By Mason B. Webb

For over 60 years, the popular misconception in the West is that the U.S. and Great Britain carried the burden of World War II, while the Soviet Union played a supporting role. Two recent books—No Simple Victory and The Greatest Battle—turn that notion on its head. It was the Soviet Union, say these authors convincingly, that carried the heavy end of the stick, while the U.S. and Britain made significant but much smaller contributions.

In No Simple Victory (Viking Press, New York, 2007, 544 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $30.00), an intentionally contrary treatise, the eminent British historian Norman Davies cuts against the grain and deconstructs the old notion that it was the West, with a little help from Joe Stalin and the Russians, that won the war. In his powerful and persuasive argument, Davies explains how the West’s misconceptions were built in the first place and presents a detailed account of the ways in which the war has been portrayed in film, art, and literature, and how these images have subsequently altered public perception.

In No Simple Victory (Viking Press, New York, 2007, 544 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, $30.00), an intentionally contrary treatise, the eminent British historian Norman Davies cuts against the grain and deconstructs the old notion that it was the West, with a little help from Joe Stalin and the Russians, that won the war. In his powerful and persuasive argument, Davies explains how the West’s misconceptions were built in the first place and presents a detailed account of the ways in which the war has been portrayed in film, art, and literature, and how these images have subsequently altered public perception.

Much of the current thinking, Davis explains, has a great deal to do with the anti-Soviet, anti-Communist sentiment that was prevalent in the West during and following the war, as well as a paucity of reliable information released from behind the “Iron Curtain.”

As Davies writes, “In the case of the Soviet Union, a significant discrepancy arose between the huge influence of Marxist-Leninist theory on Western historians and the tiny trickle of credible information about Soviet realities. A whole generation of British, French, and American historians, deeply affected by the war, began publishing before it was over. But sober studies about Stalin and Stalin’s policies had to wait for decades.”

Davies asks readers to reconsider what they already believe about World War II and how those beliefs might be biased or even incorrect. He points out, for example, that the seven biggest land battles of the war were all fought on the German-Russian front; major battles in the West, such as the Normandy invasion and the Battle of the Bulge were—in terms of numbers of troops involved and casualties incurred—minor skirmishes compared to the immense struggles in the East.

Through a very thorough exploration of long-buried facts, particularly focusing on the role of the U.S.S.R. and the Red Army in the defeat of Nazi Germany, Davies proves that the contribution of the Soviet Army was far more significant than previously portrayed in the West, and that the war, far from being a contest between good and evil, was, at least on the Eastern Front, a contest between twin evils.

The Greatest Battle: Stalin, Hitler, and the Desperate Struggle for Moscow That Changed the Course of World War II, by Andrew Nagorski, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2007, 366 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $27.00.

Waged by seven million troops—with 2.5 million killed, wounded, or taken prisoner—the battle for Moscow was the largest battle between two armies in history. What should be one of the best known battles has been reduced to obscurity, especially in the West, but also in Russia.

Although enormous in scale and importance, the battle for Moscow never quite achieved the supreme heroic status that Stalin accorded to the victories at Stalingrad and Kursk. It was downplayed in official Soviet histories because it was marred by too many errors and miscalculations by Stalin. Andrew Nagorski, formerly Newsweek’s Moscow bureau chief, has taken it upon himself to set the record straight and give this titanic struggle its proper due.

Nagorski cites the many early Soviet failures and miscalculations—Stalin’s naïve belief that the nonaggression pact he had signed with Hitler would be honored, the lack of trained officers following Stalin’s purge of the officer corps, and the throwing of ill-prepared and ill-equipped troops into the breach. The author also examines the political as well as the tactical decisions made by both leaders—Stalin’s decision to remain in Moscow during the siege, which rallied the Russians to him, and Hitler’s decision to disregard his generals’ advice and pursue his own grandiose but wrong-headed schemes that would lead to disaster.

In bringing this remarkable account of the battle to life, Nagorski draws on official records, visits to battlefields, and interviews with surviving soldiers and others who witnessed the events—from massacres in small villages to the near-famine and other calamities in the besieged capital.

Nagorski points out that the truth behind the battle for Moscow “is completely at odds with the standard image of Stalin’s Soviet Union and its propaganda line about the unflinching unity and heroism of its people at their moment of greatest peril. So Soviet history books have generally whitewashed what happened.”

As Nagorski concludes, “Moscow’s defenders paid a horrific price, but they changed the course of history, not just for their own country but also for everyone locked in the struggle against Hitler’s Germany.” Nagorski’s book makes a fine companion piece to the Davies’ study. Both are highly recommended.

Betrayal: The True Story of J. Edgar Hoover and the Nazi Saboteurs Captured During WWII, by David Alan Johnson, Hippocrene Books, New York, 2007, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

Betrayal: The True Story of J. Edgar Hoover and the Nazi Saboteurs Captured During WWII, by David Alan Johnson, Hippocrene Books, New York, 2007, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.95.

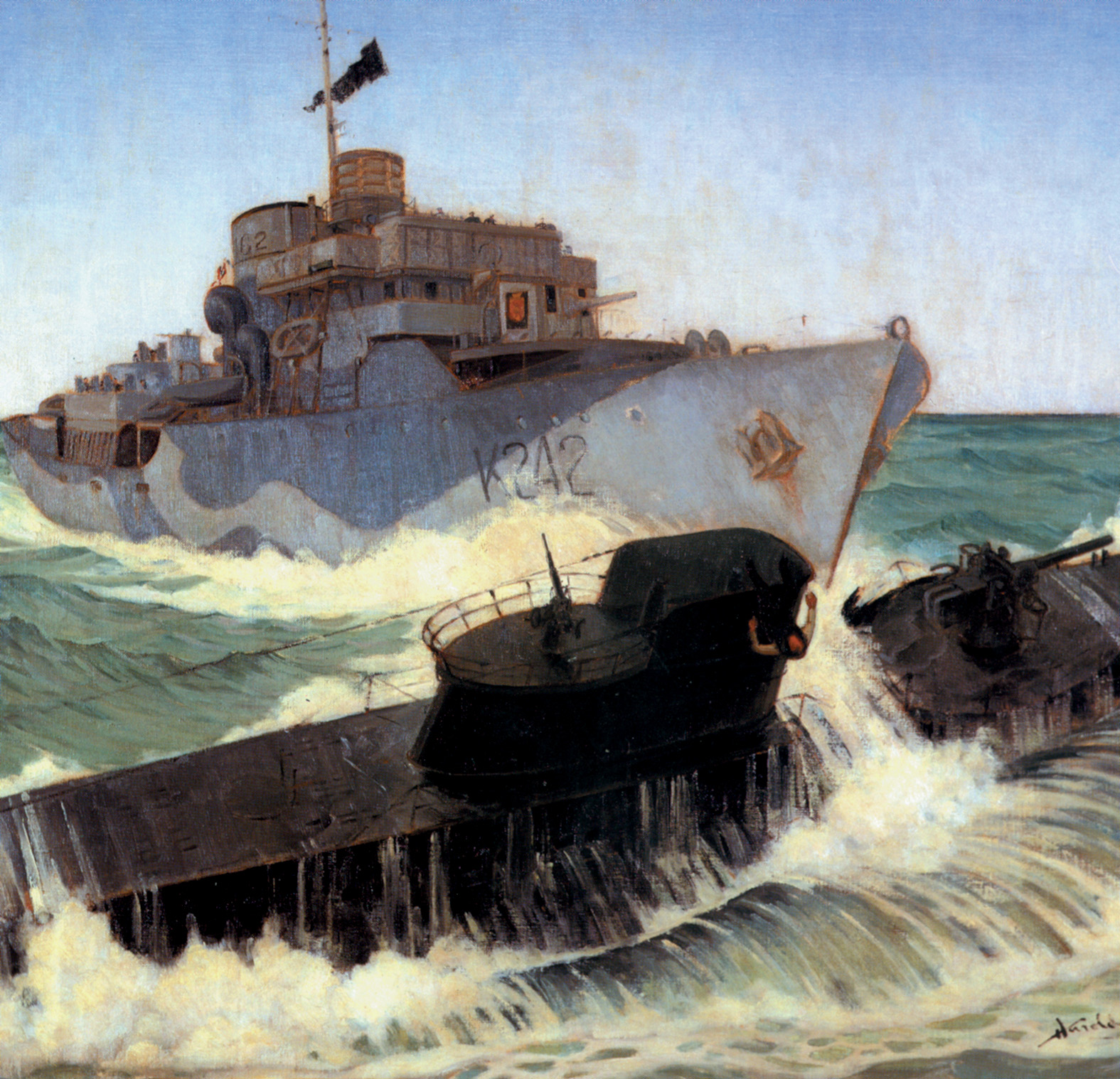

Before dawn on the foggy morning of June 12, 1942, a German submarine discharged its four passengers in an inflatable raft along the coast of New York’s Long Island. The four passengers, all dressed in civilian clothes, had come to America ostensibly on a mission of sabotage—Operation Pastorius—to blow up key factories manufacturing vital war material.

What the Nazis who sent the saboteurs to the U.S. did not know was that the leader of the four-man team, George Dasch, was bent on sabotaging the sabotage operation. Dasch was a German citizen who had come to America before the war, married an American girl, but was persuaded to return to Germany by his mother, and was then unable to get back to the U.S. when war broke out.

Dasch loved America and hated the Nazis. When he was recruited by the Gestapo to take part in the operation, he felt he could accomplish two things: return to the U.S. and throw a monkey wrench into Germany’s plans to wreck American industry.

Naïvely thinking that he would be welcomed back to his adopted country as a patriot after he and his team landed, Dasch went straight to the FBI to turn himself in. He did not count on egomaniacal FBI chief J. Edgar Hoover wanting to discount Dasch’s role in the foiled plot so he could take all the credit for breaking up the sabotage effort himself. Instead of being hailed as a Nazi-fighting hero, Dasch and his co-conspirators found themselves on trial for their lives in front of a military tribunal.

In this fast-paced book that reads like a spy novel, Johnson shows step by step how George Dasch’s sincere desire to aid his adopted country began to unravel as soon as he contacted the FBI, and how his faith in American justice and fair play was shattered. A most interesting and thought-provoking book.

Sinking the Rising Sun: Dog Fighting and Dive Bombing in World War II, by William E. Davis, Zenith Press, Bath, United Kingdom, 2007, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $26.95.

Sinking the Rising Sun: Dog Fighting and Dive Bombing in World War II, by William E. Davis, Zenith Press, Bath, United Kingdom, 2007, 304 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $26.95.

“In theory, I shouldn’t have been able to see the tracers coming toward me, but I could see them coming up very clearly,” writes William Davis. “They appeared to be climbing slowly toward me in an arc, like a soft lob in tennis, then suddenly they’d flash past me to explode behind my plane. The gunner hadn’t led me enough. Now the shells were further in front, and I knew immediately it was going to be close.”

William E. Davis III, a naval aviator with Torpedo Squadron 19, based aboard the aircraft carrier USS Lexington, has crafted an excellent autobiography, Sinking the Rising Sun, one of the most heart-pounding recollections of aerial battle ever written. Davis was awarded the Navy Cross after displaying extraordinary heroism during the furious Battle of Cape Engaño in October 1944. Bravely flying through sheets of enemy fire, Davis was able to place a bomb on the flight deck of the Japanese carrier Zuikaku, which eventually sank.

Recreating the life-and-death drama of dogfighting and dive bombing over the Pacific, Davis recounts how his squadron shot down 155 enemy planes while losing only two of its own. More than a just book about his many aerial combat experiences, Davis has also written a fine account of how he was trained, how he and his fun-loving mates raised hell at parties in Hawaii, how he and the aviators aboard the Lexington lived between missions, and how death over the vast ocean could come swiftly and unexpectedly.

Sinking the Rising Sun is a rare, true life account of what it was like to be in the cockpit of the powerful F6F Hellcat during some of the key battles of the Pacific Theater. Don’t miss this one.

The Last Ditch: Britain’s Secret Resistance and the Nazi Invasion Plan, by David Lampe, Greenhill Books, London, 2007, 220 pp., photographs, maps, index, hardcover, $34.95.

The Last Ditch: Britain’s Secret Resistance and the Nazi Invasion Plan, by David Lampe, Greenhill Books, London, 2007, 220 pp., photographs, maps, index, hardcover, $34.95.

Novelists, playwrights, filmmakers, and historical theorists have often played with the question of what would have happened had the Germans invaded Britain in 1940. The answer to this question is contained in David Lampe’s book. Originally published in 1968, The Last Ditch is a compelling study of exactly what was intended by both sides. Methodically investigating the German invasion and occupation plans, then detailing the countermeasures that were to be undertaken by the British Resistance Organization, a guerrilla-warfare group, Lampe presents a realistic scenario of harsh occupation and fierce resistance.

The author shows how the British were trained to spy, sabotage, and kill. Hideouts were established, caches of arms and explosives were hidden, and a resistance radio network was established. For their part, the Germans would have acted every bit as cruelly as they did following their invasions of Poland, Czechoslovakia, France, the Low Countries, the Soviet Union, and elsewhere.

Although the invasion of Britain never took place, the resistance was ready and waiting. So successful was the organization that it became the model for underground movements all over occupied Europe.

The Last Ditch is a chilling, “what if” look at what both sides would have faced had the invasion gone ahead as planned.

The Luftwaffe Over Germany: Defense of the Reich, by Donald Caldwell and Richard Muller, Greenhill Books, London, 2007, 304 pages, photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

The Luftwaffe Over Germany: Defense of the Reich, by Donald Caldwell and Richard Muller, Greenhill Books, London, 2007, 304 pages, photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

On September 4, 1939, the first British bombs fell on a fleet of German warships. So began British aerial retaliation for Germany’s invasion of Poland. Over the next six years, the aerial assault—first by Britain alone and then with the addition of the U.S. Eighth Air Force—would grow in intensity and destructive power.

Yet, despite the thousands of raids and millions of tons of bombs, the Germans managed to hold out, thanks in large part to the pilots of the fighter aircraft of Hermann Göring’s Luftwaffe.

At first a formidable force, the Luftwaffe was gradually reduced through attrition to a shadow of its former self, barely able to challenge the huge Allied bomber formations.

Caldwell and Muller, two noted Luftwaffe historians, have put together a remarkable book that documents the history of the German air force from beginning to end. Working on the project for over 10 years, the authors have delved deeply into logbooks, doctrine manuals, after-action reports, war diaries, official records, and interviews with surviving Luftwaffe veterans to bring this amazing story to life.

The result is a full and fabulous history of the Luftwaffe’s fighter arm—the Fw-190s, Bf-109s, and Me-262s—that battled the Allied bomber streams. In this richly illustrated volume with over 200 photos, the authors present a complete examination of Luftwaffe organization, theory, and doctrine that eventually affected Germany’s ability to defend itself.

This is a meticulously researched history of the longest and most intensely fought air battles of all time, worthy of a place on any aviation buff’s bookshelf.

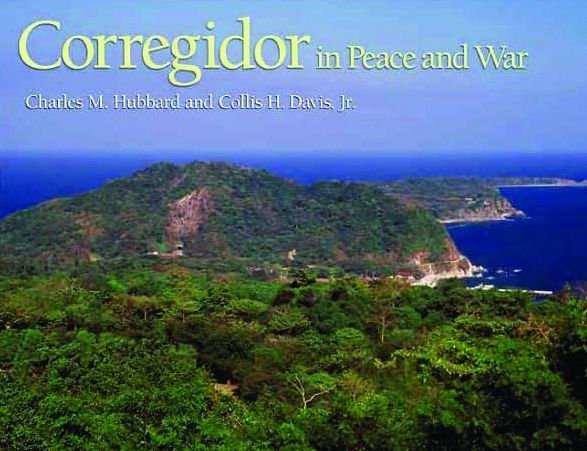

Corregidor in Peace and War, by Charles M. Hubbard and Collis H. Davis, Jr., University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2007, 198 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

Corregidor in Peace and War, by Charles M. Hubbard and Collis H. Davis, Jr., University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2007, 198 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

Since the days of Magellan and the Spanish galleons, the island of Corregidor, guarding the entrance to Manila Bay, has played an important role in the history of the Philippines, the Far East, the South China Sea, and the Pacific Ocean.

During World War II, Corregidor’s defiant stand against Japanese invasion, its role as the heartbeat of General Douglas MacArthur’s doomed defense of the Philippines, and its eventual capture by the Japanese on May 6, 1942, have all been well documented in numerous histories.

Less well known, however, is the rest of Corregidor’s story; Hubbard and Davis’s heavily illustrated volume fills in the sizeable gaps in our knowledge. The authors detail the island’s transformation from a sleepy tropical rock into an important, formidable fortress captured by the U.S. during the Spanish-American War and continuously improved until 1941.

Interweaving old and new photos (many in color) with informative text, the authors provide a guided tour of the fortified island that captures the natural beauty of the site. Brilliant color images evoke a place where flora and wildlife coexist alongside abandoned fortifications, battered casemates, skeletal barracks, and scarred artillery pieces.

Today a tourist destination as well as a significant historical monument, Corregidor remains a beautiful, haunting island—and Corregidor in Peace and War is an outstanding tribute to the myths, legends, and heritage of the site.

Rommel’s Lieutenants: The Men Who Served the Desert Fox, France, 1940, by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2007, 202 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

Rommel’s Lieutenants: The Men Who Served the Desert Fox, France, 1940, by Samuel W. Mitcham, Jr., Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2007, 202 pp., photographs, maps, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

One of the ablest and most admired of the German commanders was Field Marshal Erwin Rommel. Much has been written about his role as commander of the Afrika Korps where, outmanned by the British, he nevertheless out-dueled his opponents on several occasions and earned the sobriquet “the Desert Fox.”

Less has been written about his service as commander of the 7th Panzer Division—the so-called “Ghost Division”—during the lightning advance into France in 1940. During this campaign, 7th Panzer, although suffering more casualties than any other German division, inflicted even greater damage on the enemy divisions in its path, taking nearly 100,000 prisoners and capturing huge numbers of tanks, trucks, and guns. It was after spearheading this blitzkrieg that Rommel was selected by Hitler to take charge of German forces in North Africa.

But 7th Panzer was not a one-man show; Rommel had a great deal of help in France. His staff officers and regimental, battalion, and company commanders were an extremely capable collection of military leaders that included twelve future generals. Until now, no book has focused on the careers and contributions of Rommel’s “lieutenants,” men such as Hans von Luck, Frido von Senger und Etterlin, Karl Hanke, Gottfried Froelich, Rudolf Sieckenius, and many others. Mitcham’s carefully researched and extremely well-written book brings to light these leaders and their important contributions in the early German victories.

Short Bursts

P-47 Thunderbolt at War, by Cory Graff, Zenith Press, Bath, United Kingdom, 2007, 128 pages, photographs, illustrations, technical drawings, bibliography, index, softcover, $19.95.

P-47 Thunderbolt at War, by Cory Graff, Zenith Press, Bath, United Kingdom, 2007, 128 pages, photographs, illustrations, technical drawings, bibliography, index, softcover, $19.95.

Regarded by many as the most significant aerial combatant of World War II, the Republic P-47 Thunderbolt (nicknamed the “Jug”) was the largest and most powerful single-engine aircraft of the war. And with over 15,000 P-47s built, its production numbers topped those of any other American fighter.

P-47 Thunderbolt at War traces the history of this tough warplane—from its design, prototype, and testing to its employment in all the major theaters of the war. Whether used as air superiority fighters, protective escorts for fleets of bombers, or as tactical fighter bombers, the P-47’s speed, firepower, and durability made it a mainstay of American aerial combat.

Over 100 color and black-and-white photos bring the complete story of this legendary warbird to life.

FUBAR: Soldier Slang of World War II, by Gordon L. Rottman, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2007, 296 pp., illustrations, bibliography, hardcover, $15.95.

FUBAR: Soldier Slang of World War II, by Gordon L. Rottman, Osprey, Oxford, United Kingdom, 2007, 296 pp., illustrations, bibliography, hardcover, $15.95.

“Military slang is as old as warfare,” says author Gordon L. Rottman. He points out that soldiers “develop their own, far earthier, terminology covering all aspects of their lives. Words, nicknames, acronyms, abbreviations, and phrases are bestowed on all manner of things, often with a cynical, humorous or completely profane twist.”

He goes on to prove his point with chapters devoted to U.S. Army and Marine Corps slang, Tommy-Aussie-Canuck-and-Kiwi talk, and even German, Japanese, and Soviet soldier speak. If you know the meaning of “collision mats,” “prang,” “clifty wallah,” “orgurtsy,” “kojiki bukuro,” and “Nachthexen,” you’re either a World War II veteran or you already read the book.

FUBAR is a fun, informative look at language that is guaranteed to provide hours of enjoyable information.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments