By Peter Suciu

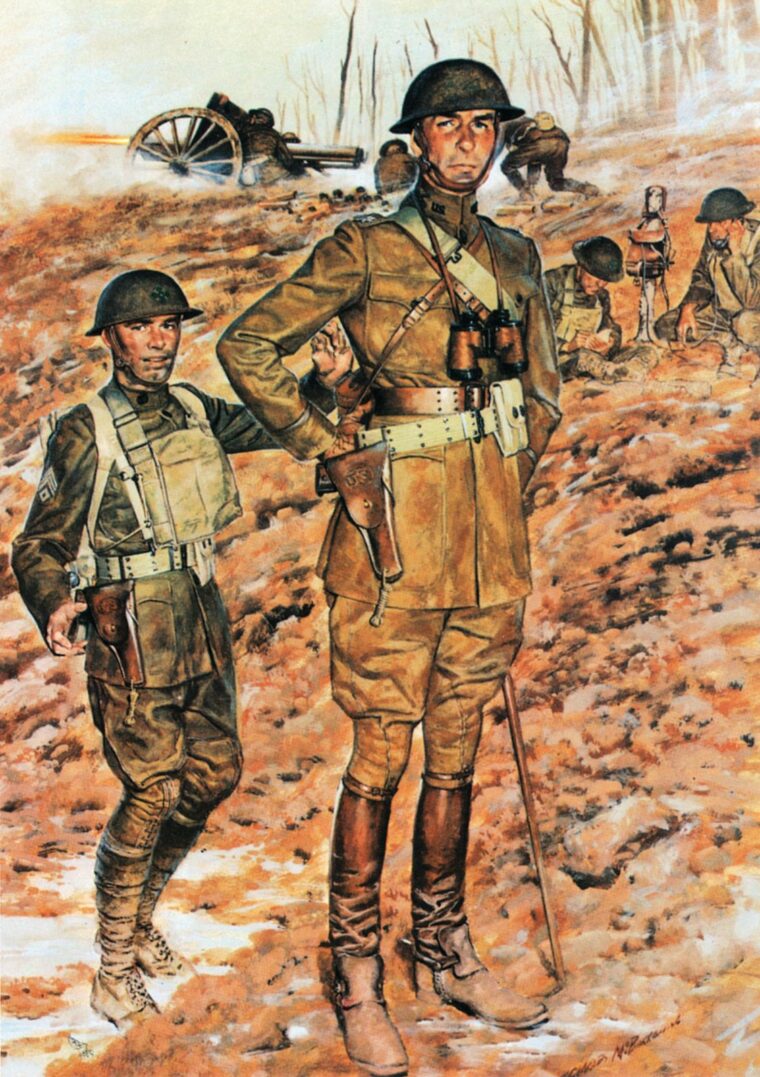

The American combat soldier today looks quite a bit different from his ancestor of 100 years ago. Besides the style of uniform, which now features a digital camouflage pattern to blend into desert surroundings, the fabrics today are far more breathable than the heavy wool that was worn when American soldiers went “Over There” in World War I. Helmets, boots, and small arms have also evolved. But one piece of gear has remained unchanged into the modern day—the combat equipment, or web, gear. Modern combat equipment is still very much a direct descendant of the M1910 pattern that was worn into the trenches and beyond.

Most nations in the 19th century issued leather belts, leather cartridge pouches, and leather packs to their soldiers. This was expensive to produce and, worse yet for the soldier, heavy and stiff. The leather had to be polished regularly because it was prone to drying out and cracking. It also tended to cause brass cartridges to corrode after prolonged contact, which was good for neither the ammunition nor the cartridge pouches. As the Germans discovered during the Allied blockade of World War I, such equipment required a steady supply of raw leather to produce. Given the demand for leather boots, belts, and gear, the Germans resorted to creating ersatz materials, notably when it came to the leather pickelhaubes, or spiked helmets.

While the Germans were facing leather shortages, the U.S. Army was already outfitted with canvas web gear. Partly because of the harsh terrain of the American West and partly as a money-saving effort, the Army had looked for a replacement for leather pouches. The first result was the adoption of the Mills cartridge belt in 1880, which was made of dark-blue machine-woven web. This was followed by the addition of the M1885 equipment, which included a khaki canvas haversack and a round, stamped-metal, cloth-covered canteen. This was the beginning of the American combat equipment that we know today.

The Mills belt remained in service during the Spanish-American War, and it was in the tropical climates of Cuba and the Philippines that the need heightened for a new combat gear system. Instead of a whole new system being devised and introduced, what followed was a series of slow improvements, most of them piecemeal. “The 1903 system is really the birth of the modern combat system,” says Scott Kraska of Bay State Militaria. “This follows with the M1910, when it was expanded and becomes a full set as opposed to pieces of equipment.”

The big change came not only because of a call for new material but also because the United States military had adopted a new rifle, the Model 1903 Springfield, which was fed with stripper clips of five rounds, where previous rifles were loaded a single bullet at a time. The need for a new belt was partly because of a new rifle. “In essence the United States Army needed equipment that was more practical,” adds Kraska. “The earlier belts had no flaps and the ammunition could fall out, and since the bullets were individual loops in the heat or dryness, it could be hard to get the bullets in and they often stuck when you were trying to get them out.”

About that time, the Army conducted studies on the equipment load its soldiers carried. One important consideration was the energy required for soldiers to carry their loads and how many calories were burned on a daily basis as a result. By lessening the burden, the Army determined, it would increase the greater fighting potential of the average soldier. Efforts were made to make his load as light as possible.

The resultant 1910 Infantry System would come into use for the next 50 years. The new M1910 cartridge belt featured 10 pouches for the Springfield .30-caliber ammunition. A variation of the belt was produced with stacked two-cell pockets for pistol cartridges, while another version was produced for revolver cartridges. The belts were made almost entirely of khaki webbing, with the few leather items produced in russet brown. The early M1910 pattern features snap fasteners bearing in relief the U.S. coat of arms, as did uniform buttons. All items were designated M1910.

The first major addition to the M1910 system was new equipment for mounted troops. Introduced in 1913 as the M1912, the equipment featured items carried specifically on the saddle. The infantry’s equipment was introduced a year later as the M1914; together these were known as the M1912/14 Cavalry Equipment. The biggest notable difference between the infantry version and the cavalry model was that the infantry’s cartridge belt was split at the back with a gap between the cartridge pouches. Five were worn on each side around the hips. The cavalry model featured nine cartridge pouches running from the middle of the back to the front, along with an additional two pistol-specific pouches on the left side. Additionally, the standard-issue leather pistol holster remained in use throughout both world wars.

To collectors today the webbing system is universally known as the M1910, but the true 1910 pattern is a little different from what followed. “To a casual observer and even to the Army at the time it was the same,” says Jeff Shrader of Advanced Guard Militaria. But collectors note the subtle differences with the M1910 and the World War I-era M1917/18 equipment. “This was a time of great change in color, construction details, and hardware fittings,” notes Shrader. “Basically, as we geared up for the AEF, contractors went to simplified and more robust fittings and heavier material in some cases.”

Shrader points out that the U.S. Army did not hesitate, however, to continue use of the older equipment, and this has led to some confusion today. “You see plenty of period photos of doughboys in France wearing the early ‘eagle snap’ gear,” Shrader says, noting the significant difference between the M1910 and the improved 1917 version. The 1910 version did feature the eagle snaps, but this was expensive to produce and resulted in the snaps corroding and tearing off. The new M1917/18 system utilized a “lift-the-dot” fastener, a large egg-shaped “doughnut” snap that fastened to a metal stud and was less prone to jamming by mud. It replaced the smaller snap fastener on most items manufactured after March 1917.

This has led to confusion about what truly constitutes the M1910 belt. “Generally, the M1910 belt is what it is called,” says Kraska, “at least by collectors. It was used throughout World War II. There are plenty of differences over the years.” Experts agree that this was the first truly practical equipment. “It used wire loops to affix things to, so the belts have plenty of holes to attach equipment,” notes Kraska, “and this meant soldiers could wear it in many configurations.”

While there was a recommended configuration, soldiers in practice had the ability to wear the equipment as they wanted. The M1910 and its variations proved to be the first great interchangeable system for carrying equipment. Kraska notes that some items still needed improvement. “The downside was that people couldn’t figure out the original pack, and soldiers hated it.” Eventually the pack was improved and the webbing evolved.

During World War I specialized belts were developed for the Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), with larger pouches for its cartridges, and for the web pistol belt, which would take the M1910 system in a whole new direction in the following war. “The pistol belt featured no pockets at all,” explains Kraska. “It was just a platform for other equipment. It was a narrow, three-inch belt, but it was meant to hang anything you wanted on it. There were pouches for ammunition, and all sorts of pieces were adopted for it, but it still comes out of the M1910 belt.” This belt featured a series of three holes evenly spaced out to allow for a variety of attachments at the bottom as well as suspenders from the top. It was adjustable in length from one end.

One of the more subtle changes to the various belts over the years was the buckle system. The original system had larger openings and featured curves with a “T” closure system. Gradually this changed to a tighter bend in the metal, and finally to more a reinforced metal buckle in 1936. Interestingly, the color of the belts also changed over time. The original belts were produced in a khaki color that faded to a light tan, but when American forces arrived in France in 1917 they wore green belts, although many earlier tan belts were issued as well. In the postwar years the belts went back to khaki and then back to green in 1943.

The belts continued to be worn through the Korean War, but following that conflict the Army adopted the M1956 Load Carrying Equipment (LCE) System, which saw the introduction of a new harness-suspender system that helped spread out the weight on the shoulders more than earlier suspenders. The ammunition pouches were also dropped, and the M1956 system was essentially based around the pistol belt, which allowed for a variety of items to be attached. The LCE was produced in olive green and was adjustable from both ends. It featured a rounded male-end buckle fastener. In 1961 experiments were conducted for a quick-release belt, called the Davis Belt. This featured a stamped-metal buckle with a bent tab that fitted through an opposing slot and remained closed through friction. The new belt was never widely adopted.

During the Vietnam War the equipment was upgraded again as the M1967 Modernized Load Carrying Equipment (MLCE) System. The MLCE improved the harness and featured improved pouches for ammunition and other equipment. It was another attempt to reduce the weight of the soldier’s load, and aluminum and plastic were introduced to replace the heavier metals of the LCE system. The new system was originally designed for use in tropical environments but eventually saw widespread use elsewhere as well.

Much was learned during the Vietnam War, and the MLCE was updated as the All-Purpose Lightweight Individual Carrying Equipment (ALICE) in the 1970s. Some of the improvements and changes remained in subsequent systems. The most notable change was the reduction of holes in the web belt, from rows of three to only a top and bottom hole, thus eliminating the seldom-used middle hole, and the addition of a plastic quick-release belt from the metal “T” loop buckle.

A special Individual Tactical Load Bearing Vest (ITLBV) was designed to replace the ALICE system, but its usage was limited to Special Forces and other select units. It was notable for featuring woodland-pattern camouflage made from Kevlar ballistic fabric and OG woodland-pattern nylon. The Army also adopted the Modular Lightweight Load-carrying Equipment (MOLLE) system, which features modularity through the use of PALS (Pouch Attachment Ladder System) webbing that allows for rows of heavy-duty nylon stitched onto the vest for attachment of accessories. It was first introduced in 1997 and has seen use by American troops in Afghanistan and Iraq.

As with anything, prices have continued going up. “Good quality World War II field equipment is all more expensive than it was a decade ago,” says Shrader. “Very rare stuff and items in particularly nice condition are still good sellers. What we used to call ‘meat and potatoes’ militaria—common field gear in average worn condition but still okay for display—has to be inexpensive to sell. In the absence of solid provenance linking an item to a specific important event or noteworthy individual, this type of stuff just won’t bring the same money it did a few years ago.”

Prices have risen for early M1910 equipment with the eagle snaps and “U.S.M.C.” stamped items. While the Marines followed the Army’s lead with equipment development, in World War II there was specific Marine-issued equipment. Those stamped with the “U.S.M.C.” are considered far rarer and thus more desirable than the Army versions.

Unfortunately, as with everything else, there are fakes and copies. The good news is that the fakes lack the quality of the real deal. “Mostly the quality is low and easy to spot,” says Shrader. He warns that some companies “have items that are just as good as the originals, and made in exactly the same way. Any serious collector is well-served to acquire some samples of the reproductions, or at the very least to familiarize themselves with some of the contract maker marks used at the front.” He adds that reproductions are a real double-edged sword. While these are certainly a minefield for future collectors, the availability of reproductions also means that fewer re-enactors are taking original material into the field to damage and destroy.

While not as desirable as a helmet or jacket, web gear is essential for anyone looking to do a complete uniform. The belts themselves are easily found, but collectors can add as much or as little detail as they desire, and the hobby can be quite specialized. The MOLLE system essentially ended the run of the old-style wear gear, but it is very much a direct descendant of equipment first issued more than 100 years ago. “We are really back to that turn-of-the century with mix and match scenario for the soldier’s individual field equipment,” says Shrader. “Today it seems like we are back to where we were in the period leading up to World War I, trying new things, lots of simple details on simple systems being revised and improved constantly.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments