By Neil Taylor

In the six weeks since Britain’s formal declaration of war against Germany on September 3, 1939, the Royal Air Force (RAF) pilots of No. 41 Squadron based at Catterick had flown numerous air patrols over the northeastern coast of England, all to no avail; they had sighted no enemy aircraft. When B Flight’s Green Section—flown by Flying Officer Howard Peter “Cowboy” Blatchford, Flight Sergeant Edward “Shippy” Shipman, and Sergeant Pilot Albert “Bill” Harris—scrambled to investigate an incoming raid on October 17, 1939, they were less than optimistic about encountering Luftwaffe aircraft. It was only after 40 minutes of fruitless searching that Shipman spotted a solitary German bomber flying north along the English coast.

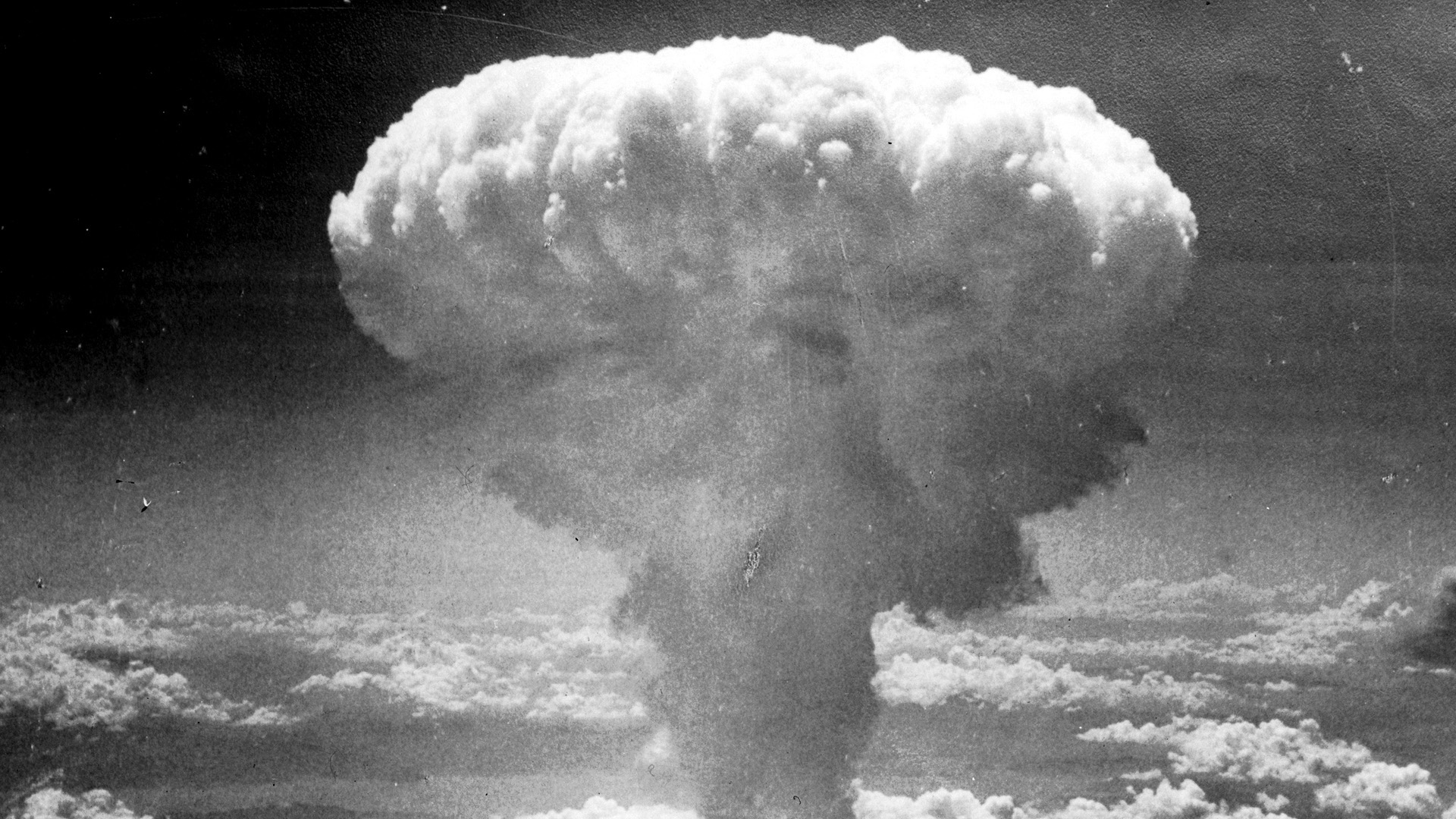

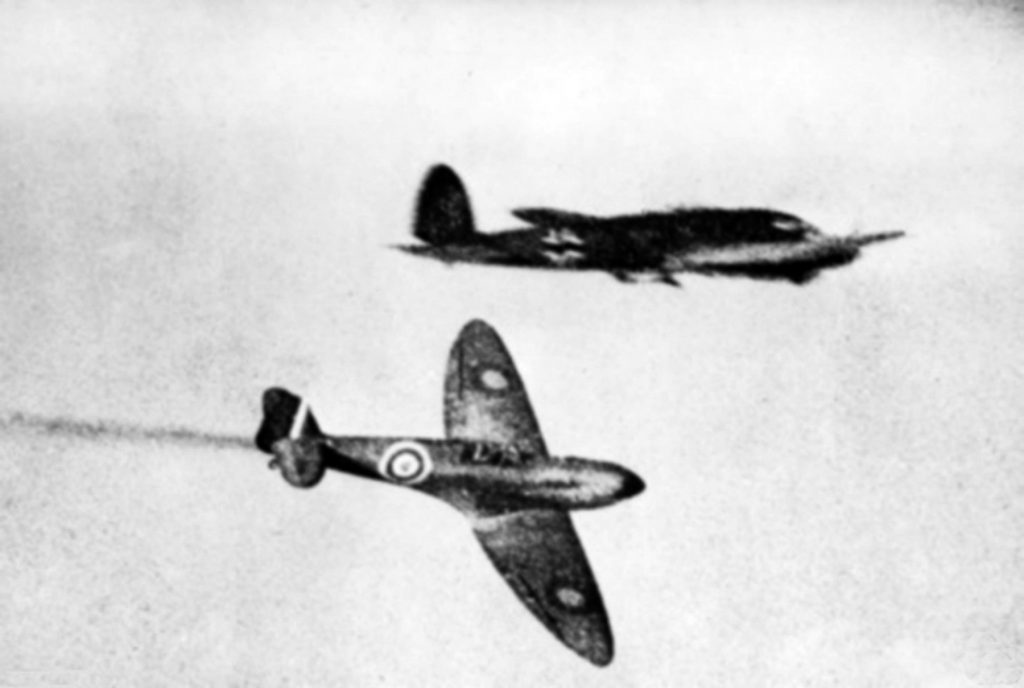

He alerted the others, dipped his wing, and dove after his prey with Blatchford and Harris in close pursuit. The German bomber, a Heinkel He-111, caught sight of its attackers and dove for the safety of the North Sea’s wave tops. Its dorsal turret gunner fired frantically at Shipman’s rapidly closing Supermarine Spitfire, forcing Shipman to break off his attack. Circling tightly, Shipman came in from dead astern of the fleeing Heinkel and opened fire, striking home across the breadth of the bomber’s fuselage. The dorsal gunner ceased firing, and both engines began to smoke.

Out of ammunition, Shipman broke away before noticing glycol drenching his left leg. Assuming his cooling system had been hit, he turned back for Catterick. Harris then moved in for an attack but was forced to abort when one of his guns jammed.

The last pilot with a chance to stop the Heinkel was Flying Officer Blatchford. Closing from astern, he triggered his first burst at 400 yards, scoring several hits before being forced to pull up suddenly to avoid a collision. Facing no return fire from either the ventral or dorsal gun positions, Blatchford lined up carefully for a final attack from astern. At a range of 400 yards, he poured his remaining ammunition into the bomber, then pulled away to allow Harris, whose guns were now operational, to make his second attack.

Harris continued to relentlessly pound the defenseless and rapidly descending Heinkel before it finally succumbed, ditching in the water about 20 miles from Whitby. As Blatchford and Harris circled above, two men later identified as pilot Oberfeldwebel Eugen Lange and radio operator Unteroffizier Bernhard Hochstuhl scrambled into a dinghy before the bomber disappeared below the waves. Blatchford and Harris radioed in the men’s location so a rescue launch could find them, and then they headed back to Catterick. While the rescue launch never located the dinghy, the two men eventually drifted ashore after spending two days in bitterly cold weather and high seas. When apprehended by local police, Lange and Hochstuhl became the first prisoners of war captured on English soil during World War II.

The reception Blatchford, Harris, and Shipman received at Catterick was decidedly different. Upon their landing, a bottle of champagne was produced to celebrate No. 41 Squadron’s first aerial victory of the war. For Howard Blatchford, the occasion was especially rewarding since it marked the first enemy aircraft downed by a Canadian in World War II. It was an auspicious beginning to what would be a remarkable, albeit short, aerial career.

Born on February 25, 1912, in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada, the young Howard Blatchford had an intense interest in aviation. With his father’s support, he began flying lessons at the Edmonton and Northern Aero Club under the tutelage of Captain Maurice Burbridge, an instructor and former bomber pilot with the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) during World War I.

In 1930, Howard Blatchford obtained his private pilot’s license and sought to enlist in the Royal Canadian Air Force. Unable to meet the enlistment requirement of a university degree, Howard left for Britain to pursue his aviation dreams.

After his arrival in December 1935, Howard obtained a short-service commission with the RAF in late January 1936. Blatchford’s first posting was to No. 41 Squadron on January 10, 1937 at RAF Catterick.

When Blatchford arrived at No. 41 Squadron, the unit was still flying the Hawker Demon, a two-seater fighter variant of the Hart light bomber. Blatchford and his squadron mates were much more impressed when they started receiving the Supermarine Spitfire I in late December 1938, making No. 41 Squadron the third RAF squadron to receive the nimble fighter.

By 1939, war seemed inevitable, and training proceeded at a hectic pace as the pilots and ground crew learned the unique characteristics of the formidable Spitfire. For Howard Peter Blatchford, there was one particularly emphatic learning moment on June 8, when he forgot to pump down his undercarriage and performed a wheels-up landing in his Spitfire, skidding across the runway on his wings and fuselage. While the aircraft had to be written off, Blatchford luckily avoided any disciplinary action.

By now Howard had earned the nickname “Cowboy.” Its origin is unsure—some claim it was an acknowledgment of Blatchford’s western Canadian roots; others suggest it might have been derived from his love for hillbilly music. Regardless of its origin, the moniker fit Blatchford well.

When German panzers rolled into Poland on September 1, 1939, the pilots of No. 41 Squadron knew everything had changed. Cowboy Blatchford remembered how he felt when the United Kingdom declared war on Nazi Germany two days later. “I shall never forget the scene in the mess at Catterick as we sat and listened to [Prime Minister Neville] Chamberlain’s announcement of war over the radio, and the strange silence that followed, as we tried to adjust our minds to the fact. We just looked at one another incredulously, and I remember thinking: ‘This is goodbye to the old carefree life.’ How true that was!”

For the first weeks of the war, Blatchford and his squadron mates practiced their interception techniques and flew defensive patrols across northeast England. No. 41 Squadron’s patrols took on greater urgency as the weather deteriorated, plunging Britain into one of its worst winters on record. Doggedly, the squadron soldiered on, providing convoy escort and standing air patrols, but neither Blatchford nor any of his squadron mates were successful in engaging the enemy. Anxious to experience more action, Blatchford was relieved when he was posted to No. 212 Squadron.

This new squadron was a unique group, a strategic photoreconnaissance unit that owed its existence to Wing Commander Sidney Cotton, an Australian with a keen sense for adventure and intrigue. When Cowboy Blatchford joined No. 212 Squadron on April 20, 1940, it was based at Seclin, functioning as a detachment of the Photographic Development Unit or PDU. While Heston, a civilian airport just outside London, served as the PDU’s home base, Spitfires were posted not only to Seclin, but also to Nancy in northeastern France. When the Germans swept into the Low Countries on May 10, they bombed No. 212 Squadron’s bases at Lille and Nancy, forcing the unit to move to Coulommiers and Meaux to continue operations.

The squadron’s Spitfires and other aircraft flew operations non-stop, heading aloft as soon as they were serviceable from the previous mission. They sought out troop concentrations, transportation corridors, and undamaged bridges that could become the focus of Allied bomber attacks.

The Belgian Army capitulated on May 28, and by June 4, the British Expeditionary Force and elements of the French First Army had executed a desperate evacuation from Dunkirk. As the Germans advanced southward, No. 212 Squadron retreated to Orleans-Bricy.

By June 14, the German Army had marched into Paris, and Wing Commander Cotton decided No. 212 Squadron needed to move again. He sent his Spitfires back to Heston, and the rest of the squadron was ordered south to Poitiers. Caught in the confusion of the overall Allied retreat, Cowboy Blatchford soon found himself stranded in Orleans with spearheads of the German Army only 15 miles away and closing fast.

During his desperate search for a means of escape he recalled, “Luckily, I found a Tiger Moth that nobody seemed to own, so I packed in a ground crew chap who had also been left behind, and we flew to Poitiers, one hour away.”

Blatchford remained in Poitiers for three days until another Tiger Moth landed at the airfield, piloted by a New Zealander, Flight Lt. Earnley Clark. Blatchford and Clark chose to fly their Tiger Moths back to England via the Channel Islands, securing 20-gallon barrels of fuel to each of their aircraft and took off. Landing at Nantes to refuel, they were surprised to find a field full of aircraft. When told they were to be destroyed, Blatchford pointed at his Tiger Moth and said, “Okay, then burn this thing. I’ll have one of those,” a Fairey Battle bomber. “And then I flew her home to Heston Aerodrome.”

While everyone made it back safely, it had been a narrowly won race to flee the continent. Changes were immediately instituted: Wing Commander Cotton was relieved of command due to a longstanding dispute with the Air Ministry, and No. 212 Squadron and the Photographic Development Unit were combined to form the Photographic Reconnaissance Unit (PRU).

On September 3, 1940, Cowboy Blatchford was promoted to flight lieutenant, but his days with the PRU at Heston and St. Eval were numbered. On September 30, he was transferred to No. 17 Squadron based at Debden, England, a sector station for Group 11 Fighter Command located south of Cambridge. This squadron was still flying Hurricanes, and although his stay was brief, it was memorable.

On the morning of October 2, 1940, Flight Lt. Blatchford led a group of four Hurricanes aloft in pursuit of a German bomber that had just bombed Colchester. They were flying an intercept course when Blatchford spotted the intruder, a Dornier Do-17, seeking cover in a cloud bank. Blatchford peeled off in pursuit, followed closely by the remainder of the flight. He closed to 250 yards and triggered a burst of gunfire that crippled the Dornier’s left engine.

Cowboy broke away to commence another pass while a second Hurricane pressed home an attack from the rear. The Dornier was struggling to reach the safety of the clouds when Blatchford made his second pass, closing to only 20 yards while continuing to rake his opponent with gunfire. Fires took hold in the rear fuselage and near the left wing root before the other Hurricane renewed its attack, forcing the German pilot, Oberleutnant Hans Langer, to attempt a crash landing. Remarkably, Langer and the rest of his crew survived the crash unhurt. Meanwhile, Blatchford had turned back for Debden nearly out of fuel. When his fuel-starved engine finally died, Blatchford made a successful forced landing near Pulham. He was awarded half a victory for the destruction of the Do-17.

Two days later, Flight Lt. Blatchford was posted to No. 257 Squadron, flying Hurricanes out of RAF Martlesham Heath east of Ipswich. He was specifically requested by the squadron commander, the famed Battle of Britain ace Robert Stanford Tuck, who was seeking an experienced flyer to become a flight commander. The two men became fast friends.

Squadron Leader Tuck saw great potential in Blatchford, mentoring him in the finer points of aerial combat, while Blatchford’s easygoing manner seemed to “humanize” the consummate-professional Tuck. Together, they were a formidable duo in any dogfight.

October 1940 found No. 257 Squadron fully engaged, even though the Luftwaffe had primarily switched to night attacks. The squadron had moved to North Weald near Epping, Essex, and the airfield became the target of an October 29, 1940, raid by a swarm of Messerschmitt Me-109s under the command of Major Adolf Galland. As the German fighters roared over the airfield, a dozen Hurricanes were preparing to take off. Squadron Leader Tuck was leading Yellow Section aloft when a bomb exploded at the end of the runway, flipping Sergeant Alexander “Tubby” Girwood’s Hurricane over Tuck’s before crashing on its belly. While Tuck’s aircraft was not touched, Girwood’s erupted in flames, trapping him inside. Unable to escape the inferno, Sergeant Girwood was burned alive as the fuel tanks and onboard ammunition exploded.

As the carnage spread across the airfield, Hurricanes and Me-109s tangled overhead in a deadly dogfight. Three of No. 257 Squadron’s Hurricanes were now airborne, flown by Flight Lt. Blatchford, Sergeant R.C. Nutter, and Pilot Officer Franciszek Surma, a Pole. Blatchford found himself a target in a head-on attack by Hauptmann Gerhard Schopfel, Gruppenkommandeur of Gruppe III, Jagdgeschwader 26. Blatchford’s Hurricane was peppered with shells, piercing the oil tank and damaging the tail. One cannon shell ripped through the fuselage and passed between Blatchford’s knees. Just when it appeared that Blatchford was doomed, Sergeant Nutter intervened and drove the German off. Blatchford crash-landed his damaged fighter back at North Weald.

Schopfel was not finished. While Surma had avoided a bomb blast on takeoff, he was soon in Schopfel’s sights. A cannon shell exploded in his cockpit, and with the controls dead and the cockpit filling with smoke, Surma opened the canopy and bailed out. His parachute successfully deployed, but he drifted into an elm tree behind the White Hart pub in Moreton.

Two weeks later, Cowboy Blatchford got some revenge for the North Weald raid, but it was at the expense of Italians, not Germans. In the early afternoon of November 11, 1940, nine Hurricanes from No. 257 Squadron were scrambled along with others from No. 17 and No. 46 Squadrons to intercept an incoming flight of enemy bombers. With Squadron Leader Tuck grounded due to a painful eardrum, Cowboy Blatchford led No. 257 Squadron into battle.

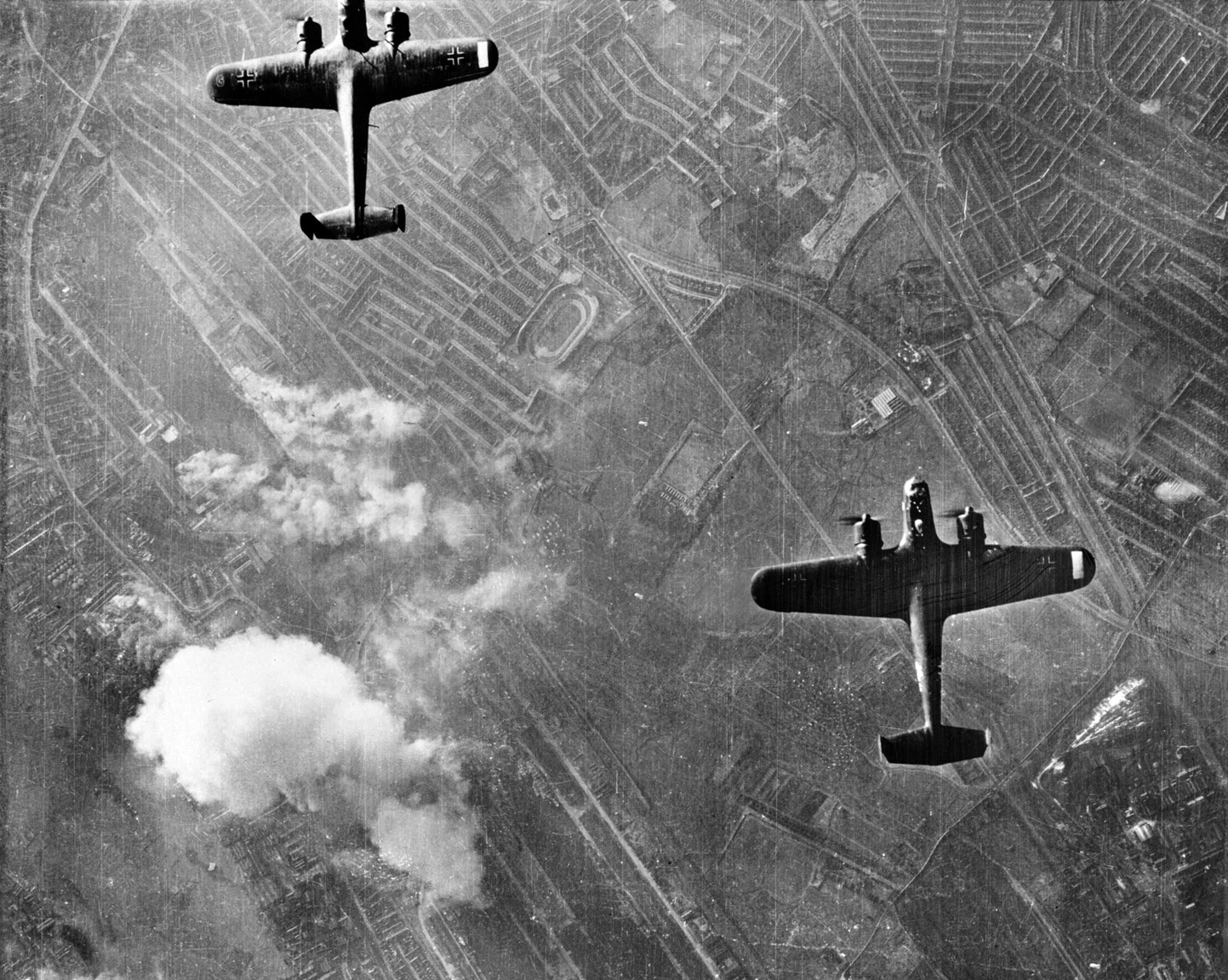

Vectored out to sea at the mouth of the River Thames, Blatchford spotted what he called the “funniest-looking kits you ever saw” and took his squadron down to investigate. It was a flight of bombers belonging to the Corpo Aereo Italiano, making a rare appearance by the Italian Air Force during the Battle of Britain. Nine Fiat BR.20 Cicogna twin-engine bombers were being loosely escorted by two formations of Fiat CR.42 Falco biplane fighters, about 40 in total.

While No. 46 Squadron, led by another Canadian, Squadron Leader Lionel Gaunce, kept the fighters at bay, Blatchford’s group tore into the bombers. According to Blatchford, “I selected the rear starboard bomber and opened fire with a beam attack, firing a four second burst” before plunging past the enemy. It was later confirmed that a Hurricane from No. 46 Squadron dealt the final blow to this bomber (earning Blatchford a shared kill). Meanwhile, Blatchford passed over to the port side of the formation and staged a quarter attack on the rearmost bomber. “Owing to my speed, I repeated this attack on both occasions with a two-second burst. The bomber then looped violently and went into a vertical dive towards the sea and disintegrated before hitting the water.”

Another fighter swept in to engage Cowboy, and they entered into a series of tight turns, Blatchford firing short bursts at his Italian opponent when the opportunity presented itself. Finally, his ammunition expended, he pulled in close behind the CR.42 and attempted to ram it. The Hurricane’s propeller chewed through the main top wing, and the Italian aircraft immediately began losing altitude. Blatchford was in trouble himself, out of ammunition and now flying a badly mangled airplane, so he turned for home. Blatchford repeated the trick on another group of CR.42s, and they, too, broke off their attack. Upon landing at North Weald, Blatchford discovered that “nine inches of one of the blades of my propeller was found to be splashed with blood.”

The final count for the day’s combat was 12 Italian aircraft shot down without a single British loss. Cowboy Blatchford’s actions had accounted for the destruction of one BR.20, a shared kill of another, and the damaging of two CR.42s.

Six days later, Flight Lt. Blatchford scored again as his flight of Hurricanes happened upon a pack of Me-109s southeast of Harwich. According to Blatchford, “I led the squadron up towards the sun to cut off the 109s who were on my starboard side. While we were converging, the 109s realized we held an advantage, and they were forced to turn left-handed towards us, forcing us to attack head-on.”

For Blatchford, it was a terrifying experience, but he recalled that as they drew closer, “I opened fire on the leader at about 300 yards with a four-second burst. As he went over the top, I gave a full deflection shot and I then did a right-hand turn and saw the 109 in front of me streaming profuse black smoke. I engaged the 109 again from astern. He continued to dive, and I followed behind and above. He appeared to flatten out, so I put the finishing touches on him. The enemy aircraft did a cartwheel and the pilot was jettisoned into the sea.”

On January 26, 1941, Cowboy Blatchford and Stanford Tuck flew to Bircham Newton, where, in an investiture ceremony held by His Majesty King George VI, Blatchford received the Distinguished Flying Cross for his heroic actions against the Italians, while Tuck was awarded the Distinguished Service Order and a bar to his DFC. Blatchford’s citation read, “In November 1940, this officer was the leader of a squadron which destroyed eight and damaged a further five enemy aircraft in one day. In the course of the combat, he rammed and damaged a hostile fighter when his ammunition was expended, and then made two determined head-on feint attacks on enemy fighters which drove them off. He has shown magnificent leadership and outstanding courage.”

Toward the end of February 1941, No. 257 Squadron began converting to the Hurricane IIC, which was armed with four 20mm Hispano-Suiza cannon. Now Blatchford, Tuck, and the other pilots had a machine with the firepower to combat the 20mm cannon of the Me-109s. Tuck decided it was time to take the battle to the Germans, and he drafted Cowboy Blatchford to conduct lightning raids into France and the Low Countries. Air Marshal Sir William Sholto Douglas, commander-in-chief of Fighter Command authorized a trial attack to test their proposal.

On March 2, 1941, Stanford Tuck and Cowboy Blatchford took to the air, their objective a triangular patch of Holland containing several Luftwaffe airfields, railway yards, and other targets of opportunity. The flight across the English Channel was uneventful, and when they finally popped out of the clouds, they found several airfields packed with German fighters. At one airfield, the two men flew directly at the control tower, their Hurricanes barely five feet off the ground. At the last moment, they broke sharply away, but not before seeing the startled expressions on the faces of the German controllers. Satisfied that they had proved the feasibility of their plan, Tuck and Blatchford turned for home.

The operation was a complete success, and as Tuck reported later, they had proved that German radar had difficulty identifying their low-level approaches. Sholto Douglas sanctioned more fighter sweeps over the continent, ranging from large-formation intrusions—called “Rangers”—to sorties by one or two aircraft, called “Rhubarbs.”

Meanwhile, the notoriously fickle English winter weather once again hampered patrols. Cowboy Blatchford did not record his first aerial success in 1941 until March 19, downing a a Junkers Ju-88. As winter faded into spring, Blatchford found himself involved in night patrols. Blatchford was one of the few daytime fighter pilots to succeed in downing an enemy aircraft at night. It was the night of May 11, 1941, when Cowboy Blatchford and Squadron Leader Tuck were patrolling separate portions of the English coast. Suddenly, Tuck excitedly exclaimed, “Listen to this!” as his cannon and machine guns erupted into action blasting the German bomber.

Blatchford chuckled, but scant minutes later, he spotted another He-111 directly above him. He yelled into his radio transmitter, “Now you listen!” as he opened fire with his own cannon. As it began to lose altitude, Blatchford continued to pour shells into the German aircraft, and fire engulfed the starboard engine. Both men had scored in a matter of minutes, and their cockpit exchange was a source of continued amusement whenever the two men got together.

When Stanford Tuck was promoted to wing commander (flying) in July 1941 and given command of the Duxford Wing, Cowboy Blatchford was promoted to squadron leader and assumed command of No. 257 Squadron. On September 8, 1941, Blatchford was promoted again, this time to wing commander (flying) of the Digby Wing. At that time, the wing was stationed at RAF Digby in Lincolnshire and consisted of Royal Canadian Air Force No. 401, 411, and 412 Squadrons plus RAF No. 266 Squadron. An all-Spitfire wing, the Digby crew participated in countless sweeps and bomber-escort operations across France and the Low Countries.

Tuck and Cowboy Blatchford kept in close contact, often visiting one another. On January 28, 1942 Blatchford flew down to Biggin Hill to have lunch with his mentor and friend. Over beers in the mess, Tuck tried to talk Cowboy into taking part in a Rhubarb operation targeting the alcohol distillery at Hesdin, France. The weather was rapidly deteriorating, and Blatchford wanted to get back to Digby before he was socked in, so he declined. Little did he know that it was the last time he would see Tuck. Less than an hour later Tuck’s Spitfire lay smoldering in a French field, brought down by antiaircraft fire. Luckily, Tuck survived the crash and became a prisoner of war. Blatchford was not to be so lucky.

Operations continued intermittently as the English winter, steeped in mist, rain, and dreary clouds, blanketed the countryside. Eventually, the weather improved, and by March, the squadrons under Blatchford’s control were making frequent trips to the continent.

On April 25, Blatchford’s squadrons were escorting a flight of Douglas Boston bombers when they flew over Abbeville, France. The response from the German fighters stationed in the area was swift. As the enemy moved in on the bombers, Blatchford and his fellow Spitfire pilots dove down to intercept. Blatchford picked one of the lead aircraft and fired two bursts into it at 250 yards, recording strikes on the fuselage. The Focke-Wulf FW-190 pilot attempted no evasive measures, so Blatchford continued to pump shells into the doomed airplane until it finally fell in flames.

As he watched the FW-190 spiral into the sea, Blatchford suddenly found himself under attack, cannon shells hitting his left aileron, right wing, and tire. His landing gear damaged, Blatchford fought to maintain lateral control. It was a near miracle that he coaxed his aircraft back to Digby, where he crash-landed and was slightly injured.

Shortly after his crash, Cowboy Blatchford was taken off operations for a period of 10 months, and during that time, he was assigned as a staff officer to one of Fighter Command’s group headquarters.

On February 5, 1943, Blatchford began his second operational tour, this time as wing commander (flying) of the Coltishall Wing based in Norfolk. The wing consisted of the experienced No. 118 Squadron and the relatively new No. 167 Squadron, both flying Spitfire VBs.

At this stage of the war, the Coltishall Wing was used primarily for the escort of British and American light and medium bombers on daylight missions over occupied Europe. “Ramrod” operations aimed to destroy targets on the ground, while “Circus” missions were intended to draw enemy fighters into action. The Lockheed Venturas and Douglas Bostons that made up the bomber force were highly vulnerable to enemy attack due to their poor speed and limited armament. To give them a fighting chance to reach their targets, the Coltishall Wing flew as high cover, ready to dive on any Luftwaffe fighters that made an appearance.

The operation flown on March 18, 1943, was a typical Ramrod mission. Twelve Venturas of No. 464 Squadron of the Royal Australian Air Force were assigned to bomb the Witol oil refinery at Maassluis, Holland. Escort was provided by No. 118 and No. 167 Squadrons, led by Wing Commander Blatchford.

No interference was experienced on the run-in to the target, and after releasing their bombs, the Venturas made a wide starboard turn to return to England, while No. 118 Squadron positioned itself above and behind the bombers. Soon, a gaggle of FW-190s appeared and streaked toward the Venturas. Blue Section of No. 118 Squadron dived on the attackers, only to be bounced by another group of Focke-Wulfs. Meanwhile, a third group of enemy aircraft closed on the bombers. Wing Commander Blatchford and Flying Officer Reyhill from No. 167 Squadron dove to intercept them.

Blatchford selected a target and closed to 200 yards before opening fire. Strikes were seen along the entire length of the FW-190’s fuselage before it rolled over on its back and went into a flat inverted spin, during which Reyhill also fired on it. Blatchford, meanwhile, closed in on the leading FW-190 and blew its wing off, forcing the enemy pilot to bail out. By this time, Blatchford and his wingman had lost the bomber formation, so they set a return course to Coltishall. All the Venturas successfully returned to base.

On April 18 Wing Commander Blatchford led 22 Spitfires from No. 118 and No. 167 Squadrons, along with eight North American P-51 Mustangs from No. 613 Squadron, as escort for a strike wing of 21 Bristol Beaufighters on an anti-shipping operation off the Dutch coast.

Allied reconnaissance aircraft had spotted a German convoy off Ijmuiden with at least one 5,000-ton freighter and four flak ships (coastal anti-aircraft patrol boats). Twelve Beaufighters were assigned to flak suppression and sported cannons, machine guns, and 250-pound bombs. The remaining nine aircraft, commonly called Torbeaus because they carried cannons and torpedoes, were to attack the merchant ships. Wing Commander Blatchford’s escorts took position slightly above and behind the attacking aircraft to prevent any enemy bounces from the rear.

When the strike force found the convoy off the island of Texel, the surprise was complete. The anti-flak Beaufighters damaged four escort ships, and the Torbeaus, singling out the largest ship in the convoy, put three torpedoes into the side of the 4,903-ton Danish Hoegh carrier, sending the ship and its load of coal to the bottom of the sea. The aerial victory had been complete and decisive: one enemy freighter sunk and four escort ships damaged without a single loss to the strike force.

On May 2, the Coltishall Wing escorted yet another flight of Venturas on an attack on the iron and steel works at Ijmuiden in Holland. The No. 118 and No. 167 Squadrons flew as close escort, while a Polish Spitfire wing provided top cover.

The outward leg of the flight was uneventful, but the formation had barely finished its bomb run and turned back toward England when a large number of FW-190s appeared. Soon, the sky was filled with twisting, diving, jinking Spitfires and Focke-Wulfs, all maneuvering to get the enemy in their sights. By the time the combatants separated, two German fighters had been knocked out of the skies and another damaged, but no Spitfires were lost. Wing Commander Blatchford was credited with one probable kill and his No. 3, Flight Lieutenant Hall, with one damaged.

The next day, May 3, 1943, the combined Coltishall Wing (Nos. 118, 167, and 504 Squadrons) was back flying close escort for the Venturas of No. 487 RNZAF Squadron and the Bostons of No. 107 Squadron. The New Zealanders were conducting a diversionary raid on a power station in Amsterdam, while the main force of Bostons was to bomb a power station and the iron and steel works in Ijmuiden. A further top cover was to be provided by additional Spitfire IX squadrons.

Unfortunately, the Spitfire IXs crossed the Dutch coast too early, alerting the German defenses, and then began running low on fuel and had to leave before the bomber force arrived. To make matters worse, the Nazi governor of Holland was on a tour of the area accompanied by a group of fighters, and other German fighter pilots were meeting in the area to discuss tactics. As a result, more than 70 FW-190s and Me-109s were mustered to greet the bombers.

Wing Commander Blatchford spotted the incoming Germans and attempted to recall the bombers, but the trap had been sprung. While FW-190s tackled the fighter escort, the Me-109s dove into the Venturas. Of the 12 bombers in the Ventura formation, two were shot down and two others severely damaged before they reached the coast. The fighters bore in relentlessly, and soon only four Venturas, including that of Squadron Leader Leonard Trent, were left to conduct their bombing runs. As they approached the target, Trent’s wingman was shot down, and then the other two Venturas were also destroyed.

Alone, Trent and his crew pressed home the attack, but they had no sooner released their bombs than they were hit by flak. Trent and his navigator managed to bail out, but two others perished in the crash. Trent served out the remainder of the war as a POW. Upon his liberation, he was awarded the Victoria Cross for valor during the attack.

The Spitfires and Bostons had also had a tough time of it. Blatchford’s group had been cut off from the bombers by the attack of more than 20 FW-190s. A swirling dogfight ensued, with the Coltishall Wing intent on protecting the Bostons, while the Focke-Wulfs pounced on any fighter they could find. The wing was successful—to a degree. Only one Boston was lost, while three FW-190s were destroyed, and only one Spitfire failed to return.

Unfortunately, that Spitfire was flown by Wing Commander Cowboy Blatchford.

It is believed that Leutnant Hans Ehlers of 6th Gruppe, Jagdgeschwader 1, had badly damaged Blatchford’s Spitfire, forcing it down into the English Channel 40 miles off Mundesley. It was Ehlers’ 19th aerial victory, and he eventually went on to record 55 victories before being shot down and killed on December 27, 1944, while tangling with P-51 Mustangs of the 364th Fighter Group of the U.S. Army Air Forces.

A motor launch was dispatched to search for Blatchford, but there was no sign of him or his Spitfire. Cowboy was officially classified as missing after air operations over enemy territory, and back in Edmonton, his mother anxiously awaited news that he had been found or, at worst, was a prisoner. No such notification was forthcoming, and it became clear that Blatchford, one of the first Canadian wing commanders in World War II, a courageous pilot with six confirmed victories and three probables along with 4½ damaged enemy aircraft to his credit, was dead at age 31.

Today, Howard Peter Blatchford’s supreme sacrifice is acknowledged on Panel 118 of the Runnymede Memorial in Surrey, England, a monument honoring more than 20,400 British and Commonwealth airmen and women from World War II who have no known grave.

Author Neil Taylor has written for WWII History on a variety of topics. He resides in Edmonton, Alberta, Canada.