By David A. Norris

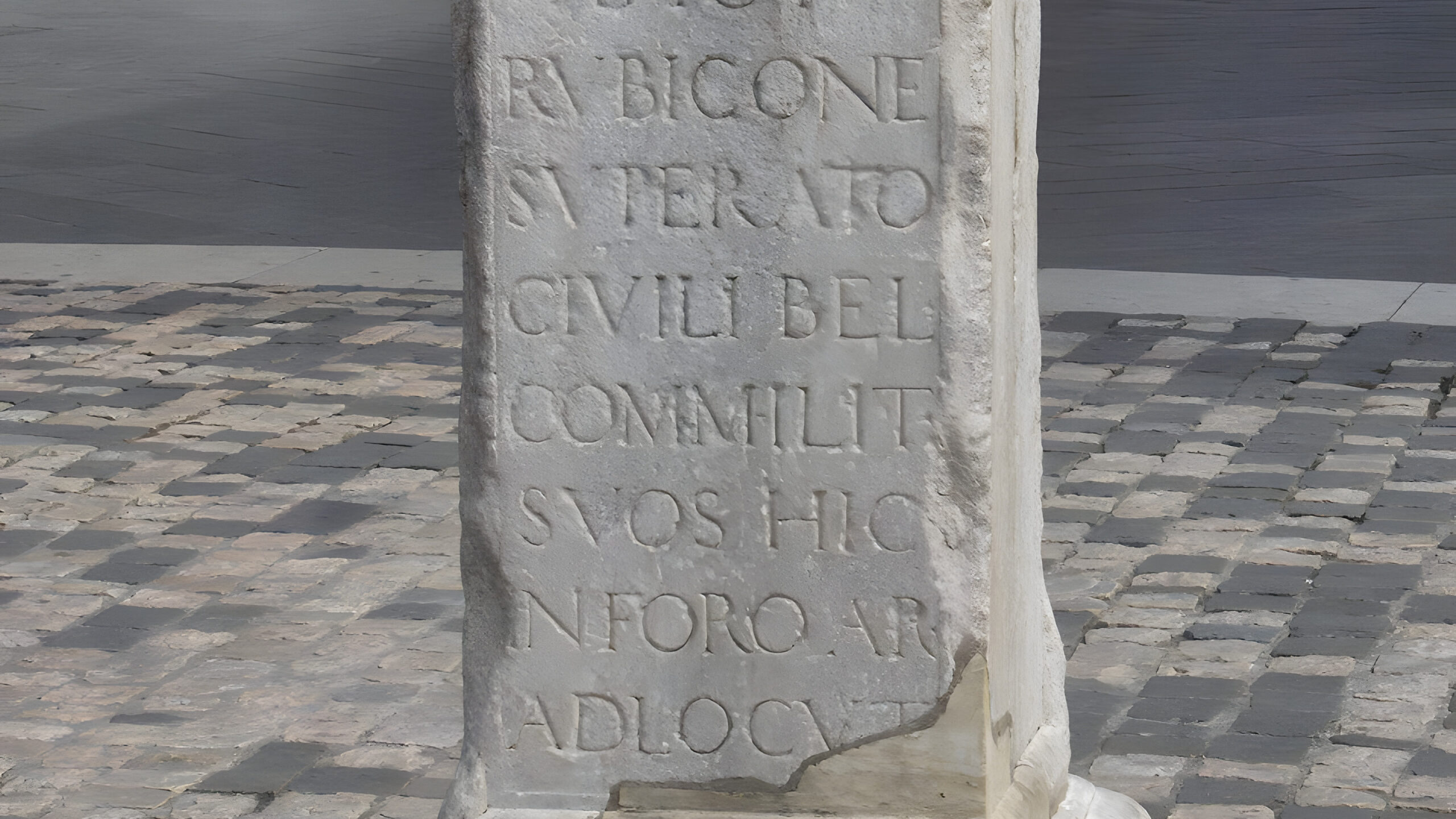

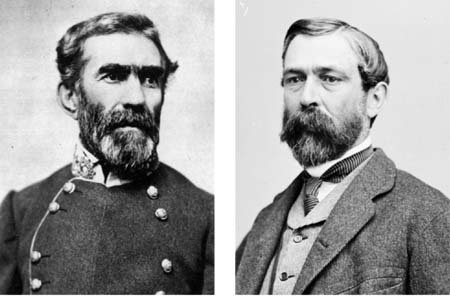

Recently detached from the Army of Tennessee, the Arkansas troops of Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Churchill’s division had not yet met their new commander when the division came under fire at Richmond, Kentucky, on August 30, 1862. No one recognized the bespectacled officer who appeared among them on horseback, urging them to charge the enemy. This was the way that the Arkansas soldiers became acquainted with Edmund Kirby Smith, a Southern general whose American Civil War career lasted from the opening campaigns of the war in Virginia in 1861 to the last days of the collapsing Confederacy in June 1865. In three years, he rose from the rank of major to that of full general, in charge of the vast, seemingly semi-independent Department of the Trans-Mississippi that came to be known as “Kirby Smithdom.”

Edmund Kirby Smith’s Early Years

Edmund Smith was born in St. Augustine, Florida, on May 16, 1824, to Connecticut natives Joseph Lee Smith and Frances Kirby Smith. Early during his childhood, Edmund’s family realized that the lad was nearsighted and would always need spectacles. Like many Victorian-era soldiers and civilians, he would avoid having his photograph taken while wearing glasses, but he depended on them when on the battlefield.

Several years of private schooling prepared him to enter the U.S. Military Academy at West Point in 1841. Edmund’s fellow cadets called him “Seminole” because the Second Seminole War was being fought in his native Florida.

Smith almost did not graduate from West Point. Although aware of the cadet’s nearsightedness, the school authorities did not raise the issue until his final year. When it looked as if he would be denied a commission in the army, Smith gathered testimony from administrators and teachers, including his instructors for riding and sword exercise, all of whom stated that vision had never interfered with his training or duties. This support was sufficient to allow Smith to join the 5th U.S. Infantry after his graduation in 1845.

The 5th Infantry was then stationed in Detroit. Among the officers of the regiment was Smith’s elder brother, Captain Ephraim Kirby Smith. As war loomed between the United States and Mexico, the 5th Infantry was soon transferred to Texas. The Smith brothers saw action in Texas on May 8-9, 1846, at Palo Alto and Resaca de la Palma, the first battles of the Mexican-American War. After transferring to the 7th Infantry, Edmund Kirby Smith earned two brevet promotions, to first lieutenant after the Battle of Cerro Gordo and later to captain after the battles at Contreras and Churubusco.

After the end of the Mexican War, Smith taught mathematics at West Point from 1849 to 1852. In September 1852, he was transferred to rejoin his old regiment in Texas. Promotion to captain came with a transfer to the 2nd U.S. Cavalry in 1855.

On May 13, 1859, Smith was part of an expedition led by Major Earl Van Dorn against the Comanche Indians in the Nescutunga Valley of Texas. Van Dorn’s troops attacked a ravine defended by the Comanches. Smith’s spectacles became so fogged or smudged that he did not see a warrior approaching him. His adversary fired a bullet that struck him in the thigh. Despite the wound, Smith stayed in the saddle for the rest of the battle. In the same action, future Confederate commander Lieutenant Fitzhugh Lee survived an arrow that tore through his body and protruded from his back.

Smith Joins the Rebel Army

In early 1861, Smith was in Texas as a recently promoted major in command of Camp Colorado. South Carolina had seceded from the Union the previous December, and now secessionist sentiment was sweeping across the South. By February, “secession fever” took hold in Texas. Colonel Henry E. McCullough (brother of the future Confederate Brig. Gen. Benjamin McCullough) arrived at Camp Colorado with several companies of state troops. On February 22, McCullough demanded that Smith surrender the post. Smith initially refused, but after some negotiation, he agreed to turn Camp Colorado over to the secessionists on the condition that he and his garrison troops be allowed to leave peacefully.

Smith resigned from the U.S. Army after learning of his native Florida’s secession; he then accepted a commission as a lieutenant colonel in the new Rebel army.

By June, Smith was a brigadier general, serving with Brig. Gen. Joseph E. Johnston in the Army of the Shenandoah, stationed west of Richmond.

In July, Brig. Gen. Irvin McDowell and 35,000 Union troops marched out of Washington toward Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard’s 22,000 Confederate troops, deployed 30 miles away at Manassas Junction, Virginia. Johnston and Smith, whose troops were stationed nearby at Winchester, rushed to join Beauregard.

Smith had to wait for enough cars and engines to carry his three regiments to Manassas. They boarded cars of the Manassas Gap Railroad at Piedmont Station at 2:00 AM on Sunday, July 21, and headed out toward the war’s first major battlefield.

Sergeant McHenry Howard of the 1st Maryland recalled that their train traveled slowly toward Manassas. It was just as well that the train did not move too fast: it was so packed with soldiers that many men had to ride clinging to the roofs of the cars. There were frequent halts, and each time, hungry soldiers spilled from the cars to hunt for blackberries growing in the right-of-way by the tracks. “On one of these occasions, I heard a voice exclaiming furiously, ‘If I had a sword I would cut you down where I stand,’ and raising my eyes, I beheld the crowd scattering for the cars before an officer striding up from the rear,” recalled Howard. The voice belonged to Smith, who the men were meeting for the first time. “So we straggled from the cars no more,” Howard said.

The train stopped at 1:00 PM a few hundred yards short of the railroad junction, according to Howard. His comrades stepped off the train and marched toward the sound of gunfire. Although the timely arrival of Smith’s men helped win First Manassas for the Confederates, the general saw little of the actual fighting.

Commanding the Army of the Shenandoah’s Fourth Brigade

Smith commanded the Fourth Brigade of the Army of the Shenandoah, which was composed of the 1st Maryland, 3rd Tennessee, 10th Virginia, and 13th Virginia Regiments, as well as the Culpeper Artillery. The general rode north towards the battlefront with Colonel Arnold Elzey’s troops at the head of the brigade. The troops had to contend not only with the suffocating heat of the Virginia summer, but also the thick dust churned up along the Manassas-Sudley Springs Road that led towards the rapidly unfolding battle. Smith arrived at 3:30 PM at Johnston’s headquarters at Portici, the home of Frank and Fannie Lewis. Fighting raged just to the north atop Henry Hill. Johnston was already drawing up plans for a possible retreat, since the Confederates were steadily giving ground in the face of the Union flank attack.

Smith led his troops west, following Colonel Joseph Kershaw and his South Carolinians. Smith was conferring with Kershaw about where to insert his troops when a stray musket ball struck him just behind the collarbone of his right shoulder. The bullet tore under the muscles of his shoulder blade. It missed his spine, and exited from his left shoulder. Elzey took immediate command of Smith’s regiments.

It looked as though the gunshot had dealt Smith a mortal wound. Indeed, he was reported dead, and press accounts of his death reached his family. John R. McDaniel, unsure from contradictory reports whether Smith was dead or not, sent his nephew to Manassas to bring his friend back either for a comfortable convalescence or a decent burial.

Despite the serious appearance of the wound, though, Smith suffered only relatively minor injuries. Smith recuperated at McDaniel’s home. He saw his own death notices in the newspapers. An even more inaccurate and widely circulated newspaper report had it that the Confederate general Kirby Smith was shot dead by his own nephew, Colonel Joseph Lee Kirby Smith of the 43rd Ohio.

“It behooves one to be killed occasionally to find out how many friends he has and how anxiously he can be inquired after,” he informed his mother in a letter. Tending the patient was a young woman named Cassie Selden. Having already been acquainted for several months, the two grew closer during the patient’s convalescence. They married on September 24, 1861, and ultimately had 11 children.

Promoted to major general on October 11, 1861, Smith assumed command of a division of the Army of Northern Virginia. His time in the Eastern Theater ended in February 1862, when he was sent to command the Department of East Tennessee.

Smith participated in a joint invasion of Kentucky in August 1862 with General Braxton Bragg, the commander of the Army of Tennessee. Kentucky had declared its neutrality in May 1861, but that effort was shattered when the Confederates seized Columbus on the Mississippi River four months later. Union troops then entered the northern part of the state, while Confederates occupied parts of the southern half of the state. When Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant captured Forts Henry and Donelson in northern Tennessee, Confederate forces withdrew from the state.

While Bragg’s main army marched from Chattanooga, Tennessee, Smith’s Army of East Tennessee departed from Knoxville on August 14. Smith bypassed the Cumberland Gap, which was held by Brig. Gen. George W. Morgan and his 7th Division of the Army of the Ohio. Morgan had occupied the strategic gap in June 1862 after outmaneuvering a much smaller force stationed at the gap.

Eyes on Lexington

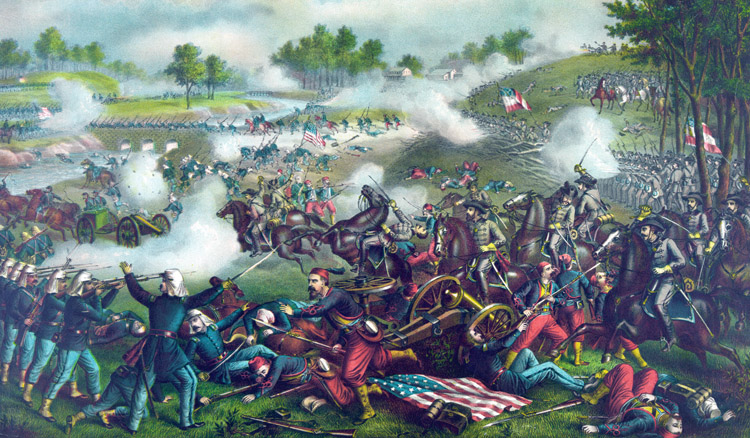

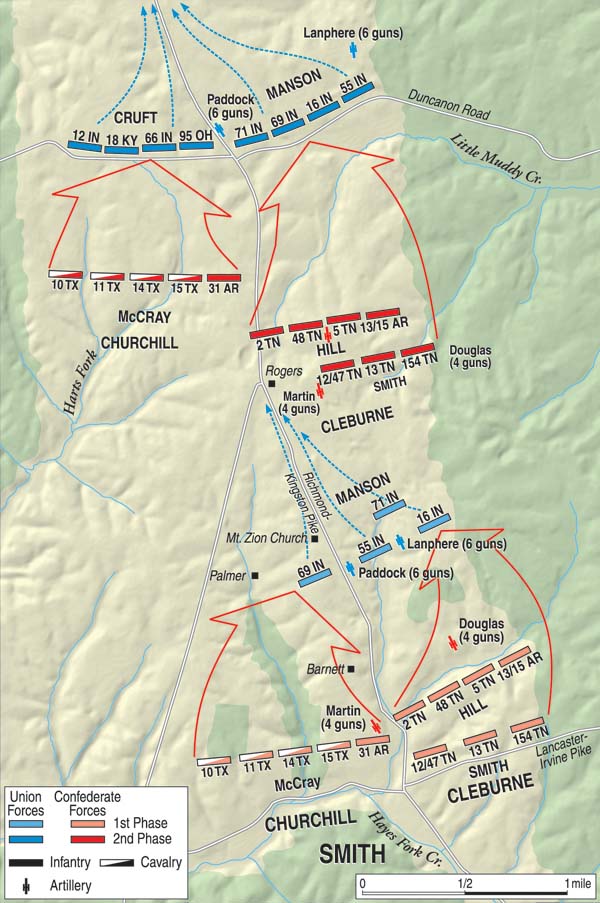

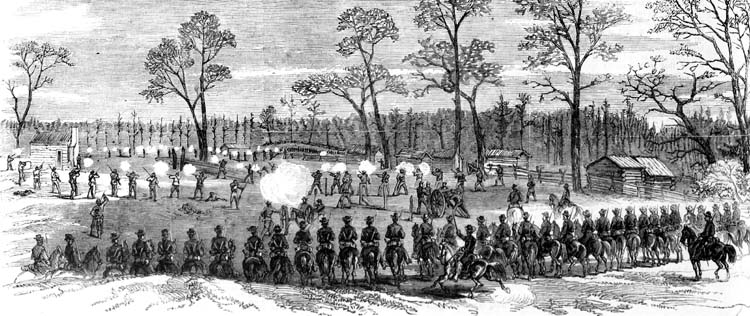

Smith’s objective was Lexington, Kentucky. On August 29, his troops approached Union Brig. Gen. Mahlon D. Manson’s 6,500 soldiers holding Richmond, Kentucky. Although Smith had 19,000 troops for the Kentucky campaign, they were spread out, leaving Smith fewer than 7,000 men to deploy for the looming battle.

Although only slightly outnumbering the Union force, the Confederates had a significant advantage in fighting experience. Smith’s soldiers were mostly veterans, while most of Manson’s men were emergency troops enlisted for periods as short as 10 to 25 days. Manson’s superior officer, Maj. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson, had serious reservations about how the green troops would perform in open battle, so Manson was under orders to avoid an engagement. If necessary, he was to withdraw to the Kentucky River to establish his defense.

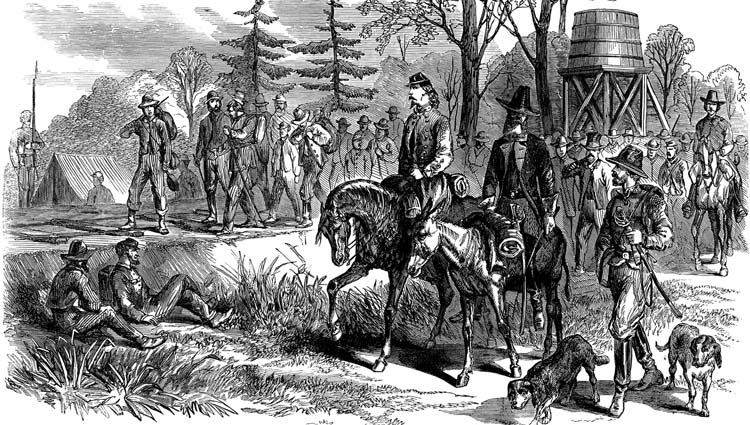

Manson, though, opted to take a stand at Richmond. The Rebels broke through and drove the green troops back three times. Smith was conspicuous on the battlefield. One witness recalled him “dashing about bareheaded [having lost his hat], in the thickest of the fights, cheering his men and being himself everywhere at the right time.” Among his command were “some Arkansas troops who did not know who he was, but recognized him as the person who led them so gallantly,” according to the witness. The Arkansas men raised “three cheers for the ‘man with the spectacles.’” When a soldier recognized Smith, he informed his comrades. Upon learning of the general’s identity, one of the Arkansas men shouted, “General, we’ve cheered your spectacles, and now we’ll cheer you.”

Smith won a much-needed victory at Richmond. Confederate casualties came to 451, compared with Union losses of 206 dead, 844 wounded, and 4,303 captured. Manson was among the captives.

How Edmund Kirby Smith Took Command of the Trans-Mississippi Department

With his troops’ momentum powered by their victory at Richmond, Smith’s army pushed Union forces out of Lexington and the state capital, Frankfort. The Southern Illustrated Newsof Richmond, Virginia, praised Smith after the Union state government of Kentucky fled the capital city. “The bogus legislature fled to Louisville, and the Confederate flag was displayed on the capitol of the state,” the newspaper wrote. “Everywhere the people are joining him…He seems to have effected a complete revolution.”

But the promise of a Confederate capture of Kentucky faded in the weeks after the fight at Richmond. After Bragg lost the Battle of Perryville on October 8 to Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell, Smith united his troops with Bragg’s at Harrodsville. Buell had failed to press Bragg’s outnumbered troops, and now that the scattered Confederate forces were assembled, Smith pleaded with Bragg to engage him again. “For God’s sake, General, let us fight Buell here,” he said. Bragg consented at first, but changed his mind and decided to withdraw his scattered Confederate forces from Kentucky, losing the confidence of his officers as a result.

Promoted to lieutenant general on October 9, 1862, Edmund Kirby Smith then took command of the Trans-Mississippi Department in January 1863, replacing Maj. Gen. Theophilus Holmes. The vast Trans-Mississippi Department, which included Missouri, Arkansas, western Louisiana, and Texas, covered more than 600,000 square miles. Its indeterminate bounds faded into the frontier, embracing the Indian Territory (Oklahoma), and hazy claims to New Mexico and Arizona. Nearly 2.8 million people lived within the department, but as much as half of the population were under Union occupation. Only Texas had an intact state government. The secessionist governments of Missouri, Arkansas, and Louisiana were all in temporary quarters after their state capitals fell to the Union. Many citizens, especially in Missouri and parts of Arkansas, were pro-Union, and secessionist morale in the department drooped as more and more territory fell to Federal forces.

When Smith assumed his new position, Holmes was shuffled off to command the department’s District of Arkansas. Major General John B. Magruder headed the District of Texas, New Mexico, and Arizona. The commander of the District of West Louisiana was Maj. Gen. Richard Taylor. The son of former war hero and U.S. President Zachary Taylor, Richard Taylor was an able officer, but he would come to disagree on strategy with Smith in the coming months.

Smith established his headquarters at Shreveport, the head of navigation on the Red River. A town of 2,200 people in 1860, Shreveport became the Confederate capital of Louisiana after the loss of Baton Rouge in May 1862, and the subsequent loss of the temporary capital of Opelousas.

The Red River’s name came from the reddish sediments washed into the river that gave it a clay-red color. Navigation on the river was long impeded by a tremendous log jam known as the “Red River Raft,” which was composed of a centuries-old tangle of fallen trees, accumulated soil, and new vegetation. In some places horsemen could ride across the river over the log jam. Once more than 100 miles long, the raft was partly cleared by the 1840s, allowing small steamboats to reach Shreveport. Some miles above that town, the river remained blocked by the accumulation of trees and vegetation.

During the first half of 1863, Ulysses S. Grant, now a major general, chipped away at the last Confederate-held stretches of the Mississippi River. Rebel control was limited to shrinking areas around their besieged strongholds of Port Hudson, Louisiana, and Vicksburg, Mississippi. Communication between the East and the Trans-Mississippi region was increasingly difficult. Battling large Union armies, and with the Union Navy blockading its coasts and slashing its way through the major rivers, the eastern Confederacy could spare little in the way of weapons or funding for the distant sideshow war fought west of the Mississippi.

If anything, the Army of Mississippi defending Vicksburg wanted the Trans-Mississippi Department to spare troops for it. Lieutenant General John C. Pemberton, the commander of the Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana, sought help from Smith, but Smith could send little aid to Pemberton. He ultimately did dispatch troops under Taylor and Brig. Gen. John G. Walker, but that alone was not enough to raise the siege.

After the surrender of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, Smith was stranded, with his department completely cut off from the rest of his struggling nation. Because there was no time to wait the necessary weeks for approval from Richmond for new initiatives, he had to take it upon himself to make increasingly important decisions without obtaining permission from the administration of Confederate President Jefferson Davis.

Richmond was aware of his unusual situation. Smith was promoted to full general on February 19, 1864. He also quietly received an unprecedented degree of military and political autonomy that turned his department into an essentially semi-independent domain of the Confederacy.

Such moves in a nation founded on principles of states’ rights and limited central government, even though made necessary by the war, could easily veer into illegal and unconstitutional grounds.

Davis and his cabinet were aware of the potential conflict between practical necessities and the rules of their constitution. Smith, in writing of the weight of his new responsibilities, likened his semi-autonomous domain to an empire. The Northern press, apparently led in this case by the New York Herald, referred to his department as “Kirby Smithdom.”

To chart a course of action, Smith convened a conference on August 15, 1863, with the state governors and influential figures of the Trans-Mississippi region in Marshall, Texas. The convention granted him control of the cotton industry to fight speculation and raise money for the war. It also recommended that Smith establish his department’s own diplomatic links with Mexico and France.

Early in 1862, with the United States embroiled in internal war and unable to enforce the Monroe Doctrine, Emperor Napoleon III of France found a pretext to launch a French invasion of Mexico. Smith sent agents to Mexico to establish good relations with the French invaders, as well as the Juarista governors of the northern states of Mexico.

Problems with Mexico

Trouble arose in November 1863, when the Confederacy funneled $16 million in funds to the Trans-Mississippi Department via the Mexican port of Matamoros. The merchant firm entrusted with handling the transfer seized the money, claiming it against debts owed to them by the Confederate States.

Smith responded with a ban on all cotton exports to Mexico, and froze all Mexican assets in Texas. Facing the loss of badly-needed revenue from the cotton trade, Mexican authorities worked out a solution with the Confederates. The funds were released upon assurances that the Confederate government would settle its debts, and trade resumed.

Besides communicating with French officials in Mexico, Smith opened direct contact with France, reminding them that in aiding the Confederacy, France would gain from the cotton trade and avoid having friendly Confederate Texas replaced with “a grasping, haughty, and imperious neighbor.” These overtures, however, were ineffective.

Without significant supplies from the East, the Trans-Mississippi Department had to supplement its meager manufacturing capacity by exchanging cotton for necessities purchased in Europe and run through the Union blockade. Smith created a cotton bureau to handle trade in this valuable commodity.

Economics and diplomacy were far from the only matters crossing Smith’s desk. In early 1864, the commander of the Trans-Mississippi learned of the greatest threat so far directed at his department, a Union offensive known as the Red River Campaign. Although the Lincoln Administration opposed the French invasion of Mexico, which flouted the Monroe Doctrine, Washington could not afford involvement in another war. But the Union Army could spare enough troops to invade Texas. Planting the U.S. flag along the Rio Grande would choke off supplies flowing into the Trans-Mississippi, and rattle the confidence of Napoleon III’s Mexican expeditionary force in the bargain.

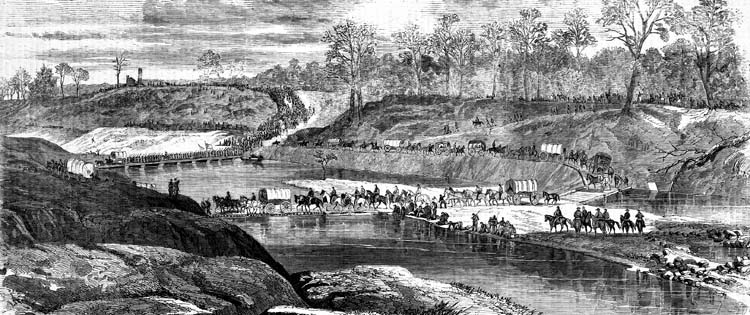

Lieutenant General Nathaniel P. Banks took command of the campaign against Confederate troops in the Red River area. The Red River offered the easiest route for a land invasion of Texas. Banks He would move up the Bayou Teche—a waterway through central Louisiana—from southern Louisiana with 17,000 men, and take the Red River port of Alexandria. At that location, Banks planned to meet Brig. Gen. Andrew Jackson Smith and 10,000 more men. Detached from Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s forces in Mississippi, Brig. Gen. Smith arrived in Alexandria aboard transports guarded by a fleet of Union Navy river gunboats under Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter. Another army, 15,000 men commanded by Lt. Gen. Frederick Steele, would move south from Little Rock, Arkansas, and join forces with Banks. They would capture Shreveport, and then push into eastern Texas.

Alexandria fell to Andrew Jackson Smith’s forces on March 18. By March 26, Banks and his contingent joined them. Banks’ combined force pushed toward Shreveport, but was immediately confronted with two problems. The water in the Red River was so low that Union gunboats could barely pass over the rapids above the town. Moreover, Brig. Gen. Smith’s 10,000 men were only on loan until April 15, at which time they were to head east for Sherman’s campaign against Atlanta.

Banks had more than 40,000 men. In contrast, Smith had only 30,000 troops in his entire department, and they were scattered from the Rio Grande and the Gulf of Mexico to the Indian frontier.

Taylor, who was in command of Confederate troops in Louisiana, fell back from Banks’ and Porter’s forces until halting at Mansfield, Louisiana, 20 miles from Shreveport. On April 7, cavalry units clashed at Wilson’s Plantation. Taylor telegraphed Smith, asking if he should risk battle at Mansfield. Smith did not immediately respond, so it was the next day before his courier reached Taylor.

More Trouble for Banks

Meanwhile, fighting erupted between Union and Confederate forces near Mansfield on April 8. Once the enemy forced his hand, Taylor committed his 8,800 men to the battle variously known as Mansfield or Sabine Crossroads. At the cost of 1,000 casualties, Taylor smashed Banks’ army, inflicting 2,900 casualties, while taking 20 guns and a train of 250 supply wagons. It was after the battle was won that Smith’s orders arrived, which were to avoid a clash with the enemy.

On April 9, Taylor followed up with an attack on Banks at Pleasant Hill. This time, Banks inflicted heavy casualties on the Confederates. When Smith reached the battlefield, he was alarmed at the state of Taylor’s battered army, and withdrew it to Mansfield.

Banks also was disheartened from a combination of two days’ worth of casualties, the failure of Steele’s troops to join his army, and the impending loss of Brig. Gen. Smith’s men. Banks ended his drive for Shreveport and withdrew down the Red River.

Taylor was a Louisianan, and his plantation had been looted by Union troops. Focused on his home state, he wanted to press Banks. Smith, with an eye on his whole department, ordered Taylor to send his infantry back to Shreveport before moving against Steele’s forces in Arkansas.

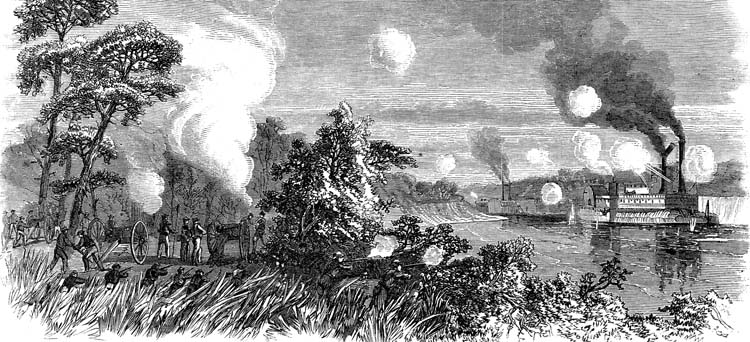

More troubles waited for Banks. The ironclad USS Eastport, a captured Confederate ship employed by the Union as a ramming vessel, sank after hitting a mine below Grand Ecore. Raised and patched up, the Eastportcontinued downstream, but the hull continued to leak. At last, on April 26, the Eastportran aground. The crew abandoned the steamer and blew it up.

When the Union gunboats neared Alexandria, the river was so low that the flotilla could not pass the rapids. It looked like the force was trapped and would fall into Confederate hands. The Confederates blocked the Red River for several days, and managed to destroy five Union vessels.

The Union’s other steamers were saved by Colonel Joseph Bailey, who directed the construction of several wing dams. The dams, each stretching only partway across the river, which backed up enough water that the flotilla could steam over the rapids.

The Red River Campaign was a fiasco for the Union, but it brought much trouble to Smith, as well. Back in March, he ordered 150,000 bales of cotton burned to keep the vast haul out of enemy hands. Sixty million dollars worth of valuable cotton, which might have been traded for arms and supplies, went up in smoke.

Taylor resented Smith for sending his troops to Arkansas without him. After a heated exchange of letters and statements, Taylor resigned rather than continue to serve with his commander. Considered too valuable an officer to lose, Taylor was promoted to lieutenant general and assigned to command the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana.

The spring of 1865 brought the end of the Confederacy. The main eastern armies under Generals Robert E. Lee and Joseph E. Johnston surrendered on April 9.

For a brief time, though, diehard secessionists hoped that the bid for Confederate independence could survive in “Kirby Smithdom.” Smith met with Trans-Mississippi state officials in Shreveport, and at a large public meeting, crowds of citizens declared support for the idea. It seemed possible that the Confederate cabinet and president, who had fled from Richmond ahead of the Union Army, would head south and find their way to Cuba. The secessionists’ hope were dashed when news reached the west that Union troops had captured Davis and his party in Georgia on May 10.

Although Smith and some high-ranking officials projected confidence about continuing the war, most of the Trans-Mississippi did not share their optimism. Despair swept through the western army. Detached from the rest of the Confederacy since Vicksburg, the soldiers and citizens in the Trans-Mississippi felt that they were completely stranded and alone by the end of April.

Military officers in Texas bombarded Smith with pleas for help as Union forces pressed toward them and their own soldiers deserted in droves. On May 20, Smith left Shreveport to establish a new headquarters at Houston. From there, he hoped to rally the remaining Confederate forces in Texas.

Arriving at Houston on May 27, Smith found his command was rapidly falling apart. Rather than heed his orders, most of his soldiers left the army and headed for their homes.

Moving on to Galveston, Smith found affairs were no better. He learned that Magruder had traveled to New Orleans on his own to negotiate a surrender of the Trans-Mississippi Department. Magruder signed the surrender papers on May 26.

The End of the War for Smith

Recognizing that the end was at hand, on June 2, Smith boarded the USS Fort Jackson in the harbor of Galveston. Also present were Magruder and Union Brig. Gen. Edmund J. Davis. Aboard the steamer, Smith signed papers surrendering the troops remaining in his department. This ceremony practically ended the Civil War, although a small Confederate force of Cherokee troops under Brig. Gen. Stand Watie held out until June 23.

To avoid the possibility of arrest for treason, Edmund Kirby Smith spent several months after the surrender in Havana. He returned to the United States and took the oath of allegiance in November 1865. The U.S. Army was of course forever closed to him, so Smith first turned to the business world, accepting the presidency of the Pacific and Atlantic Telegraph Company. That company failed, and the former commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department considered becoming an Episcopal minister.

In the end, he returned to the field of education, and spent the rest of his life as a college teacher or administrator. In his final years, he was a professor of mathematics at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tennessee. When Edmund Kirby Smith died at the age of 69 in 1893, he was the last surviving full general of the Confederacy.