By Mason B. Webb

When does war end and slaughter begin?

That is the question that drives this compelling reexamination of the Allied aerial bombing campaign against Germany during World War II.

From 1942 to 1945, American and British bomber forces dropped nearly two million tons of bombs on Germany, destroying some 60 cities, killing more than 600,000 citizens, and leaving 80,000 Allied air crewmen dead.

During the past 60 years, books written by American authors have tended to focus on the bravery of the American bomber crews, facing flak and fighters to burn out the heart of the Third Reich, while minimizing the suffering of German civilians, Recently, however, historians have taken another view. Several books about the devastating raids on Dresden have cast a new light on the bombing campaign, arguing that perhaps these raids should be seen as war crimes perpetrated by the Allies against innocent men, women, and children. Randall Hansen’s book Fire and Fury: The Allied Bombing of Germany, 1942-1945 (NAL Caliber, New York, 2009, 352 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $25.95) raises this disturbing question anew.

While not completely absolving the Americans of responsibility, he reserves most of his criticism for Sir Arthur “Bomber” Harris, the British head of Bomber Command and the architect of massive retaliatory raids against Germany.

The terrible truth in this scathing indictment of Harris and Bomber Command is that most of the British “area” bombing was carried out against the expressed demands of the Allied military leadership, leading to the needless deaths of hundreds of thousands of civilians, the wanton destruction of scores of beautiful medieval and Baroque cities, and the prolonging of the war.

By contrast, American precision bombing almost brought Nazi Germany to its knees. Throughout the war, writes Hansen, a University of Toronto political science professor, the United States did its utmost to minimize civilian casualties, trying its best to target primarily industrial sites, transportation networks, and troop concentrations in order to seriously restrict Hitler’s ability to wage war.

America’s fusion of determination, optimism, and morality, says Hansen, played an integral and largely unrecognized role in securing Allied victory in the skies over Europe.

This book is a thoughtful, well-written, and brilliant, if disturbing, analysis of the British and American air campaign that ultimately reminds us of the basic idealism and principles that underpin the history of American military power. Highly recommended.

The Battle of the Bulge: The Photographic History of an American Triumph, by John R. Bruning, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $50.00.

The Battle of the Bulge: The Photographic History of an American Triumph, by John R. Bruning, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 288 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $50.00.

Fought six and a half decades ago, the Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last-gasp major offensive to stave off defeat in the West, still ranks as the largest single battle ever fought by the United States Army. More men, vehicles, aircraft, equipment, and effort took part in this 36-day battle than any other in American history.

Thirty-one American infantry and armor divisions––fully one third of all the U.S. Army divisions formed during World War II––saw action during this titanic struggle in the hilly, heavily wooded, and snow-clogged Ardennes region of Belgium and Luxembourg. Not only were American soldiers, green troops, and veterans alike thrust into an unexpected battle in unimaginably harsh weather conditions, but they also faced some of the best and most battle-hardened troops Nazi Germany had left.

The story of the Bulge, as author Bruning tells it in this stunning, lavishly illustrated new work, is the story of panic, fear, and physical misery, as well as sheer courage and determination in the face of overwhelming odds.

Bruning’s book is arguably the most complete and awe-inspiring history yet published about this epic battle. The text and 500 photos (many of which were previously unpublished) place the reader in the frozen, snow-filled foxholes, the dark, haunting forests, and the devastated towns and villages of the Ardennes during the brutal winter of 1944-1945 like no previous book on the subject has.

The author’s well-written text includes much insightful detail, replaying the thrusts and volleys of both the Allied and German forces during the tumultuous, ever-changing battle.

It is a fitting tribute to the men who braved the weather and the relentless enemy to snatch victory from the jaws of defeat. Highly recommended.

D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, by Antony Beevor, Viking Press, New York, 2009, 592 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $31.95.

D-Day: The Battle for Normandy, by Antony Beevor, Viking Press, New York, 2009, 592 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $31.95.

From the acclaimed author of Stalingrad and The Fall of Berlin 1945 comes the first major book since Stephen E. Ambrose’s D-Day: 6 June 1944 to cover all the aspects of the monumental Operation Overlord, from the landings in early June to the liberation of Paris more than two months later.

Basing his work on research done in more than 30 archives in six countries, Beevor uncovered new material not published in previous books. The result is a work of extreme depth and complexity.

In discussing the Allies’ pre-invasion jitters and second-guessing, Beevor notes, “Eisenhower was far from being the only one awed by the enormity of what they were launching. Churchill, who had always been dubious about the whole plan of a cross-Channel invasion, was now working himself up into a nervous state of irrational optimism, while Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke [the pessimistic Chief of Britain’s Imperial General Staff and never an Eisenhower fan] confided to his diary that there was ‘an empty feeling at the pit of one’s stomach. It is very hard to believe that in a few hours the cross-Channel invasion starts! I am very uneasy about the whole operation. At best it will fall so very far short of the expectation of the bulk of the people, namely all those who know nothing of its difficulties. At worst it may well be the most ghastly disaster of the whole war.’’’

While Beevor covers much familiar ground, he also details a largely unknown part of the operation that most other historians have overlooked: the heavy casualties suffered by the French population. In fact, as he points out, more French civilians were killed by Allied bombing and shelling than British civilians died as a result of Luftwaffe attacks during all the months of the Blitz.

For anyone who wants to understand the entire operation, complete with its myriad successes and failures, it will be hard to find a book that beats this one.

War Stories of D-Day: Operation Overlord — June 6, 1944, by Michael Green and James D. Brown, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 312 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $28.00.

War Stories of D-Day: Operation Overlord — June 6, 1944, by Michael Green and James D. Brown, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 312 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $28.00.

As a companion piece to Beevor’s broad- ranging work is this compilation of first-person stories of D-Day as told by some of the participants, the “common” American soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Coast Guardsmen who took part in history’s largest combined air and sea military operation.

Authors Michael Green and James Brown have gathered a representative selection of accounts by men with their own individual views of the action. For example, Leonard Lebenson, one of the American soldiers who would be towed into France in a flimsy Waco glider, recalled the tension in the hours before the invasion was launched: “I was extremely nervous. I had to stop three or four times to urinate while we were on the airfield before loading onto the glider. I wasn’t the only one, of course, but we were all jumpy and nervous. We smoked a lot. We didn’t say too much. Finally, we got loaded. I didn’t know the people I was going with. As it turned out, it was very fortunate because there were many, many accidents in gliders, mainly from crashing into hedgerows, trees, or buildings.”

Another soldier, Sergeant Alan Anderson, a member of an antiaircraft unit that landed several hours after the initial waves hit Omaha Beach, discovered that the supposedly secured beach was still “hot” and deadly: “I heard a shell burst not more than five or six feet from me. It hit the bank where we had dug into the sand. I heard some fellow ask about his buddy, and one of our fellows, Luther Winkler, said, ‘He’s dead. His whole head is blown away.’ I went over to see how Winkler was, and his face looked like raw hamburger. He had been cut and the skin of his face was shredded. I don’t know how he ever survived that shell burst. We then had to get him out of there. I found a medic to help me….”

It is searing stories like these that stick in the mind and remind readers of the human cost of taking back a continent from a brutal enemy. A “must-read.”

Hell’s Gate: The Battle of the Cherkassy Pocket, January-February 1944, by Douglas E. Nash, HarperCollins, New York, 2009, 390 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $69.95.

Hell’s Gate: The Battle of the Cherkassy Pocket, January-February 1944, by Douglas E. Nash, HarperCollins, New York, 2009, 390 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $69.95.

Largely unknown in the West, 1944’s Battle of Cherkassy (also known as the Korsun Pocket) still stirs controversy in both the former Soviet Union and in Germany.

It was at Cherkassy where the last ounce of German offensive strength in the Ukraine was drained away, creating the conditions for the Soviet Army’s victorious advance into Poland, Romania, and the Balkans during the summer and autumn of 1944.

Eclipsed by a war of such gigantic proportions that saw battles of over a million or more men as commonplace, the events that occurred along the frozen banks of the Gniloy Tickich River should have faded into obscurity. However, to the 60,000 German soldiers who were encircled there at the end of January 1944, this was one of the most brutal, physically exhausting, and morally demanding battles they had ever experienced. Fully one third of them would not escape.

The culmination of years of research and survivor interviews, Hell’s Gate is a detailed, riveting, hour by hour, day by day account of the Wehrmacht’s desperate struggle analyzed on a tactical level through maps and military transcripts, as well as on a personal level, through the words of the enlisted men and officers who risked the roaring, ice-choked waters of the Gniloy Tickich to break out of the encirclement and avoid certain death at the hands of their Soviet foe.

For Country and Corps: The Life of General Oliver P. Smith, by Gail P. Shisler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2009, 324 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

For Country and Corps: The Life of General Oliver P. Smith, by Gail P. Shisler, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, 2009, 324 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $39.95.

Oliver P. Smith was a Marine officer who fought in the meatgrinder battles of Peleliu and Okinawa, then went on to command the 1st Marine Division in Korea during the amphibious invasion at Inchon, the recapture of Seoul, and the breakout from the “Frozen Chosin” Reservoir.

One of the 20th century’s great Marine combat leaders, O.P. Smith was widely regarded as an outstanding commander and a man of great intellect and moral (as well as physical) courage.

This biography, written by the granddaughter he helped raise (her father was killed during the war), illuminates the general’s remarkable life. Drawing on interviews, oral histories, official records, and private letters held by the family and not previously available to researchers, Gail Shisler paints a complete portrait of this larger-than-life but very human individual.

Her investigation of Smith’s relationship with his Army superiors in Korea, and with his Marine Corps peers and superiors takes exception to previously published descriptions and adds new insights into the Corps’ postwar battle for survival among the U.S. armed services. A terrific read about a towering, legendary warrior.

Special Ops, 1939-1945: A Manual of Covert Warfare and Training, edited by Stephen Bull, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 160 pp., photographs, illustrations, index, hardcover, $17.00.

Special Ops, 1939-1945: A Manual of Covert Warfare and Training, edited by Stephen Bull, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, 2009, 160 pp., photographs, illustrations, index, hardcover, $17.00.

How does one construct an exploding rat? Hide a secret message inside an innocent-looking tube of toothpaste? Create an incendiary suitcase? Sabotage a major military operation with the simplest of household products?

All these questions and many more are answered in this small, fascinating volume of secret tricks and techniques once employed by Allied partisans, spies, and saboteurs for whom all of German-occupied Europe was a battleground and where the normal rules of warfare were forgotten. For these undercover warriors, concealment of oneself, one’s weapons, and one’s equipment was vital, and so were the new methods and hardware that were constantly evolving in a life-or-death bid to stay ahead of the Gestapo and the enemy’s security services.

Silent killing, disguise, covert communications, and the arts of guerrilla warfare were all advanced as the war progressed. Clandestine war in the shadows, a deadly cat-and-mouse game, became a permanent part of the modern military and political scene.

Gleaned from dozens of manuals, and using the same photos and illustrations that once guided American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) and British Special Operations Executive (SOE) agents, Special Ops, 1939-1945 is chock full of surprisingly simple yet effective tools for waging a new kind of warfare that had no defined front line.

Stephen Bull’s compilation of scores of these once secret techniques creates a complete and authentic picture of the Allied spy. This is an essential pocket manual for anyone interested in unconventional warfare.

Hitler’s Chariots: Volume I—Mercedes-Benz G-4 Cross-Country Touring Car, by Blaine Taylor, Schiffer Military History, Atglen, PA, 2009, 176 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $49.99.

Hitler’s Chariots: Volume I—Mercedes-Benz G-4 Cross-Country Touring Car, by Blaine Taylor, Schiffer Military History, Atglen, PA, 2009, 176 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $49.99.

Anyone fascinated by the big, beautiful automobiles of the 1930s is sure to become entranced by this incredible volume of photographs, many previously unpublished, of the rugged, legendary Mercedes-Benz G-4 cross-country touring car.

Taylor, the author of the 1999 book, Mercedes-Benz: Parade and Staff Cars of the Third Reich, has outdone himself with this volume. Not only does he detail the history of the G-4, but also provides an interesting history of the prewar and wartime German automobile and panzer industries.

The huge, six-wheel Mercedes-Benz G-4, designed by Dr. Ferdinand Porsche and manufactured from 1934 to 1939, was a magnificent, iconic vehicle often seen in the books, films, and documentaries about the Third Reich. Only 57 of these beasts were manufactured, and only handful of them still survive today in museums and private collections, and Taylor recounts the history of many of them. Hitler owned several, as did Luftwaffe head Hermann Göring, in addition to other Nazi bigwigs.

Taylor’s lavishly illustrated book, with numerous shots showing Hitler and his G-4s in parades and at the front, will intrigue the history and automobile buff alike.

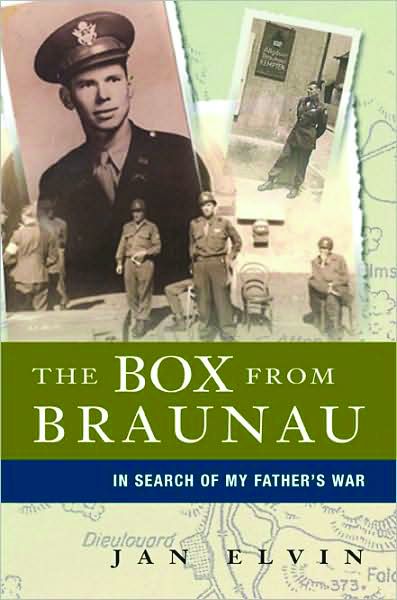

The Box from Braunau: In Search of My Father’s War, by Jan Elvin, Amacom, New York, 2009, 273 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.99.

The Box from Braunau: In Search of My Father’s War, by Jan Elvin, Amacom, New York, 2009, 273 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, hardcover, $24.99.

As a child in the years following World War II, Jan Elvin could not understand her father’s mood swings, his anxiety, his overly controlling behavior, his silence whenever the conversation turned to the war, or why she was advised by her mother never to stand close to him when waking her father from a nap.

It was only years later, shortly before his death, that she discovered that the keys to his emotional distance or unexplained explosive anger lay in a small tin box found in the attic, a box marked “Braunau 1944.”

She learned that her father, Bill, had been a war hero in General George S. Patton, Jr.’s Third Army and the 80th Infantry Division, that he had been awarded the Silver Star for gallantry in action, and had witnessed firsthand the bloodiness of the battlefield and horrors of the Nazi concentration camps when his outfit liberated the slave-labor camp at Ebensee, Austria. All these experiences, she then understood, had taken a terrible emotional toll on him, one that now has a name: Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD.

The Box from Braunau is both an emotional memoir of the unraveling and healing of a father-daughter relationship damaged by the ghosts of war and a sensitive chronicle of a veteran whose return to civilian life was marred by nightmares of combat and concentration camps.

Anyone who has had a relative come back from war with a changed personality and a refusal to talk about his or her experiences will find this book of immense help and insight.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments