By Mitch Yockelson

On Tuesday, June 6, 1944, at nearly three in the morning, Chicago-native Lieutenant John E. Peters safely landed Snooty, his Douglas C-47 Skytrain, on the massive 5,800-foot runway at Greenham Common airfield in southern England.

A few hours earlier, around 10 p.m., Peters had taken off from there with a stick (an Army Air Corps designation for a planeload of paratroopers) of 18 heavily armed paratroopers from 3rd Battalion, 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st “Screaming Eagles” Airborne Division—a unit that had yet to see battle. They were led by Lt. Col. Robert G. Cole from San Antonio, Texas, the senior officer aboard—and future Medal of Honor recipient.

Upon Snooty’s return to Greenham Common, the plane was empty of paratroopers. Cole and his men had jumped into a pre-assigned Normandy drop zone (DZ). Wright Bryan was the lone passenger on Peters’ C-47.

A civilian war correspondent who reported on the European Theater for both the Atlanta Constitution and NBC Radio, Bryan was invited to fly with Cole’s men and witness their jump into Normandy. Then he would fly back to England and, after Prime Minister Winston Churchill, General Dwight Eisenhower, and the King of England officially announced the commencement of D-Day, Bryan would broadcast a report on his observations of the paratrooper drops.

Before Snooty left for Normandy, Bryan watched Cole’s paratroopers adjust their packs, put on their Mae Wests (B-4 life jackets nicknamed for the Hollywood starlet inflated with compressed air, giving them an impressive torso profile) and chutes, and climb into the planes. Each man was so heavily loaded that he had to be pushed from behind and pulled from above to mount the steps into the plane.

Bryan boarded Snooty last and spoke with some of the men, scribbling down their comments with pencil on sheets of paper or in his small pocket diary. Private Robert G. Hillman of Manchester, Connecticut, sitting farthest forward on the port side, proudly told the war correspondent, “I know my chute’s okay because my mother checked it. She works in the Pioneer Parachute Company in our town and her job is giving the final once-over to all the chutes they manufacture.” Before joining the Army, the blond, blue-eyed paratrooper had also worked for a time at Pioneer. (Private Hillman was wounded on June 8, but quickly recovered, and fought with the 502nd PIR until the war ended and he returned home.)

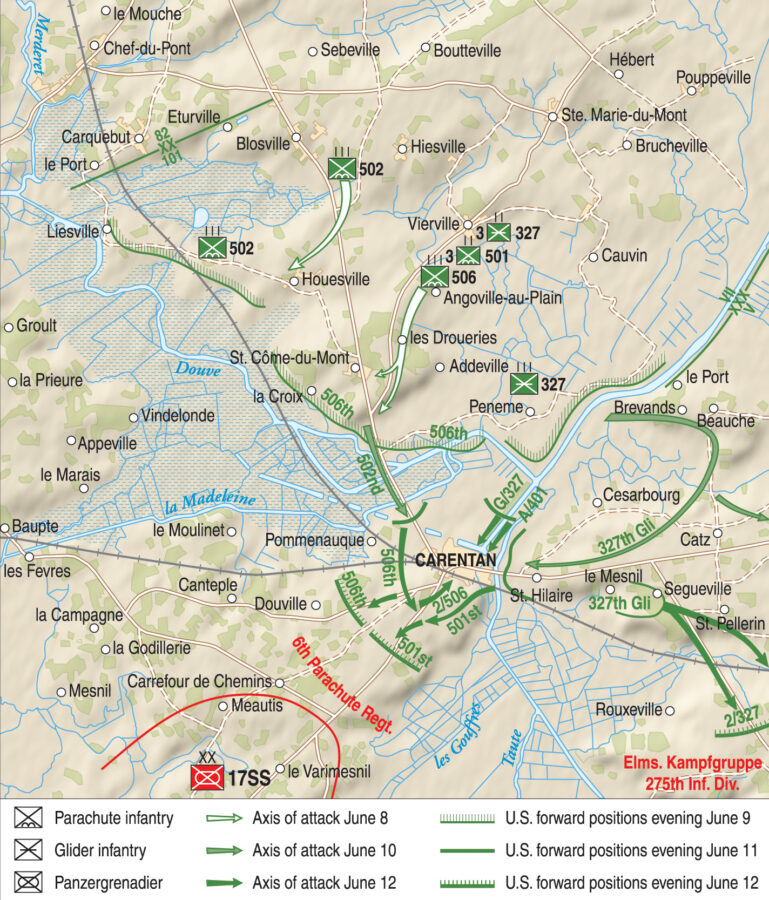

On D-Day, Cole’s battalion had been placed in reserve, but a couple of days later they would take part in the division’s first and most significant operation—the capture of Carentan, a vital crossroads town of about 5,000 people located on the Douve River, between the two American invasion beaches, code-named Utah and Omaha.

On the morning of June 7, 1944 (D-Day+1), Colonel Robert Sink, commanding the 506th Parachute Infantry Regiment, spearheaded the day’s attack. The 506th’s 1st Battalion would strike at the railroad bridges across the Douve River to keep German armor from passing over them and threatening the American flank. This operation prepared the 101st for an assault on Carentan.

Reuters correspondent Bob Reuben remembered how much in awe the Screaming Eagles were of the battle for Carentan. Before D-Day, in the marshaling area back in England, staff officers stressed that the town “was the channel through which Germany could pour its hordes upon our landing forces while they struggled through the water and sought a shaky foothold on the beaches.”

Before the war, Carentan had thrived on dairy farming. On the out skirts of town, cows grazed on the lush greenery. Now, American forces needed to take the town in order to consolidate the beachheads at Omaha and Utah. Although only a small city of 4,100 civilians, Carentan was larger than any other community in the lower Cotentin Peninsula. Straddling the main highway from Cherbourg to Caen and St. Lô, the double-tracked railroad from Paris to Cherbourg cut through the center of town, making it strategically important for German communications.

Between his 1st Battalion (under Lt. Col. William L. Turner) and the 2nd Battalion (Lt. Col. Robert L. Strayer), Sink had roughly 525 men for the operation. Sink also had about 40 men from the 82nd Airborne Division, some 326th Engineers, and a battery from the 81st Airborne Anti-Aircraft Battalion carrying eight six-pound antitank guns.

This was a far greater concentration than other Screaming Eagle regiments. Many of the 101st paratroopers, such as division commander Maj. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor, had landed far from their DZs. A number of Sink’s paratroopers had missed the first day’s fighting, trickling into regimental headquarters on D-Day afternoon, later that night, and well into the predawn hours of June 7.

Master Sgt. Lloyd E. Willis, from Sink’s regiment, was among the cluster of latecomers. Willis dropped into an orchard and didn’t realize that beyond the tall, thick hedgerows looming all around him, the 506th PIR’s assembly away was only 400 yards away. Willis stripped off his parachute harness and set out in the dark to find other paratroopers. He wandered aimlessly for several hours, becoming trapped within the maze of tall vegetation, seldom seeing “more than one hundred yards in any direction.”

Eventually, Willis stumbled upon a group of 25 men, including some from his regiment’s Headquarters Company. The others belonged to various 82nd Airborne units. This mixed bag of lost paratroopers was drawn into a couple of small skirmishes.

“You go along and join a group,” Wills wrote. “The group goes along and is fired upon. Then you engage. Everybody has to wait until the road is clear again. The larger the group, the harder it is to get by without fighting.” Willis eventually reached Culoville at 10:30 a.m. on June 7.

Captain Laurence Critchell sympathized with the plight of Willis and other paratroopers lost in the dense landscape of Normandy. In his history of the 506th, Critchell wrote, “for a man to crawl through the hedgerows was almost impossible.” The “twisted roots,” Critchell recalled, “were close together and immovable.” A soldier could try and climb over the hedgerows, but, if he did, “it was unlikely that he would be alive to reach the ground on the other side.”

At 4:30 a.m., Sink’s paratroopers started their advance toward the railroad bridge. As Critchell noted, this attack would be the first attempt by the 101st “to act with forces in excess of the scattered Indian bands” that had done the fighting on D-Day. Sink accompanied his regiment’s 1st Battalion down the road from Culoville to Vierville. Right from the start, German snipers harassed the men, firing at them from the front and flanks.

Sink made a brief stop at Vierville to clear the houses of enemy troops. General Taylor arrived in the town, and while he conferred with Sink, they could see several hundred troops, thought to be German, about 2,000 yards to the southeast.

Bunched together, they would make an easy target, Sink thought, but he hesitated to fire on them until he was certain they were enemy. He sent out a patrol to get a better read on the soldiers, but before the patrol came back, the column of supposed enemy troops was out of sight.

Before departing Vierville, Sink split his regiment so that the 1st Battalion headed toward Beaumont and the 2nd veered left in the direction of Angoville-au-Plain. Neither battalion got very far. German machine-gun and small-arms fire put a halt to the advances.

A platoon of Sherman medium tanks from Company A, 746th Tank Battalion, which had come ashore at Utah Beach right before noon the previous day, came to their aid. Still, 1st Battalion continued to take enemy fire on its right flank from German soldiers who hid behind trees and hedges on a ridge that paralleled the road. Eventually, 1st Battalion made its way into Beaumont, but two enemy counterattacks stalled any further advance.

Support from a company of paratroopers from 2nd Battalion and a platoon of M5 Stuart light tanks from Company D, 70th Tank Battalion, freed 1st Battalion to push ahead to a crossroads about 500 yards east of Saint-Côme-du-Mont. After firing at the Germans, one of the tanks ran out of ammunition and its commander, Lieutenant Walter T. Anderson, ordered it back to the rear to reload.

Instead of returning by the same route, which was through the hedges and into a field, the tanker took the road and rolled up in front of a house being used as a German aid station. An enemy antitank crew was on the property: one blast placed an armor-piercing shell through the tank’s turret.

Private Donald Burgett, a paratrooper with the 506th PIR, watched in horror as “the small tank erupted in a violent explosion and started to burn.” The tank crew died instantly. “We could smell their flesh cooking in the flames,” Burgett later wrote, “along with the heavy, oily smoke.”In the explosion, [a crewman’s] body was thrown half out of the tank’s turret. For several days, the tank with the corpse in full view remained on the road. Soldiers who passed by this intersection referred to it as “Dead Man’s Corner.” (For many years it was believed that Lieutenant Walter T. Anderson was the dead tanker; an investigative story published in WWII Quarterly, Spring 2020, identified him as either Aaron D. Curry or Anthony I. Tomasheski.)

It being too dangerous to remain in the open, 1st Battalion moved to higher ground east of the town, but the nearby enemy strength made this position equally treacherous. Sink ordered 1st Battalion to withdraw back to Beaumont, and he would make another stab at Saint-Côme-du-Mont the next morning.

At dawn on June 8, the new attack on Saint-Côme-du-Mont strengthened to four battalions. On the right, Sink’s 1st and 2nd Battalions headed directly from Beaumont to the town. The 3rd Battalion, 501st PIR, advanced from the southeast at les Droueries to the main highway south of Saint-Côme-du-Mont. To the left, 1st Battalion, 401st Glider Infantry, headed from the east of les Droueries. As the entire force of paratroopers descended upon Saint-Côme-du-Mont, the glider men would slant off to the south, head down the highway, and blow up the causeway bridge to prevent German reinforcements.

Lt. Col. Julian Ewell’s 3rd Battalion, 501st PIR, easily cleared les Droueries and moved quickly toward an intersection east of Saint-Côme-du-Mont. Ewell thought he saw German troops withdrawing from Saint-Côme-du-Mont and took his men south along the Carentan Highway to capture the causeway and the bridges. Just when the men moved on to the highway, they were hit by small-arms, machine- gun, and antitank fire coming from buildings near the first bridge and 88mm shelling being lobbed in from Carentan.

Just as Ewell pulled the battalion back to the highway, a German counterattack hit him. Ewell’s men drove back the enemy, but the Germans were still in force on a small hill to the west. Ewell dug his men in on an east/west line facing north. The Germans attacked the position five times, almost piercing the American line on each occasion, but Ewell’s men hung tough and never wavered. The enemy withdrew, leaving a clear route into Saint-Côme-du-Mont.

Now General Taylor’s 101st could concentrate on destroying the causeway bridges that led to Carentan.

Taylor ordered the main attack on Carentan to commence on June 10, 1944, with two crossings over the Douve River. His left wing would start at 1 a.m. and cross in the vicinity of Brevands. A detachment from this force would link up near the Vire River Bridge southwest of Isigny with V Corps coming from the direction of Omaha Beach. The 101st’s right wing would cross the causeway northwest of Carentan, bypass the city, and attempt to seize Hill 30 to the southwest.

By taking Hill 30, the American paratroopers would have a clear view of the main German escape route from Carentan. As the operation unfolded, the left and right wings would coordinate and form a ring around the city and then press into the city itself.

Now, with Saint-Côme-du-Mont no longer a threat, the 101st’s right wing was ready to attack with Lt. Col. Cole’s 3rd Battalion, 501st PIR. His force would approach Carentan over a four-and-a-half-mile asphalt causeway, about 40 feet wide with dirt shoulders, that elevated from six to nine feet above the marshes and crossed over the Douve and Madeleine rivers, as well as two Douve canals. Cole would have no protection should his men take fire from the front or flanks.

Shortly after midnight, Cole’s battalion started out but was soon ordered to halt as engineers—deployed to repair Bridge 2—came under heavy fire. A patrol sent to investigate determined that a stronger-than-expected German force with mortars and machine guns was positioned on the highway and on higher ground directly south and west of the highway.

Cole would now have to attack in the afternoon with artillery support from two field-artillery battalions. At noon on June 9, the engineers had still not finished repairing a 12-foot gap on Bridge 2. Cole and three of his men improvised a footbridge to allow his battalion to start crossing single-file in the middle of the afternoon. Cole’s force was then repeatedly hit by the projectiles of an 88mm gun fired from Carentan, but there were no casualties, and the battalion continued along at a steady pace by keeping low and crawling along an embankment.

Three hours down the highway, when the last of Cole’s battalion had crossed three of the bridges and most of his men were over Bridge 2, the Germans opened fire from two directions—the hedgerows and a large farmhouse to their right front. Cole’s men on point tried ducking in the ditches, but as they attempted to advance, an enemy machine gun perched behind a hedgerow only 100 yards away blasted into the ditches and struck three men, forcing the group to withdraw.

Now the entire battalion was under small-arms fire and couldn’t maneuver to either flank. They were a totally exposed, long, thin column. The only way to advance was to send one man at a time through the heavy steel fence, known as a “Belgian Gate,” at Bridge 2. It stretched almost completely across the bridge, and the men would have to slip under an opening that was only about 18 inches wide. This would be attempted, of course, under heavy enemy fire.

American artillery from the 377th Field Artillery Battalion (with two captured German guns); the 907th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, armed with 12 pack-howitzer 75mms; and the 65th Armored Field Artillery, with its 18 self-propelled 105mm guns, helped neutralize the German guns. A portion of Company G, which led Cole’s battalion, deployed to the left of the bridge and provided cover fire while the remainder of the unit tried squeezing through the narrow gate opening. Only six men got through; the seventh was wounded.

The company temporarily ceased its attempt to cross and instead set up a fire position with mortars, but the small bombs made little impact. German fire kept coming, and casualties mounted within the American ranks as the men had nowhere to take cover on the bare ground.

Now, at 4 a.m. on June 11, Cole ordered the 3rd Battalion to attack, using the darkness as cover. His plan worked. Three companies made it across Bridge 4, and the battalion deployed on both sides of the highway. Because there were so many casualties along the causeway that day, the Americans named it “Purple Heart Lane.”

Scouts were sent out to determine the main source of enemy strength. It was the large farmhouse beyond Bridge 2, well defended by mortars, machine guns, and rifles. American artillery concentrated on the building, to little effect. Cole decided that his only option was to rush the house, so he ordered a bayonet charge. Cole called to his second-in-command across the road, executive officer Major John P. Stopka, to have the order passed along.

Even though it was still dark, Cole ordered artillery units to put down smoke in a wide arc around the farmhouse to conceal the attack. “What made the job so difficult, I believe,” Cole explained afterward, “was that hedges were filled with snipers … Artillery was not heavy enough to knock them out unless you got a direct hit … The shells burst above them.” The Germans also made practical use of an orchard behind the house by using woodpiles to climb up into the trees and hide themselves in the branches.

At 6:15 a.m. on June 11, as the artillery laid down fire, Cole blew his whistle, drew his Colt .45 pistol from its holster, and charged forward. But he was practically by himself. Instead of the 250 men who should have been right behind him, only 20 left cover to follow him; another 10 were behind Major Stopka. The other 200 men, spread all around, had not heard the order for a bayonet charge.

Some troops from Company G ignored Cole and Stopka for good reason: they were busy tangling with enemy soldiers in a meadow east of the highway. Some of the men in Company G didn’t hear Cole’s whistle, but when they realized what was happening, they took off to catch up with the others.

None of them had charged an enemy position before, and their inexperience showed. They bunched up while running across a ditch into a field raked with fire to the east of the farmhouse. Several times Cole had to stop, “waving both arms at them,” trying to “get them to fan out.” He fired his Colt .45 “wildly” in the general direction of the farmhouse, while at the same time wondering, “Goddam, I don’t know what I am shooting at, but I gotta keep on.”

The first men to reach the farmhouse found it abandoned. The German soldiers had withdrawn to the west on higher ground and were entrenched in rifle pits and concrete machine-gun emplacements strategically placed along a hedgerow and pointed at right angles toward the road.

Cole’s men refused to be deterred. With sheer momentum, they charged the Germans and wiped out their position with bayonets and grenades. Cole had hoped to keep the initiative going and take advantage of the enemy’s disorganization, but this was asking too much of his men. All the paratroopers in his battalion had found their way across the causeway and assembled in a field near the farmhouse.

For his bravery that day in leading the bayonet charge, fully exposed to enemy fire, Cole would later be awarded the Medal of Honor in October 1944, the only soldier with the 101st Airborne to receive such acclaim. (Unfortunately, Cole would be killed on September 18, 1944, by an enemy sniper in Operation Market Garden, so his mother accepted the medal on his behalf on the Fort Sam Houston parade ground where he had played as a child.)

The companies and platoons were mixed, and many of the soldiers had been torn up by artillery and small-arms fire. Cole sent a runner to Lt. Col. Patrick J. Cassidy’s 1st Battalion, 502nd PIR, with a message requesting he come up, pass through his battalion, and continue attacking south from Hill 30 through the hamlet of la Billonerie.

Cassidy’s battalion was north of Bridge 4 when Cole’s message arrived. Crossing the bridge under heavy fire, Cassidy deployed the men across the field toward the farmhouse, but his men were in just as bad shape as Cole’s.

So, instead of relieving 3rd Battalion, Cassidy stayed put and placed his men to the right of Cole’s battalion. More men arrived to defend the right flank, where a few German troops had remained. Another small group appeared and set up a machine-gun position behind the farmhouse that covered all directions.

Even with the ground heavily defended by a mix of paratroopers, Cole remained concerned. He was unaware of the situation on his flanks: his communications had failed, and he didn’t trust the artillery support. The men had their backs to the Douve River and had no rear area and no reserves close by. The artillery observers couldn’t see where their shells were landing because of the dense hedgerows and had to adjust their fire unreliably by sound.

Cole’s worries turned out to be justified. In the middle of the morning, the Germans counterattacked. A large enemy force rushed through the orchard and placed American paratroopers south and east of the farmhouse in peril, but the machine guns that were placed south of the house repelled the assault. There was still sporadic firing throughout the morning, but around noon regimental headquarters sent a message that the enemy had requested a truce. In reality, that message had been misunderstood.

Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, who had been directing the operations for the 101st, had requested the truce for his own men so that casualties could be removed. The 502nd regimental surgeon, Major Douglas T. Davidson, escorted by two Germans, had walked through enemy lines to ask the military commander in Carentan to allow a brief lull in the fighting to evacuate the wounded.

But Davidson wasn’t allowed to speak to the German commander, and as he returned to Bridge 4, the enemy launched an all-out assault with what seemed like every gun in its arsenal—small arms, machine guns, mortars, and artillery.

Cole asked regimental headquarters for permission to return fire but was told to wait until definitive word was received from Davidson. Cole’s men took matters into their own hands, however, and retaliated with their arsenal. They were certain, having observed movement by the Germans during the truce, as well as the accuracy of the enemy guns, that the interlude had been used to strengthen German positions for an attack.

Cole’s men were at a breaking point. German fire kept coming and became more intense the longer the attack continued. Observing the battle from a second-floor window in the farmhouse, Cole told regimental headquarters that his only option was to withdraw, and he requested cover fire and smoke when the time came to vacate the positions. His artillery observer, Captain Julian Rosemond, tried to send the message, but his radio was out of order.

Throughout the day, the battle see-sawed. Just when the exhausted Americans believed the Germans were finished, they would counterattack. By afternoon, what remained of Cole’s battalion was barely holding on in and around the farmhouse. Cole stood near a window and observed the fighting. Without artillery support, there was little chance of driving off the enemy.

But that changed when Rosemond finally reached the artillery command post and, a brief time later, the German fire subsided. The 506th PIR had increased its artillery fire, lobbing shells over the farmhouse into a field where the enemy had been positioned. American patrols determined that the enemy had fled, likely to Carentan. Around eight that evening, 2nd Battalion arrived and relieved the 1st and 3rd Battalions.

Enemy defenders blocking the road to Carentan from the north were no longer a threat, but the 502nd was too exhausted to continue the attack. Carentan would have to wait another day.

Taking the city of Carentan was Maj. Gen. Maxwell Taylor’s last major objective in the Normandy Campaign, and his most important. The only sound approach to Carentan was down the slope from Saint-Côme-du-Mont and along an exposed causeway supporting the main road. Carentan was mostly defended by Oberst (Colonel) Friedrich von der Heydte’s veteran German 6th Parachute Regiment, which had arrived in Normandy about a week before D-Day.

Taylor’s men launched the attack on Carentan in the early morning hours of June 10 from two directions. The 502nd PIR advanced from the south along the Cherbourg Road, while the 327th Glider Regiment crossed the Taute River to strike from the northeast.

At 1:45 a.m., a brief artillery and mortar bombardment preceded the advance of the 1st Battalion, 327th, across the Taute. Soon after, the glider troops tangled with Germans trying to block their advance. The 3rd Battalion of the 502nd PIR had commenced its southeast movement along the causeway road toward Carentan until it met heavy resistance from the 6th Parachute Regiment, firing from behind hedgerows and farm buildings.

At 6 p.m., German bombers struck one American company of the 502nd, killing and wounding scores of Taylor’s men. By nightfall, two more glider battalions were across the Taute River. The next morning, the glider soldiers renewed their attack southwestward but were stopped cold on the northern outskirts of Carentan.

Early the next morning, June 11, a battalion of the 502nd renewed its attack under cover of a smokescreen. Reinforced by another of the regiment’s battalions, hand-to-hand fighting ensued for almost six hours. Because the casualties began piling up, Taylor had his officers in the field negotiate a truce at noon to collect the dead and wounded. Taylor exploited the opportunity to send a message to Colonel von der Heydte to offer him a chance to surrender. Strict orders from Hitler to hold Carentan at all costs meant that Heydte couldn’t even consider Taylor’s offer.

Immediately after the truce expired, the Germans repeatedly counterattacked until 10:30 p.m., forcing all three battalions of the 502nd PIR to withdraw under cover of artillery and mortar fire. By late afternoon on the next day, June 12, the Germans had run out of ammunition, so von der Heydte ordered his troops to abandon Carentan under the cover of darkness.

Around midnight on June 11, however, as the Germans began pulling out of Carentan, Brig. Gen. McAuliffe’s men pelted the enemy with large artillery, naval gunfire, and air power. Six hours later, McAuliffe’s firepower had cleared the town of Germans. Snipers continued firing, but the jubilant French citizens came out of hiding to greet the American liberators, skillfully uncorking the hidden bottles of wine that hadn’t fallen into enemy hands.

Two days later, on June 13, Major John J. Maginnis, a 50-year-old World War I veteran and coal dealer from Worcester, Massachusetts, led Civil Affairs Detachment C2B1 into Carentan. Civil Affairs detachments were charged with keeping order in the occupied towns and cities. Their interactions with civilians could be friendly one day, hostile the next.

One of 50 Civil Affairs detachments assigned to the various corps and divisions under General Omar Bradley’s First Army, Maginnis’ detachment was the first to operate in France after the War Department assigned it to the 101st Airborne. Colonel David Marcus joined Maginnis as an observer. His job was not to assist or interfere with Maginnis but to serve as the Pentagon’s keen eyes and ears in order to report back to Washington on the effectiveness of managing civil affairs.

Maginnis and Marcus entered Carentan on June 13 at 11:00 a.m., where the situation was still hostile. The German 17th SS Panzergrenadier Division mounted a heavy assault to overtake the 101st by way of the Carentan-Baupte-Périers Road. The Americans were overrun by German infantry armed with self-propelled guns, but Colonel Robert Sink’s 506th PIR managed to hold on until relief came from tanks, halftracks, and heavy guns manned by an element of the 2nd Armored Division.

Even though Carentan was a war zone, Maginnis and Marcus drove near the cattle market, where they heard rifle, machine-gun, and mortar fire. American soldiers taking cover in doorways yelled and waved for the party to quickly get out, but they refused. Maginnis asked an officer what was going on. “The krauts have counterattacked,” he warned, “and things don’t look good.”

The two men made it through the rubble to the damaged Hôtel de Ville—city hall. The town looked every bit a war zone: German bodies, destroyed equipment, and rubble clogged the streets. The civilians who remained during the fighting were left with no water or electricity, rotting garbage, and decaying animals that filled the air with a nauseous stench. Despite Carentan barely being habitable, the Germans wanted to reoccupy it.

Maginnis and Marcus remained for several hours until a shell hit the middle of the road they were on. One of Taylor’s staff officers, Colonel Bryant Moore, ordered them to withdraw to Sainte-Marie-du-Mont, about a mile to the rear. Moore explained, “I want to recheck the situation. You’re no good to me dead and I certainly don’t want to have to run Carentan myself.”

On their return to Carentan, Maginnis and Marcus stopped at the crossroads by Saint-Côme-du-Mont, the crossroads known as Dead Man’s Corner. Because of the constant shelling, they agreed to walk the several miles back, but a jeep carrying Maxwell Taylor approached and slowed down. The two men saluted the general. Marcus, who had been at West Point at the same time as Taylor, turned to Maginnis and said, “If he lives long enough, there goes a future Chief of Staff.” (He was prophetic; after the war Taylor became the fifth Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff.)

On June 14, the 101st drove off the final German counterattack—Carentan and the link between Omaha and Utah were now secure.

No longer worried about German shelling, the Civil Affairs detachment set up its headquarters on the second floor of the Hôtel de Ville. The building had a long history, including as an Augustinian nuns’ convent before being taken over by the local government. The detachment’s temporary office had an American flag on an end wall and was furnished with, according to McGinnis, “captured German stuff and not too good.”

Through three windows, each missing its glass, the crew could look out into what was once a small garden but was “now a jumble of trenches and shell holes.” Artillery shelling had destroyed much of the building, although the southwest section containing the public offices was useable. Curfew hours were set from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m.

That afternoon, Maginnis and Taylor met for about 20 minutes. The 101st commander “cross-examined” him with “impressive, probing questions” on how Civil Affairs planned to work his troops. Maginnis responded that his immediate concerns were disposing of the dead cattle and other animals, preventing contamination of the water supply, and keeping the narrow and crowded roads open for military traffic.

On June 15, as the 506th PIR’s 3rd Battalion left Carentan, Private Harold Stedman, one of the “Filthy Thirteen,” took special notice of the Carnation milk factory that lay in ruins. First led by Lieutenant Charles Mellen, Stedman’s unit had been trained as a demolition team tasked blowing up bridges over the Douve. After Mellen was killed on D-Day, Sergeant Jake McNiece took command of the unit. McNiece, who was half Choctaw Indian, encouraged the other paratroopers in the unit to wear war paint and cut their hair Mohawk-style.

Stedman stepped out of the column and plucked some labels with the Carnation logo and placed them in his pack to give to his parents; before the war, Stedman had worked at the Carnation plant in Massachusetts. Taylor concluded the meeting by telling Maginnis, “I am satisfied that you know what you are doing and have the situation under control.”

Taylor and Maginnis convened a meeting with city officials and the new mayor, M. Joret, an “old, crippled man” with a white beard who dressed in black and walked hunched over with help from a cane. Joret had replaced the previous mayor, Dr. Caillard, who was killed by a bomb dropped by an American plane (Joret’s Christian name and that of his predecessor are lost to history).

Speaking perfect French in his clipped bass, Taylor apologized to the group for the damage and mortality that war brings to local places and asked the officials to give all possible assistance and cooperation to the division. Peace and order returned to Carentan.

Maginnis and Marcus quartered in the eastern section of the city in a building owned by a brick manufacturer “of some substance in the community.” They shared the same room, sleeping on ancient cots. They drew water from a public hand pump and used a latrine in a palm garden to the rear of the building.

On June 19, no longer worried about a counterattack, the paratroopers were treated to their first movie since arriving in France. Andy Hardy’s Blonde Trouble, starring Mickey Rooney, was shown at the Jeanne d’ Arc Theatre, which had been run by German soldiers during their occupation of Carentan. Just released, the film provided comic relief for the battle-weary soldiers as clueless Andy was alternately flirted with or slapped by a blonde (Bonita Granville) on a train.

That evening, a brawl broke out between some of the Screaming Eagles and First Army military police. Shooting, fighting, and destroying property were fueled by large amounts of wine and Calvados, the local spiced brandy made from apples. Resentment had been building among Taylor’s men toward the constabulary, and now it boiled over. Their thinking, according to McGinnis, was “It’s our town, and no outsiders are going to tell us how to act here.”

Some of Taylor’s staff stepped in to prevent serious injuries or even deaths. The general took a hard line to prevent further outbreaks: he established curfew at 11 p.m. and limited the sale of alcohol.

At the end of June, General Lawton Collins withdrew Maxwell Taylor and the 101st from Carentan and removed the forces north to Cherbourg for occupation duty. The Screaming Eagles had done their part—and more—to ensure the D-Day victory. Soon returned to England to rest and refit, they would not be called upon again for combat until September—and the ill-fated Operation Market Garden.

Mitchell Yockelson lives in Annapolis, MD, and is the author of The Paratrooper Generals: Matthew Ridgway, Maxwell Taylor and the American Airborne from D-Day through Normandy

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments