By Nathan N. Prefer

During World War II, the U.s. “Arsenal of Democracy” produced thousands of ships of all shapes and sizes for the war effort. There were aircraft carriers both large and small, battleships, destroyers, destroyer escorts, submarines, landing craft, salvage vessels, supply vessels, tankers, hospital ships and many others. One of the most prolific warships was the Cleveland-class of light cruisers, with 26 completed during the war.

The U.S. Navy became interested in light cruisers near the end of World War I, which it had begun with only three older cruisers in its fleet. Intended as scout ships for the fleet of battleships and heavy cruisers, the first light cruisers built for the post-war U.S. Navy were the Omaha-class of 10 warships. These were intended for commerce raiding, not unlike the earlier “privateers” and “commerce raiders,” hence the name “cruiser,” as well as scouts for the battle fleet.

But interest soon turned to heavy cruisers and no additional light cruisers were built before 1935. That year saw the building of the new Brooklyn-class that was so successful it became the basis for all future classes of light cruisers.

The next class of light cruisers launched by the U. S. Navy was the Cleveland-class. Named after the city of Cleveland, Ohio, the lead ship was ordered by the U. S. Navy on May 17, 1938, from the New York Shipbuilding Corporation of Camden, New Jersey. Her keel was laid down on July 1, 1940, and given hull number 423. She was launched November 1, 1941, and commissioned on June 15, 1942, as the USS Cleveland (CL-55).

The Cleveland-class light cruisers weighed 11,744 long tons and had a maximum weight of 14,131 long tons. The ship was an inch over 610 feet long, had a beam of 66 feet, four inches, and drew 26 feet, six inches of water. Powered by four steam boilers providing 100,000 horsepower, four geared turbines turned her four screws to achieve a maximum speed of 32.5 knots. Her range was given as 11,000 nautical miles at a speed of 15 knots. She carried aboard 1,255 officers and enlisted men.

Her armament included a dozen 6-inch (150mm) main guns arranged in four triple-gun turrets. These were aided by six dual-mounted 5-inch (130mm) guns used for antiaircraft protection. Additional antiaircraft protection was provided by four dual mounted 40mm (1.6-inch) Bofors antiaircraft guns and 13 single mounted 20mm (0.79-inch) Oerlikon antiaircraft cannons. She carried four float planes used for scouting and other reconnaissance duties that were launched from two stern-mounted catapults.

Cleveland was protected by a belt of armor ranging from three-and-a-half inches to five inches thick. The main deck armor was two inches thick while the turret and conning tower armor were somewhat thinner. As the war progressed, several modifications would be made to the Cleveland-class. Among these were the installation of a Combat Information Center (CIC), radar, and additional antiaircraft guns which added some 480 tons to her top weight, thus making her somewhat top heavy and decreasing her stability.

To address this issue, one of her catapults was later removed, as were some of the smaller antiaircraft guns. In addition, ballast was added, and the hull, redesigned to slope outward rather than inward, helped with the stability issue, which remained a constant problem.

The original order called for construction of 39 Cleveland-class light cruisers. But only 26 were actually being built. One additional hull was converted into a guided-missile class cruiser after the war. Nine of the hulls laid down as Cleveland-class cruisers were converted during construction into Independence-class light aircraft carriers; the last three hulls were cancelled when the war ended.

Thirteen additional ships of an improved Cleveland-class design were also ordered as innovations evolved from wartime experience, but of these only two of the Fargo-class were built. These ships had less top weight and a lower armament placement along with a lower superstructure to improve stability. The powerplant remained the same, but the boiler rooms had been arranged so that only a single smokestack was used on the Fargo-class.

Hull number 423 was launched November 1, 1941. Under the command of Captain Edmund W. Burrough, USS Cleveland (CL-55) left Chesapeake Bay on October 10, 1942. She joined a naval task force off the coast of Bermuda later that month and sailed with it to North Africa, where she supported the invasion of Fedhala, French Morocco, with her main guns. She remained off North Africa until November 12, when she returned to the port of Norfolk, Virginia.

The following month she was ordered to sail for the Pacific. On January 16, 1943, she arrived at Efate Island in the Vanuatu chain—north of New Caledonia and southeast of the Solomons—and was quickly put to work guarding troop convoys bound for Guadalcanal. During these voyages she participated in the Battle of Rennell Island, January 29-30, 1943.

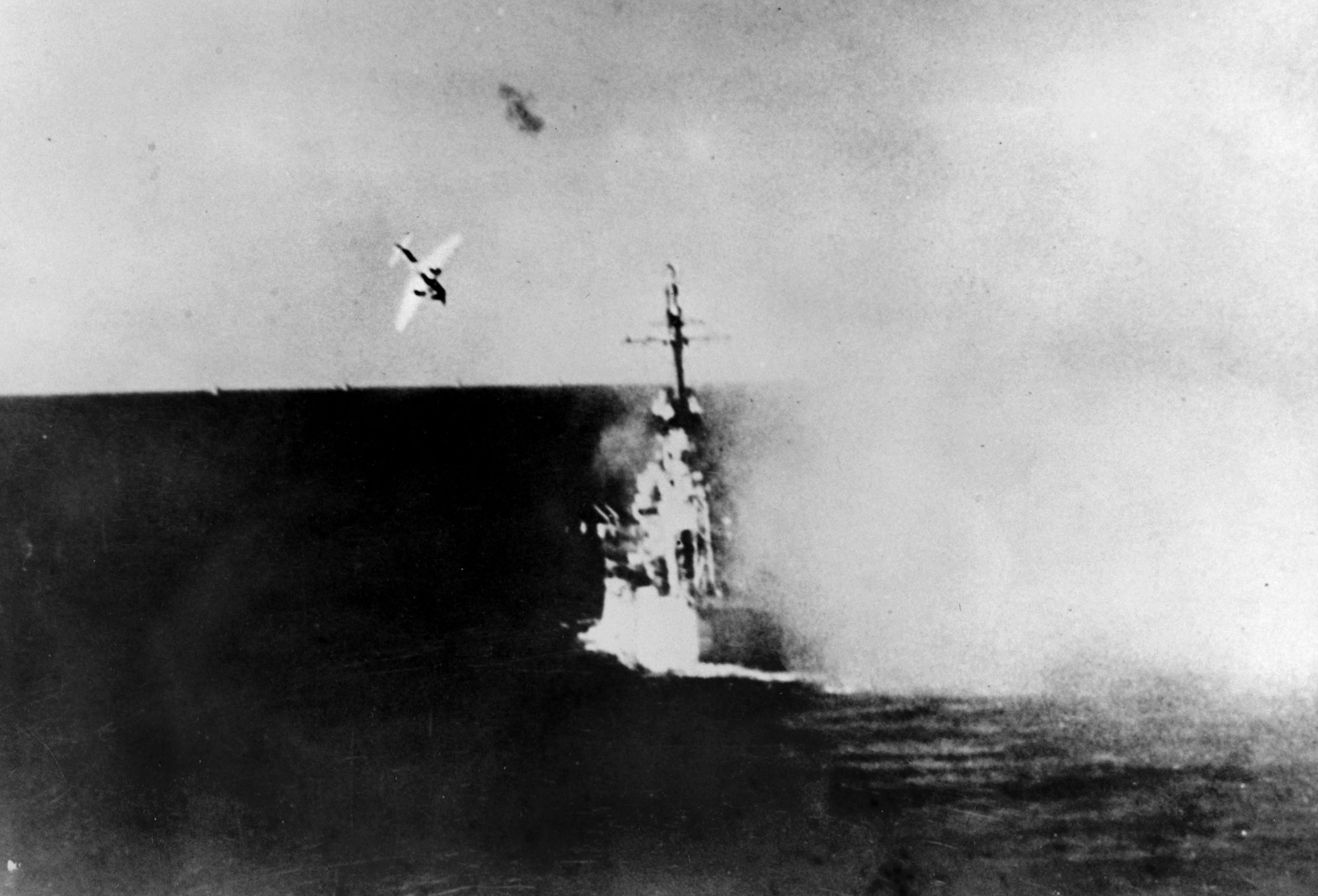

As a part of Cruiser Division 12, along with the USS Montpelier (CL-57) and USS Columbia (CL-56) and three heavy cruisers, Cleveland set out to bombard a Japanese base. Japanese aircraft appeared as darkness fell, and soon the task force was under attack by enemy torpedo bombers. Successive waves of enemy planes pursued the task force. Close calls were common, but no hits were scored until the USS Chicago (CA-29) was set afire by a crashing Japanese aircraft. A torpedo hit on the damaged ship followed.

Cleveland, in the adjoining column of ships, observed the entire attack, firing at the enemy. She then took part in the rear-guard action that protected the stricken heavy cruiser. But despite strenuous efforts to save her, Chicago soon sank.

Cleveland, now under Captain Andrew G. Shepherd, was then assigned to Task Force 68 and steamed up “The Slot” in the Solomon Islands to Kolombangara, where TF 68 was to bombard Japanese airfields. Along with Montpelier, Denver (CL-58), and three destroyers, Cleveland sailed west on a calm, moonless night.

The task force commander, Rear Admiral A. S. Merrill, then received word that two Japanese cruisers were heading in his direction. Merrill was not worried, knowing that this was probably another run of the “Tokyo Express,” bringing supplies to bypassed Japanese garrisons. In fact, however, these were the Japanese destroyers Murasame and Minegumo, not cruisers. Moments later, radar on the leading American ships picked up the enemy destroyers. Orders were sent to all ships to prepare to open fire.

The crash of the American cruisers’ 6-inch guns came as a complete surprise to the unsuspecting enemy destroyers and, suddenly, heavy gun splashes appeared all around them. The Murasame was hit by a salvo, then torpedoes from the USS Waller (DD-466) struck her, blasting the Japanese ship out of existence.

The Minegumo turned and tried to run, but the cruisers’ gunfire shifted to her and chased her as she ran. Within a mere three minutes, Minegumo was on fire and sinking. After this, the 16-minute bombardment of the Japanese airfield on Munda seemed anticlimactic.

Cleveland then sailed to Sydney, Australia, for routine maintenance and minor repairs. With these completed, she returned to the Solomon Islands and, while accompanied by Montpelier, Columbia, Denver, and a squadron of destroyers under Captain Arleigh A. Burke, bombarded Buka and Bonis airfields on November 1. Enemy planes struck at the task force but scored no hits. The task force then sailed to the Shortland Islands where another bombardment was executed.

The Americans’ next target was the large island of Bougainville. The landings were planned for Empress Augusta Bay and executed on November 1. The landings were successful, and the Japanese reaction swift. As soon as they learned of the new beachhead, the Japanese dispatched two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and six destroyers to contest the seaborne invasion.

Against this, Rear Admiral A. Stanton Merrill, sailing in Montpelier, had four light cruisers and eight destroyers to oppose the counterattack. With Cleveland, Columbia, and Denver joining him, he placed his force between the oncoming Japanese and the beachhead. Two hours into November 2 the battle was joined.

The resulting fight was a confused night battle. Despite their advantage in guns and torpedoes, the Japanese force was overwhelmed. With the first salvos, one Japanese light cruiser was badly damaged and two enemy destroyers had collided while trying to avoid being hit. A third destroyer smashed into one of the cruisers while dodging American salvos. Another Japanese heavy cruiser took six successive hits from the American light cruisers.

Meanwhile, the Americans were leading a charmed life; not a single Japanese shell or torpedo had found its mark. But that could not last, and Denver took three 8-inch shells in the forward part of the ship; fortunately none exploded. She did take on considerable seawater but remained in the action, albeit somewhat slower.

As if that were not enough, Japanese planes suddenly appeared and began bombing the American ships as they maneuvered.

After more than an hour of battle, the Japanese withdrew, reporting that they had fought off seven heavy cruisers and a dozen destroyers. One American destroyer, USS Foote (DD-511), had been hit by a torpedo and stopped dead in the water, forcing Cleveland to turn full rudder, missing Foote by a mere 100 yards.

The American cruisers pursued the retreating Japanese for more than 20 miles but never caught up. The Battle of Empress Augusta Bay cost the Japanese one light cruiser and one destroyer sunk, two heavy cruisers damaged, and four destroyers seriously damaged while the Americans had one ship (USS Foote) damaged. During the withdrawal, Montpelier’s starboard catapult was damaged by enemy air attacks, and Cleveland was rocked by several near misses.

After its busy days in the Solomons, with two bombardments and a major naval battle, all in 48 hours of intense action, Cleveland retired with the task force to Purvis Bay. For her action in the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, Cleveland would be awarded the Navy Unit Commendation.

Following a brief rest, she performed another bombardment of Buka and then patrolled around the Green Islands and Papua, New Guinea, until mid-February 1944. In March she supported the invasion of Emirau Island before returning to Sydney, Australia, for maintenance and minor repairs.

By June 1944, the refitted Cleveland was back at war. She was now a part of the “Big Blue Fleet,” fighting its way across the Central Pacific. Beginning on June 13, she participated in the pre-invasion bombardment of Saipan in the Mariana Islands. In this she was joined by eight battleships, six heavy cruisers, and four other light cruisers. This continued into the following day, and the shelling now included the nearby island of Tinian.

While joining the battleship USS California (BB-44) in bombarding the small island, Cleveland was fired upon by a shore battery that straddled the light cruiser and hit the battleship, killing three and wounding 15. Cleveland returned fire and claimed to have destroyed the enemy field artillery piece that did the damage to California.

The next three weeks were spent answering calls for fire support for the Marines and soldiers fighting on Saipan. By July 1 the enemy had been pushed back to the north end of Saipan, Marpi Point, and was fighting desperately. At the request of the 4th Marine Division, the cruisers Cleveland, Montpelier, and Birmingham (CL-62) bombarded these hold-out positions with their six-inch guns and used their 40mm guns to pepper enemy troops moving along the beaches.

The Japanese objected strenuously to the invasion of the Marianas and came out to do battle with their entire fleet. The resulting clash, the Battle of the Philippine Sea, was almost completely an air and submarine battle, with the surface ships never coming within sight of one another.

Cleveland and several of her sister ships provided antiaircraft protection for the American aircraft carriers that carried the main burden of this battle. During this fight, Cleveland was credited with one Japanese plane shot down and another “probable.”

With the fall of Saipan, the Americans turned their attention to nearby Tinian. The assault began on July 24, 1944, and once again the U.S. Navy provided support with its heavy guns. During this bombardment the destroyer USS Norman Scott (DD-690) was hit six times by enemy field batteries, killing the captain and 18 sailors. Cleveland moved between the damaged destroyer and the shore battery to act as a shield and prevent any more hits on the destroyer, all the while firing back at the enemy gun.

Cleveland, the destroyer USS Remey (DD-608), and battleship California combined to silence the offending shore battery, but it would take an additional bombardment by battleships to finally knock out this gun.

The increasing tempo of American invasions next targeted the Palau islands, and once again Cleveland was offshore providing bombardment support upon call from the Marines and soldiers ashore. Relieved for a stateside repair segment, the Cleveland returned to the United States and spent three months undergoing repairs and having her radar and other systems upgraded. By February 1945, she was back in the Pacific, at Subic Bay in the Philippines, participating in the Americans’ return to the Philippines.

As part of Cruiser Division 12, partnered with Denver and Montpelier and escorted by four destroyers, Cleveland’s guns bombarded Corregidor before the landings there, and then participated in several landings throughout the Philippines. The division bombarded Puerto Princesa in mid-February and, in April 1945, Cleveland supported the landings on Mindanao along with the destroyer USS Sigourney (DD-643).

By July 1945, Cleveland was supporting the Australian invasion of Balikpapan, Borneo, and serving as the command ship for General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Together with USS Phoenix and USS Nashville, the light cruiser participated in a two-hour bombardment.

The Japanese returned fire, and several ships were straddled, but no damage or casualties resulted. Once the Aussies had established themselves ashore, General MacArthur and Cleveland returned to Manila Bay, in the Philippines. Cruisier Division 12 remained behind to continue supporting the Australian operation.

Cleveland next sailed to Okinawa, arriving there on July 16, 1945, and joined Task Force 95, which made a series of sweeping attacks along the Japanese coastline. These lasted until August 7 and ensured American control of the East China Sea.

By September 9, Cleveland was sailing to support the occupation of Japan and to cover the evacuation of Allied prisoners of war from Japan. She then served as a part of the occupation force until the Sixth U.S. Army landed on the Japanese island of Honshu.

Cleveland spent a few days in Tokyo Bay before sailing for Pearl Harbor, then San Diego, through the Panama Canal, and finally to Boston. She arrived there on December 5 for a much-needed overhaul before beginning training cruises and working as a part of the Naval Reserve, taking reservists for cruises to Bermuda, Quebec, Halifax, and Nova Scotia. But her days were numbered.

In 1947, with the war over, Cleveland was ordered to report to Philadelphia for inactivation, where she remained, rusting away, her glorious war record forgotten until sold for scrap in February 1960. In addition to her Navy Unit Commendation for the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, Cleveland earned 13 battle stars for her World War II service. Along with Montpelier and Santa Fe, this was the most battle stars credited to any ship in the class.

The Cleveland-class light cruisers were a hurried design rushed to completion when it became apparent that the United States was unavoidably being drawn into a world war that would entail considerable naval conflict. The U.S. Navy even acknowledged that these relatively light ships could be sunk by one torpedo hit but pushed for them anyway. Yet, in battle, not one Cleveland-class cruiser was lost to enemy action. USS Houston took three torpedo hits and survived, while several others survived a single torpedo hit. Others survived strikes by kamikazes.

The Cleveland-class cruisers did provide excellent fire support—both for troops ashore and the battle fleet at sea. The rapid-firing 6-inch guns exceeded those of all other navies with their rate of fire and were responsible for many killing strikes on enemy ships and numerous aircraft.

In the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, these light cruisers beat off a superior Japanese force of heavy cruisers, sinking one and damaging several destroyers. They and their gallant crews deserve their honored place in history.

A frequent contributor to WWII History, Florida-based Nathan Prefer is the author of many books about World War II, including Leyte 1944: The Soldier’s Battle; Vinegar Joe’s War; Patton’s Ghost Corps; and The Battle of Tinian.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments