By Al Hemingway

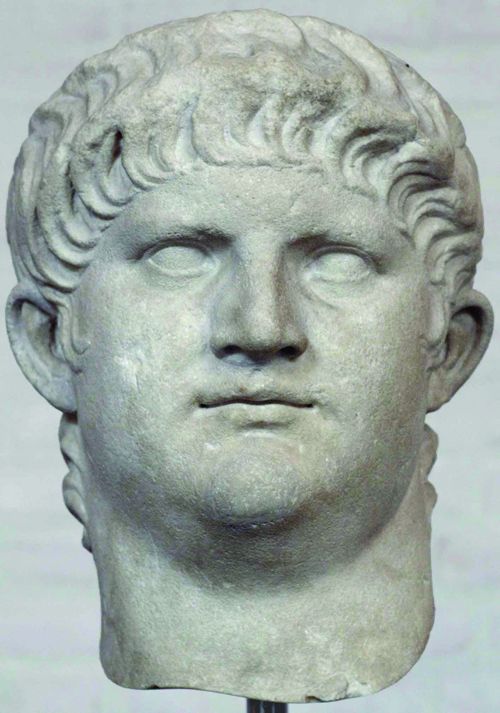

The image most people have of the Roman emperor Nero is of him perched at the summit of the Palatine hills, strumming his lyre while Rome is engulfed in flames. This impression has been accepted by many historians as fact, and Nero has even been accused of purposely starting the fire and then conspiring to place the blame on the Christians.

In his new book, The Great Fire of Rome: The Fall of the Emperor Nero and His City (Da Capo Press, Cambridge, MA, 2010, 248 pp., maps, notes, bibliography, $25.00, hardcover), Australian author Stephen Dando-Collins gives us an entirely different view of the events that led to the cataclysmic inferno that engulfed Rome on the evening of July 19, ad 64.

Whether intentionally set or merely an unforeseen mishap, the blaze ignited that evening. The day had been extremely hot, and people were streaming into the city for the Ludi Victoriae Caesaris tournament, set to begin the following morning. The fire, fueled by the summer winds, quickly spread. For the next week, flames consumed thousands of rickety wooden structures that were crammed together in the city.

Despite persistent rumors that Nero himself was arsonist, the emperor was not even in Rome when the fire started, but at his palace in Antium. He quickly returned and personally organized efforts to extinguish the fire. He also opened the Field of Mars and his personal gardens to the thousands of homeless citizens who had to flee the fire, and ordered that food and other supplies be brought into Rome. Yet despite these humanitarian efforts, reports still buzzed throughout the city that Nero had wanted Rome destroyed so that he could construct a newer, more modern capital, named after himself, to be called Neropolis.

There has never been any concrete evidence that Nero started the fire. Dando-Collins closely examines the intricate conspiracy that, he believes, would prove to be the ultimate downfall of the young emperor. Many people behind the scenes were jealous of Nero’s artistic accomplishments and his visionary plans for a newer, more modern Rome. He had already instituted a strict building code, and in spite of the severe criticism levied against him for his engineering ideas, the Corinth Canal, built after his death, followed his original design.

There has never been any concrete evidence that Nero started the fire. Dando-Collins closely examines the intricate conspiracy that, he believes, would prove to be the ultimate downfall of the young emperor. Many people behind the scenes were jealous of Nero’s artistic accomplishments and his visionary plans for a newer, more modern Rome. He had already instituted a strict building code, and in spite of the severe criticism levied against him for his engineering ideas, the Corinth Canal, built after his death, followed his original design.

Did Nero, in an attempt to shed guilt for the fire, place the blame on the convenient scapegoats, the Christians? Dando-Collins suggests otherwise. The Christian population in Rome at the time of the great fire was not very large, he notes, and Egyptian followers of Isis were summarily executed as well. Dando-Collins maintains that Nero was not the insane, sadistic leader that many historians have portrayed him to be. Instead, says the author, he was “incredibly tolerant of those who lampooned him,” and often stayed the executions of many prisoners that he could have had put to death.

Dando-Collin’s account of Nero’s brief life, the conspiracy that was concocted against him, and the great fire that consumed 70 percent of the Eternal City is intriguing. Whatever the truth of the matter, Rome would never be the same after the disastrous inferno. It would not only change the landscape of Rome, but alter its history as well. Nero, faced with arrest and assassination, committed suicide four years later. “While many future emperors would include ‘Caesar’ in their name,” writes Dando-Collins, “Nero was the last of the Caesar dynasty, a situation that many Romans lamented.”

Civil War Arkansas 1863: The Battle for a State by Mark K. Christ, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2010, 321 pp., notes, index, maps, photos, $34.95, hardcover.

Civil War Arkansas 1863: The Battle for a State by Mark K. Christ, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2010, 321 pp., notes, index, maps, photos, $34.95, hardcover.

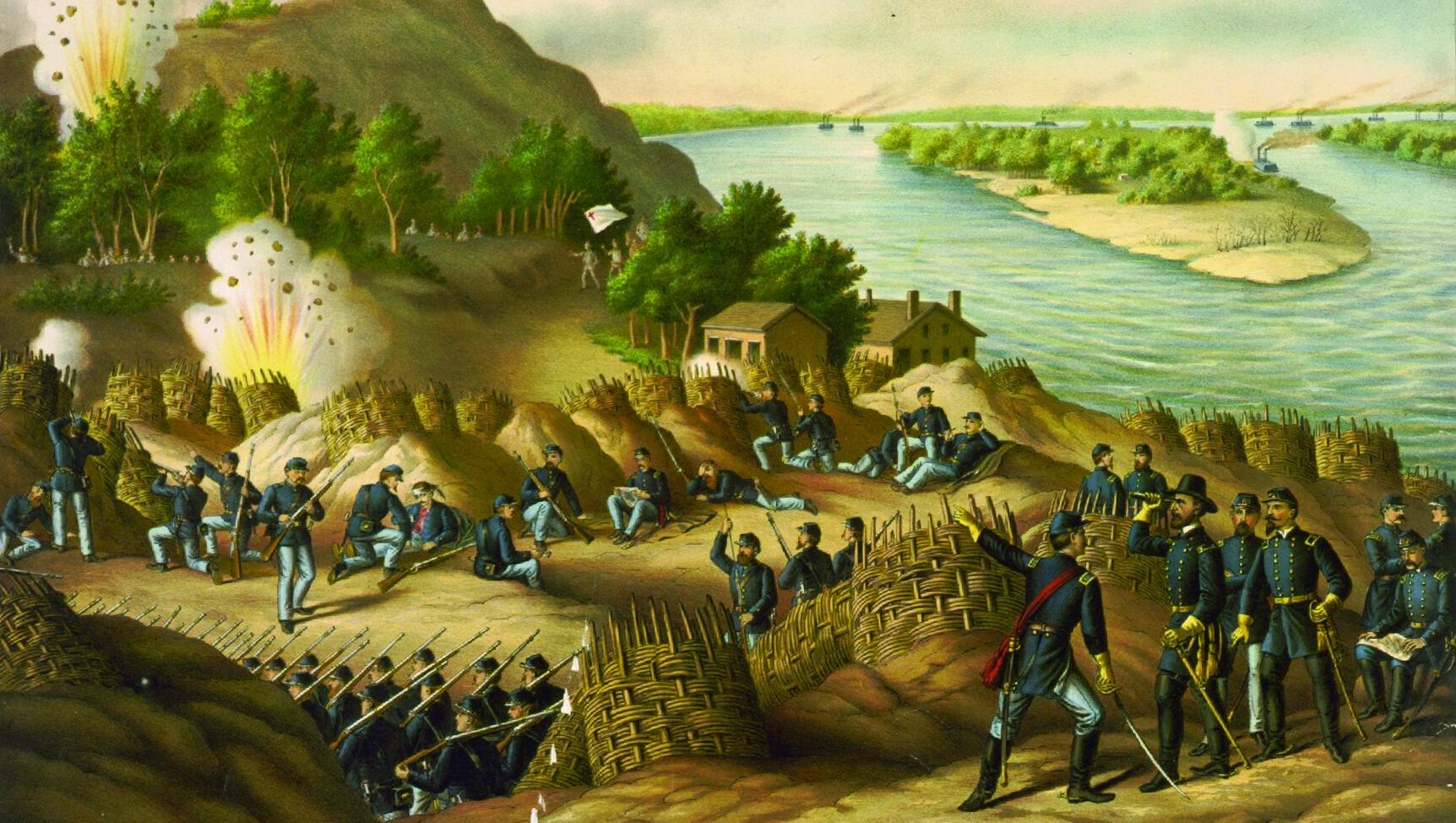

The State of Arkansas was a much-sought-after prize as the year 1863 dawned. Although Union forces were threatening Vicksburg, The Army of Northern Virginia was racking up impressive victories against the Union forces in the eastern theater. Confederate troops occupied the majority of Arkansas and the adjacent Indian Territory at the beginning of the year.

The stage was set for a decisive struggle to determine which side would control the fertile Arkansas River Valley. The rich agricultural land yielded a wide variety of crops and, as one Texan wrote, the “valleys of the Arkansas and White Rivers are the great granaries of the state and the seat of its greater wealth.”

In September 1863, the drive to seize the strategically important region began in earnest. Union Brig. Gen. John W. Davidson’s cavalry moved on Little Rock in early September. As the horsemen crossed the Arkansas River and raced toward the city, they encountered Confederate soldiers at Bayou Fourche. Davidson employed his artillery well, and soon the retreating Rebels were streaming toward Little Rock with the news that the Yankee cavalry was coming.

Instead of defending the city, Confederate commander Maj. Gen. Sterling Price ordered his men to withdraw, declaring that “the Yankees were not going to entrap him like they did Pemberton at Vicksburg.” By late that afternoon, Price’s army had made good its retreat. “The men grumbled and protested at giving up the town,” wrote Silas Turnbo, a soldier in the 27th Arkansas Infantry. “It was our last hope for Arkansas and it would soon be in the hands of the Federals.”

Turnbo’s prophetic words would ultimately prove to be correct. As the 3rd Minnesota Infantry triumphantly marched into Little Rock later that day, their music drove the final nail into any Confederate hopes of remaining in the state. The Federals now had firm control of the lush, crop-producing valley.

What had started as a bleak year for the Union had been transformed into an extremely productive one. Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant finally took Vicksburg in July, and another Union army repelled Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania at Gettysburg. The Mississippi River was under the control of Union gunboats, and now Arkansas had fallen. Although there were still 18 more months of bloody civil war, the year 1863 signaled the beginning of the end of the Confederacy.

The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape by Alexander Mikaberidze, Pen & Sword, South Yorkshire, England, 2010, 284 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, $31.00, hardcover.

The Battle of the Berezina: Napoleon’s Great Escape by Alexander Mikaberidze, Pen & Sword, South Yorkshire, England, 2010, 284 pp., maps, illustrations, notes, $31.00, hardcover.

When his ill-fated invasion of Russia turned sour, French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte escaped through the frozen Russian countryside. However, when his Grande Armee reached the raging Berezina River on November 26, 1812, a feeling of impending doom swirled through the ranks. The waterway, normally frozen solid by that time, was not. An unseasonable warming trend had kept the river from freezing and, to make matters even worse, the Russian Army had converged on the French and was determined to destroy them.

With the Russians having destroyed the ridges, French engineers went to work erecting a makeshift one. Napoleon tricked the Russians into thinking that his army was moving to the south, and when they took the bait, he quickly began his crossing.

Many of the camp followers did not cross when told to do so. However, when General Jean Elbe ordered the bridge burned, they panicked and attempted to cross. Thousands died in the ensuing melee, either being burned, crushed to death, or murdered by the rampaging Cossacks. Nevertheless, the bulk of Napoleon’s forces somehow made it across.

The author gives much of the credit for the operation to the Little Corporal’s subordinates: Elbe and Marshals Michel Ney and Claude Victor-Perrin. Still, the fiasco cost the French dearly. Some 25,000 soldiers were lost, and what remained of the Grande Armee was a mere skeleton. Like the English at Dunkirk, the name Berezina is synonymous among Frenchmen with catastrophic defeat.

Noble Warrior: The Story of Maj. Gen. James E. Livingston, USMC (Ret.), Medal of Honor by James E. Livingston, Colin D. Heaton, and Anne-Marie Lewis, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 247 pp., notes, maps, photos, $28.00, hardcover.

Noble Warrior: The Story of Maj. Gen. James E. Livingston, USMC (Ret.), Medal of Honor by James E. Livingston, Colin D. Heaton, and Anne-Marie Lewis, Zenith Press, Minneapolis, MN, 2010, 247 pp., notes, maps, photos, $28.00, hardcover.

For 30 years, Maj. Gen. James Livingston enjoyed a stellar career as a Marine officer. As a company commander with the 2nd Battalion, 4th Marines in Vietnam, he received the Medal of Honor. The horrific three-day struggle at Dai Do in northern Vietnam in 1968, sometimes referred to as the Battle of Dong Ha, was a bloody encounter that pitted hundreds of North Vietnamese Army soldiers against the understrength Marine forces scattered across the region in small firebases that defended the area. From April 30 to May 3, the “Magnificent Bastards” of the battalion held off a large enemy contingent that was attempting to attack the huge Marine supply base at Dong Ha.

What makes Livingston’s book a real treat to read is his personal reflections about the role of the media, the military today, and the fighting that is raging in the Middle East. He staunchly believes in a free press, but in his opinion, there should be a time delay before a reporter’s story is released to the public. “Our enemies watch TV as well,” he wrote, “and do not think that because they may not have running water that they are stupid.”

Livingston also explains his viewpoint on the world’s trouble spots—North Korea, Iran, the Balkans, and China—and the critical burden the president and Congress must face. Despite this, Livingston has his doubts on the outcome. His fear is that the politicians will continue to do business as usual in Washington and forget the American people, and why they were elected in the first place.

“Perhaps there should be a boot camp for politicians, as in the Corps, where the individuality of a person is stripped away, and they are molded mentally into a team mentality, an esprit de corps, where there is a greater purpose than that of the individual,” he writes. “Politicians can learn a lot from Marines.”

I Am Heartily Ashamed, Volume II: The Revolutionary War’s Final Campaign as Waged from Canada in 1782 by Gavin K. Watt, Dundurn Press, Toronto, Canada, 2010, 464 pp., notes, maps, illustrations, $30.00, softcover.

I Am Heartily Ashamed, Volume II: The Revolutionary War’s Final Campaign as Waged from Canada in 1782 by Gavin K. Watt, Dundurn Press, Toronto, Canada, 2010, 464 pp., notes, maps, illustrations, $30.00, softcover.

An overlooked aspect of the American Revolution is brought to life in this absorbing account of the bloody fighting that occurred along the northern frontier of the fledgling United States in the early 1780s. The lush, green Schoharie Valley, located west of Albany, was the scene of intense, bloody combat between Loyalist forces, their Indian allies, and Continental troops and local militias.

Always fearful of an American invasion after the aborted attempt at Montreal and Quebec, Maj. Gen. Frederick Haldimand, the governor-general of Canada, ordered that Fort Ontario be rebuilt in 1782. Upon learning of this, General George Washington dispatched Colonel Marinus Willett to attack the fort, fearing the British were attempting to use the fortification as a stepping-off point for another series of attacks in the Mohawk Valley.

Unfortunately, Willett’s Indian guide got lost and the assault party was spotted by a British work detail. The attack was called off. It was not until 13 years later that the British finally ceded Fort Ontario to the United States.

Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation by William F. Trimble, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 270 pp., notes, index, photos, $37.95, hardcover.

Hero of the Air: Glenn Curtiss and the Birth of Naval Aviation by William F. Trimble, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 270 pp., notes, index, photos, $37.95, hardcover.

For readers intrigued by the history of naval aviation, this biography of Glenn Curtiss, one of its pioneers, is a welcome addition. Along with the Wright brothers, Curtiss revolutionized the world of flight with his innovative designs, which catapulted the United States into the forefront of naval aviation.

Born in Hammondsport, New York, in 1878, Curtiss was fascinated with motors and engines. He soon was building and repairing bicycles, the rage at that time, and after the flight of the Wright brothers at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, he became captivated with the new flying machines.

He began his career with the Aerial Experiment Association in Nova Scotia, under the tutelage of Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone. His reputation as a designer and pilot soon brought him to the attention of the Wrights, and the trio formed their own company, the Curtiss-Wright Corporation. His long relationship with the U.S. Navy began in 1910, when a pilot successfully took off from a makeshift platform on the forward deck of the USS Birmingham and flew to shore. He relocated his headquarters to San Diego and began training pilots for the military in earnest.

It was through the tireless efforts of men like Glenn Curtis that the American military was transformed into a force to be reckoned with in aviation. His ground-breaking designs and dedication to his profession helped make aviation an essential arm of the U.S. Army and Navy and contributed greatly to the nation’s victories on the battlefield in ensuing years.

The Battle of Marathon by Peter Krentz, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2010, 256 pp., notes, maps, illustrations, $27.50, hardcover.

The Battle of Marathon by Peter Krentz, Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2010, 256 pp., notes, maps, illustrations, $27.50, hardcover.

Author Peter Krentz does a remarkable job of describing the ancient Battle of Marathon and why it is was so important to the Greeks and to world history. The Athenians met an Persian force led by King Darius I on the field of Marathon in 490 bc.

Prior to this engagement, the Athenians had fought more like a mob than as a well-trained army. However, under the leadership of Miltiades, they devised a plan that would allow them to approach the Persian force, known for their expert archers, with little or no casualties. They would simply run at them, full-tilt, and count on the element of surprise to carry the day. The Greeks raced forward for several hundred yards, even though their heavy armor weighed them down, then smashed into the bewildered Persians. In the end, the Greeks drove Darius’s men from the battlefield and seized seven of his warships in the process.

As the author suggests, Marathon was indeed a watershed battle, demonstrating to the world that the seemingly invincible Persian Army could be defeated.

The Wolf: How One German Raider Terrorized the Allies in the Most Epic Voyage of WWI by Richard Guilliatt and Peter Hohnen, Free Press, New York, 2010, 400 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.00, hardcover.

The Wolf: How One German Raider Terrorized the Allies in the Most Epic Voyage of WWI by Richard Guilliatt and Peter Hohnen, Free Press, New York, 2010, 400 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.00, hardcover.

Here is a little-known account of one of the most unusual stories to emerge from World War I. The German ship Wolf embarked on a 444-day, 64,000-mile voyage, ostensibly as a freighter. In reality, Wolf was a floating arsenal of torpedoes, mines, cannons, wireless receivers, a movie camera, and a seaplane, equipped to destroy British shipping. The one thing that made this instrument of terror vastly different from other ships of this nature was the German captain, Karl Nerger, who did everything in his power not to kill civilians. As a result, his vessel became a floating prison that eventually housed more than 400 men, women, and children.

In addition to the details of the remarkable trip that Wolf embarked on, the book includes incredible accounts of what transpired between the crew and the prisoners. One such individual, Gerald Haxton, the secret lover of English novelist W. Somerset Maugham, had a checkered past. Some believe he was a spy for the British. Also on board were the Camerons, an American couple whose daughter Juanita became the ship’s mascot, and Rose Flood, whose sexual escapades prompted another female detainee to refer to her as “a beast of the lowest.”

The fact that Wolf logged 64,000 miles on its incredible 15-month journey is astonishing in itself. It is almost unbelievable that she returned intact to her home port in Germany—a truly remarkable accomplishment.

After the War: The Lives and Images of Major Civil War Figures After the Shooting Stopped by David Hardin, Ivan R. Dee Publisher, Chicago, IL, 2010, 335 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.95, hardcover.

After the War: The Lives and Images of Major Civil War Figures After the Shooting Stopped by David Hardin, Ivan R. Dee Publisher, Chicago, IL, 2010, 335 pp., notes, index, photos, $27.95, hardcover.

What becomes of celebrated generals after a war is often more interesting than what they did in the conflict. David Hardin’s new book delves into the escapades of some of the Civil War’s more prominent individuals. Included are people like Ulysses S. Grant, who became president, only to be disgraced by a scandal-ridden administration. He also describes the postwar careers of Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest, who became involved with the notorious Ku Klux Klan, and the arrogant and egotistical George Armstrong Custer, who met his fate, along with 225 of his troopers, at the Battle of the Little Big Horn in June 1876.

One person in the book whose story is particularly enlightening is Mary Boykin Chesnut. The South Carolina native kept a journal during the war and made many observations that historians continue to use as a window into the past, to obtain a better understanding of what occurred during that tragic period of American history. As Hardin points out, Chesnut’s “poignant book is the closest to an audio of the Civil War as can be found.”

Benjamin Franklin and the American Revolution by Jonathan R. Dull, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, 2010, 184 pp., notes, $14.95, hardcover.

Benjamin Franklin and the American Revolution by Jonathan R. Dull, University of Nebraska, Lincoln, 2010, 184 pp., notes, $14.95, hardcover.

Historian Jonathan Dull’s new book provides insight into one of our most enthralling founding fathers, Benjamin Franklin, who, with the possible exception of George Washington, was the important cog in the framework of the American Revolution.

For more than 30 years, Dull read Franklin’s letters and edited 20 volumes of the Pennsylvania native’s personal papers. The majority of Americans envision Franklin as a genial man, a great inventor and all-around wise man with a keen eye for the opposite sex. However, the author’s research uncovers a more complex individual, one who harbored an intense hatred of King George III and the Tories who supported him, including Franklin’s own son.

Franklin spent nine years in France cultivating a special relationship between the two countries that would immeasurably aid the Colonies in gaining their independence from Great Britain. Upon his return to the United States, he spent months as a member of the Continental Congress working to adopt a constitution. He was an advocate of the abolishment of slavery and, until his dying day, remained an ardent revolutionary.

The Gun: The AK-47 and the Evolution of War by C.J. Chivers, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2010, 496 pp., notes, photos, $28.00, hardcover.

The Gun: The AK-47 and the Evolution of War by C.J. Chivers, Simon & Schuster, New York, 2010, 496 pp., notes, photos, $28.00, hardcover.

Its official name is the Avtomat Kalashnikova, meaning “the automatic by Kalashnikov,” a senior sergeant in the Russian tank corps who had designed it. The number 47 is taken from the year 1947, when the weapon was first designed. And there you have it, the AK-47—arguably the most prolific rifle in the world.

The stubby-looking firearm, with its distinctive sound, remains a favorite among armies and terrorist groups. Although cheaply manufactured, it rarely jams, a feature that most soldiers prefer on the battlefield—ask anyone who had to use the early model of the M-16 in Vietnam, when such dangerous malfunctions were prevalent.

The author, a former U.S. Marine combat infantry officer, does a good job in tracing the beginnings of the AK-47 and its meteoric spread to become the rifle of choice for many armies throughout the world. Although the author notes that the AK-47 will at some point be replaced by another inexpensive but reliable firearm, its deadly history will remain with us forever.

Beneath the Waves: The Life and Navy of Capt. Edward L. Beach, Jr. by Edward F. Finch, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 262 pp., notes, index, photos, #34.95, hardcover.

Beneath the Waves: The Life and Navy of Capt. Edward L. Beach, Jr. by Edward F. Finch, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2010, 262 pp., notes, index, photos, #34.95, hardcover.

Here is a wonderful addition to any reader’s personal library about one of the great pioneers of the U.S. Navy’s submarine service: Edward L. Beach, Jr. Beach graduated second in his class at the United States Naval Academy in 1939 and went on to have a distinguished career during World War II. He took part in the Battle of Midway and participated in a dozen combat patrols, being awarded the Navy Cross, the Silver Star, and the Bronze Star with “V” device.

Beach also enjoyed remarkable success as an author. He drew upon his submarine experience to write his celebrated novel Run Silent, Run Deep, which was later made into a successful Hollywood movie. He received numerous literary awards and accolades before his death in December 2002 at the age of 84.

Finch’s account is a glowing tribute to a man who contributed much to America’s naval service—and to the literary world—helping people gain a better insight into how the U.S. Navy really operates.

A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution by Theodore P. Savas and J. David Dameron, Savas Beatie, New York, 2010, 360 pp., index, maps, $19.95, softcover.

A Guide to the Battles of the American Revolution by Theodore P. Savas and J. David Dameron, Savas Beatie, New York, 2010, 360 pp., index, maps, $19.95, softcover.

As the authors note in the beginning of the book, the American Revolution is enjoying a resurgence of popularity. Reflecting that resurgence, the authors here have gone into great detail about the battles, both major and little-known skirmishes, the units, and the leaders on both sides of the conflict.

Each battle is accompanied by a map, a list of casualties, the outcome, and how it impacted the Revolution. A list of further readings is also given, so that anyone interested in learning more about any particular battle can do so.

In addition, there is a list of all Continental ships, as well as British and American units that took part in the fighting, French and Spanish military that contributed to the American side, and every Continental Army unit that was present at Yorktown when Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered. The book will prove an indispensable guide for those visiting the battle sites of the American Revolution.

Mississippi in the Civil War: The Home Front by Timothy B. Smith, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2010, 260 pp., index, notes, photos, $40.00, hardcover.

Mississippi in the Civil War: The Home Front by Timothy B. Smith, University of Mississippi Press, Jackson, 2010, 260 pp., index, notes, photos, $40.00, hardcover.

Many historians concentrate their efforts on a particular battle or campaign, but usually overlook another important aspect of any war—the home front, and how residents cope with war. Nowhere is this more evident than in the Civil War. Many southerners had to endure food shortages, inflation, and the loss of family members, while the bloody struggle dragged on for four long years.

Mississippi was one southern state that suffered greatly during the war. The invading Union forces seized the capital of Jackson, dismantled the political infrastructure, burned and looted throughout the state, and laid siege to Vicksburg, which devastated the civilian population there.

“Mississippi was crushed in its bid for independence and suffered the consequences of the attempt,” the author writes. “But the affliction did not end there; the state’s problems did not cease when the surrender documents were signed. Mississippi faced an unknown future in which the state would suffer the consequences of war far into the future, in some cases even to the present day.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments