By Eric Niderost

It was raining heavily, a deluge of almost Biblical proportions that hammered down on the exhausted men of the Union’s Army of the Tennessee. They had just fought a very bloody battle on April 6, 1862, with Confederate forces, the bloodiest to date in this fratricidal war, and had been pushed back almost to the Tennessee River. The bluecoats were forced to bivouac as best they could in a downpour that did little to mute the horrors of that evening.

It was pitch dark, an inky void that was briefly illuminated by bolts of lightning that suddenly veined the sky at intervals. But perhaps the darkness was a blessing, because survivors could not see the 2,000 corpses that lay thickly on the bloodied ground, some of them horribly eviscerated, and others without a limb or even a head. But if they could not see, they could still hear. Hundreds of wounded and dying were lying where they fell, moaning and screaming with pain in the darkness. Their agonized cries were mingled with the low-pitched grunts of wild pigs rooting around and feasting on the putrefying corpses. Union gunboats added to the cacophony, creating a terrible din by shelling the seemingly triumphant Confederates.

Major General Ulysses S. Grant, commander of the Army of the Tennessee, had originally planned to sleep under the spreading branches of a large oak tree, but slumber proved impossible under these conditions. Torrential rains were one thing, but Grant was experiencing excruciating pain from a leg injury he had sustained a couple of days earlier. Seeking better shelter, he used a crutch to hobble over to a log house that was serving as a field hospital. He immediately realized it was the wrong thing to do. Medicine in the American Civil War was still a primitive affair, and surgeons amputated arms and legs on a regular basis. Sweating surgeons, daubed with gore, grimly plied their trade as they sawed bones and tied off arteries time and again.

Grant turned away and hobbled back to his oak tree, unable to witness even a minute more of that sanguinary hell. Brig. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman, one of his subordinate commanders, found him under that tree a short time later. Grant huddled there, sodden collar turned up in a futile attempt to ward off the rain, his saturated slouch hat pulled down over his head. Grant took a drag on a cigar, the glowing orange end a tiny beacon of light in the gloom, though he also had a lantern in his other hand.

Sherman was unsure about what Grant was going to do. Some of the officers felt the Army of the Tennessee had to retreat or risk annihilation. Sherman, whose nickname was “Cump” from Tecumseh, decided to sound Grant out about the matter. “Well,

Grant, we’ve had the devil’s own business,” Sherman observed. “Yes,” Grant admitted, taking another puff of his cigar, “lick ‘em tomorrow though.”

In many ways, this was Grant’s defining moment. He had been taken by surprise, caught off guard, and his Army of the Tennessee had been badly battered and forced back to the river after heavy fighting. On the surface, at least, it looked like the Confederates were on the verge of a great victory. Grant’s statement was typical of the man. It was brief and laconic, but precise and to the point, and provided a glimpse of his true greatness as a general. He had carefully analyzed the situation, weighing both pros and cons, the possibilities of victory or defeat, and determined they would win the next day.

Apart from some distinguished service as a young lieutenant in the Mexican-American War, Grant’s military career was anything but auspicious before 1861. Posted to frontier outposts in the West, separated from his beloved wife and children, Grant began to seek solace in the bottle. Evidence seems to indicate that Grant was a binge drinker, not an alcoholic in the classic sense of the word. With little to do but pine for his family, Grant turned to the bottle as a welcome relief from the deadening ennui. Yet he could be perfectly sober for months at a time, and with the care and support of his wife Julia, and later his aide and close confidant Captain John Rawlins, he could stay on the wagon more or less permanently.

Yet the label of drunkard became an albatross around his neck long after he had given up the bottle. Buried for a time, accusations of drunkenness would surface periodically, even as he became famous though a string of victories in 1862. For the most part they were put forward by jealous rivals or others who had some axe to grind, but luckily President Abraham Lincoln ignored these calumnies.

Grant resigned his commission in 1854 and rejoined his family in Missouri. The rest of the decade was one of failure and bitter disappointment as Grant tried various occupations without success. He tried his hand at agriculture, but after some initial progress he failed as a farmer. To make ends meet he was reduced to selling firewood in the streets of St. Louis. Grant also had to endure a measure of humiliation when he encountered Army officers he had known while serving in the Mexican-American War and on other assignments.

These former colleagues were shocked when they saw Grant hawking firewood, dressed in a shabby old Army overcoat and looking like a common peddler. When one astonished onlooker asked Grant what he was doing, he replied, “Solving the problem of poverty.”

He hit bottom in 1857, when he pawned his watch to buy Christmas gifts for his family. By 1860 he threw in the towel and took his family to Galina, Illinois, where his father made him a clerk in a leather goods store.

It looked as if Grant was condemned to live out his life as a failure, dependent on the charity of others to make a living. That all changed when the American Civil War broke out in April 1861. The U.S. Army, which was generally called the Federal or Union Army, greatly expanded. To fill its ranks, there was a need for trained officers. Yet, ironically, Grant continued to have bad luck, at least initially. He was appointed a mustering officer, but it was a temporary position that ended in two weeks.

Still hopeful, Grant wrote to Lorenzo Thomas, the adjutant general of the army, seeking a commission. “I feel myself competent to command a regiment if the President, in his judgement, should see fit to entrust one to me,” said Grant, putting his best foot forward. He received no response; undeterred, Grant visited the headquarters of George B. McClellan, who at the time was a brigadier, seeking a staff appointment.

Grant patiently waited to see McClellan that June of 1861 only to cool his heels in the general’s waiting room for two days without an audience. Somebody finally put Grant out of his misery by informing him the general had gone out. That seemed to be McClellan’s favorite tactic when he wanted to avoid seeing someone.

Grant went home disappointed, but his luck was about to change. Not long after the McClellan episode Governor Richard Yates of Illinois offered him the colonelcy of a new body of men that was being formed, a regiment eventually called the 21st Illinois. Grant accepted with alacrity.

The newly minted colonel did well in his new post, but he was surprised to learn only a month or so later he had been promoted once again, this time to the rank of brigadier general. Elihu Washburne, a U.S. Representative from Illinois and a Republican who had Lincoln’s ear, had been his benefactor this time. As a brigadier, Grant found himself in charge of four regiments, totaling 4,000 men.

Although his tenure as colonel had been brief, he did learn a valuable lesson when he was ordered to capture Thomas A. Harris, a brigadier general in the pro-Confederate Missouri State Guard. Harris’s 1,200-man mounted force was staging hit-and-run raids on isolated Union outposts. Grant found he was more than nervous, and his fears grew as he approached the place where Confederate raiders were said to have an encampment.

Grant was a seasoned Mexican-American War veteran, but then he had been a mere lieutenant. Now he was responsible for the lives of many men, and that made a difference. He tried to fathom Harris’s intentions. Would Harris turn the tables and ambush him? His anxiety was such that he admitted in his memoirs his heart was in his throat.

To Grant’s great relief Harris had retreated. “My heart resumed its normal place,” Grant later recalled. “It occurred to me at once that Harris had been as much afraid of me as I had been of him.”

It was a kind of epiphany for Grant, a profound realization that he remembered throughout the war. The Confederates were human beings just like their Northern opponents, not invincible foes with unlimited resources at their command. McClellan, the so-called Little Napoleon, was slow to recognize this central truth. He was overcautious, always believing he was vastly outnumbered, and constantly calling for heavy reinforcements. At one point he was held up by the Confederates alleged superior artillery, only to discover they were so-called Quaker guns, which were actually painted logs.

Ironically, his genuine disinterest in a military career made Grant a great general in some respects. Grant had been forced to go to West Point by his domineering father. “Military life had no charms for me,” Grant once said. Because he was a reluctant soldier, he did not constantly yearn for military glory like many of his colleagues. Union generals tried to emulate the great captains of the past, studying every move in hope of gaining similar fame.

Grant was aware of this trend and avoided it. “Some of our generals failed because they worked out everything by rule,” wrote Grant. “They knew what Frederick the Great did at one time and Napoleon at another. They were always thinking what Napoleon would do. Unfortunately for their plans, the rebels would be thinking about something else.” Grant did not scorn the lessons of the past, but he recognized that new inventions, such as the steamboat and the railroad, required new paths of military thought.

By early 1862 Union plans went ahead for what might be called “river wars.” The natural focus was the Mississippi River, the magnificent “Father of Waters” that flowed through the heart of the Confederacy on its way to the Gulf of Mexico. Near its end was the city of New Orleans, the South’s greatest port and its largest city. Capturing New Orleans was one thing, but if the entire length of the Mississippi could be controlled by the Union, the Confederacy would be cut in half.

Though this divide-and-conquer scheme was the heart of Union Western strategy, other waterways were not forgotten. The Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers were fluid gateways to the Rebel states of Tennessee, Alabama, and Mississippi. Grant made his headquarters at Cairo, Illinois, the southernmost point of the Union and an important intersection where the Ohio River emptied into the Mississippi.

Besides being natural gateways into Dixie, the Cumberland and Tennessee Rivers meandered through one of the principal grain-growing and iron-producing areas of the Confederacy. The iron works at Clarksville on the Cumberland was vitally important, while the city of Nashville on the same river was major supply depot for Confederate forces.

The Confederates were well aware of Union plans, at least in broad terms. Confederate General Albert Sydney Johnston, a soldier of some reputation before the war, headed the Western Department, and he was tasked with forming a defensive line that would stop Union thrusts south. The left flank defenses were anchored on the Mississippi River by a fortress in Columbus, Kentucky, while the right flank defenses rested on Bowling Green, situated in the central part of the state.

But the Confederate defensive line was vulnerable in its center. The center was held by Fort Henry on the Tennessee River and Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Both were slapdash affairs, badly sited and badly constructed. Fort Henry was the more poorly constructed and sited fortification. They were the Confederate line’s weakest links, essentially twin Achilles’ heels that would be tempting targets to any Union general with the strategic vision, boldness, and offensive spirit to recognize their vulnerability.

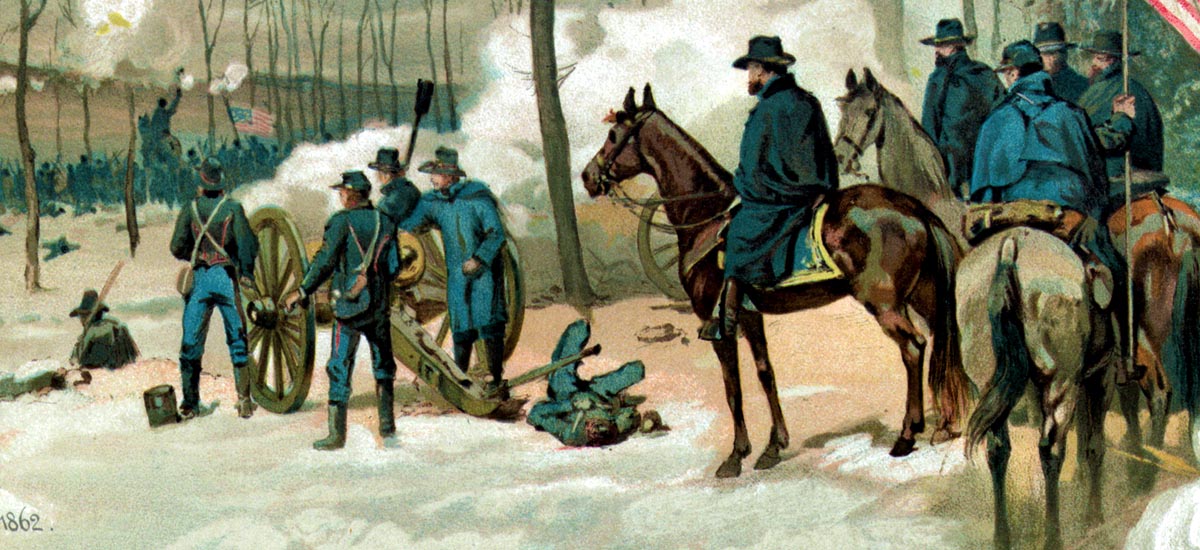

Major General Henry Halleck, Grant’s immediate superior, ordered an advance on Fort Henry, which should be “taken and held at all hazards.” Grant, long straining on Halleck’s leash, could now go forward. Fort Henry was considered the easier of the twin forts because it was actually lower than the surrounding hills, and when the river was high, as it was in the winter of 1862, was prone to flooding.

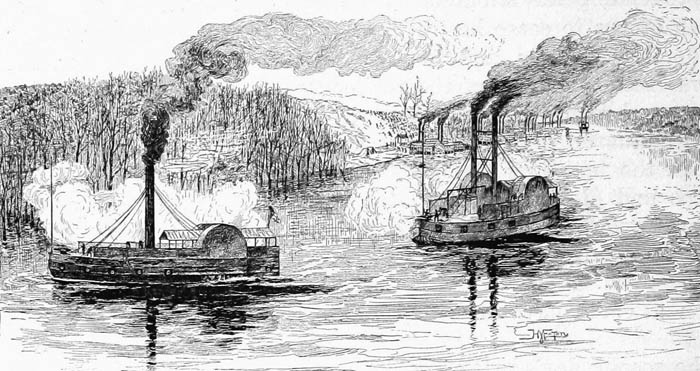

When Grant visited his headquarters in Cairo he would from time to time gaze out the window at the fleet of Union gunboats that lay at anchor nearby. Instinctively, he knew that these great aquatic beasts, ungainly but powerful, represented a new weapon in his hands that was uniquely adapted to this river campaign. Flat bottomed, wide beamed, and propelled by steam-powered paddle wheels, each vessel boasted 13 guns that provided a powerful sting. The gunboats were also protected by sloped iron plates up to 2.5 inches thick, which gave them a nickname, “Pook’s Turtles,” after naval architect Samuel Pook. They could take on most anything the Confederates had to offer.

Grant formed a solid working relationship with the gunboat fleet commander, Flag Officer Andrew H. Foote. Luckily, Foote was an energetic, offensive-minded officer who shared Grant’s strategic vision. The plan to take Fort Henry was simple and straightforward. Foote’s flotilla would bombard the fort at close range, and Brig. Gen. John McClernand would take an infantry division and envelop Fort Henry from behind, sealing off any possibility of escape.

The Union infantry became bogged down in the dense forests and rain-saturated roads of the region, so its progress was slowed. In this case, it did not matter: Foote’s gunboats did the job and battered Fort Henry into submission. The Confederate fort surrendered, but after the white flag was hoisted the Federals found to their surprise it had been manned by a skeleton garrison. Approximately 2,500 troops had been evacuated to Fort Donelson, 11 miles away.

Nevertheless, Grant’s taking of Fort Henry was a magnificent achievement, but the general wasted no time in proceeding to Fort Donelson. Grant was not about to rest on his laurels. Fort Henry was taken, but how long was it going to take for the stronger fort to fall?

Fort Donelson proved a much tougher nut to crack, but it fell on February 16, 1862. At one point the Confederates made a surprise attack on Union lines in a desperate bid to break out. The effort did not succeed, but the attack left at least some of the Union forces demoralized. Some Confederate soldiers had been captured, and Grant asked to have a look at their knapsacks. When opened up, they were found to have three days of cooked rations.

Some Union officers interpreted this as proof the Rebels were going to stand and fight. Grant begged to differ, saying, “They mean to cut their way out.” He admitted that “some of our men are pretty badly demoralized, but the enemy must be more so, for he has attempted to force his way out but has fallen back; the one who attacks first now will be victorious.”

In the end, Fort Donelson surrendered. Brig. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, the Confederate commander, knew Grant before the war, and there was genuine respect and admiration between the two men. Grant was magnanimous as a victor, always reminding his men that the Confederates also were Americans. But he had little stomach for the “moonlight and magnolias” romantic ethos that came from the tradition of Southern chivalry.

There would be no “knightly” courtesy; Grant demanded unconditional surrender from his vanquished foe. Buckner, who protested, had little choice but to agree. Grant’s army captured 15,000 Confederate prisoners as well as a large quantity of commissary stores, weapons, and artillery. The fall of Forts Henry and Donelson was the best news the North had had in months, and immediately catapulted Grant into the national spotlight.

Halleck planned a deeper thrust into the heart of the Confederacy. The fortress town of Corinth, Mississippi, near the Tennessee border soon became a primary objective. It was the crossroads of two vitally important railroads, the Mobile & Ohio and the Memphis & Charleston. These railroads were important communication links as well as conduits to ship supplies and men from the western parts of the Confederacy to the Eastern Seaboard.

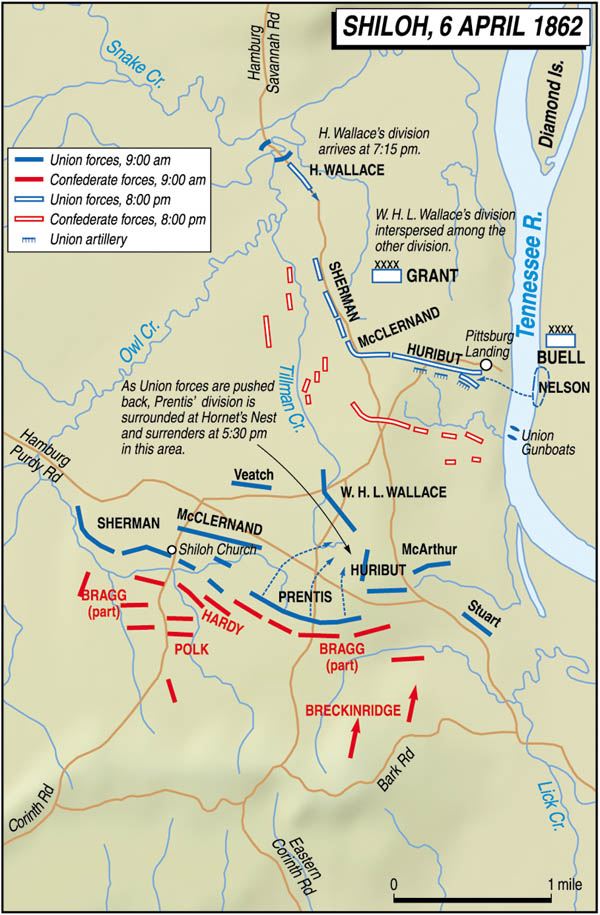

As Union plans matured, it was decided that Grant’s 42,000-man Army of the Tennessee would proceed down the Tennessee River, calling a temporary halt at an old steamboat stop called Pittsburg Landing. Only 20 miles from Corinth, Pittsburg Landing would be a staging area for a major advance on that city. The pause was necessary because Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s 37,000-strong Army of the Ohio was scheduled to rendezvous there as soon as it could arrive from Nashville.

Once Grant’s and Buell’s armies were combined, they would be a juggernaut and surely outnumber anything the Confederates could scrape together. Grant and some of his subordinates, such as the irascible Sherman, seemed to be in an ebullient mood. Buoyed by his recent successes, Grant was sure Corinth would be an easy objective. Grant would soon discover, though, that he had grossly underestimated his opponent.

Pittsburg Landing was a high tableland, where raw nature and cultivated farmland existed in seeming harmony. Graceful trees spread their branches atop high ridges, dramatically spiking the sky, and dense forests contrasted with the cultivated fields and orchards of cherry and peach. It was spring, but the next day this terrestrial paradise would soon be transformed into a nightmare vision of hell.

The Pittsburg Landing encampment held five of the Army of the Tennessee’s six divisions, a neat if sprawling tent city that stretched two to three miles from the Tennessee River to a rough-hewn log Methodist church called Shiloh. Ironically, the name was taken from a Hebrew term for peace. The Union 6th Division, which was led by future Ben Hurauthor Brig. Gen. Lew Wallace, was located five miles north at Culp’s Landing. The Pittsburg Landing site had natural features that lulled the Federals into a false sense of security. The Tennessee River guarded the eastern flank, Snake Creek hemmed in the western approaches, and Owl Creek blocked any attack from the north. The only possible way an enemy could attack was from the south, and if the bluecoats had thrown up some defensive works there, the camp would have been nearly impregnable.

Grant decided not to fortify the Pittsburg Landing camp for a variety of reasons that seemed valid at the time, but in retrospect they nearly brought on disaster. For one, he did not expect his army to stay in the area long, so there was no need for such precautions. Moreover, Grant was a firm believer in the offensive spirit, and he therefore maintained that in this particular instance entrenchment would be counterproductive to the men’s morale.

There were also regiments under his command who were little better than raw recruits; some had received their muskets only a few days before. Grant did not want them to trade their new weapons for spades and axes. It was drill, not digging, that would mold them into soldiers. Above all, though, Grant believed the Confederate forces in the area were a broken reed, demoralized after the twin defeats at Forts Henry and Donelson.

For all of Grant’s developing brilliance, he made a terrible, and nearly fatal, miscalculation. Confederate General Albert Sydney Johnston was not going to passively stand by while the Federals marshaled superior forces against him. Johnston gathered all the forces he could, some from as far away as the Atlantic seaboard, and began planning for a surprise offensive. If he could badly defeat, or possibly even destroy, Grant’s army the Northern cause would receive a crippling blow.

Luckily for the Union cause, one brigade commander, Colonel Everett Peabody, did not share his superiors’ complacency about the weakness of Confederate forces. He was part of Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss’s 6th Division, yet another complacent Federal officer. Peabody was not so sure, and so on his own initiative he sent out a patrol, five companies from the 12th Michigan and 25th Missouri, in the wee hours of the morning.

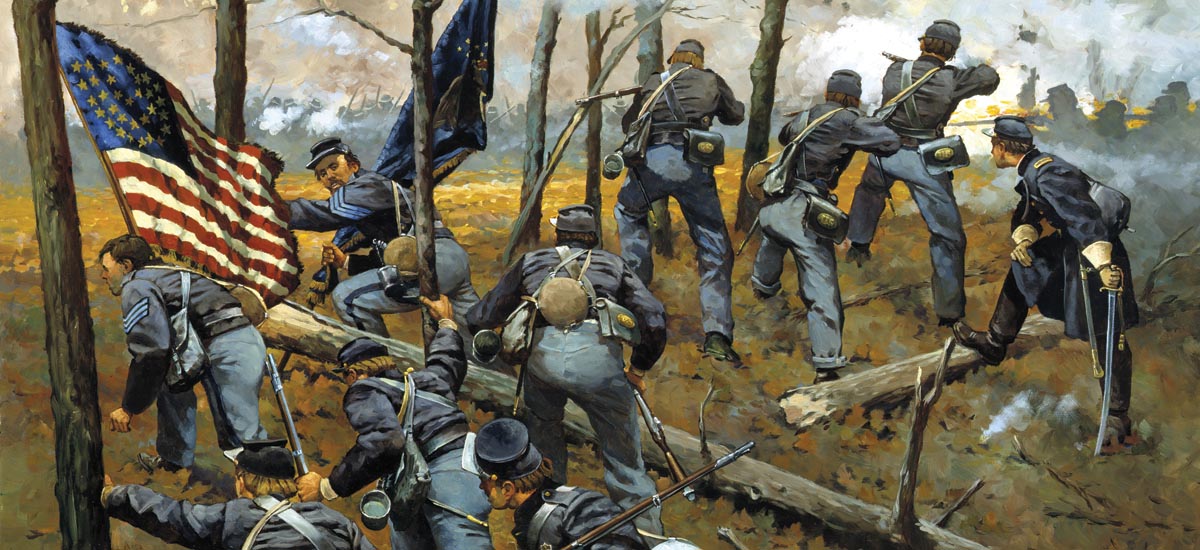

It was 5 am when they made contact with the cutting edge of the enemy assault force, 9,000 Confederates under native Georgian Maj. Gen. William Hardee. The patrol fought hard, stubbornly contesting every foot of ground, but the sheer weight of numbers forced them back. The sound of gunfire alerted Prentiss, who sent reinforcements from the 16th Wisconsin and 21st Missouri to aid the beleaguered patrol.

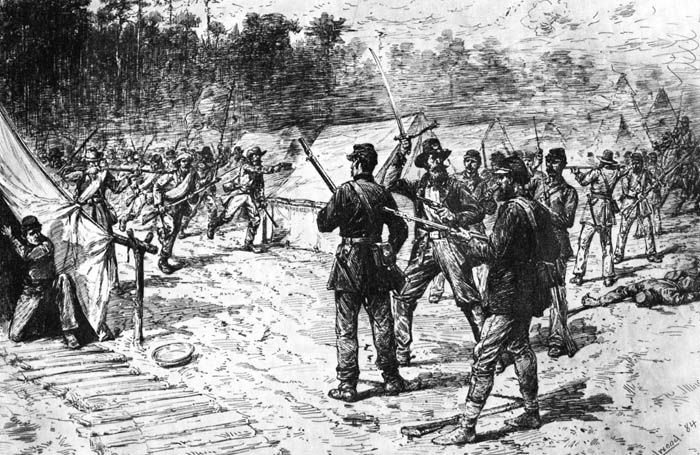

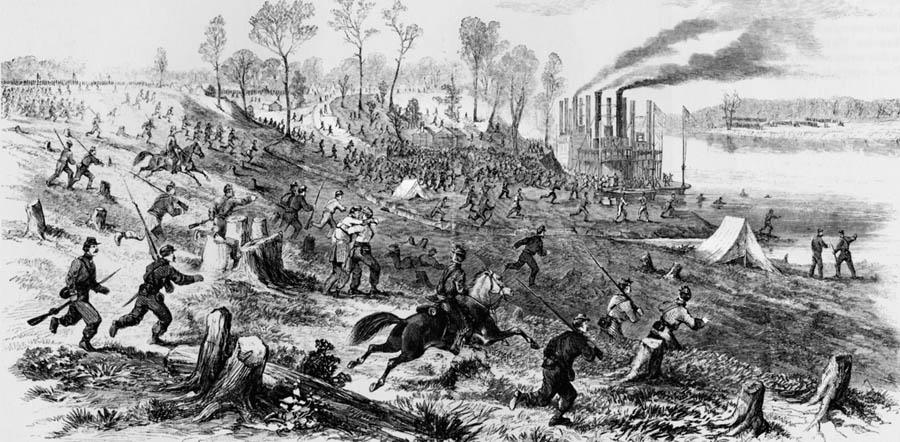

But the contest was too unequal, the numbers too great, to delay the inevitable outcome for long. The Union skirmish line, which acted as a dam, gave way. The shattered remnants of the four Union regiments were forced into a headlong retreat. Right behind them was a Confederate juggernaut that carried all before it. Long lines of gray and butternut-clad Confederate soldiers swarmed out of the woods, filling the air with the angry screams that later would be dubbed the Rebel Yell. The gray tidal wave was accompanied by regimental bands playing “Dixie.” Yet before long such music was all but muted by the staccato sounds of rifles and the deafening roar of smoothbore and rifled artillery.

The shattered Union patrol, stumbling in their haste and running in great disorder, passed through the main camps of both Prentiss’s 6th Division and Sherman’s 5th Division. The fugitives filtered through the 53rd Ohio’s camp, one of Sherman’s regiments, and at the moment the general himself was coming up to see what was going on. Sherman raised his telescope to scan the woods, sweeping the clumps of trees for signs of the enemy

Sherman got more than he bargained for. A Union officer shouted, “General! Look to your right!” and Sherman complied. It was a sight that would have startled even an old campaigner like Sherman. An entire Confederate brigade came storming out of the forest, not 50 yards away. At the same time a volley of bullets peppered Sherman’s position, killing an aide who was at Sherman’s side. The general himself was hit by a piece of buckshot in the hand and later received a spent bullet in the shoulder.

“My God,” Sherman exclaimed, “we are attacked!” Sherman wheeled around and galloped back, not only to escape the surging Rebels, but to rally the rest of his division for the onslaught. In the early stages of the battle confusion reigned among the Union soldiers. Some accounts contradict each other, but at least some Federal soldiers had been caught in their tents, lazily taking it easy or eating breakfast. “[Bullets] came whistling through our tents,” recalled 2nd Lt. William Rowley.

Grant was at his headquarters in Savannah, about nine miles downriver. He had just sat down to breakfast with some of his officers when the sound of distant rumbling could be heard in the direction of Pittsburg Landing. Grant was just about to drink a cup of coffee, but on hearing the unnatural thunder he placed his cup down. He listened a moment, then jumped up from the table and quietly said to his staff, “Gentlemen, the ball is in motion,” he said. “Let’s be off.”

Grant knew the sound was artillery, and it was clear a major battle was developing. He hurriedly wrote orders, including a missive to Brig. Gen. William “Bull” Nelson. Nelson, who had recently arrived at Savannah, commanded the advance guard of Buell’s Army of the Ohio. Grant ordered him to march to Pittsburg Landing, but on the opposite side of the river. Once he arrived, he would be ferried over to the battlefield.

Within 15 minutes the general, staff, orderlies, clerks, and horses were aboard the steamship Tigressand on their way to Pittsburg Landing. The commanding general arrived at 10 am. He was gratified to see that the troops—at least, most of them—were fighting hard under tremendous pressure from wave after wave of Rebels. A few thousand, mostly the raw recruits who had never seen a gun fired in anger, huddled beneath the bluffs near the landing for safety, but the rest were performing prodigies of valor. Grant was still nursing his leg, now swollen and extremely painful, and so agonizing he could not walk without the aid of crutches.

Undaunted, Grant had himself hoisted onto his horse, his crutch tied to his saddle. His injury was so bad it could have given him an excuse to stay at the landing in relative safety. This was not his style; he had to personally see what was going on. He had a quick conference with Sherman, who brought him up to date and gave him an accurate appraisal of the situation. Sherman was an inspiration to his green troops, although at the moment he looked anything but a conquering hero: covered in dust, his arm in a sling from a bullet wound, and a bloody bandage wrapped around his hand.

Several Union officers provided exemplary leadership that bloody day, including Sherman and Prentiss, but the real rock of Shiloh was Grant himself. He seemed not only one person but several, appearing as if by magic where the fighting was the heaviest. Minie bullets whistled through the air like swarms of angry bees, but he paid them no heed, calmly issuing orders as if the occasion was a peacetime review. He radiated confidence, and his straightforward, positive demeanor gave fresh heart to his men.

At one point a courier, having just delivered a message, had his head blown off moments later. Grant was sprayed by the man’s blood, but the general was unfazed and showed no emotion. “Not beaten yet by a damn sight,” he mumbled, as if refusing to believe the soldier’s sudden death might presage his army’s defeat and symbolic demise.

Prentiss’s division had been driven back to a sunken wagon road, a rutted, muddy, nondescript path that paralleled the Confederate front. There was a patchy stretch of woodland to its rear, and in the front brambles formed a prickly barrier to its front. It was there that Prentiss decided to make his stand. A short time earlier he had been visited by the commanding general, who told him to hold fast.

The remnants of Prentiss’s 6th Division were joined by several brigades from Brig. Gen. W.H.L. Wallace’s 2nd Division. The bluecoats entrenched, and for the next six hours refused to be dislodged in spite of equally heroic headlong assaults by the Confederates. The fighting was fierce; bullets flew so thickly they were like angry insects, giving the road the name “Hornets’ Nest.”

Federals from Brig. Gen. Stephen Hurlbut’s 4th Division deployed on Prentiss’s left where they defended a 10-acre peach orchard. The blooming trees with their delicate petals formed a dramatic contrast to the bloody carnage that occurred in that ordinarily tranquil place. Johnston was near the orchard when he was hit in the knee by a minie ball. He scarcely felt the wound for the adrenaline of battle numbed the pain. He bled to death within minutes.

As the Federal right and left bent back forming a salient, Prentiss and his men found themselves dangerously exposed. Confederate General P.T.G. Beauregard took command after Johnston’s demise, and he realized that the Hornets’ Nest must be taken. He assembled no fewer than 62 artillery pieces for the task. These iron monsters spewed a hurricane of shot and shell at 300 yards.

Hurlbut’s men were forced to give way as this same shot and shell scythed through the packed blue ranks. W.H.L. Wallace’s division fared no better, ripped to pieces to such an extent it lost its cohesiveness as an organized unit. Wallace tried to retrieve the situation, but in an attempt to rally his troops he was mortally wounded with a bullet to the head

Confederate attacks ground on, pushing Grant’s Army of the Tennessee back foot by foot, yard by yard. These gains were not without cost. Confederate General Braxton Bragg hurled wave after wave of graybacks against the Union lines in the Hornets’ Nest. Yet these nearly suicidal frontal attacks initially achieved nothing.

After the other Union divisions had been forced back, Prentiss and his bloodied bluecoats held the salient for two hours alone. But at last flesh and blood could stand no more. Prentiss surrendered himself and his approximately 2,200 men, which was half of the division’s original strength.

Johnston’s original plan was to attack on Grant’s left flank by the Tennessee River, separating the Federals from their so-called brown-water navy steamships and the possibility of escape. Once pushed back from the river, they could be forced inland and eventually end up in the swamps, their backs to Owl Creek. If that happened, surrender would almost inevitably follow.

But Johnston had not anticipated such a spirited Union defense. Also the Confederate general had formed his troops into a clumsy, layered offensive attack formation. Hardee’s division was the vanguard, the spearhead of the assault, and immediately behind him were General Braxton Bragg’s 11,000 troops. The third rank featured two corps led by Maj. Gens. Leonidas Polk and John Breckinridge.

But like their Federal counterparts, not all gray troops were seasoned soldiers. When they advanced, they tended to get bunched up, and units from different divisions intermingled. Also, as they passed through abandoned Union camps, they could not resist the temptation to loot. Even at this early stage of the war, the Federal soldiers had better creature comforts, such as blankets and food, which the graybacks desired. By the late afternoon Grant had pieced together a decent defensive line, and the fighting ended for the day. The Federal army had been pushed back about two miles, but the vital Pittsburg Landing was still in Union hands. Still doggedly optimistic, Grant personally visited each of his subordinates to tell them to be ready for a major offensive the next day.

Late in the day Buell showed up for an impromptu conference with Grant. Buell scanned Pittsburg Landing and what he saw appalled him: the seeming chaos, the bewildering confusion, the hundreds of green and badly frightened troops still trying to keep out of harm’s way. Buell did not beat around the bush, but asked Grant about his plans for retreat.

Grant must have been incredulous, but answered calmly, “I haven’t despaired of whipping them yet!” This was not arrogance, wishful thinking, or bravado. It was an insightful and accurate assessment of the overall situation. Lew Wallace’s division, which supposedly had taken the wrong road, finally arrived. In addition, three divisions of Buell’s Army of the Ohio had been ferried across the Tennessee River before daybreak. These fresh divisions took up positions on the Union left for the second day of the battle.

That gave Grant 25,000 fresh soldiers who would join his 15,000 survivors of the first day. Beauregard probably had 25,000 troops available for action on the second day, so the Federals would have numerical superiority. Even though he made the initial mistake in underestimating the enemy, Grant redeemed himself by his calm, rational demeanor under pressure and his unflagging confidence in himself and his men.

On the morning of April 7 Grant’s predictions rang true. The fighting was heavy, but the Confederates lost all the ground they had gained the first day. Beauregard, who realized that he had been outfought, ordered a general retreat to Corinth.

It had been a close-fought battle. Johnston, who gave his life for the Confederate cause that day, had successfully concentrated his far-flung forces and had pulled off one of the most stunning surprise attacks of the war. The South had good reason to weep, for Johnston was a truly gifted commander. As for Grant, he had risen to the occasion; however, the Union victory was by no means an unalloyed triumph. Grant had grossly underestimated the offensive spirit of Johnston’s army, and it had almost led to his undoing.

The clash at Pittsburg Landing was the bloodiest battle up to that time, with the Union suffering 13,000 casualties and the Confederates losing 11,000 men. It was a sobering clash for both sides given that more men had been killed in the battle than the Revolutionary War, War of 1812, and Mexican-American War combined. Sadly, it was a foretaste of even greater, albeit tragically necessary, butchery to come.

Shiloh was a crucial milestone for both Grant and the Northern cause. The hard-won victory opened the way for the eventual fall of Vicksburg the following year and Union control of the Mississippi River. The Confederacy would be cut in half. When that occurred, Lincoln observed. the “Father of waters again goes unvexed to the sea.”