World War II. He trained at the Infantry School as an Officer Candidate in 1966 and was awarded the Combat Infantry Badge with the U.S. Army 199th Light Infantry Brigade in South Vietnam during 1966-1967.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments