By David Lippman

The ferocious battle for the island of Saipan in the Marianas was won by U.S. Marines and U.S. Army troops that defeated the Japanese during 39 days of heavy fighting from June 15 through July 9, 1944.

The death struggle for Saipan was followed by another ferocious battle between the Army and the Marine Corps when the top Marine general on the island, Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith, relieved the top Army general, Maj. Gen. Ralph Smith, of his job as commanding officer of the 27th Infantry Division. Holland Smith fired Ralph Smith in the middle of the fighting. The abrupt dismissal set off fireworks at flag rank and in the media while generating a controversy that persists to this day.

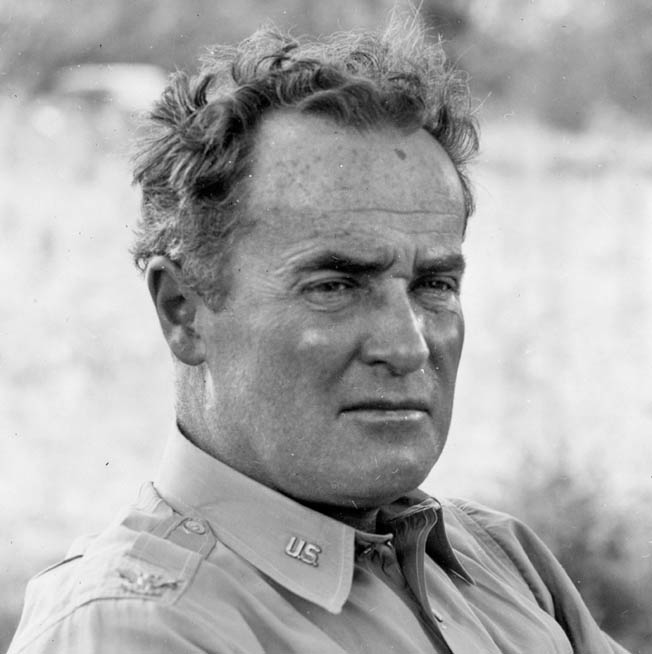

Ralph Smith: A Gentle Man and a Gentleman

At the center of the dispute was Ralph Smith, who led the 27th Infantry, a New York National Guard outfit, with many of its men drawn from the state’s farming and mountain country along with others from New York City’s tough neighborhoods. Ironically, Ralph Smith was not a New Yorker. He was born in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1893, and attended Colorado State College. He enlisted in the Colorado National Guard in 1916, was commissioned second lieutenant, and was promoted straightaway to first lieutenant. Taught to fly by Orville Wright, Ralph Smith gained the 13th pilot’s license in the history of the United States, signed by Wright himself.

Ralph Smith graduated from Officers Training School at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, in 1917, and served on the Mexican border with the 35th Infantry Regiment. He was sent to France with the 16th Infantry Regiment, part of the 1st Brigade, 4th Infantry Division. He saw a lot of action, including the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, earning a Purple Heart and a Silver Star with Oak Leaf Cluster.

On returning home, Ralph Smith served in the usual peacetime Army roles including adjutant of the 2nd Infantry Brigade in Kentucky, French instructor at West Point, training and instructing at the Infantry School, and attending the Command and General Staff School at Fort Leavenworth in 1927-1928. Next up was a tour at the Presidio in San Francisco, then a return to the Command and General Staff School as an instructor. He graduated from the U.S. Army War College in 1935, and was then chosen to study at the prestigious École de Guerre in France.

In 1937, Ralph Smith returned to the United States. He was promoted to colonel in 1938, serving as Chief of the Operations Branch, Military Intelligence Division of the War Department General Staff. By 1940, he was Chief of the Plans and Training Branch of the G-2 Division. The following year, Ralph Smith received his brigadier general’s star. All who knew him regarded Ralph Smith as gentle man and a gentleman.

In early 1942, the 27th Infantry Division was moved from New York to Hawaii to defend the islands against Japanese attack. The 27th had a proud tradition—one of its units was the 165th Infantry Regiment, which in its World War I incarnation had been the legendary “Fighting 69th” Infantry Regiment commanded by “Wild Bill” Donovan in the Argonne. Ralph Smith was given command of this division.

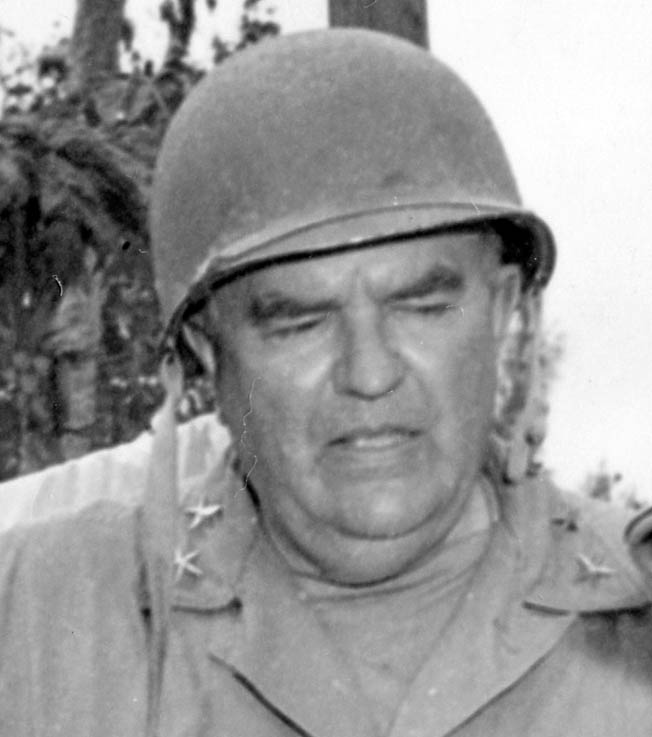

Holland “Howlin’ Mad” Smith

Ralph Smith’s chief antagonist was a ferocious Alabaman, born in 1882. Holland McTyeire “Howlin’ Mad” Smith was the son of a prominent Alabama politician. While attending the Alabama Polytechnic Institute, a military school in Auburn, Holland Smith read about Napoleon and decided to become a career officer. He graduated from the Alabama Polytechnic Institute and then went to law school at the University of Alabama, where he was a better sprinter than scholar but still gained a law degree and was admitted to the bar.

When Holland Smith sought an Army commission, he went to Washington to plead his case to his congressman, but the Army turned him down. Some historians suggest that may have given him a lifelong dislike of the Army. A congressman then suggested Holland Smith try his luck with the Marines.

“What are the Marines?” Holland Smith asked in all candor, and he found out on March 29, 1905, when he was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Corps. He was soon nicknamed “Howlin’ Mad,” a play on his name and initials, and went to France with the 8th Marine Regiment in 1917. He earned a Croix de Guerre with Palm in combat. Between the wars, he became one of the Marines’ pioneers of amphibious warfare.

In March 1937, Colonel Holland Smith became director of operations and training at Marine Headquarters in Washington, D.C. In September 1939, he gained general’s stars and command of the 1st Marine Brigade. This was doubled in size under his leadership and became the 1st Marine Division. In June 1941, Holland Smith took command of the Amphibious Force, Atlantic Fleet.

A short, heavy-set man with a moustache, round, thin glasses, a hard face, and cigar, Holland Smith resembled an elderly business tycoon, not a poster general. Aged 60, his appearance and girth troubled a medical board, which found him physically unfit for combat service due to a diagnosis of severe diabetes. The diagnosis proved to be a mistake, and Holland Smith headed to the West Coast to lead amphibious training as the Marines prepared for Guadalcanal.

There, Holland Smith trained Leathernecks for their impending ordeal and Army troops for the Aleutian campaign. While his duties were vital, Smith, like most line officers, fretted about not getting into combat and beseeched Admiral Chester Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific Fleet, for a battle role. Nimitz gave Holland Smith the post of Commanding General, Fleet Marine Force Pacific, and Holland Smith took up his duties on September 5, 1943.

First Conflict on Makin

Holland Smith headed the invasion of Tarawa in the Gilberts and its nearby islands of Makin and Abemama in November 1943, and under his command was Ralph Smith’s 27th Infantry Division. The two Smiths first clashed during the assault on Makin.

On November 20, the 27th Division’s 165th Infantry Regiment, under Colonel Gardiner Conroy, assaulted Makin and faced fierce defenders. On D+2, Holland Smith went ashore to check on the battle. He found the corpse of Colonel Conroy lying in an open area. Conroy, walking erect on the beach on D-day, had been shot between the eyes by a Japanese sniper, and the body had not been retrieved.

Holland Smith was angered that the colonel’s body had lain for two days “in full sight of hundreds of men,” a detriment to morale. Worse, when Conroy had been killed the Army troops had withdrawn tanks, mortars, and machine guns without firing a shot. The 27th Division’s apparent lack of aggressiveness, poor training, and weak discipline irritated the fierce Holland Smith. He later wrote, “Had Ralph Smith been a Marine I would have relieved him on the spot.” He also called the 27th’s capture of the island “infuriatingly slow.”

Meanwhile, the Marine landings on Tarawa were more successful despite suffering heavy casualties, burnishing the tactics and reputation of the Leathernecks and their tough-talking commander.

The Smiths were united again for an amphibious assault on Eniwetok in February 1944, and once again Holland Smith was unhappy with Ralph Smith’s performance.

The Benning Method vs Marine Aggressiveness

On March 15, 1944, Holland Smith became the Marine Corps’s second three-star general with command of the V Amphibious Corps. With great reluctance, he accepted the 27th Infantry into his command for the invasion of Saipan.

When the 27th Infantry came ashore on Saipan, the actual landing was close to farce. The GIs landed by night, their landing craft moving through waters jammed with Navy vessels. Holland Smith’s corps staff did not tell the Navy that the Army was coming ashore.

Communications broke down, and Navy officers yelled through loud-hailers at the Army officers demanding to know who these people were and where they were going while point machine guns at them. The infantry officers had to wheedle and beg to get their men ashore. Once aground, the men of the 165th Infantry Regiment were exhausted and seasick before they even met the Japanese. The 105th Infantry Regiment lacked its vehicles, rations, and ammunition.

But Ralph Smith did his best, getting the 27th off the beach and into battle, headed for Mount Topotchau. A former Fort Benning infantry instructor, Ralph Smith used the tried-and-true Benning methods to approach the mountain: probe until enemy strongpoints were unmasked, hit them with accurate artillery fire, and use patrols to find ways to outflank the main positions. Frontal assaults up valleys were only acceptable in an emergency.

Ralph Smith’s methodical probing irritated Holland Smith, who favored the aggressive violence and direct action that was the Marine hallmark. Personalities as well as tactical methods were now clashing on the rocky island. The Army made little progress.

Ralph Smith Relieved of Duty

On June 24, after consulting with his superiors, Vice Admiral Richmond Kelly Turner and Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance, Holland Smith relieved Ralph Smith, sending a captain from the Adjutant General’s Corps with the official order, typed up on V Amphibious Corps stationery, and the additional proviso that Ralph Smith and a single aide must leave Saipan by dawn on the 25th. Maj. Gen. Sanderford Jarman, who was to command the Army base on Saipan once the island was secure, would take over the 27th Infantry Division.

Ralph Smith offered to stay to help with the transition, but that offer was refused. At 5:17 am on June 25, Ralph Smith and his aide boarded a Navy patrol plane and started winging back to Eniwetok, a 10-hour flight, ultimately headed for Hawaii.

Holland Smith later wrote, “Relieving Ralph Smith was one of the most disagreeable tasks I have ever been forced to perform,” adding that he personally liked the man and considered him “professionally knowledgeable.”

But at the time, Holland Smith told Time magazine war correspondent and future Marine historian Robert Sherrod, “Ralph Smith’s my friend, but good God, I’ve got a duty to my country. I’ve lost 7,000 Marines. Can I afford to lose back what they have gained? To let my Marines die in vain? I know I’m sticking my neck out—the National Guard will try to chop it off—but my conscience is clear. I did my duty. When Ralph Smith issued an order to hold after I told him to attack, I had no other choice than to relieve him.”

A Board Examines Ralph Smith’s Relief

Holland Smith was right about the oncoming storm. When Ralph Smith arrived in Hawaii, he reported to Lt. Gen. Robert C. Richardson, the senior Army commander in the Pacific, and Richardson was outraged. He told Ralph Smith to take as much time as necessary to prepare a report on everything that had happened on Saipan. On July 11, Ralph Smith produced a 34-page document with annexes and copies of his communications with Holland Smith. A copy went to Nimitz.

Ralph Smith urged Richardson, “No Army combat troops should ever again be permitted to serve under the command of Marine Lieutenant General Holland M. Smith.”

While Ralph Smith and his officers typed up their report, the ranking Army officers on Saipan vented their considerable displeasure over the relief and Holland Smith’s command to Richardson as well. Maj. Gen. George W. Griner, who took over the 27th Infantry Division from Jarman on June 26, told Richardson how he had quarreled so bitterly with Holland Smith that he came away from Saipan with the “firm conviction that [Holland Smith] is so prejudiced against the Army that no Army Division under his command alongside of Marine Divisions can expect that their deeds will receive fair and honest evaluation.”

Meanwhile, Richardson ordered Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, son of a Confederate Civil War hero and victor of the Aleutian Campaign, to head a five-general board to examine the circumstances of Ralph Smith’s relief.

While the gravelly Buckner and his board studied the files, Richardson flew to Saipan in his capacity as commander of all U.S. Army forces in the Pacific Ocean Areas. First he bucked up the 27th Division’s morale by staging a review and presenting decorations for valor—without the knowledge or consent of Holland Smith, who was angry at this breach of military etiquette and infringement on his authority as Corps commander.

Next, Richardson berated Holland Smith, barking, “I want you to know that you cannot push the Army around the way you have been doing; you and your Corps commanders aren’t as well qualified to lead large bodies of troops as general officers in the Army, yet you dare to remove one of my generals. You Marines are nothing but a bunch of beach runners anyway. What do you know about land warfare?”

Faced with this verbal barrage, the normally volatile Holland Smith held his temper, but after the conversation he stormed off to Turner’s flagship and vented his frustration.

Turner did the next round of exploding, questioning Richardson’s right to exercise any command functions in the battle area and even to visit Saipan. Richardson coolly said that he had permission from Nimitz to visit Saipan, and Turner angrily demanded the proof. Richardson went over Turner’s head to Spruance, who gave Richardson a “what do you expect from Turner” shrug.

Spruance and Turner complained to Nimitz about Richardson’s visit and verbal attack on Holland Smith.

Conclusions of the Board

The Buckner Board reviewed the increasingly ugly mess, and arrived at four conclusions:

(1) Holland Smith had full authority to relieve Ralph Smith.

(2) The orders effecting the change of command were properly issued.

(3) Holland Smith “was not fully informed regarding conditions in the zone of the 27th Infantry Division” when he asked for Ralph Smith’s relief.

(4) The relief of Ralph Smith “was not justified by the facts.”

The board faulted the V Amphibious Corps command for not realizing that the 27th Division was facing much tougher opposition than the Corps anticipated, and the division’s lack of aggressiveness was due to Japanese defenses, not sluggish Army leadership. The Buckner Board noted that the Marine Corps headquarters team and staff work were enormously sloppy and asserted that the senior Marine leadership had not been anywhere near the 27th Division’s sector and simply did not know what the Army had been up against on Mount Tapotchau.

The Army had a point. Saipan was the first time in its 150-year history that the U.S. Marine Corps had fought a corps-level action, and while the Leathernecks were fierce fighters and professional warriors they simply lacked the experience needed at that level of combat operations.

The Navy and Marine Corps reacted with predictable irritation. Holland Smith wrote to Nimitz that the Buckner Board’s conclusions were unwarranted, adding, “I was and am convinced that the 27th Division was not accomplishing even the combat results to be expected from an organization which had had adequate opportunity for training.”

Turner chimed in, resenting the board’s implied criticism in “pressing Lt. Gen. Holland M. Smith … to expedite the conquest of Saipan so as to free the fleet for another operation.” He added that Holland Smith’s relief order was not “based on either personal or service prejudice or jealousy.”

Richardson added his own harsh words in his report to Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, writing, “I feel it is my duty to make of record my urgent and considered recommendation that no Army combat troops ever again be permitted to serve under the command of Marine Lieutenant General Holland Smith. So far as the employment of Army troops are concerned, he is prejudiced, petty, and unstable. He has demonstrated an apparent lack of understanding of the acceptance of Army doctrines for the tactical employment of larger units.”

Jarman agreed, saying, “It is my earnest recommendation that in future operations of any kind where the Army and the Marine Corps are employed that under no circumstances should any Army divisions be incorporated into the Marine Corps. Their basic concepts of combat are far removed from that of the Army.”

Repairing the Rift Between the Services

The Buckner Board findings went next to Washington for review by Marshall and his Assistant Chief of Staff, Maj. Gen. Thomas T. Handy. They believed that while Holland Smith had some cause to complain about the 27th Division’s lack of aggressiveness, “Holland Smith’s fitness for this command is open to question” because of his deep-seated prejudice against the Army and that “bad blood had developed between the Marines and the Army on Saipan” to such a degree that it endangered future operations in the theater.

Handy advised that the two Smiths be ordered out of the Pacific but added, “While I do not believe we should make definite recommendation to the Navy for the relief of Holland Smith, I think that positive action should be taken to get Ralph Smith out of the area. His presence undoubtedly tends to aggravate a bad situation between the Services.”

The Deputy Chief of Staff, Lt. Gen. Joseph T. McNarney, examined the Buckner Board report and concluded that Holland Smith’s V Amphibious Corps staff work was below acceptable standards; there was reasonably good tactical direction on the part of Ralph Smith, but the division had poor leadership among its regimental and battalion commanders, a hesitance to bypass snipers “with a tendency to alibi because of lack of reserves to mop up,” poor march discipline, and lack of reconnaissance.

On November 22, 1944, Marshall gave his views to the Navy’s top seadog, Admiral Ernest J. King, expressing concern that “relationships between the Marines and the Army forces on Saipan had deteriorated beyond mere healthy rivalry.”

Marshall urged that he and King send identical telegrams to Richardson and Nimitz to “take suitable steps to promptly eradicate any tendency toward … disharmony among the components of our forces.” He also suggested another investigation into the Saipan affair to prevent its recurrence.

King wrote back to say that the Buckner Board findings were unilateral and suspect, contained intemperate attacks on the personal character and professional competence of Holland Smith, and he could not concur in any further investigations in which Richardson was a party because that officer had done enough damage by his “investigational activities during his visit to Saipan” and by convening the Buckner Board. That ended any further official action on the controversy.

William Randolph Hearst Brings Public Attention to the Feud

Unfortunately, now the controversy moved into the public arena. The Saipan battle was huge news in the United States, particularly the ghastly Japanese mass suicides on Marpi Point, which had been well-documented by film, photograph, and reporter accounts. The American public was shocked by how the island’s Japanese civilians chose suicide over surrender and the heavy U.S. casualty toll. The command controversy was raw meat for American press barons.

William Randolph Hearst’s empire opened the ink barrage. The aging reactionary titan was a major public supporter of the flamboyant and dramatic General Douglas MacArthur, who commanded the Southwest Pacific Theater. Hearst took advantage of Saipan’s high casualty lists and Ralph Smith’s firing to denounce the Navy, Marine Corps, and their leadership.

In his flagship newspaper, the San Francisco Examiner, Hearst editorialized that Army commanders used subtle, intelligent tactics while the Marines were one dimensional. “Allegedly excessive loss of life attributed to Marine Corps impetuosity of attack has brought a break between Marine and Army commanders in the Pacific,” Hearst wrote.

In another one of his major papers, the New York Journal-American, Hearst wrote, “Americans are shocked at the casualties on Saipan following already heavy losses by Marine commanders on Tarawa and Kwajalein.” Hearst accused Holland Smith of firing his Army subordinate when Ralph Smith protested “reckless and needless waste of American lives.”

Hearst had a simple solution to the controversy. Put Douglas MacArthur in supreme command of the entire Pacific Theater from the Aleutians to New Guinea. Putting MacArthur in command of everything was Hearst’s answer to most controversies—in 1948 and 1952 he would back the general for the presidency—but it fueled increasing debate.

The Feud Within the Press

The Navy had its partisans in the press war, however. Most notable of these was Charles Henry Luce, the publisher of Time and Life magazines. Luce’s admiration dated back to his youth as the child of American missionaries in China at the beginning of the 20th century. There, the Navy and Marines had burnished their reputation by protecting American commercial interests and citizens from the ravages of Chinese bandits, civil war, and later the Sino-Japanese conflict.

Luce also had a reporter assigned to Holland Smith. Robert Sherrod was close to the fiery Marine general and went ashore with the Marines on the first day of the Saipan invasion, staying with them through the entire grim battle. Sherrod wrote highly accurate stories about Leatherneck courage and enthusiasm. Certainly the Marines had fought well and victoriously, and they made good copy.

But Sherrod never visited the Army units, and he overplayed the Marines’ disgust at the 27th Division’s perceived failures. He wrote that while the Marines made great gains against tough Japanese resistance, entire Army battalions were pinned down for hours by a single Japanese gun position or sniper.

On September 18, 1944, Time magazine published an article by Sherrod supporting Holland Smith, which described the 27th Division as being commanded by an incompetent. Sherrod wrote that the 27th’s GIs “froze in their foxholes” and had to be rescued by the Leathernecks. Sherrod added, “When field commanders hesitate to remove subordinates for fear of interservice contention, battles and lives will be needlessly lost.”

Historian Geoffrey Perret wrote decades later that the humiliating article devastated the men of the 27th, and the division never recovered its toughness from the journalistic blow.

The debate raged on in the media and in public conversation, which annoyed Marshall, King, and General Henry “Hap” Arnold, head of the U.S. Army Air Forces, who were now wishing the entire affair would simply go away. They were more concerned with the next campaigns, in the Palau Islands, New Guinea, and the Philippines, than in refereeing the “War Between the Smiths.” It was time to end the whole affair.

Ralph Smith was given Maj. Gen. George Griner’s old command in Hawaii, the 98th Infantry Division, when Griner took over the 27th. This switch of division commanders was only temporary, though, as Marshall wanted the two Smiths separated for life.

Ralph Smith Transferred to the European Theater

Ultimately, Ralph Smith’s fluent knowledge of French saved his career. He was assigned as military attaché to General Charles de Gaulle’s Free French government, which had installed itself in Paris. Ralph Smith arrived just in time for the closing guns of the Battle of the Bulge and the opening guns of Operation Nordwind, Hitler’s offensive in Alsace against the U.S. Seventh and French First Armies. The two-pronged German drive was threatening to cut off Strasbourg, and the Americans wanted to withdraw from the city.

Unfortunately, Strasbourg’s possession was a major issue for de Gaulle. He was determined not to yield once more a city that had been annexed to Germany in 1870 to the Huns. General Dwight D. Eisenhower, Supreme Commander Allied Expeditionary Force, threatened to cut off supplies to de Gaulle’s troops if they did not withdraw. De Gaulle was obstinate. With the two Allies shouting at each other, quiet diplomacy was needed to resolve the situation, and Ralph Smith provided it. He convinced the French that American and French troops would fight to hold the city. Both Strasbourg and French honor were saved, a good deal of it through Ralph Smith’s efforts.

Holland Smith Sidelined

Holland Smith got a different reward. With six Marine divisions in the Pacific now, along with 28 artillery battalions, 12 Amtrac battalions, and four Marine air wings, the Marines now had an army rather than a corps in the field and needed a Marine headquarters to administer this force.

Holland Smith was named head of Fleet Marine Force, Pacific, which was a mixed blessing for the fiery warrior. While he oversaw the entire Marine war effort in the Pacific, he did not actually command Leathernecks in battle. Nor did he command Army troops again.

The invasion of Iwo Jima was purely a Navy-Marine show, and both services suffered heavy casualties while gaining the island and glory, but when the Marines were assigned for the invasions of Okinawa and Kyushu they came under Army command.

At Okinawa, the higher formation was the U.S. Tenth Army under General Buckner. Ironically, Buckner was killed late in the battle, and Marine Lt. Gen. Roy Geiger, who commanded the III Amphibious Corps, took temporary charge of the Tenth Army from June 18 to June 23 while General Joseph Stilwell flew in from the United States to assume command. Geiger thus became the only Marine officer to command a U.S. Army in the field.

In the planning for Operation Olympic, the invasion of Kyushu, and Operation Coronet, the invasion of Honshu, the Marines were to come under the U.S. Sixth Army and General Walter Krueger in Olympic and General Robert Eichelberger’s U.S. Eighth Army in Coronet. Both invasions were forestalled by the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, which hastened Japan’s surrender.

Continuing Controversy of the “War Between the Smiths”

But the controversy continued after the war, if not in the halls of high command, in the public eye. Holland Smith retired from the Marine Corps with his fourth star in May 1946, having served in the Corps for 41 years. He promptly wrote his memoirs, which were serialized in the Saturday Evening Post in 1948, and in book form in 1949 with the title Coral and Brass. In his memoirs, Holland Smith defended his decision to fire Ralph Smith and blasted the 27th Infantry Division for its perceived weaknesses.

The 27th Infantry Division’s official historian, Captain Edmund G. Love, wrote a rebuttal for the Saturday Evening Post as well, and another one for the division’s history, published by the Infantry Journal. Love defended Ralph Smith and his GI buddies.

The official Army and Marine Corps historians also weighed in on the controversy. The 1960 Army history, Campaign in the Marianas, by Philip A. Crowl, straddled the fence. Crowl said that Holland Smith’s orders were never clear, the division did fight hesitantly, and did not advance. Crowl concluded, “No matter what the extenuating circumstances were—and there are several—the conclusion seems inescapable that Holland Smith had reason to be disappointed with the performance of the 27th Infantry Division on the two days in question. Whether the action he took to remedy the situation was a wise one, however, was doubtful. Certainly the relief of Ralph Smith appears to have done nothing to speed the capture of Death Valley. Six more days of bitter fighting remained before that object was to be achieved.”

The Marine history was written in 1966 by Henry I. Shaw, Jr., Bernard C. Nalty, and Edwin T. Turndbladh and titled Central Pacific Drive.

The Leatherneck historians wrote: “The Smith against Smith controversy was caused by failure of the 27th Infantry Division to penetrate the defenses of Death Valley. Holland Smith had told the division commanding general that operations in the area had to be speeded up. Ralph Smith, who was thoroughly familiar with the tactical situation, informed Jarman of his own annoyance with the slow progress of his unit. He told the island commander that he intended to press the attack, but he postponed making the changes in command which, according to Jarman, he intimated might be necessary. The NTLF (Northern Troops and Landing Force) commander (Holland Smith), after stating that the objective had to be taken, saw that no significant progress had been made on 24 June and promptly replaced the officer responsible for the conduct of the Army division. The Army Smith offered his subordinates another chance, but the Marine Smith did immediately what he felt was necessary, without regard for the controversy he knew would follow.”

Ultimately, Ralph Smith probably had the last word. After retiring from the Corps, Holland Smith lived in La Jolla, California, pursuing his hobby of gardening until his death at age 84 in 1967. He is buried in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego.

Ralph Smith, however, became Chief of Mission for CARE (Cooperation for Assistance and Relief Everywhere) in France, retiring from the Army in 1948. After that, he was a fellow at the Hoover Institution on War, Revolution, and Peace, in California, and lived until 1998, dying at the age of 104. At his death, he was the oldest surviving general officer in the U.S. Army and had outlasted all of his critics.

A reasonable article with one noteworthy error. H. M. Smith’s memoir, “Brass and Coral,” assert that Colonel Gardner Conroy’s body lay for two days unattended after he was shot and killed. With excellent sources and citations, Harry A. Galley, in ” ‘Howlin’ Mad’ vs the Army,” (Presidio Press, 1986), lays this canard to rest. Among the witnesses was Col. James Roosevelt who was with Col. Conroy when he was killed. “To the best of my recollection Col. Conroy’s body was not only retrieved, but taken back to the beachhead.” (Letter from James Roosevelt to the author, 30 November, 1983.) “Father Lafayette Yarwood, the Catholic Chaplain on Makin, stated, ‘I know definitely that the burial [of Colonel Conroy] took place at 1500 hours on 21 June 1943. The statement of H. M. Smith is absolutely counter to the facts.” “Capt. Ernest Fleming reported, ‘Colonel Conroy’s body was moved from where it fell, by parties unknown to me, at about 0800, 21 June 1943…I personally viewed Colonel Conroy’s body at 0900 hours, 21 June 1943.’ ” Colonel Conroy was killed on D + 1 (21 June 1943) and recovered within a few hours.

I understand the Army-Marine divide as well as anyone but 65+ years later. All this is from 2003 so some things have changed for both services I’m sure.

My Army unit was with the 1st MARDIV during the Iraq invasion. The differences were pretty drastic above the battalion level I think. I’ll say this the Army unit that the MARDIV reminded me most of was the 82nd Abn.

The Army’s approach is a layered one with recon from USAF then helos, then light recon followed by heavier forces etc w/arty support while as near as we could tell the Marines generally seemed to us a ‘go that way until you clash with the enemy’ approach. I remember the 3rd ID liaison & I glancing at each other in w/WTF looks on our faces. At one point it really seemed that crazy but as the Brits who were with us on a different Army deployment said your ways are different but ‘it works for you’.

The Army seemed in 2003 to overplan while the Marines were guilty of the exact opposite.

The regular Army at least then knew mech warfare cold, far better than the Marines did. In an Army cav unit we used to immediately go into a lager, then dig foxholes in front of our vehicles if there longer than 20 min much less overnight. W/the Marines several times we’d literally pull over on the side of the road, not even in a herringbone formation, and spend the night which shocked us. I remember waking up and seeing civilians walking past us on the road.

The Marines I thought were strongest at the company level; belligerent, aggressive and so on. Absolutely not afraid of a fight at the rifle company level. If you wanted to play up close and personal they were ready.

One thing I noticed is the Marines were obsessed with talking about the Army while after 6 years on Ft Bragg I barely remember even speaking of them.

The National Guard is a whole other story, the less said the better.

Holland m. Smith was a crackpot at best, betio & Saipan is proof of that,, almost half of the invasion force mowed down at the start, r.ip. pfc Harvey Lee Levan U.S.M.C. 2nd Mardiv. June 15, 1944 Saipan

I agree with Betio- battle of Tarawa, the 8th marine regiment should have never been allowed to wade in on D+1, they got mowed down from Japs who had a clear line of fire, I’ve read various accounts on Tarawa and said there was a communication breakdown, that’s bull, someone should have gone out in person and personally told Gen Smith that red Beach 2 was not secure, my uncle Alexander Peña fought in that battle, 3rd battalion 6th marine regiment 2nd marine division, Guadalcanal, Tarawa, Saipan and Tinian, He was KIA July 30th 1944 on Tinian, those men who fought in those battles were heroes, all of them heroes, the greatest generation of all time.

My father served in the 165th Reg, 3rd Bat, H Company. He was S-2 on Makin, Saipan, and Okinawa; a projectionist in Hawaii and supply sergeant in Japan until his detachment on Nov. 15, 1945.

ly

He witnessed the death of the Colonel; as I recall, he thought he had witnessed the death of Col. Roosevelt. The death of the colonel was caused by an artillery round.

My father was responsible for the loading of a supply ship used for the assault of the 27th Div. while they were stationed in Hawaii. He was awarded the bronze star for his efforts, but always thought a medal such as that should only have been awarded for heroism.

On Saipan, he performed a couple of night patrols, and on one occasion, was ordered to report to Regimental hq, which declined as there were field phones at the intel command post; his persistence probably saved his life, the information was properly conveyed to regimental hq; and another squad leader in the 3rd Bat was killed that night when he walked back thru American soldiers to regimental hq.

He also took a squad out when ordered to ambush a battalion of Japanese soldiers at night; they set up noise makers, and got out of there. Any fool knows a squad doesn’t survive when assaulting a battalion of enemy soldiers.

The 165th was on the flank position of the 105th when it was hit by Japanese soldiers in a bonzai charge. The Japanese were pushing about 2,000 Korean slave laborers, who were unarmed, towards the 105th. The soldiers had to kill the Koreans to kill the Japanese. My father talked to members of the 105th after the action and saw a machine gun that warped due to the number and frequency of rounds during that segment of the battle.

On Okinawa, my father and his squad while Lt. Col. Claire was prepping his field officers for a night action to envelop a strongly held Japanese position inside catacombs and cross tunneling at Item Pocket. Orders came down from regimental command to make a frontal assault upon the position without artillery or tanks upon the position which has light motors, machine guns, and rifle men shooting thru rifle slips behind coral rock. The Colonel replied as to developing a night attack, and was relieved of command because he would not lie (he was a West Point officer). The unit made a feint and retreated, and took the position at night with satchel charges. It was at this point that a bullet when thru my dad’s sleve.

Excellent article, Dan Carlin mentioned the feud in his recent podcast. I wanted a bit more detail and found it here, thanks for research.

Well, wars war, you don’t win it by holding back, I,m with Holland Smith on this.

Well, it’s for sure only one side of the Smith vs Smith conflict is presented here, did it ever occur to anyone D-Day in Europe was 9 days before Saipan, and h.m. Smith had something to prove over the army

One fact only lightly noted here was that the Army and the Marines had traditionally different missions. The Pacific war had the effect of changing the missions of both as it was a different type of campaign from all previous wars. The overlap of missions, unfamiliarity with the other services’ tactics and even the political strains between them contributed to adverse effects on several missions and campaigns. The miracle is that the war proceeded as well as it did for the US and its allies in the Pacific. As I write this on Veterans Day, I marvel at the efforts of all concerned and the personal conflicts seem less consequential and so much more out of place.

All i know is the men & women of WW2 are the Greatest Generation !!

Contraversy be damned.

????