By Tim Miller

At the age of 50, John of Bohemia was already old for a warrior and completely blind. He not only was the Count of Luxembourg and King of Bohemia, but also claimant to the thrones of Poland and Hungary. On August 26, 1346, he found himself just south of Calais in northern France, fighting for the French against the English near the village of Crécy. Although unable to see what was occurring, he was able to hear the rout of the front line of Genoese crossbowman and the charge and repulse of the first wave of French cavalry.

He asked two of his barons how bad the situation was, and they told him that the French forces were being cut to pieces. “You are my men, my companions and friends in this journey,” he said. “I ask that you bring me forward, that I may strike one stroke with my sword.” At the doubts of a few of them, John insisted that they join the fight. “Let us go forward and die with honor,” he said. Seeing no way to object further, the men are said to have “lowered their voices like lambs” and assented, according to an anonymous Roman chronicler. They then tied the bridles of their horses together to guide him.

He would never see the last field he fought upon or wash his hands in the nearby stream or even know from the evidence of his senses that the day was ending just as his life was ending, too. “Lead me into the thick of the fray and God be with us,” he said. Once there, the wings of the English army closed around him and his men, and the blind man was quickly driven from his horse. Soon after the French knight who carried John’s banner also fell, and John himself was trampled to death by the two horses to which his own was attached. John’s death was mourned on both sides. Prince Edward of Wales, whose division had slain John of Bohemia, later adopted his crest and motto.

The Battle of Crécy was the first large-scale land battle in the Hundred Years War. The conflict began as a typical drama of royal succession. Philip IV, king of France, died in 1314 with what he might have imagined was a continued lock on the French throne for the Capetian dynasty because he had three sons. And indeed all of them did succeed him, but by 1328 they were all dead, too. Louis X had died at 26, Philip V at 29, and Charles IV at 33. None of them left a male heir.

Philip IV’s daughter, Isabella, had married the king of England in 1308, making her son, later king Edward III, closest in line to the French throne. In swooped Philip of Valois, and with the French barons and prelates on his side, they invoked a clause in the Salic law that stated that women could not inherit landed property. It was the first time the French crown had invoked the law that had been instituted eight centuries earlier by Frankish King Clovis.

Not surprisingly, this clause was extrapolated to cover kingship; after all, if a woman could not inherit property, how could she inherit a kingship that could never be hers, let alone pass that claim to her children? No doubt this interpretation had something to do with an English king being so close to the French throne, and it easily won support. The French crown declared that the transmission of kingship could only pass through the patrilineal line, making Philip of Valois (Philip VI) the new French king. The English contested the claim, insisting that Edward III should be made king over the French by right of his mother Isabella.

History is never quite as easy as arcane or convenient interpretations of law, though. At the time of Philip’s accession, Edward III had been on the English throne only for a year. Edward was crowned king in 1327 when he was 15. Even more dramatically, he had only come to the throne after his mother and her lover, with the support of French King Charles IV, had deposed, imprisoned, and likely murdered his father, Edward II. Following a decade in which his half-brother and first cousin had also been executed, no one would have expected that Edward would reign for the next half century. Yet he showed his willfulness almost immediately. His mother and her lover were made the fools if they assumed the young king would be easy to control. In 1330 he forced his mother into retirement, while her lover was tried and executed for various crimes. In the middle of this, Edward’s rightful claim to the throne of France was taken from him by a technicality, and yet he had the temerity in 1329 to travel to the Cathedral of Amiens and, expected to accept Philip’s claim, did so in such a vague way as to ensure future disputes.

Edward also immediately renewed England’s continual wars with Scotland, and in 1333 won a victory at Halidon Hill, installing an English-backed king. This prompted the expected response from France, which supported a different monarch for Scotland. Through the Auld Alliance, France frequently sent aid to Scotland in its wars against England and vice-versa. Although the French requested Scottish assistance at Crécy, the Scots were unable to provide it.

Two more matters exacerbated the dispute. The first involved an exile from the French court, Robert of Artois, who escaped to England and whom Edward III refused to extradite. The second concerned the area of Gascony in southwest France, which had long belonged to the English but only on the condition of their recognition of the the French crown. As a show of disapproval over England’s treatment of Scotland and its refusal to extradite Robert of Artois, Philip annexed Gascony in 1337 and invaded it the following year, prompting Edward to declare himself the rightful king of France. Artois, by then a trusted adviser of Edward’s, seems to have egged the king on in his own way, reputedly placing a heron, the symbol of cowardice, before him at a banquet.

But Edward must have soon realized that Philip felt hemmed in by his moves. While France was clearly more powerful and boasted a larger population, England was more united than France. For Philip, it was unlikely that the population of Gascony would quietly become French subjects, no matter how the French tried to either force them or foment rebellion there. Like their neighbors the Basques of northern Spain, the Gascons had their own culture and customs and even their own language. They preferred the English to the French in part because they were allowed more autonomy under the English. Flanders also was largely autonomous. When Edward, in response to Philip’s actions, halted the export of English wool and invited manufacturers from the Low Countries to set up shop in England, the threat to the remaining Flemish merchants was a real one. As such, Edward’s claim was said to have the support of everyone from the sheep farmers on up. This included the authorities of Ghent, Ypres, and Bruges, all of whom declared Edward the rightful French king.

As English rulers or enemies all quickly realize, though, any expedition going either way across the English Channel becomes an immensely expensive logistical endeavor. While Edward’s forces did defeat the French fleet off the Flemish port city of Sluys in 1340, in 1337 and 1339 full-scale invasions of the Continent had faltered over lack of money, and another would not be attempted until 1346. There was, as yet, nothing like a dependable military industrial complex for either country to rely upon, and the finances of such an invasion were so precarious that Edward’s later inability to pay back a loan received from the famous Bardi bank of Florence led to its collapse. Even the money earned from England’s wool trade, which at one point was being diverted for the war effort, was not enough. Meanwhile, Philip’s subjects refused to pay any more taxes during the brief truces of 1340, 1343, and 1345, stubbornly declaring they would pay no more taxes unless there was an actual invasion.

By early 1346, though, Edward had his money and began gathering his supplies and forces. With no permanent navy, the 700 ships used in the invasion belonged to fishers and traders knowing they would be paid well by the king. They began gathering at Portsmouth near the end of April and for the next two months supplies were assembled for the invasion.

Unlike the campaigns in Scotland, which could easily be replenished by land, there was no such luxury awaiting the English army in France, both thanks to the unpredictable weather in the English Channel and the likely hostile French population.

The amount of equipment, ammunition, and food needed to support the English army on campaign was staggering. To outfit the long-bowmen, for example, more than 132,000 arrows and 5,500 sheaves were ordered, and the work to produce them was spread throughout the country. Once at Portsmouth, approximately 60 carts alone were needed to transport these supplies to the Continent and beyond. English archers, mounted knights, and men-at- arms were responsible for their own swords, lances, and knives, the production of new innovations like early cannons and 12-barrel ribalds (operated by two or three men and firing lead shot) were the responsibility of the armorers at the Tower of London, which also served as a collection point for supplies as they came in from throughout the country.

The soldiers in battle required a wide array of leather and iron protection. The knights wore various types of helmets, including snout- faced bascinets. They were clad primarily in plate armor and wore surcoats over their armor. As for the foot soldiers, they sported kettle hats and wore quilted gambesons or brigandines reinforced with metal strips to protect their upper bodies.

A medieval army on the move was less a matter of organized lines of men and matériel and more like a merchant caravan. Along with soldiers of all stripes there were also carpenters and engineers who would prove invaluable in navigating a French countryside whose bridges would end up destroyed or sabotaged ahead of their arrival. There were also those responsible for the army’s food supply. It was assumed that the French would take to burning their fields and slaughtering their animals rather than have them satisfy the hunger of the invading army, and so in the months leading up to the invasion royal purveyancers scoured England and were able to buy huge supplies of food at much cheaper prices than usual. Flour, oats, pork, peas, and beans were packed into huge barrels. As with the thousands of carts needed simply to roll its more valuable product along, an enterprising person may well have earned a fortune in producing barrels or in coordinating the transportation of them to Portsmouth. Fresh meat was supplied by the small herd that accompanied the army, but since no meat was eaten on Fridays, there was also wide sampling of fish as well as 130,000 gallons

of wine.

In addition, the English transported approximately 10,000 horses—belonging to

knights, men-at-arms, or mounted archers, or those used for transport—across the English Channel. This alone required a special talent, and upon landing the horses had to be rested for a few days to relieve the stiffness from standing for a more than a week.

By the 1330s England was able to field a fairly regular and reliable volunteer army that was well paid and professionally trained. Edward III’s army at Crécy was composed of 12,000 men: 7,000 English and Welsh archers, 2,700 men-at-arms, and 2,300 Welsh spearmen. As for payment, a common soldier received two to three times that of a peasant laborer. Many aristocrats also raised armies from their own tenants, households, or localities, with the young men from entire towns or villages filling out proto-regiments that would have a long pedigree in the history of European warfare. Where volunteer numbers were scarce, convicts were pardoned in exchange for their service. The rolls were also filled with archers and spearmen from Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland. In contrast to the handful of languages that hampered the communications of the French army, aside from some German mercenaries among the cavalry and men-at-arms, Edward’s army had no language barrier of any kind. What is more, many of the men had served together before.

The French army numbered 30,000, comprising 6,000 Genoese cross-bowmen, 10,000 mounted men-at-arms, and 14,000 conscripted feudal infantry. The French were still caught in the chivalric ideal where mounted knights and men-at-arms made the difference in a fight, and so they refused to believe that proper tactical implementation of their infantry could mean much, let alone turn the tide. If the French were caught off guard by the final location of the invasion, this was in part because the English were as well.

Amazingly, in a letter on July 6, after a few days of bad weather that made crossing impossible, Edward III remarked that when they finally did set out they would go wherever the wind took them. The major English ports of London, Dover, Winchelsea, and Sandwich had been closed for the two weeks before and one week after the invasion to keep news of it from spread- ing, but it is hard not to imagine that such action actually clued the French in to what was happening, since earlier in the year they had called upon a Genoese fleet to protect the French coast. But by early July the Genoese had only reached Lisbon and, the actual English landing at the Cherbourg peninsula was more than 100 miles away from the Seine estuary where the French were expecting the invasion. The Cherbourg peninsula had only a local defense force at best; while there were approximately 300 Genoese bowmen there, they refused to fight because they had not yet been paid.

And so, with very little opposition, Edward’s army landed at St. Vaast la Hogue on July 12. His troops spent the next five days unloading supplies and raiding the surrounding countryside. By the time they were done, the English had left a 21-mile-long swath of destruction behind them. Indeed, the English army never had to camp out in the open during the 39 nights they spent on the campaign because they drove the locals out of whatever town, village, or city they came to. Once they decided to move on, the place was almost completely destroyed. At the city of Barfleur, for example, some of its leading citizens were taken hostage until a ransom was paid, after which the town was destroyed and its riches pillaged.

Edward then separated his men into three divisions. King Edward led the main body, his 16- year-old son led the vanguard, and William de Bohun, the Earl of Northampton, led the rear guard. At that point, Edward took steps to protect French towns and property from any further destruction. “No house or manor was to be burnt, no church or holy place sacked, and no old people, children or women in the kingdom of France were to be harmed or molested,” read King Edward’s proclamation. It fell on deaf ears, though, as the English troops proceeded to burn every town on their route of march.

On July 20 they sacked the town of Carentan, and since Edward was still at this stage of the campaign envisioning holding the territory he conquered, he left a garrison to oversee the town and accepted the local commanders’ surrender. Shortly afterward Edward’s army ransacked the town, killing more than 1,000 people before he left. The French retook the town, killed the English garrison and sent their commanders to Paris to be executed for treason. But even Carentan was nothing compared to the destruction of Caen.

From the start of the campaign Edward had been reluctant to lay siege to any town as large as Caen, but the reality on the ground proved that to let it alone would be disastrous. It also helped that the three wings of the army had been reunited just before approaching the city, with 200 of the ships following them inland via the River Orne. When Edward sent a monk to Caen to offer terms of its peaceful surrender, the powerful bishop of Bayeux, head of the garrison sta- tioned at Caen’s castle, had the monk arrested. Wasting no time, the next morning Edward sent in his men, and by day’s end more than 2,500 had been killed. Among the slain were the townspeople who had improvised barriers to help the French forces, as well as a number of French noblemen who, if the English had been following expectations, should have been taken prisoner and ransomed. But loot was in no short supply at Caen, and news of the riches taken there reverberated even louder than the city’s destruction.

“The woman was of no account who did not possess something from the spoils of Caen and Calais and the other cities overseas in the form of clothing, furs, quilts, and utensils,” wrote 16th-century English statesman Thomas Walsingham. Scholars in the 18th century could apparently chart the prominence of certain families via the wealth the spoils of Caen had brought them. Indeed, the Crécy campaign can be seen as a turning point when loot and plunder of this kind became as expected a part of military service as regular payment or grants of land.

The city of Bayeux, whose bishop had led the resistance in Caen, saw the writing on the wall and surrendered quickly. Somehow still imagining that he might keep an English force on French soil after hostilities ended, Edward left another garrison in Bayeux and continued on. By the end of the month that garrison had also been murdered and the town retaken.

Edward met twice with a delegation of cardinals sent by the Avignon Pope Clement VI, who hoped to broker a peace deal, the second time with a marriage alliance between the houses of Valois and Plantagenet. Nothing positive came of either meeting, although a humorous episode unfolded when a handful of Welsh horsemen stole the cardinals’ mounts. By August 4, Edward’s allies in Flanders were now in French territory and attacking south of Calais so that Philip actually was fighting on three fronts: Artois, Aquitaine, and Normandy.

The next 20 days saw inconclusive skirmishing. It is difficult to discern Edward’s true intentions at that point. Although he clearly intended to conduct a chevauchee that would challenge King Philip’s authority and demonstrate in stark terms his inability to protect the people of Normandy, it is less clear whether he intended to provoke a pitched battle. He had every confidence, though, that his army could repulse a French attack.

On his march to Flanders, Edward avoided the French army at Rouen and headed for Elbeuf where he found that the French had destroyed the bridges over the Seine River. Following the river south, with Philip’s army across the river, the English army was again hampered by repairing a bridge over the Seine at Poissy. Meanwhile, the French withdrew temporarily to Paris. While searching for one of these crossing points, French soldiers on the other bank were said to have bared their back- sides to the frustrated English.

Once Edward was finally across the Seine, he skirted Paris entirely in a dash north to meet up with his Flemish allies. Along the way he encountered more and more garrisoned towns and local Frenchmen ready for a fight, haphazard militias and trained knights among them. While these forces posed no immediate threat to the English army, they were persistent and annoying enough to cause delay in its trek north. At least both armies got a rest on August 15, the feast of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, when military maneuvers ceased altogether.

By August 22 Edward’s army reached the Somme River. The French had destroyed the

bridges over the lower Somme, thus impeding Edward’s attempt to reach his Flemish allies. When Edward learned of a tidal causeway called the Blanchetaque that could be crossed when the tide was out, his men made quick work of it, crossing in less than an hour, easily beating off the French force sent to harass them. “When we came to the river Somme, we found the bridges broken, so we went towards St. Valery to cross at a ford where the sea ebbs and flows,” wrote King Edward. “By God’s grace a thousand men crossed abreast where before this barely three or four used to cross, and so we and all our army crossed safely in an hour and a half.” Shortly thereafter the English arrived at the forest of Crécy and the village of the same name. They were aware that the French army was near. Edward was famil- iar with the terrain because he had been in Crécy as recently as 1329—the area in which it lay, Ponthieu, had been an English possession until 1338. The king knew a good piece of ground when he saw one. Knowing that battle was now unavoidable, he waited for the French to arrive.

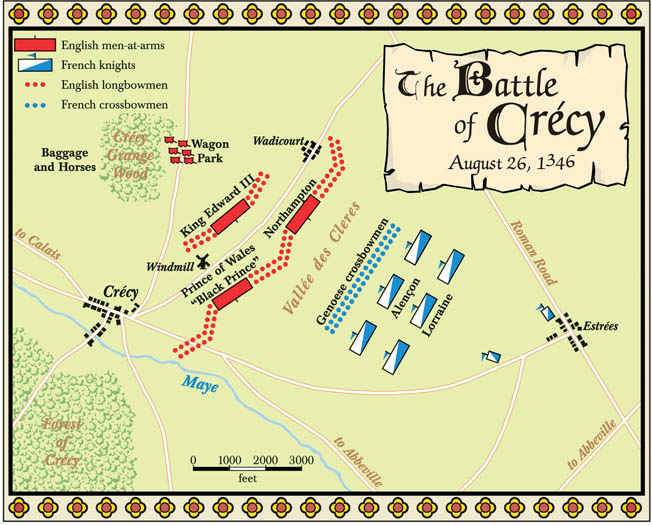

On the morning of August 26, the English army was arrayed north of Crécy on a slight rise in the landscape. Its left flank stretched all the way to the village of Wadicourt, while the right edged close to Crécy and the River Maye, protected by the nearby forest and swamp. As a handful of contemporary sources describe, the extreme right flank was protected by a defensive barrier of carts.

King Edward ordered all of his men-at-arms to dismount. The grooms took the horses to the rear where they were protected in a makeshift corral formed by the baggage carts. Prince Edward commanded the right wing under the watchful eye of Thomas de Beauchamp, the Earl of Warwick, and Northampton commanded the left wing. King Edward commanded the reserve, which deployed behind the right wing. The dismounted men-at-arms deployed in the center of each of the three formations with longbowmen on both flanks. Positioning the men-at-arms in the center afforded them the flexibility to reinforce either flank if necessary.

Always ready to learn from their defeats, the English also took a page from the Scottish victory over them at Bannockburn in 1314 and dug dozens of postholes in front of their lines to trip the French horses. At mid-afternoon, Edward III rode a conspicuous white horse among his ranks and encouraged his men to defend his right to the French throne.

The French army stumbled upon the English almost by accident. The lead elements of the French vanguard sighted the English army at noon. The French were strung out over 12 miles of road. Philip VI was prepared for a fight, but he had not decided whether to attack right away before all of his troops were present or to postpone his attack for the following day. His nobles, however, were itching for a fight. They overrode their king’s impulse to rest for the evening.

Indeed, the cocky French nobles already were discussing how they would divvy up the high-value English prisoners they knew they would find at Crécy and calculating the ransom each was likely to draw.

As the French army left Abbeville for Crécy, suddenly the force, which had harassed Edward III for the past month, became a motley, undisciplined crew. “This disorder was entirely caused by pride, every man wishing to surpass his neighbor,” wrote chronicler Jean Froissart. Even when one mentions that Philip was the only monarch to actually enter the fight, given that Edward III directed his lines from atop a nearby windmill, the chroniclers tell us this only happened because Philip was suspicious of his nobles, as well as the foreigners in his ranks.

With that said, it is ironic that Philip would put the Genoese crossbowmen in the first line of battle together with blind King John of Bohemia and 300 mounted men-at-arms. The second line of battle consisted of the bulk of the French heavy cavalry led by Charles II, the Duke of Alençon, who was Philip’s younger brother.

With no time to rest or wait for the remaining line and baggage train to arrive, the Genoese crossbowman advanced at 5 PM. They apparently were jostled into view of the English lines by the eager French cavalry behind them. Tired from the march, the Genoese crossbowmen also complained at having to advance without their pavises and reserves of ammunition, which were still far back in the baggage train with the rest of the foot soldiers.

To make matters worse, the crossbowmen’s advance also was marked by a sudden rain shower. When the clouds passed and the sun came out, it appeared behind the backs of the English line and shone directly into the faces of the Genoese. With the effectiveness of their crossbows now limited from the downpour, the Genoese halted a handful of times before finally unleashing a volley at the English.

In response, the much more powerful longbows, which their users had kept covered during the storm, filled the sky, as did the strange new sound of cannons. If the latter were still ineffective as weaponry, they shocked the French side simply with their sound, not to mention the confusion of their smoke. Amid such din it was unlikely the Genoese would have been able to hear the trumpets or drums that might direct them elsewhere or see the banners that would do the same. The arrows from the longbowmen continued without end. A good bowman could get off 15 shots per minute, a rate three times as fast as a crossbowman. The Genoese wasted no time. They turned to run and almost immediately were trampled by the advancing French cavalry of the second line that rode toward the English right flank.

The Genoese were upset at having not been paid and chose this moment for treachery, according to an anonymous Roman chronicler, who wrote, “These men are not firing their crossbows, and if they do fire them they are using wooden shafts without iron tips. Let the Genoese die.” Another contemporary account echoes the claim of treachery. “The French knights and men at arms, seeing them flee, thought they had been betrayed; they themselves killed them, and few of them escaped,” wrote chronicler Giovanni Villani. The rash destruction of the Genoese forces backfired almost immediately, and the French cavalry, which was attacking uphill, quickly became bogged down amid their fallen bodies all as they continued to come under fire from the English longbowmen. “The arrows of the English were directed with such marvelous skill at the horsemen that their mounts refused to advance a step,” wrote chronicler Jean le Bel.

Some horses leapt backwards stung to madness, some reared hideously, some turned their rear quarters towards the enemy, others merely let themselves fall to the ground, and their riders could do nothing about it.” In other words, all the cavalry armor in the world could not protect their horses from injury or confusion. Against such an onslaught the traditional use of the cavalry charge was essentially rendered useless, and the Duke of Alençon was killed in the fighting as his own men retreated, only to regroup and attempt another charge. If it is true that a medieval cavalry advance was not likely any faster than a trot, it is not hard to imagine how slow this advance, repulse, and advance truly became. Meanwhile, those few who reached the English lines were beaten back by their men-at-arms and their own cav- alry as the longbowmen melted into the back- ground, having done their job. The French cav- alry launched 15 separate charges, all of which were repulsed. As the battle progressed, the French assaults became increasingly confused. Philip apparently attempted to lead a final charge, but John of Hainault grabbed his reigns and led him to safety.

Amid the melee of French cavalry charges, which mainly focused on Prince Edward’s division on the army’s right, the king’s son himself was unhorsed and put in mortal danger. Upon hearing the news of his son’s predicament, Edward is believed to have told the messenger that reinforcements were not necessary. The king supposedly did this so that young Edward would have an opportunity to “earn his spurs.” This may be a bit of the victor’s propaganda, or even an attempt by the English to picture war as it had once been, more a matter of individual and aristocratic prowess than a more capable use of lowly infantry.

Yet the collapse of the French forces, and the fact that the blind King of Bohemia’s suicidal charge remained one of the more memorable moments from their side, shows how dated such a view of warfare had become. As has been said thousands of times already, Crécy represented the triumph of the longbow and therefore of the everyday soldiers. It only took slightly more than four hours to make this point. The stragglers from the French line, still arriving at that late hour, were all cut down, while Philip VI eventually withdrew with what was left of his forces and was not pursued.

Before the battle, both monarchs had declared that no prisoners were to be taken and

no quarter given to the wounded or captured. But this was understood to refer to those who were not nobles since the capture and ransom of a noble was as much an opportunity for a paycheck as actual plunder. The infantry on both sides of a battle fought so ferociously and in such an unchivalric manner because they were worth nothing in exchange and quite literally fought for their lives.

English soldiers walked among the French wounded and killed them all, regardless of station, including approximately 1,500 nobles. A handful were separated out for proper burial, but most were placed in a mass grave that later took on the name Valees des Clercs. Meanwhile, the local monks buried the English dead in the corner of a field that was never ploughed again.

The Battle of Crécy was unique in the annals of the Hundred Years War in that it was the only time that the king of England and king of France would face each other on the field of battle. The battle proved that the English army was capable of defeating a first-rate power on the battlefield. Previously, the English had only bested the Welsh and Scots. But in the wake of Edward’s victory over the French in the Battle of Crécy, the English army’s standing in the eyes of feudal Europe rose considerably. The achievement was particularly impressive considering that the population of England was approximately six million compared to France’s slightly more than 12 million. The larger population of France meant that it had more manpower and greater revenue than England.

The upshot of the victory was that Edward was able to march to the port of Calais and besiege its French garrison. This he was able to do without fear of attack by Philip VI, who although he contemplated trying to lift the siege ultimately decided against risking his army a second time. The siege began on September 4, 1346, and ended with the surrender of the French garrison on August 3, 1347. The successful siege gave Edward and his successors a reliable point of entry into north-eastern France, meaning that they did not have to rely on their Low Country allies for a port to debark their troops and supplies.

The French House of Valois remains on the French throne for the next two centuries, while the English House of Plantagenet was succeeded a century later by the Tudors, and the security of neither monarchy ever seems to have really been at threat. If anything, the war succeeded in solidifying a separate French and English identity, an event that in its own way was no more a recipe for peace than a forced attempt at union.

England’s supposed advantage in recruiting troops led to famous but ultimately inconclusive victories at Poitiers and Agincourt, but in the end England was left with no continental possessions beyond Calais, which itself would fall to a resurgent France in 1558.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments