By Susan Zimmerman

The 83rd U.S. Infantry Division had been mobilized for World War I in September 1917. Its unit patch was a downward-pointing black triangle with the letters O-H-I-O stitched as an abstract gold monogram in the center. As the letters suggest, it had its origins as a mostly Ohio unit, although after the outbreak of World War II, there were boys from all over the nation in its ranks.

Its Great War nickname was Old Hickory, but in World War II it became known as the Thunderbolt Division. The 83rd trained for nearly two years before it saw its first combat. Its three infantry regiments were numbered 329, 330, and 331.

Along with the rest of the 14,000-man division, Frank Fauver, a telephone lineman with G Company, 329th Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division, crossed the English Channel and landed in Normandy, France, on June 23, 1944—two weeks after D-Day. It was the beginning of the 83rd Infantry Division’s entry in World War II’s European Theater of Operations. In 2013 Fauver spoke to WWII Quarterly. During these conversations Fauver remembered pieces of the past: the landing at Normandy, the battles for Brittany, central France, Luxembourg, then Germany’s Hürtgen Forest, the Battle of the Bulge, and the race to the Elbe. Time had dulled his memory somewhat, but the pain of war remained.

“I was with frontline telephone communications,” Fauver recalled. “My job was to lay and maintain the wires that were right up front. At first I was scared to death, then after so many days up there at the front, we kind of came to the conclusion that we’re not going to get out of this alive and we’re going to give them Germans all we got. Then we didn’t worry about dying because we knew we were gonna.

“We were the forgotten boys. I’m not looking for glory; I’m looking for recognition for the ones who didn’t come home. There’s no glory in a war.”

“When we got home,” he said, “we knew if we tried to talk to somebody, they wouldn’t believe what we would tell them anyhow, so we didn’t talk about it. I spent a lot of time having a beer with buddies, but even then we didn’t talk much about it. We didn’t ask many questions because we wanted to put the war behind us. The real horrible parts were pushed out; it would eat you up if you didn’t.

“We had an awful lot of men who just broke, literally collapsed, from stress; war is not something a normal human being is used to. We turned over five times; every man was replaced five times, but not every man was replaced, do you understand what I’m saying? Our replacements were five times our original number. We had 270 days of actual contact with the enemy, in other words we were out there fighting. We just made up our minds we weren’t going to get out of it alive and to do the best darn job we could over there till the next shell got us. We were the closest Yanks to Berlin when the war was over. That was us, the Thunderbolts.”

During Fauver’s service as a qualified lineman in telephone communication, switchboard operation, and telephone line installation, he said he installed some 11,900 miles of telephone wire needed between the commanders at regimental headquarters and the frontline troops as they battled German forces across Europe.

Two weeks after the 21-year-old farm boy from Wauseon, Ohio, was inducted on October 13, 1942, he reported to Camp Perry, Ohio. After that it was training at Camp Atterbury, Indiana, then field training in Murfreesboro, Tennessee, and Ranger training at Fort Breckinridge, Kentucky.

“I trained in G Company,” he said, “but fortunately I got transferred to Regimental Headquarters because of my high points. When you go in the Army, you take an IQ test, and they gauge you by your intelligence, so to speak, according to the high points. I don’t know what I scored, but I got transferred. They didn’t tell you anything in the Army but ‘do it.’”

On April 6, 1944, Fauver and the division embarked on a 10-day voyage from New York aboard a British transport vessel named HMS Samaria. Fauver was seasick the entire trip; he recalled that halfway through the voyage, as he was “feeding the fish” over the side, he lifted up his head and saw a “thing” in the distance coming his way. That “thing” racing toward him was on top the water and looked like a big fish.

Fauver remembered, “At first I thought it was a whale. I had never seen one, and so I turned around and said something to one of the sailors. I think he was the only one on deck. He took one look at it and never said a word to me. He called down to the quarters where they run the ship and gave a full speed ahead and a hard left turn. I found out it wasn’t a big fish but a torpedo skipping across the water. If I had not been on the deck that day, the torpedo would have gotten our ship.

“And, like a fool, I wanted to see if it was going to miss us so I went back to the tail end of the ship. I don’t think it missed us by more than 10 feet. It went right on past us and went through the whole convoy and never touched a ship. Afterward, I found out my ship was part of the largest convoy that ever crossed the ocean. When I landed in Liverpool, England, on April 16, it was my 22nd birthday and [reaching solid ground] was the nicest present I ever had; I had been seasick all the way over.”

After disembarking at Liverpool, Fauver’s division moved to Wrexham, Wales. For two months the division trained in the Midlands and northern Wales, and then, shortly after D-Day, the 83rd was assigned to the First Army. Around June 20, the 329th Infantry boarded an LST (Landing Ship, Tank) bound for Normandy. Life would never be the same from that day forward.

Fauver recalled that the seas were so rough in the English Channel that, as one man climbed down the rope to board the LST, he was crushed between the two vessels. Fauver said the man’s screams stayed in his head the rest of his life.

The accounts written by Raymond J. Goguen, author of 329th “Buckshot” Infantry Regiment: A History, and published in occupied Germany in July 1945, conveyed the cross-Channel journey still fresh in the men’s minds: “We grappled with the rope ladders descending heavily into the LSTs. On these, we were soon ferried to the blood-spotted shores of Normandy…. Moving past shores, our heads bent as we saw freshly dug graves with their immaculate white crosses just recently planted into the soft ground.”

Baptism In the Hedgerows

Around June 26, the 83rd Division reached an area near Carentan, France, and took part in the hedgerow battles. The fighting in this sector, which was heavily defended by German SS, panzer, and airborne troops, was considered some of the most difficult of the war. The three-to-five-foot-tall and equally wide earthen hedgerows prevented Allied units from seeing beyond the next embankment and made the American tanks easy targets for antitank fire.

According to Goguen, “The 4th of July, 1944, will always live in our memories, especially in the ones of our 2nd Battalion.… On that day, the 83rd Division, as part of the VII Corps, attacked south of the town of Carentan.… The terrain … consisted of nothing but the hedgerows so typical of Normandy. In addition … the battalion was confronted by a swamp. Those who attempted to cross the swamp were either killed or left to bleed in the waist-deep marsh; few returned. Leaders and non-coms died gallantly in trying to lead their men to an almost impossible objective.

“We began to feel the loss of our dead and wounded, for casualties were mounting rapidly. We wondered if every day of combat on this continent would be as terrible as those we had just fought. With hidden tears we hardened at the sight of our buddies lying dead along the embankments of the hedges. We cursed aloud as brave medics and litter bearers carried moaning soldiers with limbs torn off and others with loose flesh staining the stretchers red. We refused many meals, for the sight and smell of decaying human flesh and cattle was simply too much for our nervous stomachs.

“We spent long sleepless nights, our bodies hugging the ground of foxholes, as shells whistled and lighted nearby, rocking and shaking the earth beside us. Was it possible for a man to live through all of this? We wondered when our turn would come. We cried to all known powers that someday the German race would suffer tenfold for all the suffering and human sacrifices we were enduring.”

Fauver, too, recalled the 4th of July attacks in the hedgerows: “There was fierce fighting between Sainteny and Carentan. The officers had maps and stuff, but none showed a swamp, and our division attacked right through it and, because of that, we lost near a battalion of men. The Germans just mowed them down like ducks. You know when you get in a swamp you can’t move. You are in mud and sink down. If you get in far enough, you could sink in clear over your head.”

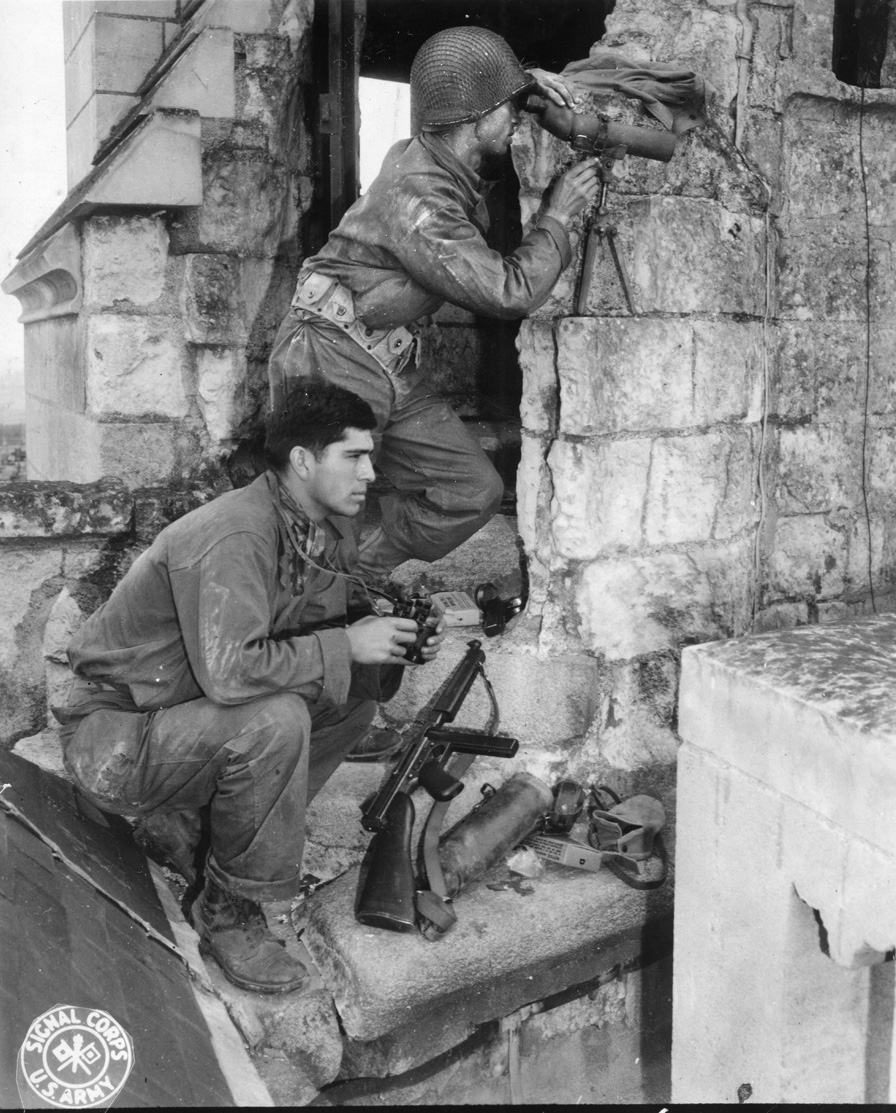

Once out of the marsh, Fauver worked at night stringing telephone wires along the narrow roads between hedgerows, which required the headlights and tail lights on the jeeps to be covered so only small slits of light would come through.

Fauver also remembered that jeeps were driven with the windshields down. Vertical bars extending above the heads of jeeps’ occupants had to be welded onto the front bumpers because the Germans had strung wire across the roads neck high. “Some of the guys driving jeeps were getting decapitated from the wires if there wasn’t something on the jeep to break the wires,” explained Fauver.

“There was usually a hole or opening in the corner [of a hedgerow] or someplace where the Germans could get in and out with their machinery,” he continued. “They dug into these hedgerows when we first started coming across the field. We were sitting ducks the first time; they just murdered us. It was terrible; we had terrific casualties. They darn near wiped out G Company, which was my own company.”

During this time, while Fauver’s division was fighting in the hedgerows, he recalled a visit by Supreme Allied Commander Dwight D. Eisenhower and General Omar Bradley. When the Germans started shelling his position, Fauver dove into one of the nearest trenches and landed on Ike’s shoulders. Fauver attempted to get out, but Eisenhower pulled him down and said, “There’s room enough for two, soldier.”

By now, the Allied juggernaut that had invaded France on June 6 was unstoppable. In his memoirs, Crusade in Europe, Eisenhower wrote, “By July 2, we had landed in Normandy about one million men, including 13 American, 11 British, and one Canadian division. In the same period we put ashore 566,648 tons of supplies and 171,532 vehicles…. During these first three weeks we took 41,000 prisoners. Our casualties totaled 60,771, of whom 8,975 were killed.” Also during this time, 400 members of the 83rd’s 329th Infantry died.

Cracking the Citadel

On July 25, the Normandy breakout of the hedgerows, known as Operation Cobra, began near St. Lô. The Americans feinted toward the Brittany peninsula, tying up four German divisions there. The recently activated Third Army, led by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, Jr., then moved eastward toward Argentan, while the British drove from Caen toward Falaise.

In early August, the 83rd (now transferred to Patton’s Third Army) headed west into Brittany through Coutances and Avranches toward the coastal towns of St. Malo and Dinard. Inside the fortified city of St. Malo, the citadel was held by German troops led by General Andreas von Aulock, who declared, “I was placed in command of this fortress; I did not request it. I will execute the orders I have received and, doing my duty as a soldier, I will fight to the last stone. I will defend St. Malo to the last man even if the last man has to be myself.”

Fauver said, “On August 3 our division was moved to Brittany and St. Malo, France. We had very few casualties; but we could not touch that fortress. We even had an air corps come over and drop blockbusters. I don’t know how they mixed that concrete, but it was so solid that those big bombs just bounced instead of tearing up the fortress.”

In the 83rd Infantry Division history (1962), the authors wrote: “Day after day, squadrons of bombers dropped tons of bombs on the Citadel; the artillery pounded it from every conceivable angle; even those immense eight-inch Corps Artillery guns were brought up within 1,000 yards of the Fort and fired point blank at it. The three-inch towed TDs [tank destroyers] fired hundreds of rounds of armor piercing ammunition with no visible effect.… ‘Mad Colonel’ von Aulock commanded the areas from an underground fortress, with 20 feet of solid rock overhead.”

U.S. intelligence estimated that between 3,000 and 6,000 German troops occupied St. Malo, but actually the number was closer to 12,000 defending the walled city. On August 6, the Germans demolished all the quays, locks, breakwaters, and harbor machinery and set fire to the city; then, on August 9, they retreated back to the citadel. Despite house-to-house battles, artillery fire, and fighter-bomber attacks, Aulock finally surrendered after his artillery and machine-gun emplacements were destroyed by direct hits from American 8-inch guns.

Fauver said, “We tried to get von Aulock to surrender several times, and he would say, ‘I’m a German soldier and German soldiers do not surrender;’ well, he did surrender on the 17th. He came into St. Malo all decorated in dress parade with all these awards; this was von Aulock.”

The 83rd captured 12,393 Germans in this battle.

Into the Loire Valley

After St. Malo, the 83rd moved to the Loire Valley to protect the entire right flank of Patton’s Third Army as it moved across France. The mission began on August 22 and lasted for about a month. The division’s zone extended from St. Nazaire eastward along the Loire through Nantes, Angers, Tours, and Orleans to Auxerre. This was a distance of more than 200 miles—the longest line of responsibility given any division in the war.

Fauver commented: “They moved us out of there and we went south to the Loire River. We had a sector that was over 100 miles long, which is almost unheard of for one division. It was pretty much a motorized patrol with the jeeps. The Germans were on one side of the river, and we were on our side of the river. Sometimes, when you were out in the open you could look over and see the Germans and they could see us. I remember every once in a while they would take a pot shot at us and sometimes would wave at us, which was rather unique. We would wave back; we tried to get them to like us so they would quit.”

During the division’s month on the Loire, some 20,000 Germans, including Brig. Gen. Botho Elster, were captured; formal surrender ceremonies were held at Beaugency Bridge on September 17. General Elster handed over his pistol to 83rd Division commander Maj. Gen. Robert C. Macon, and then his 20,000 men marched to a prisoner of war enclosure—the largest mass surrender of the war of German troops to Americans. During the operation, the 83rd was transferred from Patton’s Third to General William H. Simpson’s new Ninth Army.

“After that battle they moved us to Orleans, France. We were there for quite some time, just doing holding, and occupation, and reorganizing, and absorbing replacements and supplies so we would be ready. While we were there in Orleans, our intelligence went down across the river and did some reconnaissance. They ran into the Free French, the people who were against the Germans, who told them that some Germans down there would like to surrender.

“I was not involved in that but I do know they arranged for the German general to have a meeting. He wanted us to come and do a big bombing—not on his troops, but in his area to make it look good, and then he would surrender. We didn’t do that, and they argued back and forth, but eventually he did surrender. The Germans marched to Orleans with full equipment. We had some of our troops marching on the side to keep the Free French from shooting at them and to keep the peace.”

On September 24, the 83rd Division rolled rapidly eastward across France and into Luxembourg to take up positions along the Moselle and Sauer Rivers and relieve elements of the 5th Armored and 28th Infantry Divisions.

Hell in the Hürtgen

The losses for the U.S. Army in the Hürtgen Forest were great, with at least 33,000 killed and incapacitated, including both combat and noncombat casualties; German casualties were 28,000. The ancient city of Aachen, Germany, eventually fell on October 22, 1944, but at a high cost to the U.S. Ninth Army. The Hürtgen was so costly a battle that Field Marshal Walter Model called it an “Allied defeat of the first magnitude.”

The Battle of the Hürtgen Forest, the objective of which was to stop German forces from reinforcing the front lines farther north in the Battle of Aachen, was the longest battle on German soil during World War II and the longest single battle the U.S. Army has ever fought. The battle area covered 50 square miles east of the Belgian–German border and lasted from September 19 until December 16, 1944.

The division historians noted in The Thunderbolt Across Europe, “Approximately in the center of the triangular area marked by Aachen, Duren, and Cologne lay the Hürtgen Forest. It was here that the men of the 4th Infantry Division were fighting, fighting and dying. In this thickly wooded forest, Jerry easily concealed himself and his weapons. It was a forest filled with death. There were many Heinie snipers; there were machine guns, mortars, and camouflaged and entrenched Nazis with rifles and burp guns.

“Besides all this, there were the ever-deadly tree bursts—artillery shells fired so that they would explode near the tops of the trees and send fragments flying in all directions. In places, nearly every tree contained a booby trap and nearly all the space between the trees was covered with mines.…

“It was here that the 83rd was to be committed. Our mission was to relieve the 4th Division, to continue through the Hürtgen, and to seize the west bank of the Roer River. This would be our first fight in Germany, our first engagement with the enemy in his homeland.”

Fauver recalled, “On December 9, we moved to the Hürtgen Forest and relieved a division that was up there; they were all shot to pieces. I don’t think they had 10 men left out of any company. They were really hurting.”

Jack M. Straus, another veteran of the 83rd, wrote in We Saw It Through: A History of the 331st Infantry Regiment, “On December 6, we gave our positions along the Moselle Valley to the 22nd Infantry of the 4th Division. We then moved by truck to the Hürtgen Forest east of Aachen to relieve the battered men of the 12th Infantry [of the 4th Division] in this densely wooded area of hell, mud, and snow.

“In this cold and depressing forest, we were greeted with Nazi propaganda leaflets which informed us we were ‘given a damnable Christmas present by being transferred to the famous Aachen sector where fighting is harder than anywhere else. It’s all woods here. They are cold, slippery and dangerous.’ They reminded us—‘Death awaits you behind every tree. Fighting in woods is hellish.’ But it took more than these silly notes to dampen our spirits. Even the nightly ‘serenades’ of enemy heavy artillery and their devastating tree bursts and intensive strafing from the Luftwaffe could not make us buckle. Still it was plenty tough, about the roughest experience we had since Normandy. It wasn’t enough that we lived in holes roofed with logs, ate K rations with a hot meal only once each day. Our feet got numb and our hands got blue from the wet and cold.

“Trench foot was our biggest nemesis. At every opportunity we removed our shoes and dried and massaged our feet, changing to dry socks. One man massaged the feet of another. Drying tents were set up near the battalion aid stations. As our companies came off the line, we visited the tents in rotation where our chilled bodies were warmed and our clothes, shoes, and socks dried. But the constant exercise of one’s feet was the only real safeguard against trench foot, and this was done right in the foxholes wiggling one’s toes as often as possible while sweating out artillery, mortar barrages and German counterattacks.”

Fauver said, “Some armchair strategists long before had ventured the opinion that Jerry, once he had lost his hold of the occupied countries, was beaten, and that he wouldn’t elect to muss up the sacred soil of the Fatherland by fighting for it.… We, ourselves, were soon to learn that Jerry was fighting, and fighting like hell, on his own soil.”

According to Fauver, “It was all mud, cold, hell…. It was a forest of tall pine trees, and the Germans constantly shelled us with tree bursts. The shells exploded at treetop level and shrapnel and pieces of pine flew everywhere. We managed to drive them [the enemy] back across the Roer River, and we took several prisoners. About that time, a new aspect of the war started to become clear to us. All the German prisoners were old men and young boys, some hardly strong enough to carry a rifle. That told us Hitler was sending in everybody he had.”

The Germans were desperate to keep control of the Hürtgen because it was to serve as a staging area for the Ardennes Offensive (which became known in the West as the Battle of the Bulge) that was already in preparation, and the mountains’ access to the Schwammenauel Dam at the head of the Rur Lake (Rurstausee) which, if opened, would flood low-lying areas downstream and prevent any Allied crossing of the river.

Jack Straus noted in We Saw It Through, “We slugged our way out of the forest, and hurling our might against the German town of Gey on December 10th, smashed one of the most formidable Nazi strongholds on the outskirts of the Hürtgen Forest and drove the stubbornly resisting enemy to the banks of the Roer River just south of Duren.”

“Such crack divisions as the 1st and 4th Infantry Divisions,” wrote Raymond J. Goguen, author of 329th ‘Buckshot’ Infantry Regiment, “had been fighting since November the 11th to clear the enemy from the Hürtgen Forest. Their main obstacles, and they were tough ones, had been the fanatical stand staged by die-hard SS troops; the extensive mine belts and booby-trapped trees, all part of the inner Siegfried Line; the heavy concentrations of artillery and mortar fire causing tree bursts to send hot shrapnel into many of the men, thus inflicting heavy casualties; and the bad weather with constant rain and poor drainage which caused a high rate of non-battle casualties.”

Goguen said that shelter for the Yanks consisted of log huts and dugouts built by the former units in the forest. “We built more log cabins and improved those left to us until these primitive dwellings provided us with sufficient cover; but they were still poor from the standpoint of comfort. The narrow roads with a thick, knee-deep layer of mud made the going tough for vehicles.”

The 329th Infantry Regiment jumped off on the attack at 10 am on December 12 with the objective of reaching the edge of the Hürtgen Forest and closing up on the Roer River. The goal for the first day’s operation was a north-south road running through a tiny, three-house hamlet known as Hof Hardt. Goguen wrote, “The spirited 2nd Battalion started its ball rolling when F Company, displaying great courage, rushed five machine gun nests with heavy rifle fire and rapid movement and, as a result, overran them.”

The next day, 3rd Battalion was ordered to take the town of Birgel. To reach Birgel, the battalion would need to pass through thick woods to within 500 yards of the town. According to Goguen, “Very little resistance was met while advancing to the edge of the woods.… At the same time that the artillery was smoking the town, I and K Companies advanced using, in the words of Lt. Col. [John C.] Speedie, ‘the most beautiful and perfectly executed marching fire ever witnessed.’ We were out of the Forest.”

The 83rd’s official history noted that the division’s “most distinguished hero of World War II was Sergeant Ralph G. Neppel of Gilden, Iowa. He received the Congressional Medal of Honor for his actions on December 14, 1944, near Birgel.… Sergeant Neppel was a machine-gun leader who calmly ignored a German tank about to overrun his position. A shell blew off his left leg, but the sergeant held his position and, with grenades, wiped out 20 Germans.

“A German commander found 19-year-old Neppel lying in the snow, and, either as a favor to a horribly wounded man, or in anger, because the American had killed so many Germans, he shot Neppel in the head. Neppel was wounded and left for dead; apparently the bullet was deflected by his helmet. The next morning he had to be chipped out of the ice and snow. The bullet left only a slight scar.”

Surviving the Bulge

On December 16, 1944, the fighting that became the last offensive by Nazi Germany in World War II began. As the Germans advanced, a large salient or bulge was created in the U.S. lines, giving rise to the name “Battle of the Bulge.” The front was more than 50 miles across and, at one point, the deepest penetration by the Germans was more than 50 miles.

No sooner was the 83rd starting to make good progress in the Hürtgen than Hitler’s great counteroffensive in the West was launched. Goguen wrote, “Although the German Army’s plan of penetration was farther south, the enemy facing us launched fierce counterattacks all morning long against the towns of Gurzenich and Birgel.… Germans infiltrated everywhere and powerful enemy tanks fired point blank into buildings from which we defended. With our bazookas, M-1s, BARs, and machine guns we returned the fire; hunted down the infiltrators and after a real hard battle, we successfully repulsed the attacks. The 329th Infantry Regiment had stood its ground again.”

From December 20-27, 1944, the Belgian town of Bastogne became a key part of the larger Battle of the Bulge. The goal of the German offensive was the harbor at Antwerp. Because all seven main roads in the Ardennes mountain range converged on the small town of Bastogne, control of its crossroads was vital to the German attack. And, of course, the 83rd was in the thick of the fighting.

Although official records show that the 83rd Infantry Division was committed to the campaign at Rochefort, some 50 miles northeast of Bastogne and drove northeast of the town, Fauver swears he was close by. Fauver said, “Our objective was to drive a point toward Bastogne at the same time another division from the south was doing the same thing. We wanted to meet so the Germans would be trapped, so we kept driving, but when we were about one or two city blocks from Bastogne, the order came to hold up and not to take another inch. We could look into Bastogne and see the [trapped 101st Airborne] soldiers in there; wave to them, holler at them.

“We wondered, ‘What’s going on?’ All we have to do is go down there and walk in with a rifle and there would be no resistance. About that time we heard a terrible noise from the rear, and here comes Patton’s Third Army. They rode up through and into Bastogne. Well, when the Stars and Stripes, which was our newspaper, came out, it said that Third Army did it all and that we weren’t even there. That didn’t go over very good.

“The highway into Bastogne was terrible. The only way to advance was to follow the tanks on foot or in jeeps because they would pack the snow down. You couldn’t even walk on the snow; if you did you would sink in, it would bury you. So we followed the tank tracks to lay our telephone line. We would throw it up on the banks where the tanks couldn’t get them, otherwise the tank treads would chew them all to pieces.

“They said that was the worst winter they ever had over there, but the snow didn’t stop us from putting down our telephone lines. We lost so many men. They lost their toes, legs, hands, and fingers from frostbite. It was terrible. It was worse than the enemy. I often wondered how many froze to death in that snow.”

The Battle of the Bulge remains one of the longest and bloodiest battles ever fought by the United States, with 83,000 American troops committed, as compared to 200,000-250,000 Germans. Casualty figures for both sides are staggering. Nearly 21,000 Allied soldiers were killed, while another 43,000 were wounded and 23,554 were captured or reported missing. German losses numbered 15,652 killed, 41,600 wounded, and 27,582 captured or missing. In addition, the Germans lost 1,400 tanks and 600 other vehicles.

The Rag-Tag Circus

Like most combat soldiers in World War II, Frank Fauver had his share of close calls. Once, while installing phone lines at the front, a German tank shot out the bottom of the pole he was working on, which left him hanging on wires. Another time, a German mortar shell blew the front wheel off his jeep and shot a piece of shrapnel through a five-gallon gas tank in the back, which fortunately did not explode.

Another close call came when he dove into a roadside ditch for cover from incoming artillery. A shell hit a few feet from him and blew a deep hole that completely covered him with dirt; his buddies thought he had been blown to bits. In all 270 days of combat and close calls, Fauver only received a small nick on his finger from flying shrapnel.

“I really had doubts I would come home alive,” he related. “I always said I made it through the war because I had two guardian angels watching over me––my birth mother and my adopted mother.”

In late March 1945, the 83rd was ordered to turn east and head toward Berlin. The division commandeered anything on wheels––from bicycles to motorcycles to horses from the surrounding German countryside––to make a mad dash across northern Germany. Because of these tactics it became known as the “Rag-Tag Circus.”

Fauver said, “After we crossed the Rhine on March 29, 1945, the Germans were already on the run, so we commandeered anything that had an engine and that would run. We just took off cross country from the Rhine to the Elbe. They called us the Rag-Tag Circus because when you looked at our convoy you couldn’t tell if it was German or American.”

The resulting cavalcade included many captured German vehicles, among them tanks, motorbikes, buses, and at least one fire engine carrying infantrymen and a banner on its rear bumper that read, “Next Stop: Berlin.” The division would not stop until it had secured a position across the Elbe River.

In a span of only 13 days, the Thunderbolts fought their way across 280 miles of northern Germany as unit after unit within the 83rd leap-frogged one another to continuously press the attack eastward, outracing even armored units to the Elbe River.

The 83rd Infantry Division history says: “The Thunderbolt caused the newspapers to run out of descriptive phrases. Reporters referred to ‘crack troops of the 83d,’ and the ‘ace, shock troops of the Ninth Army,’ but, to those who were there, the 83d was called the ‘Rag-Tag Circus.’”

Uncovering a human catastrophe

On April 11, 1945, elements of the 83rd discovered and liberated Langenstein-Zweiberge, a slave labor camp near Halberstadt that had been established a year earlier and was a sub-camp of the Buchenwald concentration camp system. The main Buchenwald camp, near Weimar, was discovered that same day by elements of the 6th Armored Division.

At its height, Langenstein-Zweiberge held 5,000-7,000 inmates from 23 different countries. When the 83rd arrived, the Yanks found some 1,100 surviving inmates in horrific condition, some weighing only 80 pounds. The prisoners told their liberators that they had been forced to work 12-16 hours a day in the nearby Harz Mountains, digging what was to become a vast, underground factory for fighter planes and V-2 rockets. Those too weak to work were murdered. Life expectancy was only six weeks. Deaths occurred at a rate of 500 per month.

One of the liberators from the 83rd was Dr. Kenneth Zierler, battalion surgeon with the 399th Armored Field Artillery. Alerted by two war correspondents traveling through the area, Zierler said, “They told me that there was a concentration camp nearby and that we could liberate it because, they had heard, the guards had fled two days earlier at the sound of our tanks rumbling down the road. They had demobilized themselves simply by changing into mufti and melting into villages.

“The ambulance driver, Corporal Henry Mertens, the two newsmen, and I took off. The gate was open. There were no guards. A handful of men, in the vertical-striped uniform of the concentration camps, had placed themselves near the gate, but no one had been able to bring himself to cross the line past the open and unguarded barrier to the world outside.

“As we descended from the ambulance, they kissed our shoes. We lifted them to their feet. These walking skeletons were young men, looking aged. They told us we were the first Allied personnel they had seen. Some were covered with lice. Their faces were drawn, pale and gray. Most of the living huddled in their huts on cots, too weak to stand. From a tree swung the corpses of two inmates, hanged just days before. No one had had the energy to climb the tree and cut them down.

“Many survivors were barely alive. They showed us a large pit, one of several, covered with earth and lime, containing, they said, about 350 bodies of those who had died during the course of their labors. We were told that most had died of weakness and disease, but that about 50 had been hanged as disciplinary examples.”

A Hungarian prisoner showed the liberators his back covered with bruises and welts. He said that two weeks earlier he had been beaten by a guard with an iron rod for the crime of eating potato peelings he had found on the floor of the guards’ kitchen.”

One of the correspondents spoke with a 20-year-old skeleton of a man. “His face was green with jaundice, his skin stretched taut over his skull.” Zierler said. The correspondent asked him what his offense was, why he had been imprisoned. ‘I am a Jew,’ he answered.”

The doctor went on. “Those who were able to walk swarmed about us in a variety of moods, many speaking at once, or trying to. Some voices were so feeble we could scarcely hear them. Some seemed to be mumbling madly. Most blessed us, thanked God, wanted to know when there would be food, when they would go home.

“Our aid station could not handle this catastrophe. I was in a hurry to return to base to call division headquarters to send evacuation units for the survivors.”

Elements of the 329th also came upon Eschershausen—an underground aircraft and tank parts factory, concentration camp, and slave labor camp—and freed some 6,000 inmates.

On to the Elbe

With anger at its enemy renewed by the discovery of the camps, the division rolled eastward. Frank Fauver noted, “One day when we were moving, we saw a German command car off to our rear. They were really making hay and when they came past us, I hollered ‘Germans!’ Then somebody fired just over their heads instead of shooting at them. Well, that got their attention. They thought that we were Germans but they took a second look at us and realized that the convoy that was moving was not German. So we commandeered their car, disarmed them, put them in the convoy, and took them with us, because we didn’t have time to take prisoners. We eventually ended up at the Elbe River.”

Reaching the Elbe on April 13, 1945, the 83rd made the first Western Allied crossing of the river within 40 miles of Berlin. According to the Thunderbolt’s commander, Maj. Gen. Macon, the division “set an infantry record by racing 215 miles across four rivers in two weeks to establish and hold the only American bridgehead over the Elbe.” The 69th Infantry Division’s historic meeting with Soviet troops at Torgau on the Elbe did not occur until April 29, 1945.

Fauver said, “When we got up to the Elbe River, we radioed our commanding general back at headquarters and said, ‘We have a bridge here to cross; what do you want us to do?’ We could have walked to Berlin because there was no resistance, but he said stop at the Elbe. He said, ‘Stay where you are and don’t take another half inch of ground.’ In other words, he meant business, no movement; so we just sat there as kind of an army of occupation for a while. That’s where we met the Russians—in the little town of Barby.”

But first, there was a battle for the river crossing at Barby, 25 kilometers southeast of Magdeburg. The April 28, 1945, edition of the division’s newspaper reported that the 329th Infantry was in a “knock-down, drag-out” fight for the bridgehead on the west side of the Elbe. While the 2nd and 3rd Battalions were battling their way into the town against a force of about 600 German soldiers, an engine pulling 90 freight cars started to cross the railroad bridge but was quickly destroyed by American artillery.

The Luftwaffe then made a rare appearance in the afternoon and began strafing the troops. The retreating Germans blew the bridge that night. One of the Yanks said, “The first thing I saw was a tremendous white smoke ring. That was followed by a thunderous explosion and billowing clouds of black smoke.” This was followed by an aerial bombing attack on 329th positions.

The next morning the 329th resumed its attacks and, after a few hours of house-to-house fighting, the white flags came out. That afternoon, the first assault boats were paddled across the 150-yard-wide Elbe while under sporadic fire from the opposite bank.

They did not get far. Because the 83rd was now within the Russian sector due to the new territorial lines drawn at the Yalta Conference in February, Fauver’s outfit was ordered to pull back from the Elbe. On May 6, 1945, the 83rd turned over its positions to the 30th Infantry Division.

Considerable debate has surrounded the decision to allow the Soviets to take Berlin. In his memoirs, Eisenhower wrote that Berlin “was politically and psychologically important as the symbol of remaining German power. I decided, however, that it was not the logical or the most desirable objective for the forces of the Western Allies.” For the British and Americans to invest any more lives in taking Berlin was, in Ike’s words, “more than unwise; it was stupid.”

Ike’s decision was a sound one in terms of potential British and American lives spared; Berlin cost the Soviets some 300,000 casualties, including 70,000 killed.

The Elbe was where the war ended for Fauver, but it also left him with the feeling that the 83rd was forgotten. His division had given its blood and sweat; being prevented from reaching Berlin cut deeply. Fauver wasn’t the only one who felt this way.

For years, veterans from the 83rd have argued that the division’s accomplishments were worthy of the Presidential Unit Citation, the highest award given to an Army unit. The division was nominated for the citation after Germany’s surrender but did not receive the award. The 83rd Division Association recently resubmitted its request in hopes that new documentation will bolster its case.

Such a quest is a long shot, however. The standards for the citation, as defined by the Military Awards Branch, are quite high. The unit must have displayed such gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in accomplishing its mission under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions as to set it apart from and above other units participating in the same campaign. Moreover, the citation is rarely awarded to a unit larger than a battalion. The officers of the association contend that the case for the 83rd merits a look, particularly for its actions in the closing days of the war in Europe.

In all, the 83rd covered some 1,400 miles in its race across Europe. The division fought against 36 major units of German infantry, panzer, and parachute divisions in eight major battles and fired off almost 22 million small-arms and mortar rounds. The 83rd’s losses were heavy, with 3,161 killed in action, 11,807 wounded, and another 459 who died from their wounds.

Overall, by war’s end the men of the 83rd Division were awarded one Medal of Honor, one Distinguished Service Medal, five Legions of Merit, 798 Silver Stars, 34 Soldier’s Medals, 7,776 Bronze Stars, 4,747 Purple Hearts, 271 Medical Badges, 20 Meritorious Service Unit Plaques, and 106 Air Medals. They were honored with 18 British awards and 65 French awards and credited with destroying 480 enemy tanks, 61 enemy planes, 29 enemy supply trains, and 966 enemy artillery pieces.

At war’s end, Maj. Gen. Robert C. Macon told his Thunderbolts, “To those of you who fought in Normandy, Brittany, the Loire Valley, Luxembourg, the Hürtgen Forest, the Ardennes, and during the drives to the Rhine and over the Elbe, there is no need to relive the experiences encountered or to remind you of the inspiration set forth to us by those of our comrades who were killed or wounded.

“For it is you who made this history, you who performed the heroic deeds recorded here, you who captured St. Malo, took 20,000 Nazi prisoners in one day, reached the lower Rhine before any other troops. It was you who set an infantry record by racing 215 miles across four rivers in two weeks to establish and hold the only American bridgehead over the Elbe.”

Fauver remained forever proud of his division and its considerable role in the Allied victory in Europe. He received the Expert Infantryman Badge, the European Theater of Operations Medal with five battle stars, the Bronze Star, the World War II Victory Medal, the American Theater Service Medal, and the Good Conduct Medal. He died in February 2014, just two months shy of his 92nd birthday, shortly after being interviewed for this article.

The stories of the boys of the 83rd—and all who served in World War II—are fast disappearing as the veterans pass away. They all deserve to be remembered.

My dad, Raymond C. Rudd was a Captain in the 83rd, 330. He also went to Ranger School at Ft. Breckenridge. He died in 2001 at the age of 81.

No such thing as a Congressional Medal of Honor.

The medal is normally awarded by the President of the United States, but as it is presented “in the name of the United States Congress”, it is often referred to (erroneously) as the “Congressional Medal of Honor”.

When I got to the St Malo part [of the story] I searched the german commander and found this. I had to post.

Then a curious thing happened. An elderly German, a naval cook, broke ranks and ran up and embraced a young American soldier. The German was lucky not to be shot and the guards lowered their guns just in time. But no one interfered when the U.S. soldier put his arms round the German. They were father and son. The German spoke good American slang and was allowed to stay out of the ranks and act as interpreter. He had been 14 years in American, he said, and went back to Germany just before the outbreak of war

https://www.tracesofwar.com/thewarillustrated/189/i-was-there-i-saw-the-mad-colonel-of-st-malo-surrender.asp