By Flint Whitlock

Within his reinforced concrete bunker, 50 feet below the garden of the New Reichs Chancellery on Berlin’s Wilhelmstrasse, German dictator Adolf Hitler, his soon-to-be bride Eva Braun, and several hundred friends, SS guards, and staff members could feel the concussion and hear the unending drumroll of thousands of Soviet artillery shells reducing the already-battered capital city of the Third Reich to unrecognizable rubble.

Outside in the city’s shattered streets, ragtag elements of Wehrmacht and SS units, augmented by ill-trained Volkssturm troops—mostly old men and young boys—were doing their best to hold off determined brigades of Soviet infantry, but it was an unequal fight. With 180 Soviet divisions, 9,000 Russian tanks, and 9,000 warplanes pushing through Poland against only 80 German divisions, and the Yanks and Tommies having penetrated Germany from the west, V-E Day and the Third Reich’s demise was clearly in sight.

Hitler Ever Delusional

Hitler, living in his netherworld of unreality, swung between moods of rage, self-pity, confidence, and despair. He could only count on his closest associates; everyone else had let him down. During the Third Reich’s final days, Hitler especially held no love for the German people, for whom he had gone to war and who now, he was convinced, were unworthy of his efforts.

In March, as the enemy closed in on Berlin from all sides and pounded it from the air, Hitler told his favorite architect Albert Speer, “If the war is lost, the nation will also perish. This fate is inevitable. There is no necessity to take into consideration the basics which the people will need to continue a most primitive existence. On the contrary, it will be better to destroy those things ourselves because this nation will have proved to be the weaker one and the future will belong solely to the strong eastern nation [Russia]. Besides, those who will remain after the battle are only the inferior ones, for the good ones have been killed.”

Issuing the “Scorched Earth” Order

The following day, Hitler issued a “scorched earth” order: everything of value within Germany was to be destroyed to keep it from the hands of the conquerors—an order Speer did his best to contravene. Hitler was determined that he, too, would be utterly destroyed so that he would not wind up as a war trophy, stuffed and mounted and hanging in some Moscow museum.

Hitler and the other surviving Nazi officials had good reason to fear their fate. Ever since Operation Barbarossa, Germany’s massive invasion of the Soviet Union in June 1941, the Germans had laid waste to vast regions of the communist nation. Einsatzgruppen, or Special Action Units, following in the wake of the shock troops, rounded up innocent civilians and ruthlessly slaughtered them, putting whole villages to the torch. Millions of Russians—some say as many as 20 million—perished during what the Soviets called the “Great Patriotic War.”

“General Winter” Stops the German Advance

Shoved back nearly to the gates of Moscow in December 1941, Josef Stalin’s desperate troops and “General Winter”—the worst weather in a century—stopped the relentless German advance. While they waited and waited for the United States and Britain to invade the European continent and open a second front, the Soviets held on heroically. Slowly, the Russians began to turn back the tide of the war, inflicting enormous casualties on the Germans in the process.

In January 1943, while Field Marshal Friedrich von Paulus was surrendering 91,000 frozen, starving men at Stalingrad—all that was left of his once mighty, 200,000-man Sixth Army—President Franklin D. Roosevelt and British Prime Minister Winston S. Churchill were meeting in Casablanca, where they discussed the idea of demanding the unconditional surrender of Germany. Stalin, who was not present, voiced his support of the idea. Only through eschewing negotiation and requiring capitulation without condition could the Allies hope to drive a permanent stake once and for all through the black heart of Nazi Germany.

Jet Fighters, U-Boats and Ballistic Missiles

Now, in 1945, more than two years after Casablanca, Germany’s railroads had been smashed, most of the still-serviceable warships of the Kriegsmarine and the warplanes of the Luftwaffe lay idle for lack of fuel, and rations for both the military and civilian population stood barely at subsistence levels. Units that tried to hold back the Allies were overwhelmed and annihilated.

But, like a cornered and wounded beast, Nazi Germany was still a dangerous adversary. One of Hitler’s “wonder weapons,” the revolutionary Me-262 jet fighter, was tearing through Allied bomber formations and wreaking havoc; fortunately for the Allies, there were too few jets and their overall effect was minimal. The V-1 flying bombs and V-2 ballistic missiles, however, remained a constant, if inaccurate, menace. A whole new class of submarines, known as electro U-boats, were designed to pose a danger to Allied shipping, but only two of the 126 planned or partially constructed boats had been commissioned. There were plans for new and devastating rifles and flamethrowers. Some in the Allied camp fretted about persistent rumors of a Nazi atomic bomb.

A Hard Fall for the German Dictator

From the west, the Americans and British approached with 85 divisions; the Soviets in the east had more than double that number. In April 1945, the German high command issued a decree that any commander failing to stand and fight to the last man would be executed. As his world crumbled around him, Hitler fired any general he thought was disloyal or defeatist and took the defense of the Reich directly into his own hands.

How had it come to this? Things had started so promisingly for the Nazi regime in January 1933. After scheming, bluffing, and bullying his way into the respected office of chancellor, Hitler initially made good on his campaign promises. Millions of unemployed workers found jobs, created for the most part by a giant government works program similar to Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps. Runaway inflation was brought under control, and the economy staged a miraculous comeback.

The gangs of Communists that had been agitating for the overthrow of the Weimar government and causing chaos in the streets were brutally crushed. Hitler’s promises to restore Germany’s military might and regain the territory lost via the Treaty of Versailles accords had also come true. Men such as king Edward VIII, of England the aviation hero Charles Lindbergh, and United States Olympic Committee Chairman Avery Brundage were, in the 1930s, in awe of the law-abiding order the Nazis had brought to Germany.

But Hitler had his heart set on other goals, mainly revenge—both against Germany’s neighbors and against the Jews, on whom he blamed Germany’s defeat in the Great War; the lives of the Jews would grow steadily worse.

The bloodless takeovers of the Rhineland and the Sudetenland, and the annexation of his native Austria, emboldened Hitler to greater and greater acts of belligerence. Soon, after all-out war was declared upon Poland, France, Great Britain, Russia, and others, Germany had embarked on a one-way journey to either glory or disaster.

As the war began to go badly for the Nazis, Germany’s allies began falling away. The first was Italy, which had officially dropped out of the Axis partnership in September 1943, on the eve of invasion. King Victor Emmanuel III had unceremoniously dumped the Italian dictator, Benito Mussolini, and had him arrested. Although the king and Mussolini’s replacement, Marshal Pietro Badoglio, initially said Italy would be neutral, the leaders declared war on Germany on October 13, 1943. Nevertheless, some loyal Fascist Italian units continued to fight on at the side of the Germans. The war in Italy would go on.

Next to leave the Nazis’ camp was Romania, which switched sides and, on August 25, 1944, declared war on its former partner, followed by Bulgaria (September 9) and Hungary (January 21, 1945).

Eisenhower’s Decision to Avoid Berlin

As early as September 1944, General Dwight D. Eisenhower, head of the Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF), had broadly outlined how he wanted the final battle for Germany to be fought. Eisenhower originally planned to have Field Marshal Sir Bernard Law Montgomery’s 21st Army Group, with the U.S. Ninth Army attached, crash through the Ruhr and head for Berlin. But in late March Eisenhower had second thoughts. Getting through the heavily industrialized area would be no easy feat, especially for a cautious general like Montgomery, who was known more for his meticulous planning and preparation than for an aggressive, hell-bent-for-leather approach.

Eisenhower also looked at his situation maps. He saw that the vanguard of the Soviet forces was only 30 miles from Berlin while the closest American or British units were 275 miles away. He decided it would be better to have Montgomery’s divisions encircle two enemy army groups in the Ruhr and allow Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group to head due east, toward Leipzig and Dresden.

Eisenhower also knew that anyone getting involved in the battle for Berlin would be in for a terrible blood-letting. Besides, the general plan for the post-war administration of Germany had already been agreed to. Disregarding the political implications of allowing the Russians instead of the Western Allies to take Berlin, Eisenhower pulled the Ninth Army away from Montgomery and gave it back to Bradley for the eastward push.

The British, as might be expected, were doubly unhappy with Eisenhower’s decision, first because Montgomery and the British Army were reduced to a supporting role, and second because Eisenhower was ceding the main prize—Berlin—to the Soviets. Churchill even appealed to both Eisenhower and President Roosevelt, saying, “Berlin remains of high strategic importance. Nothing will exert a psychological effect of despair upon all German forces of resistance equal to that of the fall of Berlin. It will be the supreme signal of defeat to the German people.” But Roosevelt was not opposed to allowing the Russians the “honor and glory” of capturing Berlin; perhaps the show of such international cooperation and goodwill would persuade the Soviets to assist the U.S. in the final stages of the war against Japan in the Pacific.

In the West, the Yanks were making good progress. On April 12, an American unit captured one of the Nazis’ “heavy water” facilities at Stadtilm near Erfurt that was thought to be crucial to the manufacture of an atomic weapon. And even though no hope existed for Germany to win the war, the death factories at Bergen-Belsen, Auschwitz, and elsewhere worked overtime to kill and cremate as many Jews as possible. Five days later, the American 45th Infantry Division reached Nuremburg, drenched the city with artillery fire, then blew up the large stone swastika that dominated the huge stadium where once Hitler and hundreds of thousands of his fanatical followers had performed their ceremonies.

“This was the Angel of History!”

Despite the oppressive atmosphere of doom and gloom that pervaded the Führerbunker, Hitler rejoiced after midnight on Friday, April 13, when Josef Goebbels, his minister of propaganda, phoned him with the news that Roosevelt had just died. Convinced that Roosevelt’s death was an act of providence, Hitler was delighted. Goebbels’ state secretary noted in his diary, “This was the Angel of History! We felt its wings flutter through the room. Was that not the turn of fortune we awaited so anxiously?” On April 15, Hitler declared, “At the moment when fate has removed the greatest war criminal of all time from the earth, the turning point of this war shall be decided.”

Hitler then turned toward more domestic matters—his wedding. Eva Braun had just arrived in Berlin to join him. William L. Shirer wrote, “Very few Germans knew of her existence and even fewer of her relationship to Adolf Hitler. For more than twelve years she had been his mistress. Now in April she had come … for her wedding and her ceremonial death.”

At 5 am the next day, the Red Army, ringing Berlin, began its final offensive against the capital with a barrage of 500,000 artillery shells, tank rounds, mortars, and rockets. Three thousand Russian tanks then were sent to penetrate the city. Sixty German suicide pilots attempted to crash their planes into the bridges over the Oder River in an effort to deny them to the Russians, but most of the tanks, and the infantry behind them, crossed the river. Helping the Soviets were American pilots, who shot down 22 of the German jet fighters over Berlin. The urban fighting became house to house, room to room, hand to hand. Eisenhower’s prediction that Berlin would become a bloodbath had come true.

By now the German military machine everywhere was in disarray—crumbling, retreating, fighting for its life, dying by the thousands, surrendering in droves.

Meanwhile, south of Berlin, American and Soviet units were drawing closer to one another, as if pulled by a magnetic field. On April 19, the American 2nd and 69th infantry divisions entered Leipzig, 90 miles south of the capital. At the same time, the Russians broke through German defenses at Forst, 75 miles southeast of Berlin.

Hitler’s Birthday in the Bunker

The next day was Hitler’s birthday, which was celebrated in the bunker in subdued fashion. His faithful minions—Josef Goebbels, Reichsmarshal and Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring, Reichsführer-SS Heinrich Himmler, Foreign Minister Joachim von Ribbentrop, personal secretary Martin Bormann, Kriegsmarine commander Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, General Alfred Jodl, Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel, and General Hans Krebs, the latter the newly appointed chief of the general staff—were all in attendance.

Although Hitler confidently maintained that the Soviets would suffer a major defeat in Berlin, his sycophants knew better; they tried to convince him to leave the city and head south before all escape routes were severed. Hitler declined the invitation but did set up two separate commands—one in the north headed by Dönitz, and another in the south, to be commanded by either Göring or Field Marshal Albert Kesselring. Should Berlin fall and communications with his field commanders be cut off, Hitler wanted these two commands to be able to carry on the war independently.

The Flight of Himmler and Göring

Those closest to the Führer turned out to be the most disloyal, and the leading Nazi rats began abandoning the sinking ship of state. After the birthday celebration, Göring and Himmler, who both clearly recognized the handwriting on the wall, said their goodbyes and then made their hasty retreats out of burning Berlin. Göring headed for Carinhall, his palatial, 100,000-acre country estate in the Schorfheide forest 40 miles north of Berlin, to ponder his next move. He felt the only sensible course of action, given the imminent likelihood of Berlin’s fall and Hitler’s death, would be for him to assume the leadership of the Third Reich. That way, Göring believed, he could spare Germany further destruction—and perhaps even escape death at the hands of the Allies.

Göring decided to head south to his villa at the Obersalzburg, near Berchtesgaden, where the Nazi leadership all had homes in a special compound at the foot of the Alps. A fleet of trucks stood by, filled with his furniture and other household items; his fabulous collection of stolen artwork that once graced the walls of Carinhall had already been removed and was safely in tunnels beneath the mountains of Berchtesgaden or in sealed salt mines in Salzburg. After shaking hands with the remaining staff, Göring and his wife, Emmy, climbed into his huge Mercedes and left. Shortly after his departure, German demolition experts, following his orders, placed the charges that would destroy his beloved estate.

Himmler had similar ideas. Hitler’s closest friend, most trusted associate, head of the dreaded SS, and mastermind of the Holocaust, Himmler headed north to Lübeck on the Baltic coast for a clandestine meeting with Sweden’s Count Folke Bernadotte, president of the International Red Cross, on April 23. Also assuming that Hitler would soon be dead, Himmler urged the Count to contact General Eisenhower’s headquarters and arrange for a surrender. The former chicken farmer—who told Bernadotte that he, Himmler, likely would be named Führer once Hitler was gone—hoped that the American and British armies would rush to the east and join what few German units still remained to hold off the barbaric Russian hordes. He would be declared a hero and thus spared the hangman’s noose or a firing squad.

Himmler’s pleas for a negotiated peace were summarily rejected, and the frightened Reichsführer SS, suffering from psychosis and terrified at the prospect of what the Soviets would do to him if they captured him, left the meeting and changed identities in order to save his own hide. He shaved off his distinctive mustache, donned a common Wehrmacht uniform, put a patch over one eye, changed his name to Heinrich Hitzinger, and hoped to slip out of Lübeck and meld into the crowds of thousands of soldiers who had surrendered to the British. His escape attempt failed; he was soon captured and his true identity revealed.

Amazingly, Hermann Göring managed to elude the enemy and reach the Obersalzburg. He knew that in 1941 Hitler had named him as his successor but was unsure if that decision was still in force or if Bormann had risen in Hitler’s estimation and taken his place. A nervous Göring sent a message to Hitler on April 23, essentially saying that unless he received contrary word by 10 pm that evening, he would proclaim himself Führer. Outraged at Göring’s presumptiveness and act of “high treason,” Hitler demanded that Göring resign all of his titles and offices, then ordered his arrest and execution. Bormann sent out the arrest order to the SS commandant at the Obersalzburg.

On April 24, two SS officers with 100 men barged into Göring’s house and declared that he and his family were under arrest. At 9 am the next day, two waves of British bombers flew over the compound and unleashed their deadly cargo; Hitler’s house, the Berghof, was destroyed, along with Bormann’s. A bomb landed in the swimming pool outside Landhaus Göring and demolished the building. For his own safety—and theirs—the SS guards whisked Göring off to a castle at Mauterndorf, Austria. One of Göring’s aides sent a detachment of Luftwaffe men to Mauterndorf to help protect the air force head, and it was not long before the SS men began to waiver. Göring pleaded with his captors to be allowed to travel for a personal meeting with Eisenhower; such a visit would undoubtedly save the Reich from Russian ruin. The SS finally let him, his wife, and his staff go. He and his entourage hoped to find some Americans to whom he could surrender and carry out his historic mission.

East Meets West

In the east, three million Soviet soldiers were advancing on a broad front. The Russians informed Eisenhower that they intended to capture Berlin and the east bank of the Elbe River north and south of the city, as well as take over all of Czechoslovakia. Eisenhower approved, and the Americans and Soviets agreed to link up somewhere south of Berlin, between the Mulde and Elbe Rivers.

On the morning of April 25, four patrols from the American 69th Infantry Division near the towns of Wurzen and Trebsen on the Mulde, set out to the east. The first to make contact was a 35-man patrol led by 1st Lt. Albert L. Kotzebue of Company G, 273rd Infantry Regiment, 69th Division. At 11:30 am, Kotzebue and his men encountered a lone, horse-mounted Russian cavalryman in the small farming village of Leckwitz. Soon Kotzebue found himself meeting with the commander of the 175th Rifle Regiment. But because Kotzebue had mistakenly reported the wrong map coordinates regarding his link-up with the Russians, higher command was unsure of the veracity of the report.

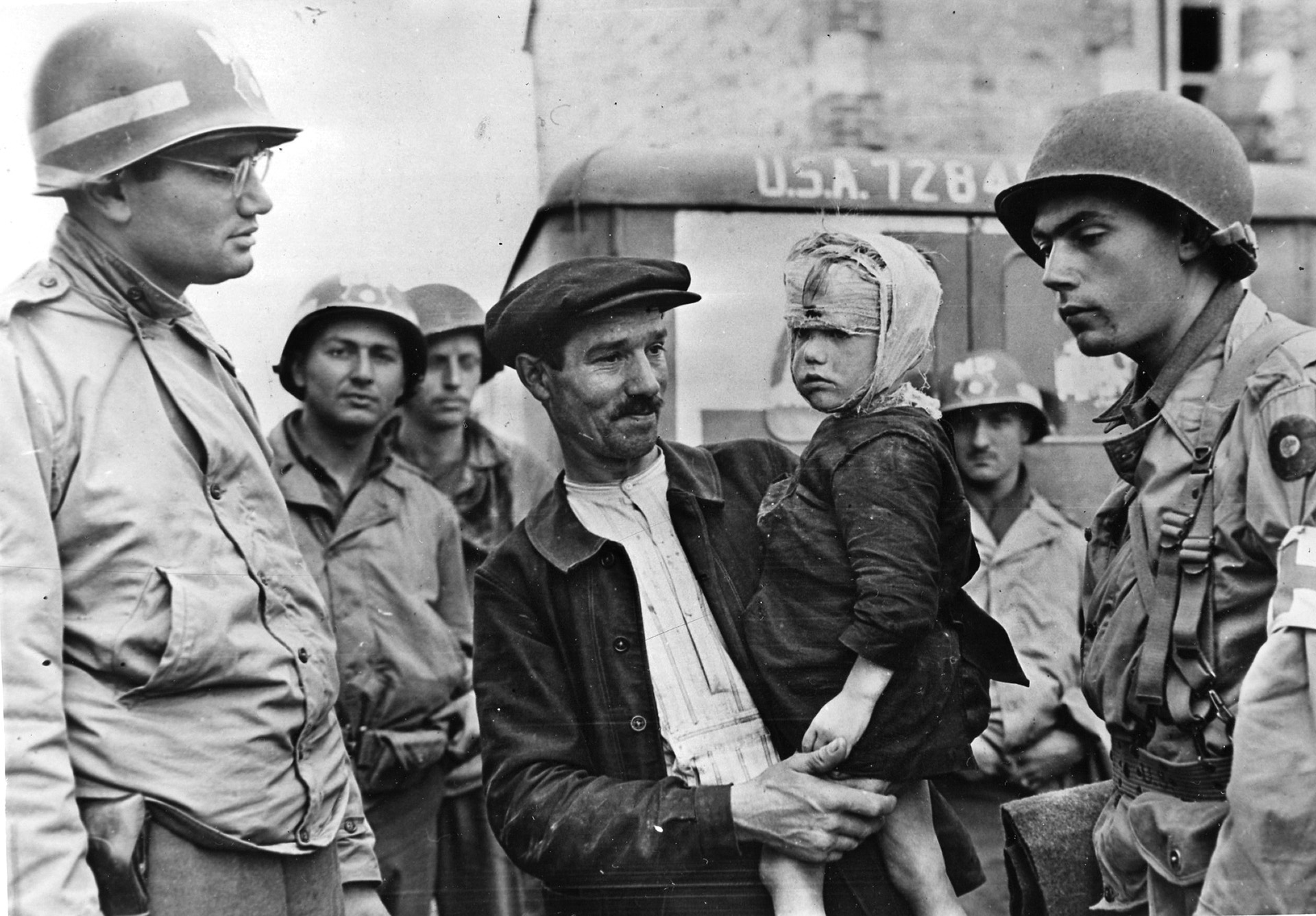

Three other patrols also contacted Soviet troops later that day, but it was the meeting between 2nd Lt. William D. Roberston’s patrol and the Russians at about 4 pm in Torgau that became recognized as the official meeting. Entering the town, Roberston’s men took a number of Germans prisoner and freed a group of POWs of various nationalities. To let the advancing Russians know that the town was in U.S. hands, Roberston wanted to raise an American flag from the tower of a castle there, but no one had thought to bring a flag along. Using a white sheet and some paint they found in a shop, Roberston’s men fashioned a crude flag that was then hoisted above the fortress. Crawling over the twisted girders of a destroyed bridge across the Elbe, grinning American and Russian soldiers shook hands and slapped each other on the back.

Roberston took several 173rd Rifle Regiment officers back to his battalion headquarters in Wurzen, and the word flashed out that the two sides had met. Although it was Kotzebue’s patrol that had first made contact with the Soviets in Leckwitz, it was Torgau that went down in history as the place where the two sides finally joined. The formal celebrations between division commanders—the American 69th and the Russian 58th Guards divisions—were held on April 26.

Germany’s Long Surrender

The surrender of Germany did not take place all at once or even in the same place. Indeed, there were at least 11 separate surrender ceremonies. The first came on the afternoon of Sunday, April 29, 1945, in Caserta, Italy. Here, in the Bourbon Royal Palace, 10 miles north of Naples, Lt. Col. Viktor von Schweinitz, dressed incongruously in a plaid sportcoat, shirt, tie, and slacks, signed the documents on behalf of Col. Gen. Heinrich-Gottfried von Vietinghoff genannt Scheel, commander-in-chief of Army Group C.

In Berlin, Hitler finally accepted the fact that Germany was doomed. In the early hours of April 29, he married his longtime mistress Eva Braun in the surrealistic atmosphere of the besieged bunker; Goebbels and Bormann signed the marriage contract as witnesses.

While the bombs and shells thudded above the Führerbunker, Adolf Hitler, his nerves shot and his eardrums shattered by the attempt on his life 10 months earlier, dictated his last will and testament to his favorite secretary, Traudl Junge. It was more of a bitter tirade than a testament. According to William Shirer, the testament confirmed that “the man who had ruled over Germany with an iron hand for more than twelve years and over Europe for more than four, had learned nothing from his experience; not even his reverses and shattering final failure had taught him anything. Indeed, in the last hours of his life he reverted to the young man he had been in the gutter days of Vienna and in the early rowdy beer hall period in Munich, cursing the Jews for all the ills of the world, spinning his half-baked theories about the universe, and whining that fate once more had cheated Germany of victory and conquest.… It was a fitting epitaph of a power-drunk tyrant whom absolute power had corrupted absolutely and destroyed.”

Hitler rambled on, railing against the German officer corps on whom he blamed Germany’s defeat, condemning the “treachery” of Göring and Himmler for abandoning the Nazi cause, and finally naming Dönitz, head of the navy, as his successor. Exhausted from a night of constant dictation, Hitler then retired to bed. Three messengers were selected to take copies of the testament through the Russian encirclement to Dönitz. Although the couriers were able to sneak through the Soviet lines, they never reached the admiral; he learned about his appointment via a radio message from Martin Bormann.

At noon on the 29th, an unusually calm Hitler awoke and conducted his daily military briefing with his dwindling staff. The situation was dire; the Russians were inching closer to the bunker and the number of defenders and their ammunition were both running perilously low. A hoped-for army of rescuers had not been heard from, and a sobering message detailing the death of Mussolini reached Hitler.

On April 25, Benito Mussolini, who had been daringly rescued from his mountaintop hotel prison months earlier at Gran Sasso d’Italia by Otto Skorzeny’s commandos, had returned to his villa at Lake Garda, hoping to rally his diehard followers to him for a final stand. The Germans were not sure of his intentions so, with an SS escort there to prevent him from suddenly changing his mind and seeking asylum in Switzerland, Il Duce motored in convoy to the Lake Como town of Dongo. There, Mussolini was recaptured by Italian Communist partisans and, on April 28, gunned down. His corpse, along with that of his mistress Claretta Petacci, was abused by his countrymen and strung up by the heels at a Milan gas station.

The evening briefing confirmed that the situation remained unchanged, except for further deterioration. After dictating more tirades against the army, its generals, and the traitors Göring and Himmler, Hitler had his favorite dog, Blondi, poisoned, then retired to his sparsely furnished concrete quarters with his new wife. At about 2:30 am on April 30, he reemerged, shook hands with the remaining members of his staff, and then, with eyes welling up with tears, once more returned to his quarters.

After so many days of tension, the reality of the end hit the staffers in an odd way. A party broke out, filled with laughter, drinking, and dancing; many realized that it was just a matter of time before the Russians crashed the party and captured or killed them all, so why not have a little fun? So loud did the frivolity become that a request for quiet came from the Führer’s quarters.

Hitler’s Last Meal

At noon on the 30th, another situation briefing was held—the battle of Berlin was intensifying and the Soviets were within a block of the bunker. After a lunch at which Hitler ate his last meal, he returned for the final time to his quarters. With Goebbels and Bormann hovering in the hallway outside the room, at 3:30 pm a single shot rang out from behind the door. The two men entered and found Hitler sprawled on the sofa, his face blown apart by a bullet shot through the mouth; beside him lay Eva Braun Hitler, who had taken cyanide. The bodies were wrapped in blankets, carried up the bunker’s emergency stairs, placed in a shell hole in the garden, doused with gasoline, and set afire. The news that the Führer had died a hero’s glorious death was broadcast over state radio to the German people on May 1.

After Hitler’s death, Bormann slipped out of the bunker and disappeared into the burning, blasted ruins of Berlin, never to be seen alive again. Goebbels and his wife, Magda, loyal to the end, chose a different course. Not wishing to live in a world without their beloved Führer, on the night of May 1 the couple poisoned their six children who were living in the Führerbunker with them. They then went up to the garden where, at their request, an SS soldier killed each with a shot to the back of the head; aides poured gasoline on the two corpses and torched them. The Russians, when they finally reached the bunker the next day, found only the charred remains.

After the deaths of the Goebbels family, most of the staff and SS guards began to scatter, hoping to escape to the west, beyond the clutches of the Russians. They had no desire to die for a dead leader and a defeated Germany.

Karl Dönitz Leads the Surrender of Germany’s Armed Forces

On May 2, Grand Admiral and Führer Karl Dönitz made the decision that to continue fighting would serve no good purpose and so sent an emissary to Montgomery to arrange for a surrender. At 11:30 am the following day, Admiral Hans Georg von Friedeburg, new head of the Kriegsmarine, and General Hans Kinzel, acting as emissaries of Field Marshal Ernst Busch, appeared at Montgomery’s headquarters in Wendisch Evern on the Lüneburg Heath to surrender three armies that were facing the advancing Soviets to the east. Montgomery refused the offer, saying that since they were fighting the Russians they must surrender to the Russians. The German delegation, in turn, declined to surrender the armies that were trying to hold back Montgomery’s divisions in the west.

Montgomery decided to show the German officers exactly what they were facing. “I wonder whether you officers know what is the battle situation on the Western Front,” he told them. “In case you don’t, I will show it to you.” He then revealed a map that had plotted on it the positions of all the units under his command. “That situation was a great shock to them. They were quite amazed and very upset. I was perfectly frank and held back no secrets. They were in a condition—and in a very good, ripe condition—to receive a further blow.”

Montgomery again demanded that the Germans unconditionally surrender all German forces in Holland, Denmark, Schleswig-Holstein, Friesland, Heligoland, and various islands. After a lunch break that allowed them to reconsider, the Germans replied that they had not the authority to agree to such a comprehensive plan but would return to their headquarters in hopes of securing an agreement.

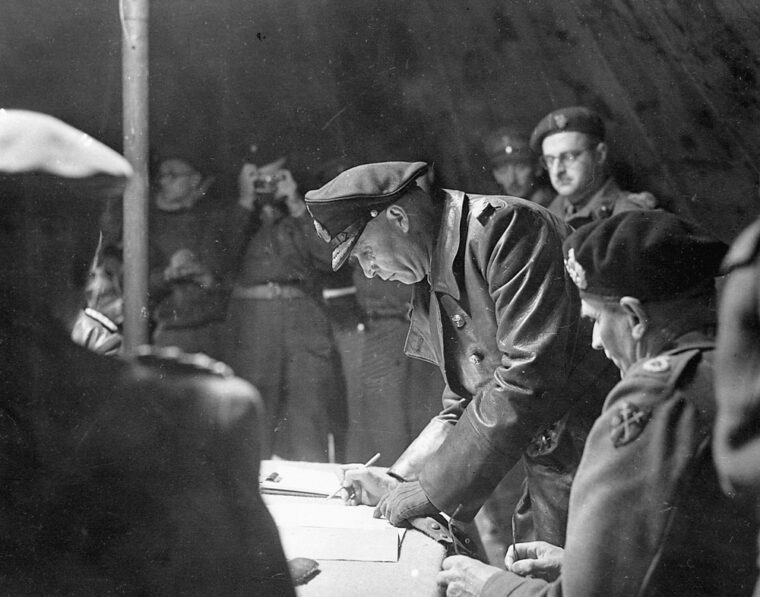

The next day, May 4, the German officers, with permission from Dönitz to agree to Montgomery ’s terms, returned. In a brief ceremony, the one-sheet surrender document was signed by all parties.

Following Dönitz’s lead, German commanders began laying down their arms. Near Innsbruck, Austria, on May 4, a delegation from General Erich Brandenberger, commander of the Nineteenth Army, approached the forward elements of Maj. Gen. William F. Dean’s 44th Infantry Division with a request to discuss terms of surrender. The next day, after meeting with Major General Edward H. Brooks, commanding general of VI Corps, Brandenberger unconditionally surrendered his army; a cease-fire went into effect at 6 pm that same day.

Twelve miles east of Munich, in the town of Baldham where XV Corps had its headquarters, General Friedrich Schultz, head of Army Group G which controlled all units between Switzerland and the Austro-Czech border, formally dropped out of the war. Also attending the ceremony for the Americans, besides XV Corps commander Maj. Gen. Wade H. Haislip, were Lt. Gen. Jacob Devers, commander of the 6th Army Group, and his boss, Lt. Gen. Alexander Patch, Seventh Army commander. This surrender caused no little consternation among the French, who were angered at having been left out of the negotiations.

In Holland, the German commanders had the same idea as their comrades in Italy, Bavaria, and Schleswig-Holstein. On May 5, Col. Gen. Johannes Blaskowitz, head of the Twenty-fifth Army, arrived in the badly damaged town of Wageningen, 10 miles east of Arnhem, to surrender all the German units in the Netherlands to Lt. Gen. Charles Foulks, commander of the I Canadian Corps and Prince Bernard, commander-in-chief of the Netherlands Forces of the Interior. The formal signing took place the next day and, that evening, Dutch Queen Wilhelmina went on the air to broadcast the news of the German surrender to her joyful subjects.

Germany’s Official Surrender

Germany’s formal surrender to the Soviets took place in the Berlin suburb of Karlhorst on May 8. The document was signed for the Germans by Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel. Signing for the Soviets was Marshal Georgi Zhukov; for SHAEF by Eisenhower’s Deputy Supreme Commander Air Chief Marshal Sir Arthur Tedder; for the U.S. by General Carl Spaatz; and for France by General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny.

Other surrender ceremonies took place in early May at Lorient, St. Nazaire, and Dunkirk, France, as well as the Channel Islands.

At SHAEF headquarters in Reims, France, what many considered the “official” surrender to Eisenhower was conducted. The German delegation, headed by Jodl and accompanied by Friedeburg (who would commit suicide on May 23), stalled for time in hopes that units fighting the Soviets would have time to disengage and escape to the west. Eisenhower would have none of it. At 2:41 am, on May 7, Jodl signed the Act of Military Surrender.”SHAEF headquarters cabled a brief statement to the Combined Chiefs of Staff: “The mission of this Allied force was fulfilled at 0241 local time, May 7, 1945.”

On May 7, the 36th Infantry Division (Texas National Guard), with its command post in Kufstein, Austria, was feeling pretty good about itself. The Texans had bagged one of the Germans’ top men—Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt—and were about to add another. Learning that Göring wanted to surrender, the 36th’s assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Robert I. Stack, took a patrol into Bavaria and met Göring’s 25-vehicle convoy headed his way. Göring and his entourage willingly gave themselves up. Stack interrogated the Reichsmarshal, especially about the presumed “National Redoubt,” a rumored last stand defensive fortification in the Alps where it was believed that hardcore Nazis could hold out for years. Göring admitted the Redoubt did not exist.

Göring was then flown to Lt. Gen. Patch’s Seventh Army headquarters in Augsburg, where he was imprisoned and waited to stand trial as a war criminal. The war-crimes trial of the top surviving Nazis was held in Nuremburg throughout most of 1946. Vain, bombastic, and egocentric, Göring—who had founded the Gestapo and had given Reinhard Heydrich the order to exterminate the Jews—was by far the most colorful and dominating personality of the trial. But he failed to sway the tribunal judges and, along with 11 of the other defendants, was sentenced to death. Göring would cheat the executioner; on October 15, 1946, two hours before he was to be hanged, he was found dead in his cell. He had taken cyanide.

Himmler did not wait to be tried. On May 23, while still under guard in a house in Lüneburg, Himmler bit down on a cyanide capsule that he had hidden in his cheek for weeks and instantly died. He was buried by the British in an unmarked grave in a wooded area near Lüneburg. The location of the grave remains a closely guarded secret to this day.

V-E Day Across the World

In towns, cities, and hamlets across much of the globe, spontaneous V-E (Victory-In-Europe) Day celebrations erupted. Factory whistles blew, church bells pealed, and people piled into and onto cars, buses, taxis, and trolleys, blowing horns, beating drums, and generally making as much joyful noise as possible. Every inch of London’s Trafalgar Square was filled with grateful celebrants, and St. Paul’s Cathedral was packed for the entire day. A large ship moored at the Southampton docks from where part of the Normandy invasion was launched used its horn to blast out the Morse code letter “V” for “Victory”; other nearby ships chimed in.

Winston Churchill, attempting to travel from Number 10 Downing Street to Parliament, found his limousine stuck in a traffic jam of unprecedented proportions; the crowd, most of whom seemed to be trying to shake his hand, actually pushed his car the length of Whitehall.

Like Trafalgar Square, Times Square in New York was a happy sea of humanity as men and women hugged, kissed, waved newspapers that proclaimed victory, and danced in long conga lines. Similar outbursts of joy and relief took place in Moscow, Paris, Sydney, Ottawa, New Delhi, and thousands of other places.

In Joliet, near Chicago, stores, taverns, and government offices closed for the day, but the churches were open for special services.

Hubert Scales, a black U.S. Navy seaman, recalled sailing into San Francisco harbor on V-E Day and being greeted by enthusiastic throngs. “There were so many people, cheering and celebrating our return. I can’t describe the feeling. It was quite a surprise. I didn’t expect to be treated like a hero.”

Not all of the celebrations were peaceful. In Halifax, Nova Scotia, two days of rioting resulted in the deaths of three people and left over 500 businesses damaged.

Despite the gaiety, many felt the celebrations should be subdued, for the job was not over in the Pacific. An Englishwoman wrote in her diary, “As soon as we can get our men home, there will be great joy for those who left their loved ones behind. Some, many, will never return—those who have been lost in this awful fight, we owe our peace to them as well as those who have been saved.”

Servicemen who had survived the war in Europe found their units alerted for the invasion of Japan. To their immense relief, the atomic bomb ended those plans; the almost universal feeling of men scheduled to invade Japan was summed up by an American soldier: “Thank God for Harry Truman.”

The victors took no pity on the vanquished. Joint Chiefs of Staff Directive Number 1067, dated May 11, 1945, spelled out in no uncertain terms how the Allies were to regard their former foe: “Germany is not to be occupied for the purpose of liberation but as a defeated enemy nation.”

WWII’s Enormous Cost

Although defeat in World War I had left the Fatherland unoccupied and undamaged, there was little of the Third Reich that remained recognizable in May 1945. Major cities such as Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg, Dresden, Kassel, Dortmund, Frankfurt, and Nuremburg were anywhere from a half to two-thirds destroyed. The odor of death and destruction hung over the landscape. Berlin, which had had a population of over four million in 1939, had been reduced by nearly half in 1945, due to persons killed in scores of bombing raids and those who had the good sense to flee.

The infrastructure of practically all Germany lay in ruins. It was estimated that across the country thousands of homes, shops, factories, schools, hospitals, castles, museums, bridges, churches, office buildings, railroad stations, and defensive fortifications had been reduced to some 400 million cubic meters of rubble. The highways and railroads were cratered, the electrical, water, and sewer lines were shattered, and virtually all of the services essential for the survival of millions of now homeless citizens had been obliterated.

The overall death toll was staggering. Forty-six million Europeans, including seven million Germans, had perished. At last, however, the terrible violence and destruction that had engulfed almost the entire continent for nearly six years had ceased. The Allies found themselves confronted with a task of Herculean proportions: rebuilding a decimated nation and preventing an even larger human catastrophe.

The Beginnings of the Cold War

Barely had the victory celebrations ended than the Allies began to fall out or, more precisely, than the Soviets parted ways with the Americans, British, and French. With their troops now occupying Austria, Hungary, Poland, Czechoslovakia, the eastern half of Germany, and elsewhere, the Russians saw no need to free the countries under their control or to cooperate any longer with their Western allies. Tensions between East and West grew by the day; by the end of 1945, eastern Germany was firmly in the grip of its totalitarian masters.

Berlin, 80 miles inside the Russian-controlled border, was an island divided into four zones; the Soviets controlled the eastern half while the U.S., British, and French divided the western half into three sectors. To counter the Soviets and forestall any aggressive designs on the part of the Communists, the Americans realized they would need to befriend their former enemies. On June 5, 1947, former Army Chief of Staff and now Secretary of State George C. Marshall announced a $15 billion reconstruction package for Germany and other war-ravaged parts of Europe. It was a bold and necessary move.

On June 24, 1948, the Russians cut off access between East and West Berlin in hopes of driving out the Western powers; the Allies responded with an airlift—with an average of one cargo plane full of food, coal, and other essentials to keep the citizens alive—landing every 45 seconds. After 11 months, seeing that American resolve could not be broken, the Soviets relented and once again allowed vehicles, ships, and trains to cross through their territory into West Berlin. In 1961, the Soviets built the infamous Berlin Wall that halted the continuous clandestine emigration of East Germans into the West.

In 1919, President Woodrow Wilson had pronounced the world’s hope that the Great War would be “the war to end all wars,” but the injustices and bitter residue left over from that conflict ensured that another war of even greater magnitude and tragedy would follow.

Franklin Delano Roosevelt never lived to see the peace he had helped bring about. Nor did he have the chance to deliver a speech, scheduled to be heard at the annual Jefferson Day dinner in Washington on April 13, that expressed the hopes and dreams of all mankind: “More than an end to war, we want an end to the beginnings of all wars. Yes, an end to this brutal, inhuman, and thoroughly impractical method of settling the differences between governments.”

Sixty years later, his dream, and Wilson’s, has yet to be realized.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments