By Michael E. Haskew

The reason for it was unthinkable. The Gothic Line, the last line of defense in Italy, was necessary, but senior German commanders had not been concerned that it would ever be contested by Allied forces. Before the actual inception of the Italian campaign, preliminary plans for a strong defensive line in the northern Apennine Mountains were approved, and by the summer of 1944, the unthinkable had become reality.

To the north of the Apennines lay the broad expanse of the Po River Valley and the Plain of Lombardy, favorable ground for the movements of a modern, mechanized army. Field Marshal Erwin Rommel, who had preceded Field Marshal Albert Kesselring in command of German troops in northern Italy, recalled his earlier service with the Army in World War I and favored a line even farther north, in the Alps. Rommel, however, was overruled. (Take a deep dive into every front and conflict in the Second World War: subscribe to WWII Magazine today.)

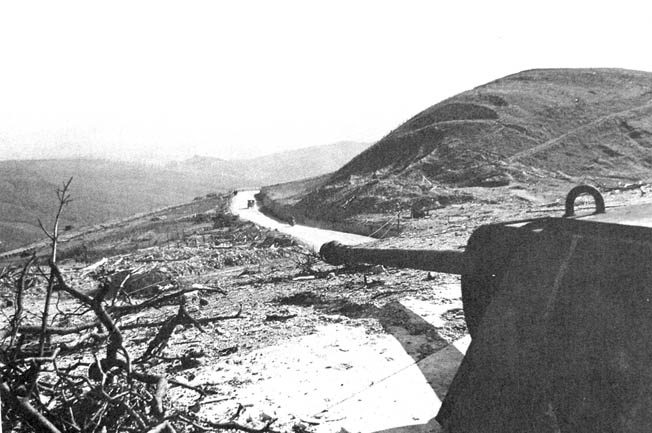

Defending the Apennines would, it was hoped, deny the Allies the tactical advantage that seizing the favorable Po Valley terrain would mean, for there the cities of Bologna, Modena, and Milan—and the rich agricultural land that provided much of the food for the Axis—lay. Hitler had further decreed that the territory was to be given up only grudgingly, and Highway 9, the only good road running east to west in northern Italy, would allow the Germans to transfer forces with reasonable speed.

Pushed Back to the Gothic Line

By August 1944, German forces in Italy had been in retreat or fighting a skillful defensive war for more than two years. They had been pushed off the African continent, forced to abandon Sicily, and compelled to execute a fighting retirement up the boot of Italy. Losses in tanks and other vehicles were irreplaceable as the Reich was pressed by the U.S. and British armies in France and by the Soviet Red Army advancing inexorably from the east. Casualties were high, and there were few quality replacements available.

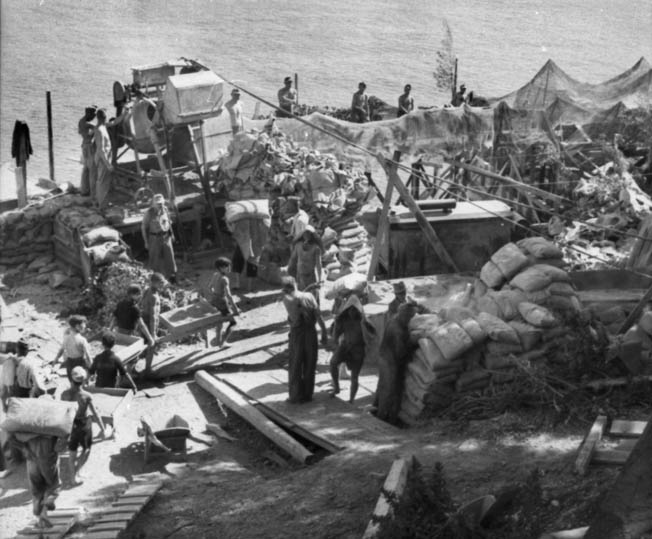

In the spring of 1944, the focus of the Todt Organization, Germany’s paramilitary construction arm, was the building of the Gothic Line, finally a priority for Kesselring following months of preoccupation with events farther south. Augmented by conscripted Italian workers, many of whom were rounded up in the streets of the country’s large cities, the Germans were hastily building a thick band of defenses that stretched 200 miles from the naval base at La Spezia in the west, across the Apennines and the Foglia Valley, to the Adriatic port of Pesaro.

While any German troop movement of appreciable size and any Allied offensive thrust along either Italian coastline would be within range of overwhelming U.S. and British naval firepower, control of the air had long been conceded to the Allies. Tactical airstrikes could devastate German columns moving during daylight hours, and the Fifteenth Air Force, based at Foggia, conducted daily raids on industrial targets in northern Italy and in Germany. By the spring of 1944, the manpower of the Fifteenth Air Force topped 50,000, while more than 1,200 heavy bombers, most of them Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators, were dropping tons of bombs.

The realists among the German commanders harbored no illusions of victory, but they were grimly determined to make the Allied ground troops pay as dear a price as possible for every successive yard of Italy. Allied senior commanders, on the other hand, hoped to breach the Gothic Line and race into the Po Valley before winter.

Facing supply and manpower shortages of their own, the Allies did possess the ports of Leghorn on the Ligurian coast and Ancona on the Adriatic. These were only about 35 miles from the front lines, much closer than smaller ports and the facilities at Naples, which had been wrecked by the retreating Germans following the American landings at Salerno in September 1943. Therefore, a breakthrough might be sustained more efficiently and allow for more rapid movement to the north.

During the two weeks prior to the early August attempt of the II Polish Corps to cross the Metauro River in the east, tactical aircraft had flown nearly 400 sorties against German positions. The Poles hammered at the German 278th Infantry Division and drove it back beyond the Metauro, losing 300 dead in heavy fighting. On August 25, 1944, the Eighth Army renewed its offensive operations with the V Corps and the 1st Canadian Corps advancing rapidly across the river. Three days later, the Germans withdrew the LXXVI Panzer Corps and the LI Mountain Corps into the defenses of the Gothic Line.

Lieutenant Norton Takes on Monte Gridolfo

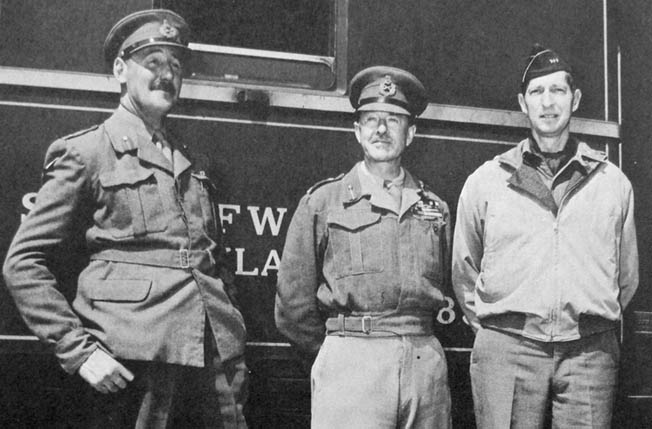

Rapidly moving on Pesaro, the Eighth Army, under General Oliver Leese, was poised to outflank the eastern end of the Gothic Line. First, the strongpoint of Monte Gridolfo had to be neutralized. Elements of the 26th Panzer Division had taken up positions around the town only hours before the first British troops arrived. Leading a platoon in the attack of August 31, Lieutenant G.R. Norton of the 1st Battalion, 4th Hampshire Regiment won the Victoria Cross as his men took on a series of concrete bunkers but became pinned down by fire from their right flank.

The 4th Hampshire regimental history relates, “On his own initiative, Lieutenant Norton at once went forward alone and engaged a series of enemy positions…. he attacked the first machine gun position with a grenade, killing the crew of three; then, still alone, he worked his way forward to another enemy position containing two machine guns and fifteen riflemen. After a fight lasting ten minutes he wiped out both machine guns with his Tommy gun and killed or took prisoner the rest.

“Throughout these engagements Lieutenant Norton was under direct fire from an enemy self-propelled gun and, still under fire from this gun, he led a party of men who had come forward against a house and cleared the cellar and upper rooms, taking several more prisoners and putting the rest to flight. Although by this time he was wounded and weak from loss of blood, he went on calmly leading his platoon … and captured the remaining enemy positions.”

When Norton was later evacuated to a field hospital, the nurse assigned to care for him turned out to be his twin sister. The next day was their birthday.

The Eighth Army’s Advance Winds Down

On September 2, the Poles outflanked the Germans at Pesaro. Canadian troops had already taken Tomba di Pesaro and driven a wedge between the 26th Panzer and 1st Parachute Divisions. The following day, the Eighth Army had penetrated 10 miles and compromised the Gothic Line defenses along the Adriatic. It appeared as if the months of work the German laborers had invested might derive no tangible benefit whatsoever. The stunning advance of the Eighth Army had netted 4,000 prisoners, and General Traugott Herr, commanding LXXVI Panzer Corps, established a patchwork defensive line along the Coriano Ridge.

The British 46th Division and the 1st Canadian Corps tried for more than three days to take the ridge, but the veteran German defenders held firm. During the week of September 3, torrential rain fell, stalling the Eighth Army effort. Beyond the Coriano Ridge lay the key positions of San Fortunato and the town of Rimini. With Rimini in their hands, the British hoped to exploit the Romagna Plain, believed to be good tank country with firm ground.

The deteriorating weather, however, proved to be a major adversary and sapped momentum from the drive. More than 8,000 casualties had been sustained, and the Gothic Line was behind them, but the troops of the Eighth Army were exhausted and facing fresh German reinforcements.

Mark Clark’s First Penetration of the Gothic Line

When the Eighth Army began its offensive, Kesselring wavered before committing precious German reserves. Events subsequently compelled him to pull troops from the center of the Gothic Line and move them eastward along Highway 9 to stop the advance on the Adriatic front. Credit must be given to General Harold Alexander, commander of 15th Army Group, who had foreseen such a turn of events and an opportunity for the U.S. Fifth Army, under General Mark Clark, to deliver a roundhouse blow against the weakened Gothic Line center, less than 20 miles north of Florence.

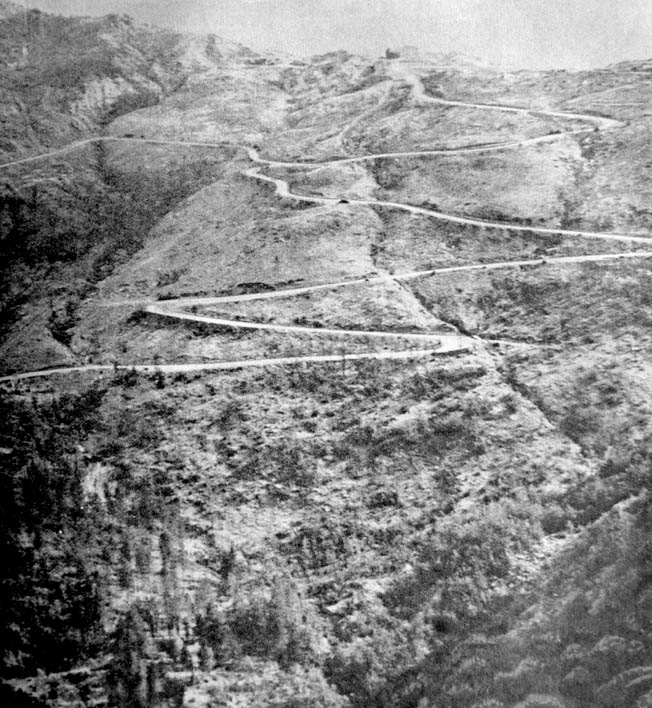

The bulk of Fifth Army crossed the Arno against only light opposition. Pisa, home of the famous leaning tower, was captured on September 2, and the II, IV, and XIII Corps moved ahead, IV Corps lagging behind somewhat against strong resistance along Highway 65. As Clark consolidated his gains, he considered two avenues of approach to the Gothic Line: Futa Pass on Highway 65 and Il Giogo Pass, six miles to the east. The Germans had placed stronger defenses at Futa Pass, believing that an Allied thrust would take the best road in the area.

Clark reasoned that advancing through Il Giogo Pass would outflank the strong defenses at Futa Pass, take Firenzuola five miles distant, and then facilitate a resumption of the advance along Highway 65 or a secondary road through Imola to the city of Bologna, 60 miles north of Florence and the gateway to the Po Valley. He also hoped for assistance from a renewed Eighth Army offensive toward Bologna.

When Fifth Army drew up to the Gothic Line on September 12-13, only one German regiment, the 12th Parachute of the 4th Parachute Division, held Il Giogo Pass; the two other regiments of the 4th were at Futa Pass. The capture of Monticelli, a 3,000-foot ridgeline on the left, and Monte Altuzzi, a peak of roughly the same height on the right, would force Il Giogo Pass open.

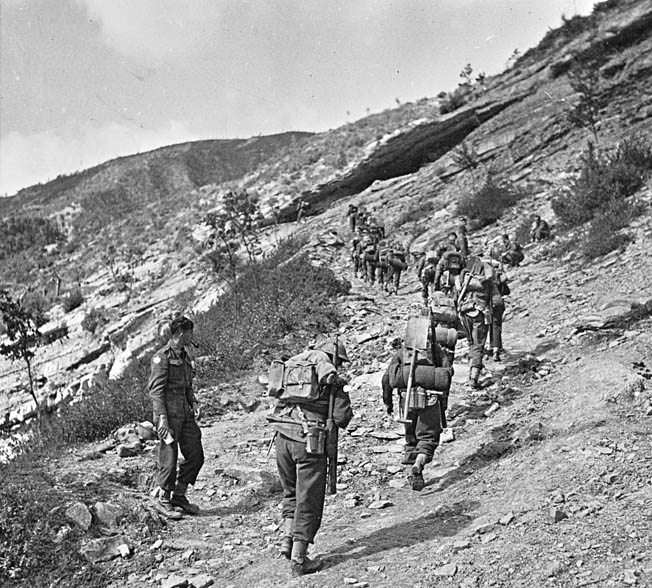

Two battalions of the U.S. 91st Division’s 363rd Infantry Regiment began the painstaking ascent of the western slope of Monticelli on the 13th and encountered heavy mortar and small arms fire. The vanguard of a Fifth Army fighting force that numbered more than 260,000 was at times reduced, due to difficult terrain and a determined enemy, to no more than a handful of soldiers clinging to a mountainside.

One company was stopped by German artillery. Under cover of darkness, an officer and six volunteers crawled forward to pinpoint the enemy position. The following day, accurate 155mm counterbattery fire from American artillery silenced the enemy. When a company of American troops moved forward and captured five dazed Germans, they had achieved the first penetration of the center of the Gothic Line.

Medals of Honor on the Gothic Line

The elite German Fallschirmjäger troops launched several violent counterattacks against the lodgment. During one of these, Sergeant Joseph Higdon, Jr., leaped from cover with a light machine gun. Firing from the hip, he forced the Germans to retire but was seriously wounded. He fell 30 yards short of his own line and died before medical assistance could reach him.

Private First Class Oscar Johnson, a member of a mortar crew, assumed the role of a rifleman when all his mortar rounds were expended. The six other members of his squad had been killed or wounded by the afternoon of September 16. Johnson collected weapons and ammunition from his fallen comrades and held his position through the night. His Medal of Honor citation reads, “On the night of 16-17 September, the enemy launched his heaviest attack on Company B, putting his greatest pressure against the lone defender of the left flank.

“In spite of mortar fire which crashed about him and machine-gun bullets which whipped the crest of his shallow trench … Johnson stood erect and repulsed the attack with grenades and small arms fire. He remained awake and on alert throughout the night, frustrating all attempts at infiltration. On 17 September, 25 German soldiers surrendered to him…. Twenty dead Germans were found in front of his position.”

Johnson was credited with killing more than 40 enemy soldiers, and 150 dead Germans lay in front of Company B. In return, the company had taken 75 percent casualties, its effective strength reduced to 50 men before Monticelli was secured on the 18th.

While the 363rd Regiment was fighting there, the 338th captured Monte Altuzzo after five days of hard fighting. Three U.S. divisions had sustained a total of 2,731 casualties in six days. On the night of September 17, General Joachim von Lemelson directed the I Parachute Corps to vacate the Gothic Line. Futa Pass was given up as well.

During a diversionary attack on September 14, which had kept the German defenders of Futa Pass from moving reinforcements to Il Giogo Pass, 2nd Lt. Thomas Wigle of the 135th Infantry Regiment, 34th Division, was hit when he led an assault near Monte Frassino, but drew fire to himself and allowed his command to maneuver over three stone walls. He then dashed into the first of three houses and drove the Germans out, followed them into a second, and routed them.

Wigle was mortally wounded on the steps of the cellar at the third house, where the enemy soldiers had sought refuge. Within minutes, 36 Germans emerged from the cellar and surrendered. Wigle received a posthumous Medal of Honor.

Opening the Gates to Rimini

Supported on air and sea, the British V and Canadian I Corps renewed their assault against Coriano Ridge on September 13. The Irish Regiment of Canada put a battalion of the 29th Panzer Division to flight and cleared the town of Coriano house by house.

The following day, the Canadians were two miles north of the ridge at the southern bank of the Mariano River. Both flanks of the German Tenth Army were bending precariously backward. The Canadians moved again on September 19, taking the San Fortunato Ridge, but bad weather stalled the Canadian armored spearheads.

Elsewhere along the line, floodwaters and thick mud slowed the entire offensive. Nevertheless, the loss of the San Fortunato Ridge made it impossible for the Germans to defend Rimini.

General Traugott Herr withdrew his Fourteenth Army troops from the city on September 20 but left intact a stone bridge across the Marecchia River, which had been built nearly 2,000 years earlier during the reign of the Roman Emperor Tiberius. The Triumphal Arch of Augustus, built in 27 bc, was also still standing amid modern ruins when the Canadians and the 3rd Greek Mountain Brigade rolled into Rimini.

Afterward, Kesselring wrote in his diary, “I have the terrible feeling that the whole thing is beginning to slide.”

Slowed by Poor Weather

When the Canadian tanks deployed onto the Romagna Plain, however, they found that the ground had been turned into a quagmire by the seemingly endless rain. Alexander had hoped to advance beyond the line from Pisa to Rimini, but such was not to be. In 26 days, the Eighth Army had advanced only 30 miles. “The plains so long hoped for and so fiercely fought for,” he wrote in a dispatch, “[were] clogging mud and brimming watercourses.”

Clark weighed his options at Il Giogo Pass and decided that a secondary advance to Imola could support the Eighth Army fighting north of Rimini along Highway 9 and cut off Germans falling back from the British attacks. The U.S. 88th Division advanced down the asphalt road into the Santerno River Valley and was obliged to capture high ground at Castel del Rio and a road junction beyond the town before reaching Imola.

Hard fighting in foul weather produced only limited successes as the Germans reinforced a vulnerable area between the Tenth and Fourteenth Armies. A battalion each from the 362nd and the 44th Reichsgrenadier Divisions defended Castel del Rio, but the American 350th and 351st Infantry regiments managed to take several peaks in the area, forcing the Germans to withdraw. The 350th Regiment occupied nearby Monte Battaglia, defending it against savage German counterattacks.

The terrible weather hampered the forward momentum of the IV Corps and slowed the advances of II Corps and XIII Corps to the east. Air support was fogged in, and the situation confronting Fifth Army became quite similar to that which had reduced the Eighth Army drive to stagnation.

The Germans, meanwhile, took advantage of the lull to deploy what reinforcements they could. Aware that his lunge toward Imola had caused the diversion of few German troops from the Eighth Army front and concerned that the single good road in the area could facilitate little freedom of movement for his troops, Clark abandoned the Imola effort and redirected the mass of Fifth Army strength toward Bologna.

At the end of the month, Bologna was only 24 miles away from II Corps’ positions along Highway 65 and, at Monte Battaglia, the Po Valley was only 10 miles distant from British troops. Clark was required to think of his overall position, and the three divisions of the XIII Corps were extended across 17 miles of the Santerno Valley while the IV Corps was holding a 50-mile front; neither was able to affect a rapid move forward.

Further, the commander had seen it necessary to pull the 1st Armored Division out of the line for rest. Therefore, the Germans were able to shift troops to the most-threatened sectors of their line while the uncertainty of autumn and winter weather served as a wild card for operational planners.

As so often had occurred during the Italian campaign, the objectives of the Allied armies seemed so near and yet so distant. Clark observed that he “could see for the first time the Po Valley and the snow-covered Alps beyond. It seemed to me that our goal was very close.”

“My Forces Are Too Weak Relative to the Enemy”

In reality, September was a time for Clark’s superior, General Alexander, to take stock. His assessment of the situation confirmed the sense of frustration that he had felt for some time. The official history of the U.S. Army in World War II relates, “Although September had seen both the Fifth and Eighth Armies make impressive gains by breaking through the Gothic Line and driving, respectively, to within sight of the Po Valley and moving northwestward along Highway 9, some 17 miles from Rimini to a point just east of Cesena, both were still far from their original goals of destroying the Tenth Army south of the Po and pushing the Fourteenth Army north of the river.

“The worsening weather and attrition of the September battles made it seem, at least to General Alexander, that those goals could not be gained in the near future.”

The U.S. Army history continues, “On 21 September Alexander informed the Chief of the Imperial General Staff [Field Marshal Sir Alan Brooke] that, although the Allied armies in Italy had inflicted severe losses on the enemy, Allied losses also had been heavy. The Allied commander [Alexander] added that the nature of the terrain in the mountains as well as in the Romagna Plain necessitated a three-to-one superiority in troop strength for successful offensive operations.

“Since his armies were not likely to achieve that ratio in the foreseeable future, General Alexander believed that decisive victory in Italy was no longer possible before the end of the year—a conclusion that the U.S. Army’s Chief of Staff, General Marshall, had reached in August.

“Five days later Alexander returned to the same theme in a message to the theater commander, observing that ‘the trouble is that my forces are too weak relative to the enemy, to force a breakthrough and so close the two pincers. The advance of both armies is too slow to achieve decisive results unless the Germans break, and there is no sign of that.’”

Livergnano and Bigallo

Continuing to focus on Bologna, General Geoffrey Keyes’s II Corps took the offensive on October 1 and managed to advance four miles in four days against the depleted 4th Parachute and 362nd Grenadier Divisions. Racing the calendar in anticipation of winter snow and ice, the Americans took nearly 900 prisoners but lost 1,734 killed and wounded.

Troops of the 91st Division entered the fight on October 5, capturing the town of Loiano and the heights of Monte Castellari. Progress was agonizingly slow. During four more days of fighting, the II Corps center moved forward but three miles.

The Germans fell back to the Livergnano Escarpment, which offered the best defensive positions they could take advantage of north of the Gothic Line. The high ground menaced a section of Highway 65 and caused Keyes to maintain his focus to the east, in the zone of the 85th Division.

Monte delle Formiche, nearly 2,100 feet high, stood in the way of the advance on the escarpment. Troops of the 338th Infantry Regiment captured the heights with artillery and air support, while taking 53 German prisoners and repelling a counterattack. However, they managed to advance only another mile during the next three days. The 337th Regiment, supported by a battalion of the 338th and later relieved by the 339th, captured Hill 578, but that was the extent of the 85th Division drive.

Two battalions of the 88th Division fought for three days before finding a gap in the German defenses, crossing the Sillaro River, and pulling even with the 85th Division. The 91st Division had managed to hold the attention of most of the Germans on the Livergnano Escarpment by pressuring the two natural gaps in the gigantic ledge, which towered 1,800 feet. One approach was through the town of Livergnano on Highway 65, while the other was a steep ravine more than a mile to the east near the town of Bigallo.

When the 91st Division’s attacks toward both locations commenced on October 9, a German counterattack threw the timetable of the Livergnano assault well behind. Trying to make up for lost time, one company was virtually surrounded in the town and captured almost to a man when a pair of German tanks blasted the walls of the house in which they had set up a defensive position. The 10 soldiers who managed to get back to their own lines had hidden in a pig sty. Near Bigallo, two companies of the 361st Infantry were pinned down. Reinforced, these troops finally scaled the escarpment on October 13 and took Hill 592 to outflank Livergnano, which the Germans evacuated.

With the Fifth Army now only 10 miles from Bologna, the 34th Division moved into the line in the former positions of the 85th and 91st Divisions. The 6th South African Armoured Division covered the right flank of the IV Corps during the first two weeks of October, while the 78th Division, now with the Fifth Army, continued a painstaking advance in the Santerno Valley after taking over for the 88th Division.

On the 13th, the South Africans launched their heaviest attack since the pivotal battle of El Alamein two years earlier and captured 2,200-foot Monte Stanco along with 100 German prisoners from the 94th Grenadier and the 16th SS Panzergrenadier Divisions.

The quagmire of the Romagna Plain and more than a dozen rivers that flowed through it had reduced the Eighth Army advance to a crawl. On October 1, General Leese had relinquished command of X Corps to General Richard McCreery in preparation to assume command of all British forces in Burma.

McCreery decided to move westerly into the foothills of the Apennines and sent the war-worn 5th Kresowa and 3rd Carpathian Divisions of the Polish II Corps toward Highway 9. The Poles took Montegrosso and moved on to Preddapio Nuova on the banks of the Rabbi River. On October 26, they took the town, lost it, and then took it for good the following day. Their advance in the previous five days had covered six miles.

General Keyes Digs In

During the same period, V Corps troops advanced toward Cesena and the Savio River. Attacking up Highway 9, the Carleton and York Regiments of the 3rd Infantry Brigade also headed for Cesena. The 46th Division moved into the town from the south on October 19, while the 1st Canadian Corps advanced from the southwest. As the Canadians crossed the Savio River on the night of October 21, Ernest Alvia Smith earned the Victoria Cross.

Smith, a private in the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada, was leading a PIAT antitank crew across an open field when his company was counterattacked by three tanks and at least 30 German infantrymen. Smith fired a PIAT, disabling one of the tanks, and gunned down several German soldiers who came directly at him. Smith then gave first aid to a wounded comrade and held his position until relieved.

At the end of October, Eighth Army was covering a 30-mile front from the Adriatic along the Ronco River and was utterly exhausted. McCreery had two divisions in reserve—the British 1st Armoured and the 56th—but both were terribly understrength due to a lack of replacements. The 46th Division had just left the line, and the 4th Indian Division was slated to move to Greece. Senior commanders resigned themselves to the necessity of halting. The experience had been something quite different from the prospect of tanks rolling hell for leather across the Romagna Plain.

The frustration of Fifth Army was not yet complete. On October 16, the left wing of II Corps started northward again with the 34th Division leading the way from Monte della Formiche, and the 91st Division attacking along Highway 65. Both were stymied, and General Keyes ordered them to take on an “aggressive defensive” posture.

A redoubled effort to break through to Highway 9 was undertaken by the 88th Division on October 19 and supported by concentrated naval gunfire and XXII Tactical Air Command fighter bombers flying sorties at 15-minute intervals. Monte Grande was taken easily, and the 85th Division joined the action on the 22nd.

Shrouded in fog, Hill 568 was quickly occupied. However, the fog also obscured the movement of the reinforcing 90th Panzergrenadier Division, and the 351st Regiment of the 88th Division was obliged to fight off two counterattacks. Later, Company G of the 351st took the town of Vedriano a mile and a half to the northeast and rounded up 40 prisoners. Two more companies failed to reach Vedriano when two German strongpoints took them under fire.

By the afternoon, a German emissary offered to allow Company G to retire in exchange for the 40 prisoners taken that morning. When the offer was refused, an attempt was undertaken to reinforce the men in Vedriano. An intercepted German radio message, however, noted that the town had been retaken along with 80 American prisoners.

Another attempt to take Vedriano was chewed up on the morning of the 26th as a German counterattack scooped up another company of the 351st Regiment, only one man escaping the trap.

Due to a casualty rate that could not be sustained, and supply constraints that had caused medium-caliber artillery units to ration ammunition, Clark authorized General Keyes to order his troops to dig in. In the IV Corps sector, the Brazilian Expeditionary Force’s 6th Regimental Combat Team captured Barga, while the 370th Infantry Regiment of the 92nd Division held Monte Cauala for good on October 12, after losing it twice. But the Fifth Army offensive had shot its bolt.

Beyond the Line Set at Tehran

With all its difficulties, the advance had exceeded the goal that had been set for the Allies during the Tehran Conference of the “Big Three”—British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, Soviet Premier Josef Stalin, and U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt—the previous year. The forces were indeed beyond the line running from Pisa to Rimini.

General Clark could not contain his disappointment when he reflected on the II Corps’ offensive operations: “We didn’t realize it then, but we had failed in our race to reach the Po Valley before winter set in. Our strength was not enough to get across the final barrier to which the enemy clung.”

The Germans, of course, were faced with shortages of everything as well. The command problems for Army Group C were compounded when Lemelson fell ill and was temporarily replaced by General Fridolin von Senger und Etterlin in October. Then, on the 23rd, Field Marshal Kesselring was traveling along a foggy mountain road that was crowded with military vehicles of every description. When his staff car collided with a towed piece of artillery, Kesselring was seriously injured. Transferred to a field hospital and then on to another facility in Ferrara, he did not return to command until the following February. General Gottfried von Vietinghoff took command of Army Group C, while a recovered Lemelson moved from Tenth Army to the Fourteenth, and Senger once again left the XIV Panzer Corps for the Fourteenth Army.

Taking Montefortino Twice

General Alexander considered a thrust by Eighth Army across the Adriatic to potentially outflank the Germans in northern Italy. If he could move sufficient forces into Yugoslavia to occupy the ports of Sibenik, Split, and Zadar, then in February the bulk of Eighth Army could transfer through these and quickly take Fiume and Ljubljana. The Germans would have to fight in country that finally favored the British.

However, Bologna had to be taken as a base for renewed Fifth Army operations, which Alexander expected could tie down 11 German divisions during his end run. The capture of Ravenna by the Eighth Army was also a prerequisite to the Adriatic venture.

Alexander extended the end of Allied operations in Italy one month, from November 15 to December 15, and ordered General McCreery to set a plan in motion. First, the combined weight of the 4th and 46th Divisions attacked Forli, a communications center on Route 67.

These forces were supported by a diversionary effort from elements of the 56th Division and the drive to Monte Maggiore by the Polish 5th Kresowa Division. The Poles outflanked the Germans in Forli, and they withdrew under cover of darkness on November 8. Six miles northeast of Forli, the 12th Lancers captured Coccolia, the last German strongpoint of any consequence on the Ronco River.

Next, V Corps forced the Germans from Faenza, and they withdrew across two more rivers to the banks of the Lamone. Then, the heavens opened and torrents of rain slowed progress. The Poles pressed forward with the 5th Kresowa Division, capturing Montefortino before being driven back. In relief, the 3rd Carpathian Division retook Montefortino on November 21.

A Gurkha Earns the Victoria Cross

Rifleman Thaman Gurung distinguished himself in combat during a patrol along Monte San Bartolo on November 10. A soldier of the 5th Royal Gurkha Rifles, he earned the Victoria Cross and gave his life gallantly. As Gurung and another soldier advanced along the slope, they observed a German machine-gun position preparing to open fire. Gurung charged the enemy soldiers and forced their surrender without firing a shot. As he continued to advance, he reached the summit and suppressed fire from a group of Germans threatening his section with automatic weapons and hand grenades.

Covering the withdrawal of his hard-pressed unit, Gurung remained alone and exposed as he fired into German slit trenches with his Tommy gun until his ammunition was exhausted. He then threw two grenades into enemy positions, exposed himself to machine-gun fire while obtaining two more grenades, and hurled these at the enemy. The diversion allowed most of his patrol to reach safety.

“Meanwhile,” Gurung’s Victoria Cross citation reads, “the leading section, which had remained behind to assist the withdrawal of the remainder of the platoon, was still on the summit, so Rifleman Thaman Gurung, shouting to the section to withdraw, seized a Bren gun and a number of magazines. He then, yet again, ran to the top of the hill and, although he well knew that his action meant almost certain death, stood up on the bullet-swept summit, in full view of the enemy, and opened fire at the nearest enemy position. It was not until he had emptied two complete magazines, and the remaining section was well on its way to safety, that Rifleman Thaman Gurung was killed.

“It was undoubtedly due to Rifleman Thaman Gurung’s superb gallantry and sacrifice of his life that his platoon was able to withdraw from an extremely difficult position without many more casualties than were actually incurred, and very valuable information brought back by the platoon resulted in the whole Monte San Bartolo feature being captured three days later.”

The Liberation of Yugoslavia On Hold

While Fifth Army rotated tired divisions out of the front line and welcomed additional strength to the Brazilian Expeditionary Force, along with 5,000 replacements, General Clark was making plans to resume the drive through the northern Apennines to Bologna in early December. Political and battlefield events, however, caused a change of plans and a refocusing of the Allied effort in Italy.

Alexander’s designs on a landing in Yugoslavia were laid to rest permanently when the Germans temporarily reoccupied western areas of that country. Further, Tito’s communist partisans were bolstered by the approach of the Red Army and made it clear that Allied soldiers would not be greeted with open arms on the Dalmatian coast.

Compounding the difficulties in planning the offensive, a shuffle in the high command was announced in late November to be effective the middle of December. Sir John Dill, the leader of the British military mission in far off Washington, D.C., had died unexpectedly. General Henry Maitland Wilson was promoted to field marshal and named as his replacement, setting off a chain reaction. Alexander was promoted to field marshal and elevated to command in the Mediterranean Theater, while Clark rose to the leadership of 15th Army Group, and General Lucian Truscott, former head of VI Corps, was recalled from France to take charge of the Fifth Army.

Victoria Cross at Faenza

Followed by heavy airstrikes on December 2, the 1st Canadian Corps advanced toward Ravenna against heavy opposition. With the Canadian 5th Armoured Division in the van, the corps cut Highway 16 and occupied the undefended city two days later. The Canadian 1st Infantry Division bridged the Lamone River on December 5. The Polish II Corps took the town of Montecchio west of the Lamone and anchored the left flank of the Eighth Army.

Determined to hold Faenza, Hitler allowed Vietinghoff to withdraw from threatened positions near the Lamone while General Herr’s LXXVI Panzer Corps was bolstered with the arrival of the 90th Panzergrenadier and 98th Infantry Divisions.

Fighting in the vicinity of Faenza on December 10, Lieutenant John Henry Cound Brunt performed heroically. Serving as an acting captain with the Sherwood Foresters (Notts and Derby Regiment) attached to the 6th Battalion, Lincolnshire Regiment, Brunt defended a position that was attacked at dawn by troops of the fresh 90th Panzergrenadier Division.

Brunt shot down 14 Germans with a Bren gun and covered the withdrawal of his men to safety. He then returned to his original position to help evacuate several wounded soldiers. During a second German attack that day, Brunt directed the fire of a Sherman tank from atop its hull. He then leaped from the tank and pursued small groups of enemy soldiers, inflicting numerous casualties. He was killed by mortar fire the following day and his family was later presented with his posthumous Victoria Cross.

The V Corps advanced directly on Faenza from three sides on December 14 and the Germans escaped the closing trap just ahead of the 43rd Motorized Indian Infantry Brigade, 10th Indian Division, which rolled into the town as morning broke. The V Corps’ advance then came to a halt against strong German positions and flooded fields along the Lamone. Engineers worked to repair a bridge across the river on Highway 9. Meanwhile, the 1st Canadian Corps had three bridgeheads across the Lamone by December 12 and forced the Germans back to yet another river line, at the Senio, five miles to the west.

At this point, rather than giving the go ahead to the Fifth Army thrust toward Bologna, Alexander ordered a postponement. According to the official U.S. Army history, “The offensive that had been under way since August on the Eighth Army’s front and since September on the Fifth’s had left the troops near exhaustion by the beginning of December. Faced with the need to rest the weary divisions, Alexander had no choice but to call the offensive to a halt.”

Operation Winter Thunderstorm

In mid-December, word of a major German offensive against the Allied armies in France, Belgium, and Luxembourg reached the Italian front. What came to be known as the Battle of the Bulge was raging, and General Truscott, newly in command of the Fifth Army, redeployed troops to bolster the untried soldiers of the Brazilian Expeditionary Force and the 92nd Division, which held the area near the Ligurian coast north of Leghorn six miles inland to the valley of the Serchio River. Truscott reasoned that any German counterattack would likely be aimed at the Fifth Army’s major port of entry.

The 92nd Division had already been the subject of some controversy before its arrival in Italy. Composed of black soldiers and primarily white officers, the unit was disadvantaged from the start. Its troops were from poorer educational and socioeconomic backgrounds, and white officers shunned assignment to it. Only one regiment, the 370th, had limited combat experience.

On December 26, Truscott’s worries were confirmed when a German attack, codenamed Operation Wintergewitter, or Winter Thunderstorm, descended on the 92nd’s positions. Elements of the German 285th and 286th Infantry Regiments, the 4th Alpine Battalion, and the Mittenwald Battalion advanced up to five miles, capturing several villages and putting many soldiers of the 92nd Division to flight.

The 366th Regiment of the 92nd, with the exception of a few pockets of resistance, gave way, opening a 500-yard gap in the line. By the 27th, the Germans had advanced beyond the town of Barga and begun to pull back, their mission completed. Two brigades of the 8th Indian Division were moved forward on the 26th and retook the lost ground against light opposition.

After the Germans had withdrawn, the decision was made to postpone a Fifth Army drive to Bologna until the spring of 1945. This was the fourth and final postponement of the offensive, and it was due in part to the tactical success of Operation Winter Thunderstorm.

With the Eighth Army at the Senio River, Fifth Army was roughly where it had been at the end of October and would spend another miserable winter in the mountains amid snow and ice. Offensive operations ceased. It was time for the Allies to rest and replenish as much as possible. The final offensive in Italy would come soon.

Very detailed article a good read

My dad was a truck driver in the US Army during WWII. He landed in North Africa and from there he was in 2 campaigns in Italy: Rome-Arno and the Naples-Foggia Campaign. His tour ended after the US entered France. He served 3 1/2years. Thank you so much for the map and also including the African American soldiers from the 92nd Division “the Buffalo Soldiers”. Great job!! (My mom’s dad served in WWl. I have a beautiful picture of him in uniform.)