By Jason Antonio

Norvald Flaaten never expected he would appear in a movie when he signed up with the Canadian Army during World War II, but the subject of the movie and what he had to do was too good to pass up.

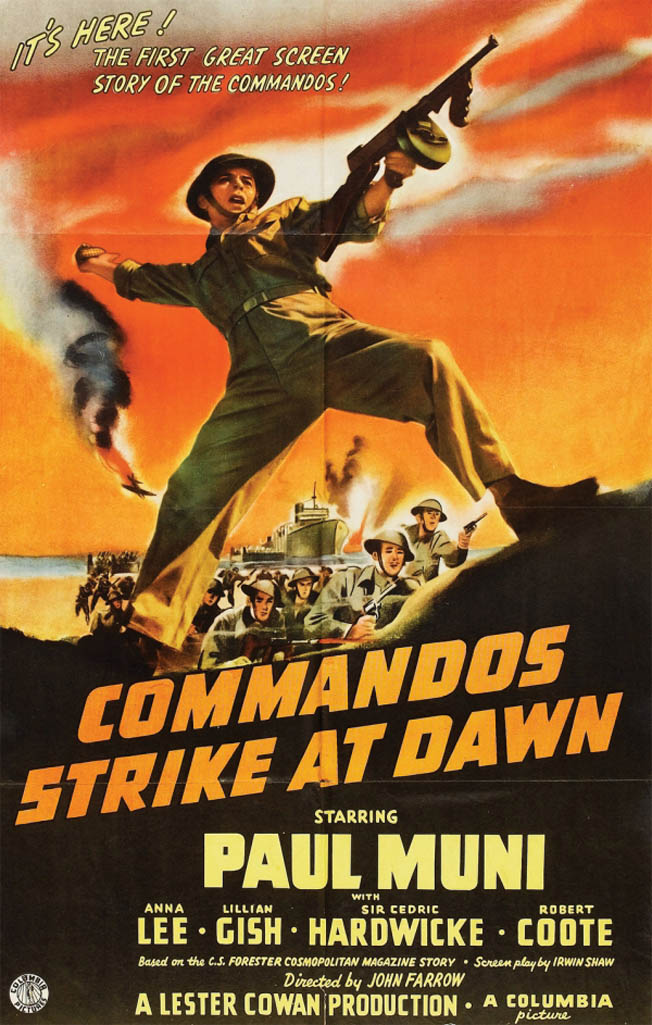

The film was called Commandos Strike at Dawn and was being produced on the Heals Rifle Range in Saanich, British Columbia. The story was about a gentle widower (not Norvald), who, after seeing atrocities committed by the Nazis in his peaceful Norwegian fishing village, escapes to Britain and returns later leading a commando force against the oppressors.

The commando force would include soldiers from Britain, with real Canadian soldiers acting as extras, leading the charge in routing the Nazi occupiers and recapturing the small Norwegian village.

The director had a special job for Norvald in the movie. The Canadian would appear as one of the hundreds of extra commandos taking part in the assault. However, he would also appear at the end of the movie for a few seconds and complete an important task. The director instructed Norvald in how he wanted the scene to play out.

“He said, ‘At the end of this movie, I want you to pull down the swastika [flag]. Pull it down roughly, ruffle it up and throw it on the ground. Then pick up the Norwegian flag, unfold it very carefully, tie it on to the rope of the flagpole and hoist it up slowly. While you’re doing this, I will have the camera on you taking your picture.’”

So Norvald did as he was instructed and rehearsed the shot a few times to get it as perfect as possible. After completing his assignment, it was back to Camp Colwood for more training.

Commandos Strike at Dawn was released to the public on January 27, 1943, across Canada and the United States and in England later that year. By then, Norvald’s training had shifted 860 miles east to Regina, Saskatchewan, where he had enlisted in 1941. Walking through downtown Regina while on a leave, Norvald came across the movie in a theater and stepped in to watch the film and witness his few seconds of fame.

“I was given a key role in this movie, and I felt quite honored by that,” the Canadian veteran said proudly, adding that taking part in the movie was one of the highlights of his Army training. “I don’t know why I got the role, but maybe it’s because I am of Norwegian descent and the sergeant major knew this. He, too, was of Norwegian descent.”

A Chance to Get Off the Farm

Norvald Scotty Lystrup Flaaten was born on March 25, 1920, in Glenwood, Minnesota, the second of six children born to Nels and Annie Flaaten. Nels was originally from Norway and in 1902 moved to the United States, where he met Annie and worked on her father’s farm for a short time. The two were married in 1917 and later moved to Canada, as Nels had purchased a piece of land years earlier, cultivated it, and started a homestead. The homestead and farm were located in southeast Saskatchewan, near the small hamlet of Grassdale, about 62 miles southeast of Regina.

During a trip to see family in Glenwood, Norvald was born. Once the family was back home on the farm, Norvald went to a one-room country school until the ninth grade. By that point, since he was the oldest boy in the family, he was needed on the farm to milk cows and look after the general day-to-day affairs of a farming family. Norvald and his family were able to just get by during the long decade of the “Dirty ‘30s,” or the “Hungry ‘30s” as the Flaatens came to know it. During this period Norvald realized farming was not for him.

After war broke out in 1939, he waited another two years before deciding it was time to get off the farm. On August 27, 1941, at the age of 21, Norvald was driven to the train station near Grassdale by his father and brother. He jumped on a train that ended up taking him to the initial training center in Regina.

“We did all kinds of medical tests, blood tests and x-rays. And the doctors—they were called medical officers—determined if we were fit for Army training. I was stationed in Regina for two months and took my basic training there from September through October 1941. Then I moved on to Currie Barracks in Calgary.”

“Advanced training included quite a bit, [such as] classroom instruction,” Flaaten remembered. “The subject I loved most was map reading. I loved Calgary. We could see out to the foothills and the Rockies, and I spent my first Christmas away from home in Calgary. Then in January of the next year [1942] we moved on to Burrard Barracks in Vancouver, [British Columbia].

“Six Months in Desolation” on Kiska

From Vancouver the soldiers moved on to Vancouver Island and Colwood Camp, just west of Victoria. It was during this time that Norvald made his brief big screen appearance. A year later the soldiers finally deployed to an area of possible contact with the enemy. The scene was Kiska, a small island in the Aleutian chain off the coast of Alaska. The Japanese had invaded Kiska on June 6, 1942, and the neighboring island of Attu the next day.

For this excursion, Norvald was attached to the Rocky Mountain Rangers battalion, part of the 13th Canadian Infantry Brigade, 6th Canadian Infantry Division. This group was made up of roughly 4,800 to 5,300 Canadian soldiers. The battalion left Vancouver Island on July 12, 1943, and landed on Kiska on August 15.

“Lo and behold, somebody had warned the Japanese we were coming and they made their escape before we arrived,” Norvald recalled. “They lived underground in most places on Kiska. And we went underground where they had lived and found some kettles of rice on the stoves, which they had been boiling. And this rice was still lukewarm. So you can tell how close we were to meeting up with the Japanese.”

“It was quite depressing up there because there was no civilization,” said Norvald. “All we saw was blue fox and some hawks, crows and eagles flying by. So we spent six months in desolation. We were happy when the Americans brought some movies up. We could actually see people moving and playing in the movies. And that was very, very cheerful.”

The Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada

After their six-month stay on Kiska battling strong winds and inclement weather, in January 1944 the Canadians sailed back to Victoria, where they then proceeded to Vernon, B.C. Here they were subjected to a “very strenuous” commando training course. This included going through caves, trenches, and underground tunnels filled with tear gas. They also walked on a cable 50 feet above a wide body of water while clinging onto a rope overhead.

“What a relief to reach the other side of the water,” Norvald added with a chuckle.

Flaaten was also privileged to take a driver mechanic course, which included half- and three-quarter-ton trucks, Bren gun carriers, tanks, and other types of vehicles. Since he received the title of driver mechanic, he was eligible for trades pay and was considered a tradesman, the equivalent of a corporal in the army. He held this title until the end of the war.

From Vernon, Norvald and the rest of his unit traveled east to Ontario and then on to Halifax, Nova Scotia, on the Atlantic coast. The troopship Queen Mary then crossed the Atlantic Ocean and landed in Rayburn, England, on May 25, 1944. There the troops received more field training and joined newly assigned battalions.

Norvald joined the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada, which was part of the 6th Brigade, 2nd Canadian Division. The two sister regiments of the brigade included Les Fusiliers Mont-Royal and the South Saskatch-ewan Regiment. Nearly two weeks later, the D-Day landings took place in Normandy.

Landing in France After D-Day

The Queen’s Own did not take part in the initial D-Day landings, but instead landed a month later on July 7, 1944, at Graye-sur-Mer, France. From then until the end of the war, the Highlanders faced the difficult task of attacking and destroying German strongholds along the coast of France and up into Belgium, Holland, and finally into Germany.

Upon landing, Norvald was immediately placed in the front lines as a Bren gun carrier driver. “We hit Normandy. It was dark in the evening and rained all night…. We couldn’t put the lights on the carriers because the enemy might spot us and bomb us. The way we traveled was by using the differential on the tails of the vehicles, which were painted in bright white. The motorcycle went ahead with an officer and we followed behind.

“I kept my eyes on the white differential ahead of me and that’s how I stayed on the road,” Norvald continued. “When the morning came, we were so happy to see some French women out on the road to meet us, as they had a hot pot of coffee. That sure was a Godsave.”

Besides driving a Bren gun carrier, Norvald was also assigned to the three-inch mortar platoon as part of the support headquarters company. Each carrier had a crew of four to five men along with the mortar, which fired 10-pound bombs. When they had to stop and fight, one soldier would pick up the 50-pound base plate and set it on the ground, a second would insert the barrel into the plate, and a third would set up the tripod just under the barrel.

“We would fire when the platoon commander said fire. We kept dropping the bombs into the barrel, and it would fire for three-quarters of a mile, over a hill, on trenches, at installations, or wherever the enemy was embedded,” Norvald explained. “I remember the times when we fired so hard and fast that the barrels of our mortars got red hot. In that instance the platoon commander had to say stop fire, because the enemy were flying overhead and they would spot these red barrels and drop bombs on us. We were bombed, but fortunately I didn’t get hit.”

Norvald Under Fire

There were a couple of close encounters with enemy fire. Once Norvald and eight men from his company were standing in a stairwell leading to the basement of a house, and because they were all quite tired, had taken refuge there for a while. Norvald thought, “Well, what’s the use of standing here when there is a newly dug trench a few feet away?” so he took some blankets and went to sleep in the trench.

When he awoke the next morning, he discovered an antitank shell had made a hole in the side of his Bren gun carrier, while his Bren gun, which had been close by, had been hit by an artillery shell and smashed to pieces. His comrades were still in the stairwell and pointed out that he had been below ground when the shelling had started. “They were OK, they were safe. They had enough sense to stay there until the shelling and bombing was over.”

On another occasion, Norvald’s company had taken refuge in a vacant farm house, where they came upon some porridge which they decided to eat for breakfast. Unfortunately, they had no milk to put on it, but they spotted a herd of dairy cattle grazing in a field nearby. Since Norvald was familiar with milking cows, he volunteered to go out with a four-liter pail to get some milk.

“I had milked half the pail when a colt came over and scared the cow away, and that was the end of my milking,” he continued. “I had enough milk, so I picked up the pail and started toward the house. I had walked about 500 yards back to the house when a large shell landed and exploded right where I had been sitting. They were aiming at me because they had seen me and thought they could get rid of the cattle and soldiers. So I have loved horses ever since. That was a good colt.”

After finishing up in Normandy, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders, along with the rest of the Canadian Army fighting in France, turned northeast and headed into Belgium and later Holland. Hand-to-hand fighting took place for Norvald and others in Belgium, while they also continued to shell the Germans who were dug in in Holland.

“The Germans had invented a ‘moaning Minnie,’ and that shell was designed to demoralize the Allied troops,” Norvald recalled. “They went over our heads and to either side. Whooooooo. What a screech! Boy we really hated the sound of those moaning Minnies. [But] we finally managed to get through Holland.”

Casualties After Armistice

After spending Christmas 1944 in Amersfoort, Holland, the Canadians then cleared out the rest of Holland and moved into Germany itself. Norvald had a few more close calls while fighting through heavy forests, which the Germans continuously shelled as the Allies advanced. Norvald pointed out that it was so dark in some places that he could not even see a few feet ahead. The soldiers had to keep their hands up in front of them to avoid being hit in the face by low-hanging branches.

“It was very scary to be in the forest. We just marched ahead. There was no retreat, [just] keep going,” Norvald recalled. “Prayed to God to get us through there safe. We lived in trenches underground, me and some of my buddies. We ate underground and existed underground for a lot of the time that we were in the front lines.”

The Canadians later entered the city of Oldenburg, Germany, where on May 5, 1945, they received the news the war was over and that the armistice would be declared on May 8. The end of the war was a time of rejoicing. When the officers made the announcement, Norvald was one of the more fortunate ones to hear it right away. However, there were still some Canadian troops fighting who did not hear the announcement until four or five days later. A number were killed during that period.

“I can remember distinctly that there were four soldiers from my company riding in a quarter-ton truck, and these four soldiers were all killed and that was after the ceasefire,” Norvald recalled. “They died by a mine or roadside bomb, like what they use now in Afghanistan. They hit a roadside bomb and it exploded.”

Norvald After the War

After spending a few more months in Holland and Germany doing garrison duty, the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders began to sail back to Canada, arriving on November 22, 1945. After receiving leave to go home for Christmas, Norvald was finally discharged from the Army in Regina, where he had originally enlisted, on January 24, 1946.

For his efforts in the war, Norvald received the Volunteer Medal and Clasp, the Defence of Britain Star, the France and Germany Star, and the European King George VI medal.

Although he did not take part in the 1942 Dieppe raid, Norvald did have the opportunity to travel to that city in August 1992, with 40 other veterans for the 50th anniversary of the raid. While passing through the city of Kent, England, during the tour, many of the men had the opportunity to shake hands with the Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip. The Duke had arranged to be there at a specific time, so the people in charge told Norvald and the others they were to go into one particular building, where they would be meet the man.

“The Duke of Edinburgh made it a point to walk around the building and shake hands with each individual soldier,” recalled Norvald. “One question he asked each of us was what battalion or regiment we served with. He came to me and said, ‘What regiment were you in?’ I said, ‘I am in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders of Canada.’

“He said, ‘Oh my goodness, that’s my wife’s regiment.’ He shook my hand and squeezed a bit harder than I expected him to do. I didn’t know if he was going to let go. He added, ‘It was nice to meet you and that you serve in my wife’s battalion.’ So he went on to the other soldiers. When I told my family about this, they were both surprised and thrilled that I had met the Duke of Edinburgh.”

Norvald Flaaten lived in Weyburn, Saskatchewan, with Helen, his wife of 60 years. He passed away in October 2011 after complications from a fall. Even into his 90s, he spoke to students about his experiences and wrote articles for medical journals. He also contributed to The Memory Project, an initiative designed to capture Canadian veterans’ experiences through pictures, written word, and audio interviews. To listen to Norvald discuss his experiences, visit thememoryproject.com/ home.aspx and type “Norvald Flaaten” into the search bar.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments