By Al Hemingway

On the hot, humid afternoon of May 22, 1934, a one-seater Buhl “Pup” aircraft slowly descended from the skies over a large field near the all-black Tuskegee Institute in eastern Alabama. The aircraft landed smoothly, and out stepped the person flying the monoplane, John C. Robinson, himself a Tuskegee graduate 11 years earlier. The students were awestruck. None of them had ever seen a black pilot before; it was something they thought impossible in the strict “Jim Crow” segregated world of the South. But Robinson had a dream—and he was here to promote it. He wanted to start a training program for young African Americans, male or female, to become licensed pilots.

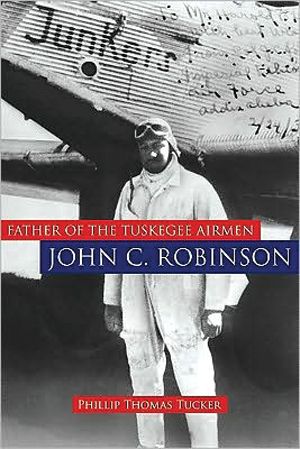

In his latest offering, Father of the Tuskegee Airmen: John C. Robinson (Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2012, 329 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover), historian Phillip Thomas Tucker has written a marvelous account of a man who has received little attention in history for his achievements in aviation, fighting racism, both in the United States and abroad, and his tireless efforts to have his alma mater create a program so African Americans could learn to fly.

In his latest offering, Father of the Tuskegee Airmen: John C. Robinson (Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2012, 329 pp., photographs, notes, index, $29.95, hardcover), historian Phillip Thomas Tucker has written a marvelous account of a man who has received little attention in history for his achievements in aviation, fighting racism, both in the United States and abroad, and his tireless efforts to have his alma mater create a program so African Americans could learn to fly.

Unfortunately, Robinson’s lofty ideas were a shock to white Americans, especially those in the South. Growing up in Gulfport, Mississippi, Robinson experienced firsthand racial inequality. But he did have parents who believed a good education was the key to escape the strict segregation in the South. They knew by moving north possibilities existed for young black Americans to succeed.

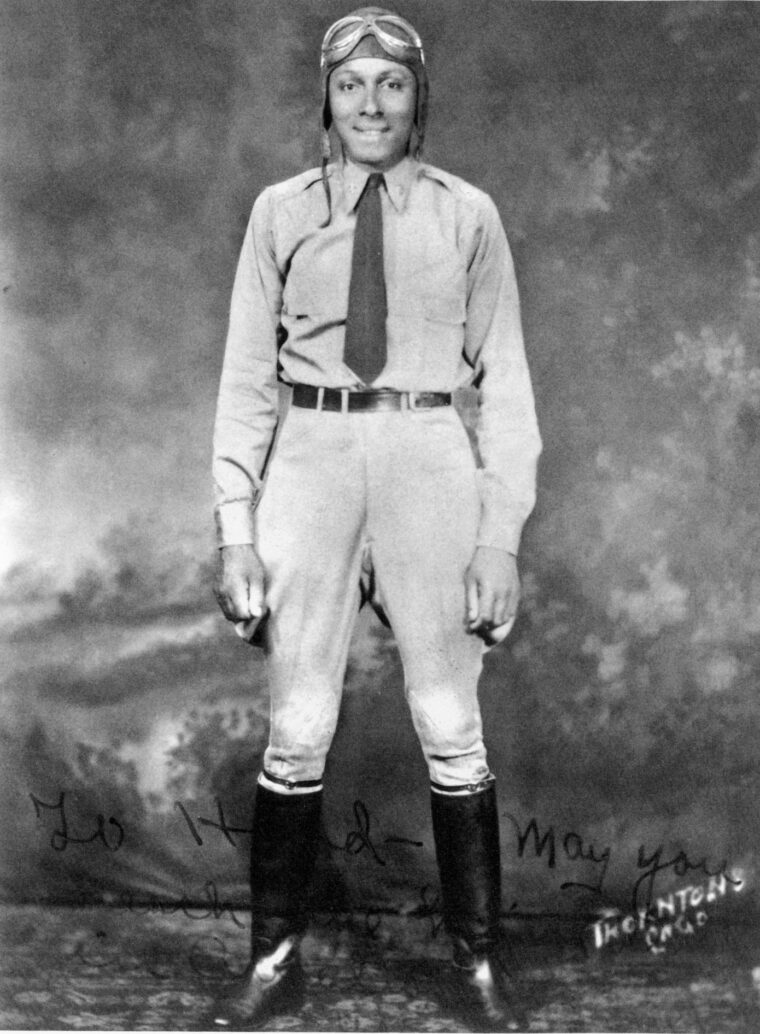

And Robinson did just that. After graduating from Tuskegee, he moved to Chicago and began working as an automobile mechanic. He was so skilled in his trade he soon opened his own automobile and motorcycle shop. A persuasive, intelligent individual with a magnetic personality, Robinson managed to convince the board of directors at the all-white Curtiss-Wright Aeronautical School to enroll him in classes. He took a job as a janitor and became the school’s first African American graduate and even taught classes to both black and white students.

Robinson’s greatest accolades and, ironically, disappointments, came when he traveled to Ethiopia, when Emperor Haile Selassie asked for black volunteers to create an all-black air force to help defeat the Italian Army that was poised to strike his country. Selassie would eventually appoint Robinson a colonel and make him the head of his air force. Although not much of an air force, Robinson worked tirelessly to recruit, train, and fly combat missions when war broke out in 1935.

For a year, Robinson fulfilled his duties. He was wounded and gassed on several occasions. More important, the conflict in Ethiopia changed his views dramatically. He came away from it, like many combat veterans, cynical and disillusioned. His Pan-Africanism, that is Africa for Africans, diminished as well. Although he loved the Ethiopian people, the institution of slavery still existed. He watched in horror the indiscriminate bombing and lethal gasses dropped not only on military targets, but also the civilian population. He was also bitter that none of the members of the all-black Challenger Aero Club traveled to Ethiopia to assist in the fight against fascism and the subjugation of the Ethiopian people.

Robinson returned to the United States a changed man. His metamorphosis was detected by his friends and family. Although he had difficulty breathing from the gas attacks, he crisscrossed the country making speeches and raising money for financial aid for Ethiopia, despite the fact that the country had collapsed when the Italians seized the capital city, Addis Ababa, in May 1936.

There remained one dream Robinson wanted to fulfill, the creation of an aviation program at Tuskegee. With the outbreak of World War II, everyone realized it was a matter of time before the United States would be involved. As the author writes, the birth of the Tuskegee Airmen was not when the college was selected as the Civilian Pilot Training Program for blacks in 1939, rather that seed had been planted five years earlier when Robinson flew there in an attempt to convince the school’s leaders to adopt such a program. As with white America, Tuskegee officials were reluctant to agree with Robinson for varied reasons. Although he never taught at Tuskegee, his vision and accomplishments were well known and undoubtedly contributed to the success of the program.

During World War II, Robinson returned to his beloved Ethiopia to assist in the war effort. After the war, he remained and was tragically injured in a plane crash when on a mercy mission to obtain blood for a transfusion for a young Ethiopian boy. A damaged engine valve was the cause of the crash. He lingered for several weeks in a hospital before succumbing to the third-degree burns he suffered from the accident. He was buried with full military honors, and thousands came to view the body of the “Brown Condor of Ethiopia,” as he was affectionately called.

“Unlike Robinson, the Tuskegee Airmen eventually found the national spotlight to rightly earn a distinguished place in the annals of American history,” Tucker writes. “However, without Robinson’s efforts and achievements on both sides of the Atlantic, there might well have been no Tuskegee Airmen of World War II fame.”

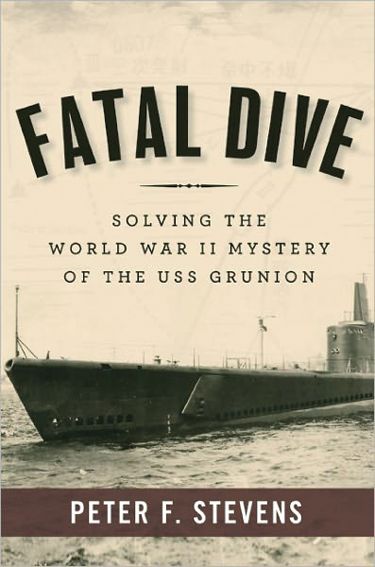

Fatal Dive: Solving the World War II Mystery of the USS Grunion by Peter F. Stevens, Regnery History, Washington, D.C., 2012, photographs, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Fatal Dive: Solving the World War II Mystery of the USS Grunion by Peter F. Stevens, Regnery History, Washington, D.C., 2012, photographs, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

Here is a great detective story that unearthed the fate of a U.S. Navy submarine, USS Grunion, and its entire 70-man crew who were lost at sea off the coast of Kiska in the Aleutian Islands during World War II. The commander of the sub, Lt. Cmdr. Jim Abele, was patrolling the icy waters searching for Japanese transports when his boat was sunk by a 3-inch shell from the Japanese transport Kano Maru, which was struck by one of Grunion’s torpedoes. When a “thin, black bar” suddenly shot up from the sea like a rifle shot and then quickly fell back into the water, and a brown liquid appeared on the water’s surface, the Japanese were overjoyed believing they had sent the enemy vessel to the bottom of the ocean. Or did they?

For 65 years, the families of the crewmembers of USS Grunion were in the dark as to the whereabouts of their loved ones. The Navy Department had said they were lost at sea and presumed dead. Abele’s widow, Kay, wrote countless letters to the crew’s families until her death in 1975. However, her sons, John, Brad, and Bruce, never lost hope and would ultimately finance a trip, costing them millions, to the frigid waters of the Bering Sea, near Kiska, to determine the fate of their father and his crew.

On August 23, 2007, a remote-operated vehicle (ROV) was dropped from the Aquila, a 165-foot commercial fishing boat, commanded by skipper Kale Garcia, who was familiar with the area. When it was finally determined that they had found the wreckage of Grunion, the next question was how she sank?

Experts examining the photos from the ROV, declassified U.S. and Japanese documents, and eyewitness accounts from the Kano Maru came to the conclusion that the MK 14 torpedo launched by Grunion has not detonated and made a circular path back toward the sub, striking her stern. The “loud thud” was heard by the Japanese sailors, but it was not the 3-inch shell they had heard, it was the boat’s own torpedo.

When Abele ordered the sub to dive, he did not realize that its stern planes were jammed in full dive. The sub buckled and imploded, sending her to the bottom. Why did the Navy hide this fact for so many years? The author contends that they were trying to cover up the fact that it was the faulty torpedo they were using during the early stages of the war.

This book is a truly moving tribute to the tremendous resolve of the Abele family, the families and friends of Grunion who, despite insurmountable odds, were finally able to uncover the mystery behind the loss of the submarine that sent 70 souls to the bottom of the ocean on July 31, 1942.

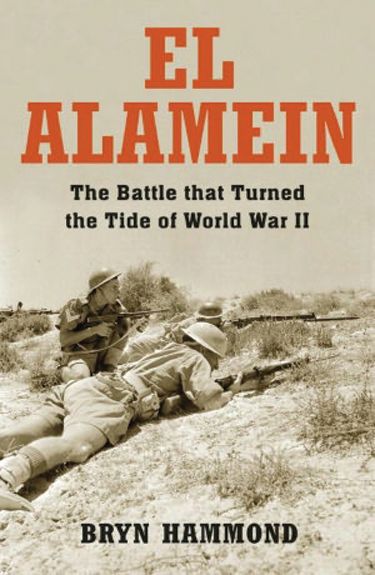

El Alamein: The Battle that Turned the Tide of the Second World War by Bryn Hammond, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 328 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

El Alamein: The Battle that Turned the Tide of the Second World War by Bryn Hammond, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 328 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $24.95, hardcover.

The author has done a superlative job in writing about a battle that has been thoroughly examined by others. He, however, brings fresh material to light about the extreme hardships faced, not only in fighting a determined foe but the harsh weather conditions as well, from actual survivors of the Battles of El Alamein and Alam Halfa from June through November 1942. It was here that British and Commonwealth troops stopped German Field Marshal Edwin Rommel’s juggernaut that was bent on seizing Egypt, giving the Nazis control of the Suez Canal and the Middle Eastern oil fields.

Hammond also writes about the relationships among the commanders of the British Eighth Army and their staffs and superiors, primarily Prime Minister Winston Churchill, who was known for meddling in military matters. Command of the British forces ultimately fell to Lt. Gen. Bernard Montgomery, who subsequently beat Rommel in one of the largest tank battles in military history.

Rommel, given the sobriquet of the Desert Fox because of his uncanny ability to appear out of nowhere and achieve victory, became something of an unbeatable superhero in the minds of many. However, the British soldiers, the author claims for the most part, had remarkable morale despite their setbacks on the battlefield.

Hammond praises the Italian Army units attached to Rommel during the campaign. Unfortunately, the Desert Fox did not think highly of them or the overall Italian commanders who he had to report to and gain approval for his actions. None of the Italian leaders “could control Rommel.”

Although the Germans had occupied “sound positions,” as one British private wrote in a letter home, El Alamein was much more than just a tremendous artillery barrage. The fighting, at times, was hand-to-hand, and the dreaded minefields took the lives of many men. In the end, the British Tommy plus New Zealand, Australian, South African, and Indian troops, won the day—and drove the German Army out of North Africa.

William D. Pawley: The Extraordinary Life of the Adventurer, Entrepreneur, and Diplomat Who Cofounded the Flying Tigers by Anthony R. Carrozza, Potomac Books, Washington, D.C., 2012, 407 pp., photographs, notes, index, $34.95, hardcover.

He has been referred to as a “mid-twentieth century cross between Indiana Jones and Donald Trump” and there is no doubt that William D. Pawley led an amazing life—from selling candy bars to sailors whose ships were docked in Havana harbor, supporting the American Volunteer Group, more commonly known as the Flying Tigers, to serving as ambassador to Peru and Brazil and advisor to four presidents —it seems Mr. Pawley did it all.

An enterprising man, even as a child, Pawley honed his salesmanship skills in Cuba and Florida. After delving into numerous business ventures, the Georgia native was bitten by the aviation bug. His reasons for hastily leaving Cuba remain unclear, but he claimed it was for “political reasons.” So, the young entrepreneur ventured to China in 1933 to make his mark in that Asian country.

Pawley’s tenure in China was full of backroom business dealings, hobnobbing with Chinese officials, and making sure that his planes from the China National Aviation Corporation cornered the market. He made many friends and as many enemies, including U.S. Army officer Claire Chennault, who would eventually head the Flying Tigers comprised of American volunteer pilots fighting the Japanese who had invaded China in 1937.

Pawley and Chennault battled for years after the war about each other’s role in creating the famed group. The author traces Pawley’s career after World War II as well. His book is a well-written and absorbing story of a fascinating individual who left his indelible mark on world history.

Two Roads to War: The French and British Air Arms from Versailles to Dunkirk by Robin Higham, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 410 pp., photographs, notes, index, $44.95, hardcover.

Two Roads to War: The French and British Air Arms from Versailles to Dunkirk by Robin Higham, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 410 pp., photographs, notes, index, $44.95, hardcover.

A former Royal Air Force pilot and teacher of military history at Kansas State University, author Robin Higham has written a factual and interesting book on the pitfalls of the Armee de l’Air, or French Air Force, during the period between the world wars and how its shortcomings, military, political, and even social, affected its performance during the early days of World War II. Higham compares the French Air Force to methods the British Royal Air Force used to emerge as an effective fighting arm. He contends that the RAF was the core of this military machine and not on the periphery, as the air force was within the French Army.

In addition to the French Air Force being relegated to a back seat role during the two decades between the conflicts, the author claims that the British business owners and entrepreneurs who were involved in the design and manufacture of British aircraft had a good working relationship with the unions, something the French lacked.

Sadly, the French were still rebuilding and “depressed by the casualties of the 1914-1918 conflict” and adopted a defensive mind-set prior to the German invasion. Aircraft of all types took on a secondary role in the French military, contributing to an ineffective defense of the country.

When the massive German blitzkrieg rolled around the Maginot Line on May 10, 1940, the country crumbled, setting up the humiliating evacuation from Dunkirk by Allied forces in June. France soon capitulated, and the country would be occupied by the Nazi invaders until 1944.

The Chaplain’s Conflict: Good and Evil in a War Hospital, 1943-1945 by Tennant Williams, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2012, 144 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

The Chaplain’s Conflict: Good and Evil in a War Hospital, 1943-1945 by Tennant Williams, Texas A&M University Press, College Station, 2012, 144 pp., photographs, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover.

Here is a unique and candid look at the inner workings of the 102nd Evacuation Hospital from the viewpoint of its chaplain, 1st Lt. Renwick C. Kennedy, a graduate of the Princeton Theological Seminary and prolific writer who chronicled his time with the unit when it served in France, Belgium, Luxembourg, and Germany. The author, Tenant Williams, interviewed Kennedy at his home in Camden, Alabama, and was given his correspondence when he passed away in 1985. Williams and his wife traveled extensively throughout Europe retracing the movements of Kennedy’s unit to write his account.

In his writings, Kennedy wrote with clarity and, above all, honesty when discussing those he served with. Not all his observations were glowing. He vividly describes the affairs between doctors and nurses, the rape of two German girls by six GIs and, interestingly enough, his dislike for General George Patton, whom Kennedy referred to as “very profane and vulgar.”

Kennedy wrote about his experiences, both good and bad, later in an article for Christian Century magazine and was severely criticized by the American Legion as being “un-American.” Despite this, he treasured his time with the 102nd Evacuation Hospital, where the majority of men did their jobs in a professional manner.

“Being with the 102nd was like going to school in reality,” he confided to Williams. “I have to say that I may have learned more with the 102nd than I did at Princeton.”

Short Bursts

Patton: Blood, Guts, and Prayer by Michael Keane, Regnery Publishing, Washington, D.C., 2012, 256 pp., notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Patton: Blood, Guts, and Prayer by Michael Keane, Regnery Publishing, Washington, D.C., 2012, 256 pp., notes, index, $27.95, hardcover.

There has been a plethora of books about the legendary General George S. Patton, Jr., but this new addition is a good overview of his life. A man of many contradictions—a very religious yet profane individual—he became a living legend. From his days at West Point to the punitive expedition to hunt down the Mexican bandit Pancho Villa where he received his baptism of fire, to his grievous wound in World War I, to his exploits in Europe during World War II, Keane traces Patton’s life until his untimely death due to a car accident in December 1945.

Patton was cheated out of his wish of being killed in battle. He told his wife from his hospital bed that he “wasn’t good enough,” before succumbing to his injuries. If he had lived, Patton would have almost certainly been paralyzed, a fate for “Old Blood and Guts” that would have been worse than death.

Intact: A First-Hand Account of the D-Day Invasion from a 5th Rangers Company Commander by Maj. Gen. John C. Raaen, Jr. USA (Ret.), Reedy Press, St. Louis, MO, 2012, 176 pp., photographs, index, $18.00, softcover.

Intact: A First-Hand Account of the D-Day Invasion from a 5th Rangers Company Commander by Maj. Gen. John C. Raaen, Jr. USA (Ret.), Reedy Press, St. Louis, MO, 2012, 176 pp., photographs, index, $18.00, softcover.

Retired Major General John Raaen has written a detailed blow-by-blow description of what transpired from his company’s initial landing on Omaha Beach on June 6, 1944 to the relief of the Ranger contingent atop Pointe du Hoc the following day. Interspersed between his own story of the 5th Rangers, Raaen received eyewitness accounts of what transpired in adjacent areas from those who fought there. Adding the two together gives the reader a complete story of what the Rangers and elements of the 116th Infantry Regiment endured when they faced a determined dug-in German Army.

Raaen, who received a Silver Star for his actions during that period, lists the Distinguished Service Cross (DSC) recipients as well. One fascinating sidebar to the book is the brief biography of the battalion chaplain, Father Joseph Lacy, a Roman Catholic priest, who was awarded a DSC for continually exposing himself to enemy fire on the beachhead as he dragged the wounded to safety, prayed over them, and gave last rites to the dying.

This is a gem of a book that gives readers an excellent viewpoint from one Ranger who served on Omaha Beach during the “Longest Day” of World War II.

P.O.W.: A Sailor’s Story by Ralph C. Poness, Vantage Press, New York, 2012, 134 pp., $16.95, softcover.

This is a riveting story of one sailor’s hell as a prisoner of the Japanese during World War II. A gifted athlete, Ralph Poness joined the Navy in 1937 to see the world. His travels took him to the Far East as a crewmember on the destroyer USS Pope. Transferred to the U.S. Navy Yard at Cavite, Philippines, ironically so he could have the opportunity to play baseball, Poness was captured by the Japanese when they invaded the islands in the spring of 1942. He tells of his harrowing experiences when traveling to the POW camp at Cabanatuan and then a terrifying nine-day sea voyage to Japan itself, where the men were to be used as slave labor for the enemy’s war machine. After his death in 2002, Poness’s son eventually gathered his father’s manuscripts and published his story. It is indeed a moving tribute to a man who endured so much for his country.

D-Day Victory with the Men and Machines That Won the War by Stephen Bull, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 272 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover.

D-Day Victory with the Men and Machines That Won the War by Stephen Bull, Osprey Publishing, Long Island City, NY, 2012, 272 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $25.95, hardcover.

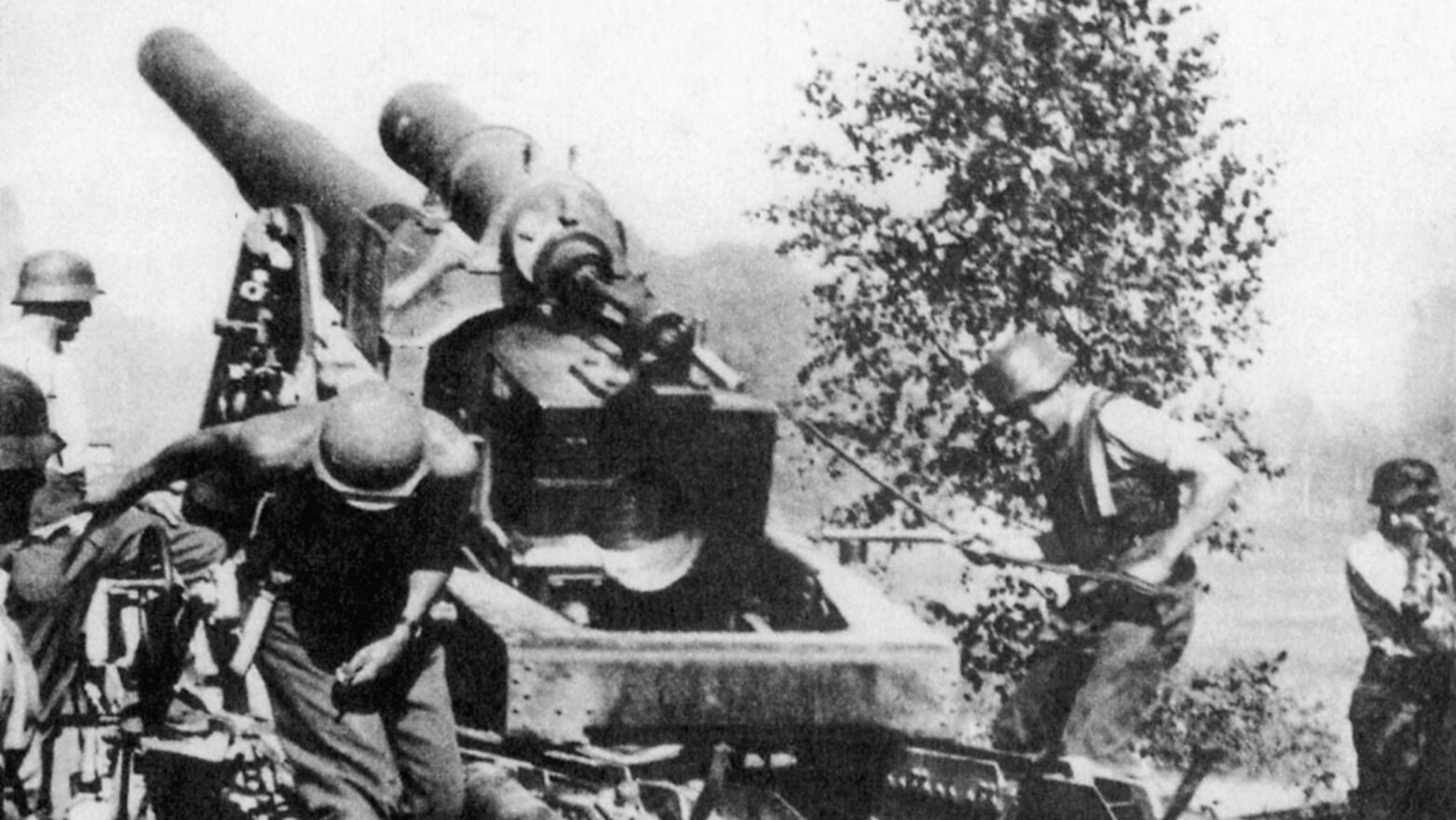

This book focuses on the D-Day landings on June 6, 1944, until Germany’s surrender in May 1945. It is told by the Allied soldiers who lived through it with the equipment they carried or operated to achieve that victory. Everything from tanks, bazookas, and artillery to flamethrowers and more are discussed. The book contains numerous color as well as black and white photographs, while detailed maps and other illustrations accompany the text. More than 80 interviews from the actual participants are also included and add a dimension of realism to the story. The book’s final comment on the Allied veterans is most revealing when veteran Jim Tuckwell notes, “I think they were on this earth to do what was right.”

Nazi Steel: Friedrich Flick and German Expansion in Western Europe, 1940-1944 by Marcus D. Jones, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 192 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

Nazi Steel: Friedrich Flick and German Expansion in Western Europe, 1940-1944 by Marcus D. Jones, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2012, 192 pp., notes, index, $29.95, hardcover.

The Nazi war machine needed extensive amounts of war matériel to fulfill Hitler’s dream of a world ruled by the Third Reich. To accomplish this goal, Friedrich Flick, a German industrialist, assisted by supplying the Nazi government with a wide variety of items such as steel, coal, munitions, trucks, airplanes, and more. He amassed a huge fortune selling material to the Nazis. In 1941, with German occupation of the Lorraine region in France, Flick obtained the massive and lucrative Rombach steel works and immediately went to work to manufacture war equipment.

The author does a good job examining the relationship between Flick and other German business magnates within the Nazi regime. He also focuses on the German economic policies in the occupied territories during the war. After the conflict, Flick was tried at Nuremberg for using slave labor and was sentenced to seven years in prison but was released after serving just three years.

Despite losing most of his assets, Flick rebounded and became a multi-millionaire by investing in automobile plants and paper mills. He died in 1972 and, according to the author, he was “by default institutionally more complicit than most other industrialists” who were helping to supply Hitler’s armed forces for world domination.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments