By John Brown

By early April 1941, Lt. Gen. Erwin Rommel’s German Afrika Korps, combined with Italian units, had cleared the British from Libya except for the seaport of Tobruk. The Australian 9th Division had fallen back on Tobruk, and General Archibald Wavell, commander of Commonwealth forces in North Africa, asked that Tobruk be held for two months, until he could reorganize and, with reinforcements, go back on the attack.

The Tobruk garrison, commanded by Australian Maj. Gen. Leslie Morshead, comprised Morshead’s Australian 9th Division of three brigades of infantry plus the 18th Brigade of the Australian 7th Division, together with the British 3rd Armored Brigade and four regiments of British gunners—field artillery, antitank, and antiaircraft. There were also several thousand base troops—British, Australian, Indian, and others—31,000 men in all, 24,000 of them combat troops.

On April 12, Rommel mounted his first attack on Tobruk. It was driven back. From then on he attacked again and again, but Tobruk held, not for two months but for eight months.

A year earlier, from May 28 to June 4, 1940, a crippled British Expeditionary Force landed back in England from the beaches of Dunkirk. A week later Prime Minister Winston Churchill, determined that the British Army would not lapse into the defensive mentality that had led to the collapse of France, sanctioned the raising of a dozen self-contained, specially trained, and well-equipped raiding units of up to 1,000 men each to harry the Germans along the Channel coast. At that stage, it was the only way the British Army could fight.

Clarke’s Commandos

The task of organizing these units was given to Lt. Col. Dudley Clarke, a Royal Artillery officer gifted with unusual imagination. Imagination was in short supply at the beginning of World War II, when the officer corps was described as the most hidebound and orthodox in the Empire’s history. Military historian Correlli Barnett noted that the British Army “was an anachronism, peasant levies led by the gentry and aristocracy.”

Clarke realized this. He had grown up in South Africa and served in Palestine in the 1930s during the Arab rebellion where he had seen guerrilla warfare in action. He called his units “Commandos” after the fast-moving Boer guerrilla Kommandos of the South African war and laid down that they must be volunteers, as physically fit as the finest athletes, trained to the highest standards in the use of infantry weapons, and capable of killing or capturing the enemy quickly and silently. They would operate in darkness more than daylight, be able to work in small groups and individually, think independently, and use their initiative. “The commando,” he declared, “should think of warfare solely in terms of attack.”

Several commando units were raised in England and one in Scotland, the 11 (Scottish) Commando. Its commander was Lt. Col. Dick Pedder, a 35-year-old martinet from the Highland Light Infantry. Its establishment included 10 troops of 50 men, each with a commander and one or two other officers. One of the troop commanders was Captain Geoffrey Keyes of the Royal Scots Greys. Keyes was not obvious commando material, but he had a valuable asset. His father was Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger John Brownlow Keyes, a lifelong friend of Prime Minister Churchill.

Geoffrey Keyes had never been physically robust, and his poor eyesight had precluded his entry into the Royal Navy, to which he had aspired. His hearing was also deficient, and he had been forced to give up boxing and rowing during college at Eton due to potential damage to his ears and curvature of the spine. Already disappointed that his son had failed to follow him in the Navy, Admiral Keyes was further dismayed with Geoffrey’s commission in the Royal Scots Greys, whose officers were typically the sons of businessmen, instead of the elitist Life Guards.

Winston Churchill had brought Sir Roger Keyes out of retirement to become director of combined operations, with responsibility for the recruitment and deployment of commandos. One of his first acts as DCO had been to wire Scottish Command to request that his son, acting Captain Geoffrey Keyes, be transferred from the Greys to the new commando force. Geoffrey was quickly inducted into 11 Commando.

First Actions For the Commandos

Training was ruthless. Many volunteers, officers and other ranks, could not make it and were returned to the units from which they came. Geoffrey Keyes was one casualty. He fell out on a 100-mile forced march in full battle kit but was saved by virtue of his social position. He went on to commando training in earnest: advanced field craft, infiltration behind enemy lines, street fighting, silent killing, navigation and route selection, and training in night sense and night confidence—revolutionary stuff for soldiers of the British Army of 1940.

Toward the end of January 1941, 11 Commando was combined with 7 and 8 Commandos and part of 3 Commando into a brigade, 1,500 men in all; the commander of 8 Commando, Lt. Col. Robert (Bob) Laycock, was appointed acting brigadier. Laycock belonged to the old school of officer privilege. His officers in 8 Commando were all from the right schools and belonged to the right London clubs. They included Winston Churchill’s son, Randolph. The brigade sailed for Egypt at the end of January and arrived at Suez on March 7.

In April, 11 Commando was deployed on Cyprus while the rest of the brigade was sent to Crete to try to contain the German assault on the island. By the end of that battle, more than 600 of the 800 commandos under Laycock’s command were killed or captured. Of the 156 who escaped, 23 were officers, including Laycock.

In early June, the 485 men of 11 Commando left Cyprus by ship to take part in the invasion of Vichy French-held Syria. Keyes was now second in command.

The commandos’ task was to capture French positions on the Litani River and hold them long enough for the 21st Australian Infantry Brigade, advancing from Palestine to the south, to reach the river and build a pontoon bridge over it. The landing on the beaches just north of the mouth of the Litani River was delayed, and instead of landing in the dark it was made after dawn in full view of the French and under fire from their guns. It was 11 Commando’s baptism of fire.

The commandos captured all the French positions and linked up with the Australians, but the price was heavy. Of the 379 men who actually landed, 130 were casualties, including the commander, Lt. Col. Richard Pedder, who was shot dead. Throughout the action, Keyes performed well. He was awarded a Military Cross. The commandos returned to Cyprus, which was still under threat of invasion, with Keyes promoted to acting lieutenant colonel and commanding in place of Pedder.

Rommel’s Obsession With Tobruk

Throughout the summer of 1941, Rommel built up his forces and supplies and continued his attacks on Tobruk while the British, commanded now by Lt. Gen. Sir Claude Auchinleck, who had replaced Wavell, were building up the Eighth Army with the intention of invading Libya and relieving Tobruk in November.

By now Rommel’s name had made headlines. He was becoming legendary, not only among his own forces but also among the British where, as one soldier commented, “We all thought he was a bloody good bloke.”

This “Rommel cult” among his own troops worried Auchinleck; not only did they think more highly of the German general than of their own generals, they also regarded his ability to run rings around them as humorous. Auchinleck, therefore, sent out a directive to all his commanders: “I wish you to dispel by all possible means the idea that Rommel represents anything more than an ordinary German general. The important thing now is to see to it that we do not always talk of Rommel when we mean the enemy in Libya. We must refer to ‘the Germans’ or ‘the Axis powers’ or ‘the enemy’ and not always keep harping on Rommel.”

What Auchinleck feared most was that Rommel would take Tobruk. With Tobruk behind him as a supply base, the German general could push directly into Egypt, seize Alexandria, Cairo and the Suez Canal, and battle into Palestine, Syria, and the oilfields of the Gulf. Rommel was, in fact, planning just that.

Rommel flew to Germany at the end of July to present his plan to Hitler and his top commanders. The plan was rejected. Hitler was preoccupied with the war in Russia and considered the campaign in North Africa of minor importance. He believed the British would begin an offensive in Libya in the latter part of the year, and Rommel’s priority must be to repulse such an offensive. When that was done, he could safely take out Tobruk.

But Rommel was obsessed with Tobruk. He was convinced that Auchinleck would not mount an offensive in Libya until the outcome of the Russian campaign was decided. However, Hitler was right. Auchinleck was planning a major offensive in Libya for November. The British commander knew through Ultra intercepts of German coded messages that Rommel was planning a major attack on Tobruk. He must have wondered how he could get rid of his German opponent but was too much of an officer and gentleman to think of direct action.

Keyes’ Plan to Eliminate Rommel

In August 1941, 11 Commando moved from Cyprus to Egypt to begin the process of disbandment, returning some officers and men to their parent units, some to special forces such as the Long Range Desert Group (LRDG) or the fledgling Special Air Service and Special Boat Service (SBS). Keyes, now age 24 and determined to hang on to some of his commandos and do something to show he was worthy of his promotion to lieutenant colonel, obtained permission through his father to retain a small cadre of 110 volunteers while he looked around for something to do that would vindicate the existence of his unit.

In September, Keyes heard from an officer he had known in the Royal Scots Greys who was now with the Special Operations Executive (SOE) that Rommel had been seen by Arab agents at an Afrika Korps headquarters in Beda Littoria on the escarpment of the Jebel al-Akhdar, 18 miles inland from the Cyrenaica coast of Libya. Beda Littoria was 250 miles behind the German-Italian lines but, landed from the sea, a commando unit could strike quickly at the headquarters and destroy it, even take Rommel prisoner or kill him.

In early October, Keyes went to see Lt. Gen. Sir Alan Cunningham, commander of the Commonwealth Western Desert Forces, at his headquarters near Alexandria. Keyes’s father was a personal friend of Cunningham’s brother, Sir Andrew, commander of the Mediterranean Fleet, and of Winston Churchill, so the extremely busy general made time to see the unlikely looking commander of 11 Commando.

Keyes laid out his plan to decapitate the German-Italian forces by capturing or killing Rommel and destroying his headquarters. Cunningham was impressed; if the raid were successful it would demolish the Rommel cult, boost British morale, and cause confusion at the beginning of planned November offensive. He said he was in favor of the plan and would look into it. Keyes was elated. He told his 21-year-old adjutant Tommy Macpherson, “If we get this job, it is one people will remember us by.”

Compromised Reconnaissance

Captain John “Jock” Haselden was one of a dozen SOE agents operating behind enemy lines in Libya. These agents were taken into Libya and brought out by contingents of the LRDG. Haselden, born and raised in Egypt of an English father and Egyptian mother and schooled in England, was fluent in a number of Arabic dialects and in French and Italian. In manner, he was the typical Englishman, but with his swarthy good looks and dark eyes inherited from his mother and his fluency in Arabic he could pass easily as an Arab.

Haselden was an outstanding operative, and many stories about him were passed around. One contemporary remembered “how he would wander into Italian-occupied towns disguised as an Italian officer; how, dressed as a Bedouin and with a radio under a blanket beside him, he would sit by the roadside counting vehicles in Italian convoys; how he once drove a flock of sheep over an Axis airstrip under the eyes of Italian guards to pace out its dimensions.”

In October, Haselden and an Arab NCO from the Libyan Arab Force were in the hills and ridges of Cyrenaica’s Jebel al-Akhdar. One of his agents in the town of Slant confirmed previous intelligence reports that Rommel had been seen using a headquarters in the town of Sidi Rafa, now named Beda Littoria by the Italians, and using a villa half a mile away as a home.

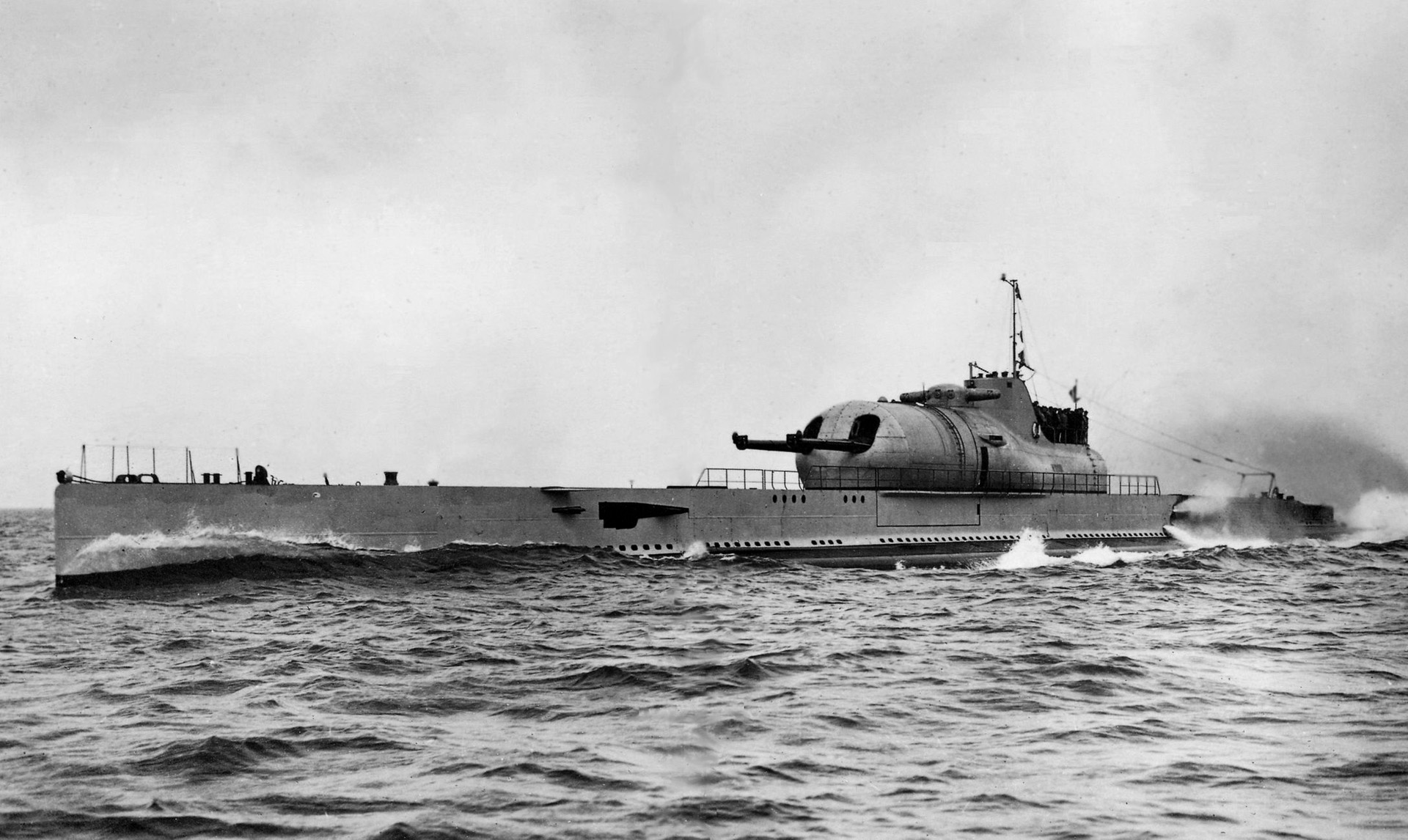

While Haselden was still in the Jebel al-Akhdar, Tommy Macpherson went in by submarine to reconnoiter a beach in Cyrenaica for a commando landing to take place in three weeks’ time and to check a night route up the escarpment of the Jebel, roughly a mile from the beach. Two officers and an NCO from the SBS accompanied him.

A few nights later, the submarine surfaced three miles off Ras Hilal, one of the two sites marked for Keyes’s landing. The team went in aboard two canoes and found a route up the escarpment of the Jebel, but when they returned to the rendezvous point, the submarine did not appear for the pickup. It did not appear the next night, or the next. A navigation error had put the submarine in the wrong bay.

The team hid its canoes near the beach and began the long walk to Tobruk. Close to Derna, the British were captured by an Italian patrol. Another Italian patrol had found their canoes at Ras Hilal. Although they did not talk under interrogation, it was obvious they had been on a reconnaissance for some future operation. A landing by Keyes and his commandos at Ras Hilal was now compromised.

Bob Laycock: “A Bullshitter of the Highest Order”

The British invasion of Libya, Operation Crusader, was scheduled to begin on November 18. General Cunningham planned to lure Rommel into a trap where his forces would be decimated by much superior numbers of British tanks. He had included in his battle plan two operations by commandos. One was to be by 60 commandos of David Stirling’s parachute unit, the forerunner of the SAS, who would on the night of the 17th drop near five enemy airfields in Cyrenaica and destroy as many aircraft as possible with incendiary bombs.

The drop was made in high winds and an electrical storm in which many of the containers carrying equipment, explosives, detonators, and fuses were blown across the desert. Many of the commandos had sustained broken bones and lacerations on landing, others were carried away by their canopies and dispersed, and one man was never seen again. The operation was a failure.

The other was Keyes’s amphibious operation, code-named Flipper and timed to coincide with Stirling’s airdrop. This would destroy the German headquarters and communications at Beda Littoria and, if possible, take out Rommel.

While Keyes was delighted with his chance for glory, his commanding officer, Brigadier Bob Laycock, was not enthusiastic. He noted that if the raiding party did capture Rommel the Germans would be in hot pursuit and they stood almost no chance of being evacuated. The attack, even if successful, meant almost certain death for those who took part in it.

Laycock had already decided to accompany the operation as an observer and to hold the beach while Keyes led the attack. Under a cloud for his action on Crete six months earlier, Laycock hoped that being involved in the operation would help salvage his reputation.

Before leaving for the Jebel al-Akhdar, Tommy Macpherson noted, “Laycock was in our eyes a society cavalryman with a close and exclusive interest in his own career; he was a bullshitter of the highest order. For him the Rommel raid was a no-lose situation. If it was successful then by going along he would get credit, and if it wasn’t, then by staying on the beach he would almost certainly be in a position to get out.”

When the submarine returned to Alexandria without Tommy Macpherson and the SBS men, it was assumed they were captured or dead and the Ras Hilal landing site could not be used. Keyes decided that the landing would take place at his second choice, Khashm al-Kalb. When Laycock stated his reservations, Keyes asked him not to repeat them in front of General Cunningham as he might cancel the operation.

18 Miles to Rommel’s Camp

On November 7, Jock Haselden and three other SOE agents, all in Arab dress, and two Senussi Arabs of the Libyan Arab Force were taken by a patrol of the LRDG into the Jebel al-Akhdar. The vehicles were hidden about 20 miles from Mekili, and Haselden went on alone to Slonta, where he met with his agent. From there, with a guide provided by his agent, he set off for Khashm al-Kalb, the beach where Keyes and his commandos would make their landing.

In the late afternoon of November 10, two submarines, the Torbay and Talisman, left Alexandria harbor and headed for the Cyrenaica coast. Crammed into them were Keyes and Laycock and 57 commandos and eight SBS men. With their arms, equipment, explosives, and supplies and 28 rubber dinghies and four SBS canoes called folbots, there was little room to spare.

On November 12, Keyes called the commandos in Torbay together. Laycock was in the Talisman. The commandos already knew that the operation was intended to inflict maximum damage on an enemy headquarters, installations, and communications and that it involved four primary tasks to be carried out by four detachments.

Detachment 4, commanded by Jock Haselden, who would meet up with the landing party from the submarines and then rejoin his SOE agents and Libyan Arab Force NCOs, would sabotage communications at the headquarters of the Italian Trieste Division near Slonta. Detachment 3, 12 commandos under Lieutenant David Sutherland, would attack the Italian headquarters at Cyrene and destroy the communications cable mast at the Cyrene crossroads. Detachment 2, 11 commandos commanded by a Lieutenant Chevalier, would sabotage the wireless station and the Italian Intelligence Center at Apollonia. Detachment 1, including two officers and 22 commandos led by Keyes, would hike the 18 miles over the escarpment to Beda Littoria and assault the Afrika Korps headquarters.

In the submarine, Keyes now revealed the unknown part of their mission: to capture or kill Rommel. In stunned silence, he added, “If he comes quietly, we’ll bring him along. If he doesn’t, we’ll knock him off.”

Keyes was too realistic to suppose a man like Rommel could be captured and marched 18 miles across country to embark on a submarine. He would have to be killed. His men quickly realized this, too, and a number of them cursed quietly. It was a suicide mission. Keyes himself did not expect to get back from the operation.

Commandos at Beda Littoria

On November 13 and 14, the two submarines examined the landing beach at Khashm al-Kalb through their periscopes. After lunch on the 14th, the commandos cleaned and oiled their weapons—.303 Lee Enfield rifles, Bren guns, Thompson submachine guns, pistols, and daggers—and checked their equipment and ammunition. Then they rested while the sailors stacked tins of gelignite, rations, and water below the gun tower hatch.

At dusk the submarines surfaced in rough seas and rising winds, heralding late autumn storms that would bring the worst cloudbursts in 60 years. Then, in response to a signal light from Haselden on the beach, Torbay moved in closer while commandos and sailors climbed out on to the submarine’s deck and began inflating the dinghies and loading them.

In winds and heaving seas, men and dinghies were swept off the submarine and had to be hauled back. What should have been an hour’s routine takeoff became nearly a six-hour nightmare. Finally, half an hour past midnight, Keyes signaled Talisman from the beach that, except for two who did not make it, his group had landed. Talisman then struggled inshore, but by 4 am only Laycock and a dozen commandos had managed to land.

With the commando landing under way, Haselden left to rejoin his group and sabotage communications near Slonta. This operation was carried out successfully, and the group was picked up by the LRDG.

The commandos moved off the beach to hide in a wadi, a scrub-flanked gully, where, wet and shivering, they waited out the rest of the night and the next day. Because little more than half their number had made it ashore, Keyes and Laycock modified the orders for the operation. Instead of three detachments of commandos striking at three targets, now there would only be two detachments and two targets. Keyes would lead the main force against Rommel’s headquarters while Lieutenant Roy Cooke led six commandos to sever telephone and telegraph lines at the crossroads south of Cyrene. Laycock would remain at the wadi with three commandos to guard supplies and secure the beach for evacuation.

That evening, as Keyes briefed the men and handed out gelignite and ammunition, the sky became overcast, it began to rain, and the temperature dropped. For a second time, Laycock advised Keyes to delegate the job of leading the raid to a junior officer, but Keyes refused. He appeared confident and cheerful as, at 8 pm in pouring rain, they set off into the black night.

Keyes’s heavily laden assault force, following a local guide provided by Haselden, climbed the two steep terraces up to 1,200 feet. When they reached the top, the guide refused to go any farther and disappeared into the night.

They hid out during the day in a cave about five miles from Beda Littoria. It rained all day, and the commandos shivered in their sodden uniforms. When darkness fell, they were glad to get moving again even though the weather worsened. The rain was now coming down in torrents, winds blew bitterly cold, thunder rolled, and lightning streaked the sky. The goat tracks were liquid mud. Finally, in flashes of lightning they could see an Arab village and beyond it the outline of a large building, the German headquarters. They had reached Beda Littoria; it was nearly midnight.

A Late Coded Message

The commandos halted while Keyes surveyed the scene in the lightning flashes. Beyond the Arab village and market, a low hedge and a barbed-wire fence surrounded the building. To its left was another building, the town hall, and behind that was the carabinieri barracks. Nearby were a grain tower and a number of small Italian villas.

They moved in closer until they were among some Arab dwellings 100 yards from the headquarters, a six-floor building with lights showing on some of the floors. Taking one of the commandos with him, Keyes went off on a reconnaissance of the building; the others waited in the pouring rain. When they returned, Keyes sent Lieutenant Cooke and his detachment to wreck the communications near Cyrene and gave his instructions for the assault on the headquarters.

Four commandos were to head to the transport pool to cover the assault party from outside the grounds; seven commandos spaced themselves around the perimeter of the building to kill anyone who came out of it through the windows. Keyes and three commandos would, covered by two more commandos, go in through the front door and carry out the assault. When it was over, explosive charges would be set around the building, power plant, and transport pool, and everyone would retreat to the Arab dwellings and from there fall back to the wadi at the beach.

At about this time, midnight on November 17, a coded message from London was received in Cairo advising that General Rommel was on his way back to Libya from Rome, where he had spent the past three weeks. Even if Rommel had returned to Libya earlier than that, he would not have been at Beda Littoria. The headquarters Keyes had reconnoitered was actually that of a Colonel Schleusener, the chief quartermaster of Panzergruppe Afrika.

Rommel had apparently visited the site sometime in September, but his operational headquarters was close to Tobruk. The chief quartermaster, who was in the hospital at the time of Keyes’s assault, and the chief medical officer at the headquarters were both of the same build as Rommel and wore the same type of uniform. Either could easily have been mistaken for Rommel by Haselden’s spies. Rommel actually returned to his headquarters near Tobruk late on the 18th.

It is now known that the SOE had learned through Ultra on November 2 that Rommel had left for Rome, and by November 14, when the commandos were last in contact with Cairo, no word of his return had been received. This information was not passed to Keyes.

Assault on the German Camp

There are several conflicting accounts, both British and German, of what went on during the assault on the German building. What apparently happened was that Keyes and his three commandos, covered by the other two, went in through the front door. Inside, Keyes found himself faced by a German guard. Keyes pointed his pistol at him but hesitated to shoot him, probably not wanting to alert the rest of the occupants of the building. The German deflected Keyes pistol and shouted warnings as they struggled furiously while the commandos behind Keyes could not get around him to stab the German. As the noise being made by now was alerting the Germans, Keyes’ second in command, Captain Robert Campbell, shot the German with his pistol.

Keyes then moved to the open door of an office and fired two shots from his pistol into the room. Beside him, one of the commandos fired a burst from a Thompson submachine gun into the room. Then Keyes fell back, hit by one bullet. A commando threw a grenade into the room, and they dragged Keyes outside. He was dead.

The German occupants were now awake and beginning to use weapons. A burst of fire at the back of the building sent Campbell, thinking it might be Rommel escaping, running around the outside until he was shot in the right leg, most likely by one of his own men.

At the back of the building, where several commandos were trying to break in, a German lieutenant jumped out of one of the windows and was shot dead. The commandos were unable to break in and missed the opportunity to destroy all the documentation concerned with Rommel’s logistics. This would have been a serious blow for Rommel.

With one officer dead and the other out of action, Sergeant Jack Terry was trying to reorganize the commandos. At the transport pool the commando detachment was trying to blow up vehicles, but the wet detonators and timers for their explosives would not work. The commandos had better luck with the generator; they put it out of action with explosives set off by grenades. As guards from the nearby barracks began to move in, Terry ordered the commandos to regroup at the Arab dwellings prior to withdrawing to the beach.

The commandos wanted to carry the wounded Captain Campbell back to the beach, but he refused to be carried.

The Axis Manhunt

The commandos began their withdrawal, but only a mile from Beda Littoria Terry decided that to go any further and attempt to descend the escarpment in the dark and rain was foolhardy. So they spent the rest of the night huddled together and soaked to the skin. Still believing that Rommel had been in the building and that they had failed to capture or kill him, depression added to their discomfort.

Ten miles from Beda Littoria, at the crossroads a mile from Cyrene, Lieutenant Cooke and his commandos studied the cable mast they were to destroy: four massive wooden posts supporting an array of terminals and wiring with lines going off in four directions to Derna, Slonta, Bardia, and Benghazi. Some of the commandos climbed the posts and cut wires so that when they destroyed the posts the structure would fall, but when they came to blow up the posts they found that the fuses for the explosives were wet and useless. Finally, using grenades as fuses, they managed to create some explosions, but they were not enough to put the site out of action permanently.

The next day, the commandos hid in a cave while Italian and German troops with tracker dogs searched for them. Two Italian soldiers entered the cave. The commandos shot one of them but the other, wounded, raised the alarm. Grenades were thrown into the cave, and the commandos decided to make a break for it. They raced out of the cave and found themselves facing two heavy machine guns. It was hopeless. They put up their hands. They were taken as prisoners to Benghazi.

Back at Beda Littoria, the wounded Captain Campbell was interrogated by the Germans but would say nothing. He was given medical treatment and sent to a hospital in Derna. On November 19, Keyes and the four Germans killed in the raid were buried with full military honors in the local churchyard.

Sergeant Jack Terry and his commandos descended the escarpment and rendezvoused with Colonel Laycock and his commandos in the wadi near the beach. Twelve commandos, including Roy Cooke’s group, were still missing.

Three Commandos Return

The submarine Talisman, unable to land its full complement of commandos, had returned to Alexandria, but Torbay had remained in place off the headland. That night Laycock contacted Torbay by Aldis lamp, but the sea was too rough for the commandos to be ferried out to the submarine that night.

Around noon the next day, the commandos came under fire from a large group of Italian carabinieri. After a couple of hours of sporadic firing and knowing the Italians would have called up reinforcements, Laycock gave the order to go into escape and evasion—every man for himself. They broke away in small groups, leaving behind one wounded man and a medical orderly.

The Italian and German manhunt for the commandos was not very successful until, with a price on their heads, all the British except Colonel Laycock and Sergeant Jack Terry were betrayed by local people. They were befriended by Senussi tribesmen at different times and survived for more than a month until on Christmas Day 1941, they met with forward troops of the British Eighth Army near Cyrene. Laycock, Terry, and a SBS man who had survived alone in the Jebel were the only ones to return safely from the abortive mission to capture or kill Rommel.

On his return to Cairo, Laycock recommended both Geoffrey Keyes and Jack Terry for the Victoria Cross. The dead Lt. Col. Keyes, son of an admiral of the fleet, was granted the award, but the 19-year-old Sergeant Terry, a butcher’s son, who had faced the same odds as Keyes and brought the commandos back to the beach, was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal.

When Rommel heard about the raid on the headquarters at Beda Littoria, he was deeply indignant, muttering words to the effect: “How could the British have ever imagined I would have my operational headquarters 250 miles behind my own front line?”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments