By David Ison

Imagine a time when human knowledge of elephants was not widespread. Just think how threatening these large animals would be coming over a hillside or out of a mist during battle. In addition to their odd and threatening appearance, the sounds the elephants made would have been just as frightening. It is not difficult to appreciate how war elephants struck terror in those who had never seen them before.

Yet the role of elephants went far beyond mental terrorism in war. They provided an excellent means of transportation and could be used to move heavy equipment and supplies over large distances. They were also their own form of cavalry, able to charge at tremendous speed. Their sheer size made war elephants all but unstoppable. Many armies used elephants to charge the opposition, particularly the enemy’s cavalry, crushing all who got in the way. On some occasions, the elephants’ tusks were mounted with spikes to inflict even more damage. This type of outfit was particularly useful in elephant-on-elephant combat. The sturdy elephants often carried howdahs, or canopied saddles, on their backs, complete with archers and javelin throwers. Larger elephants were outfitted with tower-like devices protecting occupants from ground-level attack and providing an excellent battlefield vantage point.

Ancient Warfare and the World’s First War Elephants

The first use of elephants by humans began about 4,000 years ago in India. Elephants were initially used for agricultural purposes. They could literally rip trees out of the ground, clearing wide areas for farming and construction. Because they quickly demonstrated their trainability as well as their strength, it was only a matter of time before the giant animals were incorporated into military use. According to Sanskrit sources, this transition took place around 1100 bc. (Learn all about the implements and tactics of ancient warfare inside the pages of Military Heritage magazine.)

Many assume that elephants conscripted for military use were domesticated. This is not so. For several reasons (financial considerations probably being the foremost), elephants were rarely bred in captivity. The overwhelming majority of war elephants, in fact, were captured and trained. Male elephants, being inherently aggressive, were used for combat. Female elephants tended to retreat when facing a charging male—obviously not something that was desirable on the battlefield.

There were many traditional ways to trap elephants. One ingenious method employed by inhabitants of the Indus Valley was to dig a circular ditch, creating a dirt island. Across this waterless moat would be a bridge to the raised center. On the central island, captors would place one or more female elephants. Males would be drawn by their scent and sound. Once the male reached the females in the center, the bridge would be removed to trap it inside.

Elephants are very intelligent and take well to training. But no matter how well prepared and disciplined they are, elephants are still wild at heart. This posed problems to their use in combat. On more than one occasion, elephants panicked and trampled friendly soldiers during confrontations. Because of this, it was not uncommon for the mahout, or driver, of the elephant to carry a device such as a chisel or sword to sever the animal’s spinal cord if it began to act contrary to what was desired.

Several types of elephants were used by militaries throughout the eastern hemisphere. For the most part, the type of elephants employed was related to geography—those most readily available were the ones most often used. Although there has been much debate about the specific types of war elephants, DNA evidence now shows that two distinct species of African elephants were used, the forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis) and the savannah, or bush, elephant (Loxodonta africana). An additional species (some argue it is a subspecies) of African elephant, the North African (Loxodonta pharaoensis), was used for a time, but it became extinct around the second century ad. The Asian or Indian elephant (Elephas maximus) was also used quite a bit for military purposes.

The most obvious distinction among elephant species is size. The typical African savannah elephant measures 10 feet tall, but some have been recorded as tall as 13 feet. Forest elephants, however, measure around 8 feet. Northern African elephants are slightly smaller than the forest types. Asian elephants grow to between 7 and 12 feet tall, although overall they tend to be smaller than the African savannah elephant. The most distinguishing feature is ear size, with the savannah elephant having the largest set. While size was certainly an influence in conflicts, bigger did not always mean better. The outcome of conflicts had more to do with strategy than with elephant training and handling.

War Elephants of Mesopotamia

While there were many small-scale uses of war elephants following their implementation around 1100 bc, the first well-known conflict involving Europeans was at Gaugamela in October 331 bc. This battle, which took place in northern Iraq, pitted Alexander the Great against the Persian leader Darius III. Along with 200,000 Persian troops, 15 Asian war elephants joined the ranks to overawe the opposing troops. There is no doubt that Alexander’s troops must have been, at least initially, daunted by these strange, large animals. Even with these mighty beasts at hand, however, Darius could not overcome Alexander’s troops and tactics. Babylon was captured and the concept of war elephants became well known west of Persia.

In 326 bc, Alexander moved to invade Punjab, India. Parvataha, also known as King Porus, met the invasion with resistance at the Hydaspes River. In the ensuing battle, Alexander faced more than 100 war elephants (one source reports double that number) with archers and javelin throwers on their backs. Because Alexander had encountered the unique animals previously, he and his troops were not quite so panic-stricken. Alexander ordered his javelin throwers to attack the gray ogres. This set the elephants in disarray, eventually leading to the trampling of many of Porus’s own troops. Alexander then surrounded and defeated the Indian army. After doing so, he captured 80 elephants that he would integrate into his army.

When Alexander died in 323 bc, his kingdom was divided, along with its elephant assets. Left without these strategic animals was Ptolemy, who occupied Egypt. Ptolemy invaded Syria with approximately 22,000 men but was met by 43 war elephants and 18,000 troops led by Demetrius, a descendant of Antigonus, who had retained control over Alexander’s Anatolia assets. In the ensuing Battle of Gaza (312 bc), Ptolemy was successful in holding off Demetrius and captured all the elephants on the field.

Following Gaza, a coalition of enemies gathered to oppose Antigonus and his son. The so-called Antigonids, with 80,000 soldiers and 75 war elephants, faced off against a coalition force of 60,000 and 400 war elephants at Ipsus in 301 bc. The Antigonid forces were eventually overwhelmed by their opposition. Seleucid elephants apparently had a big influence in the victory by isolating part of the Antigonid army from the rest.

The Elephants of Pyrrhus and Ptolemy IV

The next major skirmish involving elephants dragged Rome into the exploitation of the huge animals. In 280 bc, the Pyrrhic Wars brought the Battle of Heraclea. Pyrrhus of Epirus, called to assist fellow Greeks under the thumb of Roman rule, invaded the south end of the Italian boot. Pyrrhus brought with him a number of war elephants. It is rumored he tricked the beasts into boarding rafts to cross the Adriatic Sea by camouflaging the boats so that the elephants could not see the water.

The Roman army had never seen the strange animals, and soldiers were rightfully petrified, the cavalry particularly so. Roman horses, which had never met elephants, were easily scared by the scent, sounds, and appearance of the opposition’s eccentric weapon. The Greek historian Plutarch described the scene: “The elephants more particularly began to distress the Romans, whose horses, before they came near, not enduring them, went back with their riders.” Along with the Greek phalanx, the elephants defeated the Romans in a long, costly battle.

But the Romans were always quick to learn from their mistakes and almost immediately devised methods to resourcefully deal with war elephants. A year later, at the Battle of Asculum, Roman legions used approximately 300 anti-elephant devices, from fire pots to ox-drawn chariots outfitted with spikes, to counter Pyrrhus’s 20 war elephants. While Pyrrhus claimed a very thin margin of victory, it gave the Roman army tremendous experience and confidence in how to counter elephant forces effectively.

In 217 bc, Antiochus III, leader of the Seleucids, and Ptolemy IV met at the battle of Raphia in Palestine. Antiochus III had 62,000 infantry, 6,000 cavalry, and 102 war elephants (the larger Asian version). Ptolemy IV led 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry, and 73 elephants (the smaller African forest type). Even with the size disadvantage among elephants, Ptolemy IV defeated the Seleucids.

Rome Against Elephants

Probably the most famous use of elephants was that of the Carthaginian general, Hannibal. During the Second Punic War, Hannibal gathered an army of varied cultural backgrounds, which also included 37 elephants of the North African type to travel from Spain, through Gaul, over the Alps, and into northern Italy. Some of the elephants could not make the arduous journey, leaving Hannibal with a motley, unimpressive force. By 202 bc, Roman general Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus defeated Hannibal’s forces at the decisive Battle of Zama. Scipio Africanus simply ordered his troops to move out of the way of the charging elephants, which could not change direction easily due to their tremendous momentum and massive bulk.

The Romans always seized an opportunity. Fresh off the defeat of Hannibal and upon learning of the downfall of the Seleucids, Roman legions invaded Turkey. This movement culminated at the Battle of Magnesia in 190 bc. Antiochus III still had at his disposal many of his war elephants, which he incorporated into his plans. However, the Romans were already wise to the elephants and planned accordingly. The Roman cavalry charged the elephants, sending them fleeing in terror. In the end, Antiochus lost 53,000 men and caved in to Roman might.

Even Julius Caesar used elephants. In 46 bc, in the midst of the Roman civil wars, Caesar took on rebellious forces led by Marcus Porcius Cato, the Younger, and Quintus Caecillius Metellus Scipio at Thapsus. By this time, war elephants were considered far from innovative by Roman forces—they’d had plenty of experience fighting them. The familiarity served them well. Quintus Scipio’s 120 elephants were targeted by Caesar’s archers, slingers, and axe-men. The animals were terrified by the Roman use of arrows and projectiles as well as the axes to their legs. The enemy forces were easily defeated by the Roman Fifth Legion. But because of their noble efforts, the elephant was adopted as the legion’s new symbol, trumping the traditional icon of a bull.

Why Were War Elephants No Longer Used?

As time drew on, the use of war elephants in Europe and Africa declined. One reason for the decline may have been related to the decimation of the Northern African elephant population by ivory dealers harvesting the animals for their tusks. But the European use of elephants did not completely disappear. Charlemagne took elephants with him to fight the Danes in ad 804, and Frederick II used an elephant he captured during the Crusades to besiege Cremona in ad 1214.

The use of war elephants in Asia continued with more regularity. In ad 1009, the Ghaznavid conquests brought on the Battle of Peshawar in northwestern Pakistan. Mahmud of Ghazni ganged up on an alliance of Hindu princes led by Anangpal. The Hindu princes had massed a large elephant force, but as was often the case with large numbers of the animals, their performance was unpredictable. Mahmud was able to alarm the animals, sending them into frenzy and crushing the Hindu forces. After the end of the battle, Mahmud added captured elephants to his army.

War elephants were used quite a bit in other parts of Asia as well. During the Khmer-Champa Wars in Cambodia in ad 1177, both sides used the animals. The weaponry used from the vantage point of elephant saddles grew more sophisticated and innovative. These novel tactics were used with gusto at the Battle of Panipat, near Delhi, India, in ad 1399. There, Timur, a Mongol conqueror, challenged the sultan of Delhi. The sultan had at his disposal a number of war elephants. From these imposing brutes, the sultan’s forces launched liquid-filled incendiary weapons. Also, metal rockets were fired at the oncoming forces. But Timur’s troops did not budge. Soon Timur claimed victory.

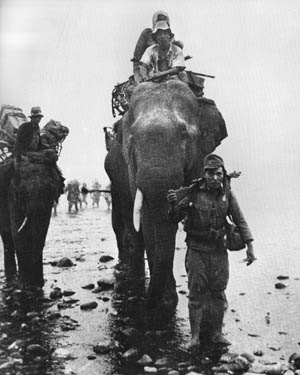

Around the 15th century, gunpowder became prevalent in war. With cannons and guns, the elephant lost its offensive efficacy. Nevertheless, the elephant has continued its military service through modern times, still a viable means of transportation in a variety of settings. Elephants were used frequently during conflicts between Burma and Thailand through the end of the eighteenth century. In World War I, elephants were used to move heavy artillery. The Japanese used elephants quite a bit in World War II to carry supplies deep into jungles, surprising allied forces. The British eventually used elephants to build runways and roads in Asia in an effort to challenge the Axis forces. During the Vietnam War, the Viet Cong used elephants to assist in the transport of supplies to the south. Even today, elephants are being used by Burmese rebels in their efforts to topple the government.

Weaknesses of the Living Weapon

As with any weapon, much effort was put forth to counter any advantage war elephants gave the opposition. Over the years, many imaginative plans were formulated to deal with elephants. Timur ordered straw to be placed on the backs of camels and lit on fire. The blazing camels then charged the elephants, which immediately became uncontrollable. It was also discovered that elephants had a particular dislike of pigs, particularly their squeal. This fact was mentioned in text by Roman historian Pliny: “Elephants are scared by the smallest squeal of a pig.” Reportedly, pigs slathered with oil were set afire then were sent in the direction of the elephants, which resulted in a stampede of the larger animals.

It did not take long for strategists to figure out that without a mahout, war elephants were useless. Thus, the mahouts were specially targeted by archers and javelin throwers. Another tactic was to take advantage of an elephant’s weak spot, its foot pad. Spiked devices (caltrops) or barbed planks were commonly thrown in the path of the animals to make them lame. Also, since elephants often picked up troops with their trunks, some soldiers were outfitted with special armor to damage the trunk if the elephant attacked. Lastly, axmen commonly targeted elephants’ legs to disable them. Unfortunately, for the attackers, the thickness of the elephant’s skin made maiming the creature a difficult task. In an effort to protect the elephants’ vulnerabilities, they were commonly outfitted with impressive armor.

Versatility On and Off the Battlefield

On occasion, elephants were used for military purposes off the battlefield. One such use was to execute enemies: an enraged elephant would be unleashed on those sentenced to be annihilated. Elephants were also used as siege weapons. There are several accounts of elephants using their heads and tusks to batter fortifications until they faltered. The animals were also used to ford rivers. They could be used as “bridges” or simply to block the current to allow troops to cross a rapid.

While the overall success of the elephant as a war weapon is debatable—they could be as much a hindrance as a help—their brute force as a tactical weapon cannot be argued. Their ability to move heavy items and to assist with sieges and transportation certainly made them worthwhile, even if they were never actually consulted about their own willingness to take part in the brutal business of human war.

Nice overview. Might I suggest a similar article on the use of camels in warfare as their utilization followed a similar arc.

Interesting story, i enjoyed it

There was a time about 1400 years ago where an army of elephants was destroyed by birds. The swarm of birds were picking and pecking the elephants aggressively and ended up causing the elephants to fall into lava rocks. This is a story passed down from about 9 generations ago in Jerusalem. However they dont know where exactly this took place. Could have been Petra Jordan or somewhere in the region.

Look into it. See what you can find. Peace.