By Kevin M. O’Beirne

The Chancellorsville campaign has been called many things, from “a stupendous defeat” for the curiously cautious “Fighting Joe” Hooker, to Robert E. Lee’s “greatest victory.” The campaign was exceedingly complex and some of its students tend to focus on its more romanticized aspects: the aggressive Lee dividing his army twice in the face of an enemy that outnumbered him more than two to one; Stonewall Jackson’s famous flank attack on XI Corps, Hooker’s alleged drunkenness (never proven); and Hooker being knocked senseless on May 3, thus depriving the Union army of leadership for several crucial hours at the height of the battle.

In reality, the outcome of the battle of Chancellorsville hinged more on some lesser-known points of near-flawless generalship, and many abysmal blunders on both sides. Some of the most interesting are:

Near-Perfect Generalship

Hooker’s planning of the campaign was excellent. He crafted in complete secrecy a complex plan that was carried out to the letter, at least in the campaign’s early stages. Hooker’s masterful preparations provided him with exact knowledge of the numbers and disposition of Robert E. Lee’s army on the eve of the campaign, while Lee knew practically nothing of Hooker’s plans.

Lee and Stonewall Jackson were apprised by local residents loyal to the Confederate cause that Hooker’s right flank was highly vulnerable to attack. The Rebels exploited this advantage to the utmost.

Lee received yeoman’s service in the campaign by his senior commanders, most notably Stonewall Jackson, J.E.B. Stuart, and Jubal Early. In particular, Early kept a Union force several times the size of his own 10,000-man division occupied for several days.

Blunders at Chancellorsville

Due to a severe supply problem in the winter of 1862-1863, General Lee had to disperse substantial portions of his army. Among these were the veteran divisions of John Bell Hood and George Pickett which, together with their corps commander, Lt. Gen. James Longstreet, were sent to forage in southeastern Virginia. Lee approved Longstreet’s plan to attack the Federal garrison at Suffolk, 120 miles from Lee’s army. The Suffolk campaign turned into a siege that lasted for nearly a month, and was still in progress when Hooker initiated the Chancellorsville campaign. Longstreet’s 12,000 men could have drastically altered the outcome of the battle of Chancellorsville had they been available to Lee.

Hooker planned himself right out of the services of his large, new cavalry corps. Anticipating that his infantry would rout Lee, “Fighting Joe” detailed the Union cavalry to ride behind the Confederates to disrupt their communications and block their retreat. The cavalry failed miserably in this mission and deprived Hooker of their valuable scouting capability. A good cavalry screen might well have prevented Jackson’s flank attack on May 2.

Lee and his famous cavalry commander, J.E.B. Stuart, can be faulted for slipshod disposition of Confederate cavalry pickets at the upper fords along the Rappahannock and Rapidan Rivers. The almost-unguarded fords allowed Hooker to get his army into position and nearly overwhelm Lee at the start of the campaign.

Hooker probably planned to concentrate his army and then entice Lee into a suicidal attack. However, when Hooker withdrew his army to Chancellorsville on May 1, he committed the fatal blunder of allowing Lee to seize the initiative.

While Hooker securely anchored his eastern flank on the Rappahannock River, he chose his least reliable corps to guard his exposed western flank, which is exactly where Jackson hit the Federals at dusk on May 2.

Jackson’s flanking column took an entire day to march 10 miles and get into position on the Federal right flank. The long column was spied by many Union soldiers and officers; their reports were relayed up the chain of command where, incredibly, they were interpreted as a Rebel retreat.

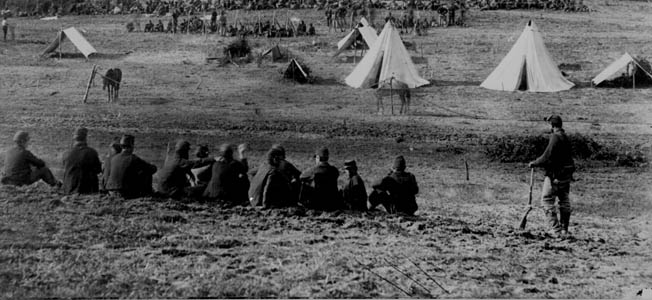

Capturing The Regiment

Believing Lee to be in retreat, the Union III Corps, led by Daniel Sickles, chased after the Confederates during the afternoon of May 2 and succeeded in catching only the tail-end of Jackson’s column. This move resulted in the capture of a single gray-clad regiment, and temporarily deprived Hooker of over 10,000 veteran troops who would otherwise have been in a good position to backstop the panicked XI Corps once Jackson’s attack was launched.

Believing himself cut off from the rest of the Union Army during the night of May 2, Sickles launched an unauthorized midnight bayonet charge—the main result of which was to attack troops of his own army.

Hooker permitted Sickles to withdraw from Hazel Grove at dawn on May 3. One of the few cleared high points in the Wilderness, Hazel Grove was vitally important and was yielded to the Confederates without a struggle. The Rebels quickly positioned artillery at Hazel Grove that wreaked havoc on the Federal defenses at Fairview and Chancellorsville.

On May 3, Robert E. Lee forced Hooker’s main body to retreat from Chancellorsville. The following day, the Confederates left a very thin covering force to occupy Hooker’s host, while the main part of Lee’s army moved southeast to rout Sedgwick’s Federal VI Corps at Salem Church and Banks Ford. While the outnumbered VI Corps fought for its life alone, Hooker did nothing to come to its aid, erroneously believing he was confronted by superior numbers of aggressive enemy troops.

Lee can be faulted for employing the tactical offensive throughout the campaign. Chancellorsville is often touted as “Lee’s greatest victory,” but the Pyrrhic “victory” cost the Army of Northern Virginia 13,000 valuable men plus the irreplaceable Stonewall Jackson, who was mortally wounded on May 2. At the price of nearly a quarter of his army, Lee succeeded only in blunting the Yankee offensive and driving the bluecoats back literally a few miles into their old camps. The 13,000 Confederate soldiers lost at Chancellorsville could well have turned the tide of battle two months later at Gettysburg, possibly altering the outcome of the war. Could Lee have checked Hooker by remaining on the defensive, as he did against Grant a year later?

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments