By Al Hemingway

To say that Caius Julius Caesar was one of the most influential men in world history is still something of an understatement. Undoubtedly the most famous Roman of all, he played a key role in converting the Roman republic into a fledgling empire when he crossed the Rubicon in 49 bc and ignited a bloody civil war. His countless military triumphs and political victories ultimately catapulted him to the post of virtual dictator of Rome, but also led eventually to his death.

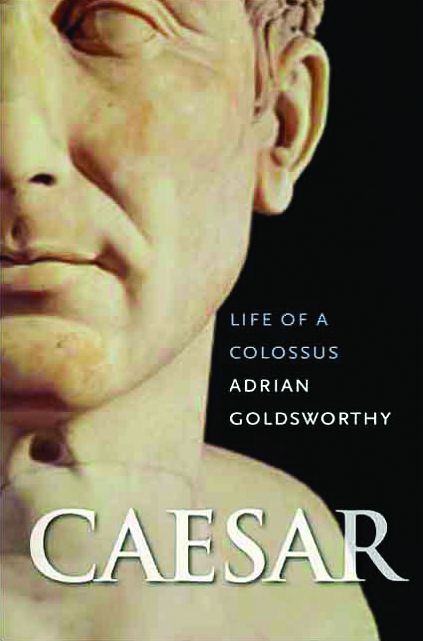

In his new book, Caesar: Life of a Colossus (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2006, 581 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $35.00, hardcover), historian Adrian Goldsworthy closely examines the life of the man who at one time or another ruled over most of the known world. Caesar was born in 100 bc to an aristocratic family that was active in politics in the Roman republic. Caesar’s father was a praetorian, an elected official who ruled lesser provinces, while his mother’s family boasted several prominent consuls, important senior positions in the Roman army.

In his new book, Caesar: Life of a Colossus (Yale University Press, New Haven, CT, 2006, 581 pp., illustrations, index, notes, $35.00, hardcover), historian Adrian Goldsworthy closely examines the life of the man who at one time or another ruled over most of the known world. Caesar was born in 100 bc to an aristocratic family that was active in politics in the Roman republic. Caesar’s father was a praetorian, an elected official who ruled lesser provinces, while his mother’s family boasted several prominent consuls, important senior positions in the Roman army.

After the premature death of his father, Caesar became head of the household at the tender age of 16. He quickly demonstrated loyalty and courage by defying the strongman Sulla after an uprising that left him in power, by refusing to divorce his wife and marry one of the new ruler’s female choices. Fearing for his life, Caesar fled Rome.

Upon Sulla’s death, Caesar returned home and began his meteoric rise to fame amid the tumultuous backdrop of the times in which he lived. Goldsworthy describes well how he manipulated Rome’s politicians and, in some cases, even seduced their wives for political favors. The author also gives detailed accounts of Caesar’s numerous military campaigns, which eventually expanded the Roman Empire from the Atlantic Ocean to Africa and the Middle East. Caesar’s stunning victory at the Battle of Zela in Asia Minor in 47 bc was so overwhelming that he uttered, all too accurately, his now-famous words: “Veni, vidi, vici [I came, I saw, I conquered].”

Goldsworthy gives us a glimpse of Caesar’s personal life as well. He was very family-oriented despite his legendary affairs. His daughter’s sudden death left him grief-stricken, as did the passing of his mother. As the titles and laurels bestowed upon Caesar increased, so did the number of his enemies, including one of his closest associates, Marcus Junius Brutus. In 44 bc, a plot was hatched to assassinate Caesar after Rome’s aristocratic clans feared that he had acquired too much power. Luring him to the Senate under false pretenses, as many as 60 men fell upon the emperor, stabbing him to death on the lower steps of the portico. His famous final words were “Et tu Brute [You also, Brutus].” Caesar’s death initiated a long and violent civil war, which eventually resulted in Caesar’s nephew Octavian rising to power as the first Roman emperor, Augustus.

Since his death, the legend of Caesar has not diminished. As Goldsworthy writes, “Whatever the rights and wrongs of his actions, it is hard to imagine that in any way his life could have been more dramatic.”

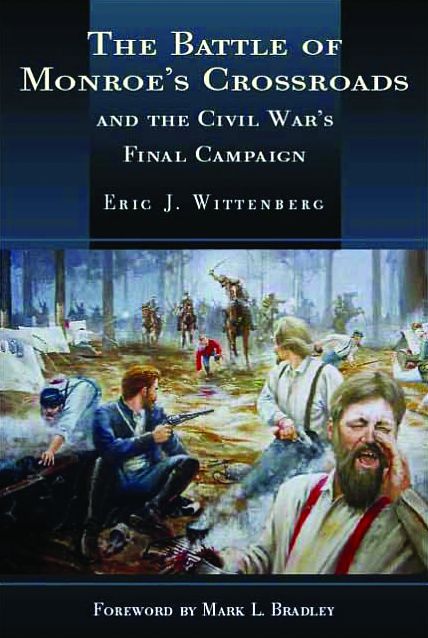

The Battle of Monroe’s Crossroads and the Civil War’s Final Campaign by Eric J. Wittenberg, Savas Beatie, New York, 2006, 336 pp., illustrations, notes, index, $32.95, hardcover.

In early 1865, much attention was focused on General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia, which was desperately attempting to flee the grasp of Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s Army of the Potomac in the waning days of the Civil War. Scant attention, however, was paid—then or later—to the bloody campaign being waged in North Carolina, where the weary butternuts of General Joseph E. Johnston’s “patchwork of units” were attempting no less desperately to block Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s surging forces from entering the Tarheel State and linking up eventually with Grant in Virginia.

At a remote intersection called Monroe’s Crossroads, one of the largest and most significant cavalry battles of the war was fought. There, Lt. Gen. Wade Hampton’s gray riders surprised the Federal cavalry of Maj. Gen. Judson Kilpatrick on March 10, 1865, and initially drove them completely from the battlefield. Kilpatrick himself fled the scene wearing only his nightshirt and escaped into a swamp.

Kilpatrick, dubbed “Kill Cavalry” by his men, had failed to put out pickets and sentries, allowing Hampton’s horsemen to sneak up on the Federals while they slept. Despite these grievous errors, Kilpatrick managed to rally his men and launch a counterattack that turned the tide and pushed the Confederates from the camp.

As historian Eric J. Wittenberg points out, although the Confederates fled the scene, they did manage to halt the bluecoats long enough to allow Lt. Gen. William J. Hardee’s troops to escape from Fayetteville and avoid being destroyed by Sherman’s massive army. The author does an effective job of bringing the battle to life with numerous firsthand accounts of the soldiers in- volved in the action, much of which wasclose- quarter combat with sabers, pistols and even hand-to-hand fighting.

Included in the book are 29 maps that allow the reader to follow the events as they unfolded over 140 years ago. Another interesting facet of the book touches upon the mysterious woman who accompanied Kilpatrick on the campaign and later was abandoned rather ungallantly when he scampered nearly nakedfrom the Monroe house to avoid capture.

Wittenberg has delivered a very readable and captivating story of a neglected action of the Civil War. Monroe’s Crossroads is a battle that has long been overlooked, but one that should be remembered, if for nothing else, for the valor and sacrifice of the men involved on both sides.

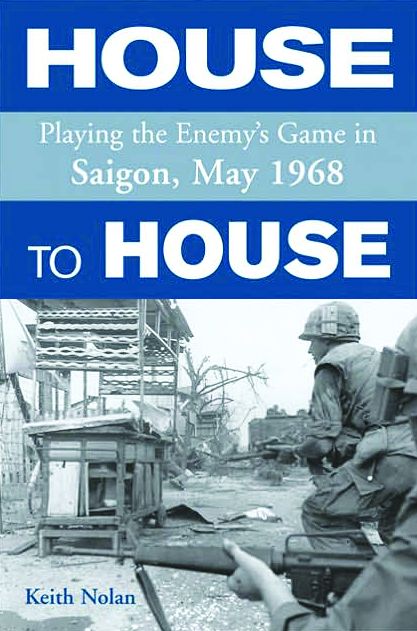

House to House: Playing the Enemy’s Game in Saigon, May 1968 by Keith Nolan, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2006, 368 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

House to House: Playing the Enemy’s Game in Saigon, May 1968 by Keith Nolan, Zenith Press, St. Paul, MN, 2006, 368 pp., illustrations, index, $24.95, hardcover.

When it comes to writing about ground combat during the Vietnam War, author Keith Nolan has few equals. His eleventh book deals with the period following the disastrous military defeat the Communists suffered during the 1968 Tet Offensive. Although Hanoi knew that it could not win on the battlefield, Ho Chi Minh and his followers realized that their “mini-Tet” would create psychological hardships and dissension back in the United States.

South Vietnam’s capital city of Saigon was the main objective of the North Vietnamese forces. Communist forces infiltrated the Cholon area of the city and the suburbs of District 8. Bloody house-to-house combat followed for two weeks with elements of the U. S. Army’s 9th Infantry Division doing battle with an unseen enemy that erected bunkers and used dwellings to conceal snipers and spring ambushes on the advancing soldiers attempting to oust them from Saigon.

Once again Nolan has given readers a gutsy look at the ferocious combat experienced by the “grunts” involved in the unenviable task of ejecting a tenacious foe from an urban area. Ironically, a very similar war is being waged today in Iraq, making Nolan’s book all the more timely. Whether it is in World War II, Vietnam, or Iraq, house-to-house fighting remains an infantryman’s worst nightmare.

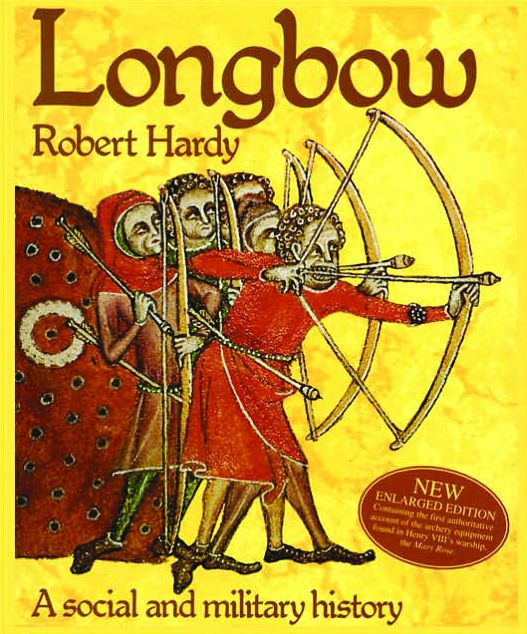

Longbow: A Social and Military History by Robert Hardy, Sutton Publishing, 2006, 244 pp., illustrations, index, softcover.

Longbow: A Social and Military History by Robert Hardy, Sutton Publishing, 2006, 244 pp., illustrations, index, softcover.

British actor and archery enthusiast Robert Hardy has penned a comprehensive book dealing with the history of the longbow, from its earliest beginnings 8,000 years ago to the modern archery tournaments around the world today. Hardy describes in detail the use of the longbow in English military history and how it was decisive during the Battles of Crécy, Poitiers, and Agincourt. Soon the weapon was an important arm of the English army, and its archers were justly feared as the deadliest when it came to lethal accuracy.

The author devotes an entire chapter to the construction of the longbow, including materials used and how the weapon is carefully manufactured. Commonly asked questions are also answered on the use and care of the bow as well. The flight of the arrow and the style of the target are also mentioned and addressed.

Anyone involved in the sport of archery or hunting with a bow should consider getting a copy of Hardy’s book. It could prove invaluable to those individuals already actively involved, as well as budding aficionados just starting out in the sport.

The Detonators: The Secret Plot to Destroy America and an Epic Hunt for Justice by Chad Millman, Little, Brown and Co., 330 pp., illustrations, index, $24.99. hardcover.

The Detonators: The Secret Plot to Destroy America and an Epic Hunt for Justice by Chad Millman, Little, Brown and Co., 330 pp., illustrations, index, $24.99. hardcover.

In the predawn hours of July 30, 1916, citizens of Jersey City, New Jersey, were suddenly awakened by an ear-shattering blast that registered 5.5 on the Richter scale. Windows were blown apart miles away, the earth trembled as far away as Maryland, and a 10-week-old baby was thrown from its crib. Accounts of fatalities vary but it is certain that three people were killed and scores wounded. The explosion was at the ammunition depot on Black Tom Island, a small piece of land situated in New York Harbor. Was the huge discharge a result of negligence on the part of workers at the site? Or was sabotage involved?

Writer Chad Millman attempts to answer these questions in his new book, taking the reader to the shadowy world of espionage around the globe in an attempt to sort out the characters involved in one of the most treacherous acts ever perpetrated on American soil.

Several years after the explosion at Black Tom Island, the Lehigh Valley Railroad presented its case before the German-American Mixed Claims Commission. They cited the 1921 Treaty of Berlin between Germany and the United States as grounds to bring suit against German saboteurs who they felt had perpetrated the heinous act. The court battle waged for years until finally in 1939, on the eve of World War II in Europe, the German government was forced to pay $50 million to all involved in the lawsuit.

Millman’s account is an absorbing slice of history—even more so in light of the events of September 11, 2001.

Best Little Stories of the Blue and Gray with “General’s Wives” by C. Brian Kelly and Ingrid Smyer-Kelly, Cumberland House, Nashville, TN, 2006, 352 pp., illustrations, index, $16.95, softcover.

Best Little Stories of the Blue and Gray with “General’s Wives” by C. Brian Kelly and Ingrid Smyer-Kelly, Cumberland House, Nashville, TN, 2006, 352 pp., illustrations, index, $16.95, softcover.

The husband and wife writing team of C. Brian Kelly and Ingrid Smyer-Kelly has written another gem in their “Best Little” series dealing with offbeat stories from the Civil War. This one is chock-full of interesting vignettes from that tumultuous period in our nation’s history.

Their book is divided into chronological order, from the beginnings of the conflict to Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House. The short stories are truly fascinating. One such tale involves Daniel Emmett, a songwriter for a traveling show called Bryant’s Minstrels. In 1859, Emmett was approached to pen a new ditty for a performance scheduled for the following Monday. He soon had the music and began the song with the line, “I wish I was in Dixie.” These words did not profess a yearning for his southern home (Emmett was born in Ohio), but rather the warmer climate where the production companies would travel to escape the harsh northern winters. Before long the song became a huge success and was adopted by the Confederacy. Ironically, Emmett was later scorned for writing “Dixie” and falsely labeled a secessionist.

There are many other fascinating tidbits in the Kellys’ new book. The last chapter has profiles of four of the most prominent generals’ wives: Grant, Lee, Sherman, and Jackson. For those readers looking for something a little different about our country’s bloodiest war, Best Little Stories of the Blue and Gray is a perfect choice.

Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring by Alexander Rose, Bantam, New York, 2006, 370 pp., illustrations, index, $26.00, hardcover.

Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring by Alexander Rose, Bantam, New York, 2006, 370 pp., illustrations, index, $26.00, hardcover.

Intelligence-gathering is a necessary component to any army. Knowing the enemy’s movements, his strength, and weapons are integral if victory is to be achieved.

During the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army was in its infancy, as was its intelligence arm. General George Washington’s unlikely group of agents numbered only a handful, but their derring-do and cunning outmatched the British and provided Washington with invaluable information on Her Majesty’s forces.

Included in the ragtag spy ring was a Quaker who wrestled with his morals, a whaler who relished the mystery and danger of being a spy, a bartender who drank more than his patrons, a Yale graduate who volunteered for the cavalry, and a farmer who complained to Washington repeatedly of various ailments and begged to return to his home. These individuals from diverse backgrounds would be dubbed the Culper Ring, and Washington would use them and their secret codes to watch the movements of the British.

At war’s end, the members of the Culper Ring faded away to live their lives in relative anonymity. Their exploits were never fully realized by a grateful nation. This book gives long overdue recognition to the shadowy people who risked their lives to win America’s freedom.

No True Glory: A Frontline Account of the Battle of Fallujah by Bing West, Bantam Books, New York, 2006, 376 pp., illustrations, index, $14.00, softcover.

No True Glory: A Frontline Account of the Battle of Fallujah by Bing West, Bantam Books, New York, 2006, 376 pp., illustrations, index, $14.00, softcover.

Retired Marine Bing West traveled to Iraq and was imbedded with the leathernecks in the initial invasion of that country in 2003. He co-authored a brilliant account of the action in The March Up. He has followed up that success with his new book centering on the seizure of Fallujah, a known insurgent haven west of Baghdad.

Fallujah will rank as one of the toughest assignments ever handed to the U.S. Army and Marine Corps. With its maze of buildings and narrow streets, the city saw fighting that was reminiscent of Hue City during the 1968 Tet Offensive in the Vietnam War.

West interviewed hundreds of individuals involved in the campaign—everyone from the top commanders down to the “grunts” actually immersed in the deadly urban combat. The book concentrates on the week of November 7 through November 13, 2004, when the Marines confronted the insurgents in bloody house-to-house and hand-to-hand combat.

No True Glory is a powerful, no-nonsense look at the gritty, unflinching world of the infantryman in time of war. In the end, however, the American soldiers persevered at Fallujah and could claim an overwhelming, if short-lived, victory against the various factions then in control of the city.

Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy by Ian W. Toll, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2006, 540 pp., illustrations, index, $27.95, hardcover.

Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy by Ian W. Toll, W.W. Norton & Co., New York, 2006, 540 pp., illustrations, index, $27.95, hardcover.

When the United States won her independence from Great Britain, first and foremost on the minds of the Founding Fathers was the formation of a sound military to fend off other enemies from abroad. The building of ships to form a sizable sea-going navy was paramount to that thinking.

From the outset, the newly formed U.S. Navy received scant respect from the world powers of their day, Great Britain and France. These upstart Americans were new to the high seas and were not considered a force to be reckoned with. Then the War of 1812 was waged once again against Mother England.

When the Treaty of Ghent was signed in 1815, ending hostilities between the two countries, America’s former masters had a grudging, newfound respect for the Americans, especially their navy. As Winston Churchill (himself half-American) wrote in his monumental History of the English-Speaking Peoples, “Anti-American sentiment in Great Britain ran high for several years, but the United States was never again refused proper treatment as an independent Power. The British Army and Navy had learned to respect their former colonials.”

11 Days in December: Christmas at the Bulge, 1944 by Stanley Weintraub, Free Press, New York, 2006, 256 pp. illustrations, index, hardcover.

11 Days in December: Christmas at the Bulge, 1944 by Stanley Weintraub, Free Press, New York, 2006, 256 pp. illustrations, index, hardcover.

In December 1944, Adolf Hitler gambled on his most audacious plan yet: a surprise attack on the Allies just before Christmas in 1944. What would become known as the Battle of the Bulge was the Nazi leader’s last-ditch effort to defeat the British, Canadian, and American units then poised to strike at Germany itself.

Through various accounts from the top commanders down to the privates in the foxholes, Weintraub explains how the Americans fought off the German onslaught in spite of scant supplies and bone-chilling temperatures. The weather was dismal, and snow and low overcast skies prevented aircraft from flying missions to support the ground troops. Without air cover, the battle became an infantryman’s war until the stormy conditions passed and the sun finally appeared.

Losses on both sides were harrowing: Americans suffered nearly 81,000 killed, wounded and missing. The German losses were even worse, with over 98,000 casualties. In addition, thousands of French and Belgian civilians were killed as well. The abortive German breakthrough at the Ardennes was costly for all involved. But in the final analysis, the Battle of the Bulge would prove to be the last turning point of World War II.

The Pirate Coast: Thomas Jefferson, the First Marines, and the Secret Mission of 1805 by Richard Zacks, Hyperion, New York, 2005, 432 pp., illustrations, index, $25.95, hardcover.

If you like intrigue, action, and suspense, then The Pirate Coast is the book for you. In 1805, nearly 300 American sailors and Marines were taken prisoner when the USS Philadelphia ran aground in Tripoli harbor. President Thomas Jefferson sent an unlikely individual, disgraced Army officer and diplomat William Eaton, on a covert mission to rescue the beleaguered Americans from the hands of the Tripoli pirates.

What transpired was an amazing story of endurance and courage in the face of overwhelming odds, as Eaton and his small party traveled across the harsh African terrain to free his fellow countrymen. Despite Jefferson’s last-minute withdrawal of money and troops, the Americans reached their objective and successfully completed their task.

Eaton returned to the United States and publicly denounced Jefferson for his lack of support. The wily Jefferson soon went on the defensive and turned the tables on Eaton, who was himself publicly humiliated. Nonetheless, it was Eaton who deserved the credit for giving the country a newfound respect on the world scene.

The Few: The American “Knights of the Air” Who Risked Everything to Fight in the Battle of Britain by Alex Kershaw, Perseus Books Group, Cambridge, MA, 2006, 344 pp., photographs, index, $25.00, hardcover.

The Few: The American “Knights of the Air” Who Risked Everything to Fight in the Battle of Britain by Alex Kershaw, Perseus Books Group, Cambridge, MA, 2006, 344 pp., photographs, index, $25.00, hardcover.

In 1940, Great Britain was fighting for her very survival against a determined Nazi Germany that was bent on subjugating the English in its ruthless quest for world domination. The British fought on valiantly and fully expected an invasion from Adolf Hitler’s army at any moment.

A small band of pilots formed the nucleus of the Royal Air Force, which met the Luftwaffe in the skies over England. Outmanned and outnumbered, the RAF pilots managed to successfully outfight the Nazis. Eager to get involved, some Americans left the safety of the United States and volunteered to fly with the RAF.

Rebelling against America’s neutral stance at this early point of the conflict, the inexperienced pilots, with minimal training, dared to meet top German aces and assist England in defeating tyranny. They became known as the “Knights of the Air” and were renowned in Great Britain. By the fall of 1940, the RAF had turned the tide and beaten back Hitler’s fanatical air force. Sadly, only one American Knight of the Air would be alive when peace finally came in 1945. This book is a lasting tribute to his—and their—memory.

The Search for Corporal Dow by Eugene C. & Linda M. Solyntjes, Precision Shooting, Inc., 2006, 212 pp., hardcover.

The authors have written an excellent reference book surrounding a Sharp’s rifle and the mysterious Union soldier who owned it. The story is an exciting sojourn that resulted in discovering the identity of Union Corporal William H. Dow, who first enlisted in Company I, 2nd Wisconsin Regiment, in 1861 and served for three years. Taken prisoner by the Confederates, Dow was released and later fought at Second Bull Run, Antietam, Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, and Gettysburg. He mustered out but returned to the army and was assigned to Company K, 2nd Regiment, I Corps, where he was issued his Sharp’s rifle. The old veteran survived the conflict and died in the Old Soldier’s Home in 1927.

Included in the book are a multitude of websites, addresses, and various organizations to assist the reader who wishes to investigate a relative who may have served during that same period. Also, a history of various rifles and pistols photographed in color are in the book as well.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments