By Al Hemingway

Many Americans view the conflict in the Pacific during World War II as primarily a series of land battles, mainly fought in a jungle environment between the American and Japanese armies. Although this is true, they may overlook the numerous naval engagements that had a significant impact on the Allied victory over the Japanese Empire.

In his new book, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941-1942 (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2011, 597 pp., photographs, maps, index, notes, $35.00, hardcover), historian Ian W. Toll digs deep into the personal lives of the leaders of decisive naval campaigns to give the reader a better understanding of their victories, as well as their failures.

Plebes, such as Chester Nimitz, Ernest King, and William “Bull” Halsey, Jr., entered Annapolis during the first half of the 20th century. Their tactical training was greatly influenced by naval historian Alfred Thayer Mahan, an 1861 graduate of the Naval Academy, whose book The Influence of Sea Power Upon History, 1660-1783, which he wrote in 1890, not only had a considerable impression upon U.S. naval strategy, but also influenced the other world powers including, ironically enough, the Empire of Japan.

On May 27, 1905, the Japanese soundly defeated Russia at the Battle of Tsushima. The Japanese victory sent shock waves around the world. With its victory, Japan emerged on the world scene as a force to be reckoned with—and much of it had to do with Mahan’s theories.

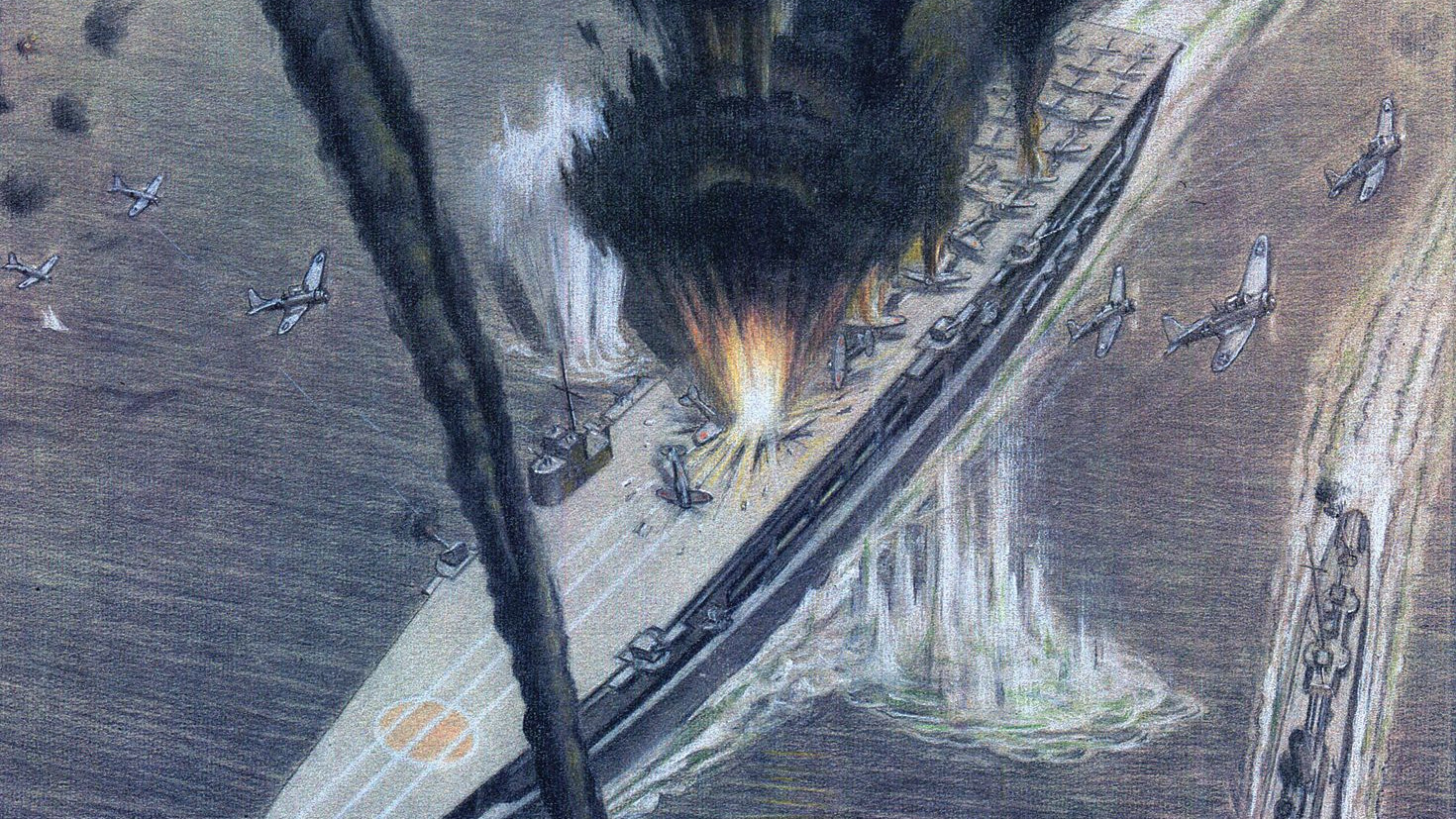

Japanese naval leaders continued to train and improve on their sea tactics during the decades prior to the outbreak of World War II. After their forays into Manchuria and China in the late 1930s, the Japanese suddenly struck at the U.S. naval base at Pearl Harbor in the Hawaiian Islands, plunging the United States into World War II.

The attack on Pearl Harbor was indeed innovative because it utilized massive air power at sea launched from the decks of aircraft carriers and did not employ the huge guns of battleships and cruisers.

Unfortunately, the Japanese strategy of the “decisive battle doctrine” did not serve them well. Although they destroyed or damaged numerous vessels at Pearl, they failed to eliminate the U.S. aircraft carriers that were out at sea. Some months later, at the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, neither side’s surface vessels came within sight of one another. The U.S. victory at Midway was a turning point in naval warfare—and ultimately led to the defeat of Japan in 1945.

Unfortunately, the Japanese strategy of the “decisive battle doctrine” did not serve them well. Although they destroyed or damaged numerous vessels at Pearl, they failed to eliminate the U.S. aircraft carriers that were out at sea. Some months later, at the Battles of the Coral Sea and Midway, neither side’s surface vessels came within sight of one another. The U.S. victory at Midway was a turning point in naval warfare—and ultimately led to the defeat of Japan in 1945.

Toll delves into the life of Nimitz’s counterpart in the Pacific, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto— a 1904 graduate of the Japanese Naval Academy—who was the chief architect of the Pearl Harbor attack. Wounded during the Battle of Tsushima, when 120 pieces of shrapnel pierced his body, causing him to lose the index and middle fingers of his left hand, Yamamoto traveled through the United States extensively in the 1920s, even learning English at Harvard University.

His firsthand knowledge was instrumental in his attitude toward the United States. He developed a “healthy respect” for the industrial might of the country, saying, “Anyone who has seen the auto factories in Detroit and the oil fields in Texas knows that Japan lacks the national power for a naval race with America.”

The author adeptly weaves the tactics learned decades earlier at their respective military institutions to illustrate how the American and Japanese leaders formulated their plans of action during the early stages of the conflict and implemented them on the high seas.

At least one former U.S. president foresaw the war with Japan when he penned a note to the newly appointed Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt in the spring of 1913. Theodore Roosevelt, FDR’s fifth cousin, congratulated him on his position and offered words of caution, stating, “I do not anticipate trouble with Japan, but it may come, and if it does it will come suddenly.”

Indeed, TR’s prediction came to fruition 28 years later on a sleepy, Sunday morning in Hawaii, and involved the United States in yet another global conflict that would cost the lives of millions of people throughout the world.

Free France’s Lion: The Life of Philippe Leclerc, DeGaulle’s Greatest General by William Mortimer Moore, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2011, 544 pp., maps, illustrations, index, bibliography, $32.95, hardcover.

Free France’s Lion: The Life of Philippe Leclerc, DeGaulle’s Greatest General by William Mortimer Moore, Casemate, Havertown, PA, 2011, 544 pp., maps, illustrations, index, bibliography, $32.95, hardcover.

Born into an aristocratic family in 1902, Philippe Francois Marie de Hauteclocque, or as he would come to be known, General Philippe Leclerc, was one of France’s top military commanders in World War II. With the possible exception of Charles de Gaulle, he was foremost in instilling pride and a strong sense of nationalism among the French people during World War II, helping to defeat the Nazis.

On October 1, 1924, the young Hauteclocque graduated from the French military academy at Saint-Cyr. From there he was transferred to the cavalry school at Saumur, where 11 months later he would leave at the top of his class and be assigned as a troop commander with the 5th Regiment des Cuirassiers based at Trier. He and his bride, Therese, settled down to garrison life. In 1929, he was sent to French Morocco to participate in the fighting to put down the insurrections by tribal leaders. But the fiery Frenchman’s real abilities as a military commander would shine as 1940 quickly approached.

When the German juggernaut overran France in 1940, Hauteclocque evaded the Nazis until he was finally captured, not just once, but twice. Quick on his feet, he managed to persuade them that he was just a private and was going home to his family. It was here that he first used his alias Leclerc, a name that would stick with him the remainder of his life.

The French leader Charles de Gaulle, who had established his headquarters in London, was impressed when he first met Leclerc and sent him to Africa. Although Leclerc did a magnificent job in fighting the Italians and the famed Afrika Korps, he was pushed aside for the mysterious Henri Giraud, who seemed to have an agenda of his own. Because of this, Leclerc resented Giraud.

Gaining notoriety during the African campaign, Leclerc soon commanded the 2nd French Armored Division attached to General George Patton’s Third Army and to the First Army during the Normandy breakout. When Paris was liberated in 1944, Leclerc’s unit rode triumphantly through the streets amid throngs of well-wishers. He continued to demonstrate his dynamic leadership capabilities as the Allies pushed their way into Germany itself until the Nazis surrendered in May 1945.

After the war, Leclerc was assigned to Indochina where the growing insurgency under a little-known leader named Ho Chi Minh was gaining grassroots support. He immediately grasped the situation and advised the French government to “negotiate at all costs” because he saw that France would be dragged into a protracted war.

If not for his untimely death in an airplane crash in 1947, Leclerc might have convinced everyone that he was correct in his assessment. We will never know. But one thing is certain, if Philippe Leclerc had not died, the situation in Southeast Asia may have turned out completely differently, for France as well as America.

Fighting for MacArthur: The Navy and Marine Corps’ Desperate Defense of the Philippines by John Gordon, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 384 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

Fighting for MacArthur: The Navy and Marine Corps’ Desperate Defense of the Philippines by John Gordon, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2011, 384 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

The 4th Marines have the dubious distinction of being the only U.S. Marine regiment to surrender as a unit to the Japanese during the fighting for Corregidor, commonly referred to as “the Rock,” in the Philippine Islands in May 1942.

Numbering fewer than 1,600 men, the Marines formed a 4th Provisional Battalion comprised of sailors that knew precious little of infantry tactics. Despite this, they put up a stiff resistance when the Japanese landed on May 5, 1942, and performed remarkably well.

The author, a former U.S. Army officer and senior defense analyst, uses never-before-seen documents to give a detailed account of the battle and its aftermath.

He also provides interesting analysis of the steps the Army, Navy, and the Marines could have to taken to improve their harrowing situation. First, Gordon states that U.S. submarines could have done a better job by attacking the enemy transports delivering troops and supplies to the “Rock.” The Army could have given Admiral Thomas C. Hart some advanced warning so he could have delivered additional fuel to Bataan and Corregidor. Also, the Leathernecks might have conducted raids to eliminate some of the Japanese heavy artillery that came back to haunt the defenders.

Colonel Samuel Howard, commanding officer of the 4th Marines, should have strengthened his reserves and created a more formidable defense along the island’s north shore. Lastly, the troops went into battle lacking heavy weapons and without tank support that could have greatly improved their situation.

In spite of all of these factors, Gordon stresses that the Japanese still would have seized Corregidor and Bataan. But the sacrifice of those who were killed, wounded, and spent years in horrid Japanese death camps was not in vain. Their stand against a numerically superior enemy force was nothing short of inspirational and rallied the American people in the dark, early days of World War II.

Surrender Invites Death: Fighting the Waffen SS in Normandy by John A. English, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2011, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Surrender Invites Death: Fighting the Waffen SS in Normandy by John A. English, Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, PA, 2011, 240 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Feared by many and fearless in battle, the elite soldiers of the Waffen SS were courageous on the battlefield but utterly ruthless with their opponents, especially if they were captured as prisoners of war.

Originally formed as Hitler’s bodyguard in 1925, the Schutzstaffel, or protection squad, mushroomed into panzer and infantry units as the war progressed. Their ferocity and tenacity in battle were extraordinary. Just the word that SS units were being engaged caused concern among the Allied troops.

In 1942, SS units were equipped with the latest weapons in the German arsenal. Augmented by two panzergrenadier regiments, Waffen SS divisions were larger than the armored divisions of the regular German Army.

When the Allies came ashore in Normandy in June 1944, Waffen SS units were rushed to the battlefield to halt their advance. The 75mm guns of American Sherman tanks were no match for either the German Panther or Tiger tanks, mounting 75mm and 88mm high-velocity cannon, respectively. The British, however, had the Firefly, a modified Sherman that possessed a turret-mounted 17-pounder antitank gun that could pierce the armor of both vehicles.

The fighting that raged between Allied and SS units was down and dirty. Nazi propaganda said Americans scalped prisoners. Soldiers from the 115th Regiment, 29th Infantry Division took no prisoners when they heard German troops were bayoneting captured Allied soldiers, and one Canadian trooper wrote in his diary of “settling scores with the 12th SS.”

As the author states, the record of Waffen SS atrocities “remains a dark stain on the otherwise commendable fighting record of a unique force that vainly tried to save what God had abandoned.”

And in the end, despite the fierce reputation of the SS in combat, Allied troops forced them to withdraw as they took the war to the German homeland.

Short Bursts

The German Aces Speak: World War II Through the Eyes of Four of the Luftwaffe’s Most Important Commanders by Colin D. Heaton and Anne-Marie Lewis, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 354 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.00, hardcover.

The German Aces Speak: World War II Through the Eyes of Four of the Luftwaffe’s Most Important Commanders by Colin D. Heaton and Anne-Marie Lewis, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 354 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.00, hardcover.

This is not another book about pilots who flew in World War II, but rather a personal look at the German adversaries that Allied pilots faced in the skies over Europe, Africa, and the Mediterranean.

The authors have selected four top German aces—Walter Krupinski, Adolf Galland, Eduard Neumann, and Wolfgang Falck—who have an incredible list of aerial victories to their credit and a host of personal awards.

These soldiers of the skies fought heroically for their country despite their aversion to the Nazi Party and its leaders. Krupinski, who had 197 victories and died in 2000, said, “We will be forever tied to the monsters that ran our country into the ground, killed millions, and ruined the great culture and prestige of Germany. It will take many years to remove the stain. I am also asked for advice, and I have some. Don’t trust dictators or madmen.”

Battery! C. Lenton Sartain and the Airborne G.I.s of the 319th Glider Field Artillery by Joseph S. Covais, Andy Red Enterprises, 2011, Winooski, VT, 576 pp., $19.99, photographs, bibliography, softcover.

Battery! C. Lenton Sartain and the Airborne G.I.s of the 319th Glider Field Artillery by Joseph S. Covais, Andy Red Enterprises, 2011, Winooski, VT, 576 pp., $19.99, photographs, bibliography, softcover.

As a child, Joseph Covais would sit watching the television series Combat with his father, Salvatore Covais. The elder Covais, a veteran of Battery A, 319th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, 82nd Airborne Division in World War II, would remark to his son that some of the scenes were pure Hollywood.

The younger Covais would listen intently when his father talked about his exploits, and he vowed to someday write an account of the officers and men who participated in the various campaigns of the conflict.

Salvatore Covais passed away in 2004, and his funeral was held on June 6, exactly 60 years to the day after the Normandy invasion. His medals and decorations were proudly displayed near his casket. This served as the impetus for the author to begin researching a book about his father’s unit. Sal Covais, as his son writes, was an emotional person when he described his wartime experiences, especially when he discussed those who did not return from the war.

“I am an airborne trooper, and I love this country,” his father said. “If the country called me again I would go back again, I would do that, I would do that.”

The Final Mission of Bottoms Up: A World War II Pilot’s Story by Dennis R. Okerstrom, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2011, 254 pp., $29.95, photographs, notes, index, hardcover.

The Final Mission of Bottoms Up: A World War II Pilot’s Story by Dennis R. Okerstrom, University of Missouri Press, Columbia, 2011, 254 pp., $29.95, photographs, notes, index, hardcover.

This is a riveting story of a survivor of a downed Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber who was captured after the aircraft crashed, survived months as a prisoner of war, and return to the crash site years later to discover what happened to his fellow crew members.

A Missouri native, Lieutenant Lee Lamar was the plane’s co-pilot on its 21st and last mission. After the Liberator, nicknamed Bottoms Up, was rocked by a German antiaircraft shell over southern Italy, both Lamar and pilot 1st Lt. Randall Darden struggled desperately to keep the plane airborne. However, when a second round struck her over Croatia all eight crew members realized that they would have to bail out.

Captured, Lamar was released and returned to the United States in June 1945. It would be decades later when a Croatian archaeological team unearthed pieces of Lamar’s Liberator. The author describes the emotional experience as Lamar and his family returned to Croatia in 2007 and examined fragments of Bottoms Up. Lamar also talked to the Croatian partisans who assisted in rescuing members of the plane’s crew.

Lee Lamar had come full circle, returning to the spot that had altered his life forever and getting answers to questions that had haunted him for more than 60 years.

Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini’s Wars, 1935-1943 by Patrick Cloutier, 2011, 225 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, $27.95, softcover.

Regio Esercito: The Italian Royal Army in Mussolini’s Wars, 1935-1943 by Patrick Cloutier, 2011, 225 pp., maps, illustrations, photographs, $27.95, softcover.

A rare book that is worth the effort to locate if the reader is interested in the battles and campaigns of the Italian troops in Ethopia, Spain, and World War II. This is a detailed account that includes maps and rare photographs of many of the successes the Italian Army had but have received scant attention from historians.

By the time the Americans entered the war in 1942, Italy, which had been fighting for nearly eight years, was tired. After the country’s surrender in 1943, the German occupying force demonstrated little sympathy for the civilian population.

This is a must read to gain a better understanding of the Italian Army’s pivotal role in World War II.

Douglas DC-3 Dakota 1935 Onwards (All Marks): Owners’ Workshop Manual by Paul and Louise Blackah, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 160 pp., illustrations, photographs, index, $28.00, hardcover.

Douglas DC-3 Dakota 1935 Onwards (All Marks): Owners’ Workshop Manual by Paul and Louise Blackah, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2011, 160 pp., illustrations, photographs, index, $28.00, hardcover.

The Douglas DC-3 Dakota, or its military designation the C-47, was a veritable workhorse in every theater of operation during World War II. It transported troops and supplies, dropped paratroopers in Operations Overlord and Market-Garden and, as one pilot later said, “She was almost flawless and a real lady.”

Described by the authors as an engineer’s dream it is no stretch to say that the plane played an important role in the Allied victory. This book goes into great detail about the engine parts, control system, propellers—literally every nut and bolt of the aircraft—and how to properly service the plane.

As a testament to the DC-3, General Dwight David Eisenhower reportedly said that there were four items that won the conflict: the bazooka, the jeep, the atomic bomb, and the C-47 “Gooney Bird,” the nickname given the C-47 by American troops. Ike was probably right.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments