By David H. Lippman

“Maleme. 20th May, 1941. Usual Mediterranean summer day. Cloudless sky, no wind, extreme visibility; e.g., details on mountains 20 miles to the southeast easily discernible.”

So opened the war diary of the 22nd Battalion, 2nd New Zealand Division. The battalion’s official historian, Jim Henderson, would write later, “Of all the days of the war one stands alone in the minds of the battalion. The day is 20 May at Maleme, Crete.”

The 22nd Battalion was one of four battalions of the 5th New Zealand Brigade assigned to defend the extreme west of the British and Commonwealth defenses on the island of Crete. Under its tall, austere, professional commander, Colonel Les Andrew, who held a 1918 Victoria Cross, 22nd Battalion held the most important part of the Maleme sector of defense, Maleme Airfield, the key to the rugged island. The airfield would become the epicenter of the battle.

Crete: An Opportunity and a Menace

In April 1941, Adolf Hitler came to the aid of his beleaguered Italian ally, Benito Mussolini, whose misplanned invasion of Greece had bogged down in that nation’s mountain winter. On April 6, the German panzers plunged into Greece through Yugoslavia, turning the Metaxas Line, crushing the Greek defenders and their British Commonwealth allies, and forcing the British to evacuate.

Most of the troops that came stumbling back from the Greek debacle were dumped on the island of Crete to reorganize and regroup. Both sides saw Crete as an opportunity and a menace.

Both sides saw the potential of the island as a forward base for advances or attacks against their opponents. Both saw the potential of the island as a base for enemy forces. But the British held it with a mixed garrison of British, Australian, and New Zealand troops numbering about 40,000 men including 11,000 Greek soldiers, all poorly armed. Among the Greek troops was King George of the Hellenes, whose royal person had to be protected from German capture, lest the Nazis score yet another propaganda victory.

The British defenders were not in much better shape. As at Dunkirk, the retreating British had left a great deal of supplies and transport behind in Greece, and some of their outfits included composite battalions of artillerymen without guns, supply troops without trucks, and various rear-echelon paper chasers who had been handed rifles and told to fight. General Sir Archibald Wavell, in command of the Middle Eastern Theater, reviewed the situation on Crete and scraped up six battered Matilda tanks from his workshops and 75 captured Italian artillery pieces—all lacking sights—to send to Crete.

Intercepting the Airborne Plan

To command this mixed force, Wavell appointed the head of the 2nd New Zealand Division, Lt. Gen. Sir Bernard Freyberg, another World War I Victoria Cross recipient, who was well regarded as a determined and pugnacious fighter if not a great strategist. His firm nature seemed perfect to hold Crete’s rocky terrain.

Freyberg also held a priceless advantage. Thanks to Britain’s codebreaking efforts and the overly chatty Luftwaffe radio net, he knew the entire German plan for the invasion of Crete and could spot his troops accordingly, which he did. British troops were posted to the airfield at Heraklion in the east, Australians to Retimo in the center, and New Zealanders to hold the critical area between the Suda Bay port and Maleme Airfield in the west.

That German plan was one that had been whipped up in a short time by one of Germany’s most revolutionary soldiers, Lt. Gen. Kurt Student, commander of Germany’s airborne arm. He saw in the Cretan situation an opportunity to prove the ability and worth of the Nazi parachute arm, which consisted of Hitler’s bravest and best-trained troops.

So far the parachute arm had enjoyed a small but good war, taking key points in Norway, dropping behind Dutch lines, and overrunning the Eben Emael fortress in Belgium. Now Student wanted to use his battle-hardened 7th Parachute Division in a mass drop on Crete, taking the island by storm.

The plan was simple enough. His four regiments would drop on the island at four places: Retimo, Heraklion, Canea and Suda, and Maleme. The 11,000 paratroopers would seize the airfields and ports, enabling 12,000 more troops to land from the air and sea to finish the job of taking the island. The Luftwaffe’s “flying artillery” would cover the entire operation. The daring nature of the plan and its use of shock and speed appealed to Hitler, who approved the plan as a necessary prerequisite to covering his flank for the invasion of Russia.

But the plans ran into trouble right away. German intelligence underestimated the British defenses, believing there to be only 5,000 men on the island. There were not enough planes to deliver the paratroopers to their drop zones all at once—the Luftwaffe would have to make three shuttle flights on the invasion day to get all the paratroopers to their targets. And the paratroopers, lightly armed and short of supplies, would have to take their ports and airfields in a very short time or they would be isolated and helpless.

Still, Student had great faith in his men, and the whole operation, codenamed Mercury, got started on May 20, with paratroopers boarding their trimotored Junkers Ju-52 transports before dawn, wearing heavy camouflage uniforms in the hot Mediterranean sun. The planes took off from their dusty airfields in quick order.

A paratrooper wrote, “Dawn came and went. We flew on until below us we could see the dun-colored, inhospitable-looking terrain with mountains blinding white in the sunlight. These peaks ran along the length of the island like a spine. Pillars of black smoke rose still and straight into the blue sky. The Luftwaffe had been softening up the enemy and destroying his opposition.”

“The Earth Shook With Explosions”

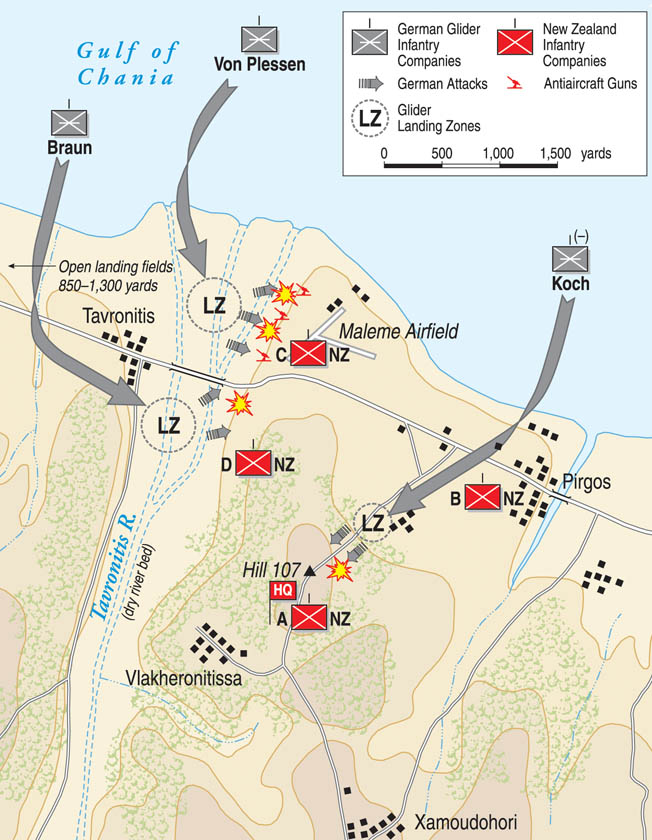

Meanwhile, the British had been digging in. With everything in short supply except determination, the 5th New Zealand Brigade, under Brigadier James Hargest, drew the defense of Maleme. The 22nd Battalion was assigned the airfield, and Colonel Andrew deployed C Company directly on it, the Headquarters Company just east of it, and A Company directly on the high ground that dominated the airfield, Hill 107, with B Company south of that. Andrew also had control of two of the Matilda tanks of the 7th Royal Tank Regiment which had been assigned to Crete, but he did not control the Royal Air Force and Fleet Air Arm parties left behind on Maleme Airfield—they even had different passwords and countersigns. In all, Andrew had to worry about 14 different commands in his small area, including Australian antiaircraft gunners and Royal Marines.

The terrain was rocky and hilly, but the defenders lacked any sort of air cover. The last Hawker Hurricane fighters had already been pulled out. The Luftwaffe’s Junkers Ju-87 Stuka dive-bombers and Messerschmitt Me-109 fighters dominated the skies over Crete, constantly bombing and strafing the British positions, knocking out hastily laid telephone lines, and disrupting communications.

The German attack on Maleme was assigned to the Assault Regiment, a mostly glider-borne outfit, which would land one force of 500 men under Major Walter von Braun west of the Tavronitis River, seize the bridge over the nearly dry river, and attack the airfield from the west. Another force, under Lieutenant Wulff Von Plessen, was to land at the river mouth and destroy the defenses there, and a third, under Major Walter Koch, the victor of Eben Emael, was to land on the slopes of Hill 107 and take it. The rest of the force assigned to Maleme, 2,000 men, would parachute well clear of the defenses, form up, and come rapidly to support the glider men. The whole command, named Task Force Komet, was a powerful unit, relying on speed, firepower, and surprise to take the airfield.

As the sun rose over Maleme Airfield that morning, the Luftwaffe arrived to deliver what everyone now called the “morning hate,” but this time the German airmen concentrated their bombing and strafing on the area around the airfield, strafing olive groves and making it impossible for troops on the ground to move more than a yard or two from their slit trenches.

At least 24 heavy bombers roared over the 22nd Battalion, dropping their ordnance. “Dust and smoke billowed up; the earth shook with explosions; trees splintered; slit trenches caved in,” wrote the official historian. In one substantial five-man trench, only Sergeant Joe Chittenden, a Waitara baker, survived.

“Just Like the Duck Shooting Season!”

“The silence after the blitz,” wrote Sergeant A.M. Sargeson, a Hawera clerk, “was eerie, acrid, and ominous.”

“So accustomed to the ‘daily hate,’ that as soon as the planes disappeared out to sea the men began to move to breakfast which had been cooking during the raid,” the battalion’s history recorded. Many of the RAF fitters did not bother to take their rifles with them to breakfast.

“Then, in the middle of a scurrying breakfast,” wrote official historian Dan Davin, “There was a new note: a distant buzz, like the sound of a swarm of enormous hornets, rising to a crescendo of drumming, throbbing sound, loud above the incessant din of machine-gun fire. Looking up, mess-tins in hand, New Zealanders saw the sky so full of great transport planes that it seemed impossible they should not crash into one another. And, even as they watched, the air was full of parachutes dropping from the aircraft and flowering like bubbles from a child’s pipe, but infinitely more sinister.”

The New Zealanders opened fire with everything they had, mostly Bren machine guns and rifles, aiming at the falling parachutes.

Unlike their American and British counterparts, German paratroopers came to earth clutching only a knife and pistol. Their rifles came in a canister with the stick of paratroopers. German paratroopers were expected to “roll up the stick” and break out the rifles from their canisters. As a result, they were most vulnerable as they were hitting the ground and directly after.

The New Zealanders were impressed but not demoralized by the airborne armada. “Action came as a relief—almost a grim joy—after cowering under cover for a fortnight of air raids, and the remark, ‘Just like the duck shooting season!’ was widespread at the time,” wrote battalion historian Jim Henderson.

Private N.N. Fellows, a Wellington salesman, wrote, “The first thing that met my startled gaze when I looked out was the descending paratroopers. My throat seemed to get very dry all of a sudden and I longed for company.”

A German paratrooper, however, had opposing memories: “My parachute had scarcely opened when bullets began spitting past me from all directions. It had felt so splendid just before to jump in sunlight over such wonderful countryside, but my feelings suddenly changed. All I could do was to pull my head in and cover my face with my arms.”

The Kiwis slaughtered scores of paratroopers as they came hurtling to the ground.

Gliders Landing Under Fire

At Maleme the gliders came swooshing in. Everyone watching was amazed at the strange new planes that lacked engines but were headed straight for their positions. Then people yelled, “Gliders,” almost in unison.

Von Plessen’s gliders swooped in over the northern coast of Crete, did a semicircle, and came in from behind the New Zealand antiaircraft positions. One glider was hit by tracer bullets while still in flight and crashed, bursting into flames. The paratroopers inside leaped out of the glider’s windows, their uniforms aflame. Another glider was hit point-blank by a British antiaircraft gun at zero elevation. It disintegrated, spewing pieces in all directions.

As soon as they came to a halt, the Germans inside the gliders began spilling out to take their objectives. Plessen’s detachment attacked the antiaircraft gun crews by the river mouth and overwhelmed them. At close range, the Bofors guns were useless, and so were the gunners’ pistols. But then Plessen’s men faced the New Zealanders’ rifles. The New Zealanders stopped the German attack cold. Plessen ordered a withdrawal. As he rose to signal his men, a burst of fire cut him in two. The senior officer attached to this assault group, a Dr. Weizel, assumed command of the detachment and supervised the retreat.

Most gliders landed on the stony riverbed of the Tavronitis, and everyone opened up with small-arms fire, which sounded like a fusillade of firecrackers. Several gliders smashed on the stones of the broad riverbed, injuring their occupants. One bounced off the bridge itself. In at least two cases, accurate New Zealand fire hit the glider pilot, and one glider crashed nose up with the belly striking a rock, breaking the fuselage in half. The only survivor was war correspondent Franz-Peter Weixler in the tail section of the glider.

Some gliders came in too high. One banked very sharply in its descent; its wing dipped low and struck the rocky prominence of a hill. After cartwheeling, the wing crumbled and the fuselage smashed itself against a grove of olive trees. Most of the occupants were killed.

Another 40 gliders landed at the mouth of the Tavronitis and farther up the riverbed, containing the rest of 1st Battalion of the Assault Regiment, the regimental headquarters, and part of the 3rd Battalion. Major Koch’s detachment landed in exposed positions and came under heavy fire. Koch himself was wounded, and the survivors had to crawl their way down toward the Tavronitis Bridge to join their comrades.

Major Koch’s Assault on Hill 107

In his lead glider, Major Koch sat behind the pilot. The glider dipped forward gently, the only sound the hissing of air streaming by the wings. Koch yelled, “Hold tight!” as the glider careened off a stone wall, spun clockwise, and broke in two, coming to a full stop in a cloud of dust. Koch and his men sat there for a moment, realized they were unhurt, and charged out of the glider.

Koch was surprised at what he found. The terrain was more hilly than the reconnaissance photos had led him to believe, and his gliders were scattering among the hills. He sent runners to collect the men and to form his unit into a concentrated body.

Koch got down to business at his command post and soon realized the attack was going poorly. According to the timetable, his glider team was supposed to have captured and secured Hill 107 by now, but of the 150 men in his detachment, only 25 had materialized. Worse, his men were being enfiladed by the New Zealand defenders.

He decided not to wait and attacked with the 25 officers and men of his battalion staff, pushing off toward the summit of Hill 107. They initially hit the RAF tented camp on their side of the slope. According to plan, the RAF men would be caught in their cots. Instead, the cots were empty. “One less problem,” Koch shouted, “On toward the summit!”

The men charged eagerly behind him and into a wall of small-arms fire, which stopped the Germans cold. German paratroopers dived for what cover they could find on the bare hill. Koch was not among them. He took three bullets and was left lying in a hollow beside a bush, nearly dead.

“The Odds Must Have Easily Been 15 to 1”

Captain T.C. Campbell commanding D Company recalled, “My first thought was, ‘This is an airborne landing.’ I still have vivid recollections of the gliders coming down with their quiet swish, swish, dipping down and swishing in.”

With German troops landing in sections between the five New Zealand companies, the battle degenerated into separate actions. Headquarters Company, under Lieutenant G.G. Beavan, consisted of 60 men and faced between 10 and 20 planeloads of parachutists. The Germans suffered severe losses, but with their usual tenacity regrouped and formed strongpoints in the grapevines and trees.

Sergeant Major J. Matheson’s platoon was cut off and overrun, Matheson being killed by a grenade. Regimental Quartermaster Sergeant J. Woods, who was taken prisoner in the battle, described the scene thus: “Over comes the Hun with Stukas, Junkers, and gliders, not mentioning the 109s. By the time the Stukas and 109s had left us the air around seemed to be alive with Junkers, and believe me the birds that flew out of them were pretty thick. They looked impossible as the odds must have easily been 15 to 1.”

After taking Matheson’s position, the Germans got no farther. The Germans tried another attack on the Headquarters Company later in the day but were driven off by a shell from C Troop, 27 New Zealand Battery’s 75mm guns. The gunners had fashioned sights out of wood and mounted them to the captured Italian guns with chewing gum.

Major Braun was killed, but his glider troops had overwhelmed the machine-gun posts east of the river and seized control of the bridge over the Tavronitis.

Flanking the Airfield and Hill 107

The attack also stunned the RAF ground crew at Maleme, left behind when the planes pulled out. Some, still sheltering from the attacks, were afraid to look up. Less fearful (and better-armed) was C Company of 22nd Battalion, whose three platoons engaged anything that came their way. The platoon on the western edge next to the Tavronitis Bridge had to switch fire back and forth between the Plessen group and the Germans on the opposite side of the Tavronitis.

Task Force Komet was commanded by Colonel Eugen Meindl, who at age 51 refused to ride a glider into battle, preferring to jump, to show he was as tough as the youngest second lieutenant. As soon as he hit the ground he grasped the situation with great speed. The New Zealanders were much stronger than anticipated but had nothing west of the Tavronitis River. The airfield was key to German reinforcement and survival, and Hill 107 was key to the airfield. So while Braun’s men kept pushing at the airfield flank, he sent Major Stentzler’s 2nd Battalion on a right-flank maneuver to take Hill 107 from the rear.

But at the same time, Major Koch was struck down with a severe head wound. Koch’s battalion alone would lose 16 officers killed and seven wounded.

The eastern jaw of the German attack on Maleme was the Third Battalion, Assault Regiment, under Major Otto Scherber. These 600 men were dropped by 58 transports between the villages of Pirgos and Platanias along the coast road. Once landed, the paratroopers were to consolidate, then advance on the airstrip from the east.

The transports crossed the coast and came under massive flak as they approached the drop zone. Black transport planes turned into huge orange fireballs, yet the survivors held their course. At 400 feet, the planes were low enough to avoid the fire of the 3-inch antiaircraft guns and drop their paratroopers, doing so at 7:35 am, five minutes behind schedule.

First Lieutenant Walter Schiller made an uneventful descent from his Ju-52 over a quiet sector. As he drifted to earth, he studied the terrain. It bore no resemblance to his maps. His drop had gone off course. But he saw smoke four miles away and figured that was Maleme Airfield.

Most of the 10th Company of Scherber’s Third Battalion dropped halfway between Maleme and Platanias, expecting to find a quiet area in which to consolidate and move west. Instead, they drew concentrated fire from one of the odder outfits in the British order of battle, the Field Punishment Center.

Crete during airborne operations on May 21, 1941, a Junkers Ju-52 transport plane leaves a trail of smoke and flame following a hit by accurate antiaircraft fire from British defenders on the ground.

Battle at the Field Punishment Center

Under the command of Lieutenant W.J.T. Roach, the FPC was the field jail for the British garrison’s “plonk artists,” deserters, and thieves. As soon as the paratroopers began floating to earth, Roach released his prisoners from their cells and told them that if they fought their offenses would merit a pardon. The prisoners gleefully accepted the firearms they were given, and Roach told his motley crew, “Let’s go headhunting for bloody Huns.” The convicts headed out, adding to their arms stores by looting German supply canisters that fell from the sky.

The defense at Modhion was not just convicts, though. The 21st and 23rd Battalions were in the area, and they were joined by Cretan civilians, angry at being invaded and armed with ancient flintlocks and fowling pieces. Four Germans racing toward their supply canister were cut down by a volley of fire from old men. The four paratroopers were killed by ancient flintlocks captured from the Turks a half century earlier. Of the total complement of 10th Company, more than 60 percent were killed or wounded at Modhion.

Scherber’s other company, the 9th, did not do well either. It landed smack over the 23rd Battalion. Scherber himself landed near a huge open-sided tent, and just as he hit the ground was gunned down, his parachute falling like a burial shroud around him. The 23rd Battalion’s commander, Lt. Col. D.F. Leckie, stood in the open, issuing orders and firing away with his pistol. With five shots, he killed five paratroopers.

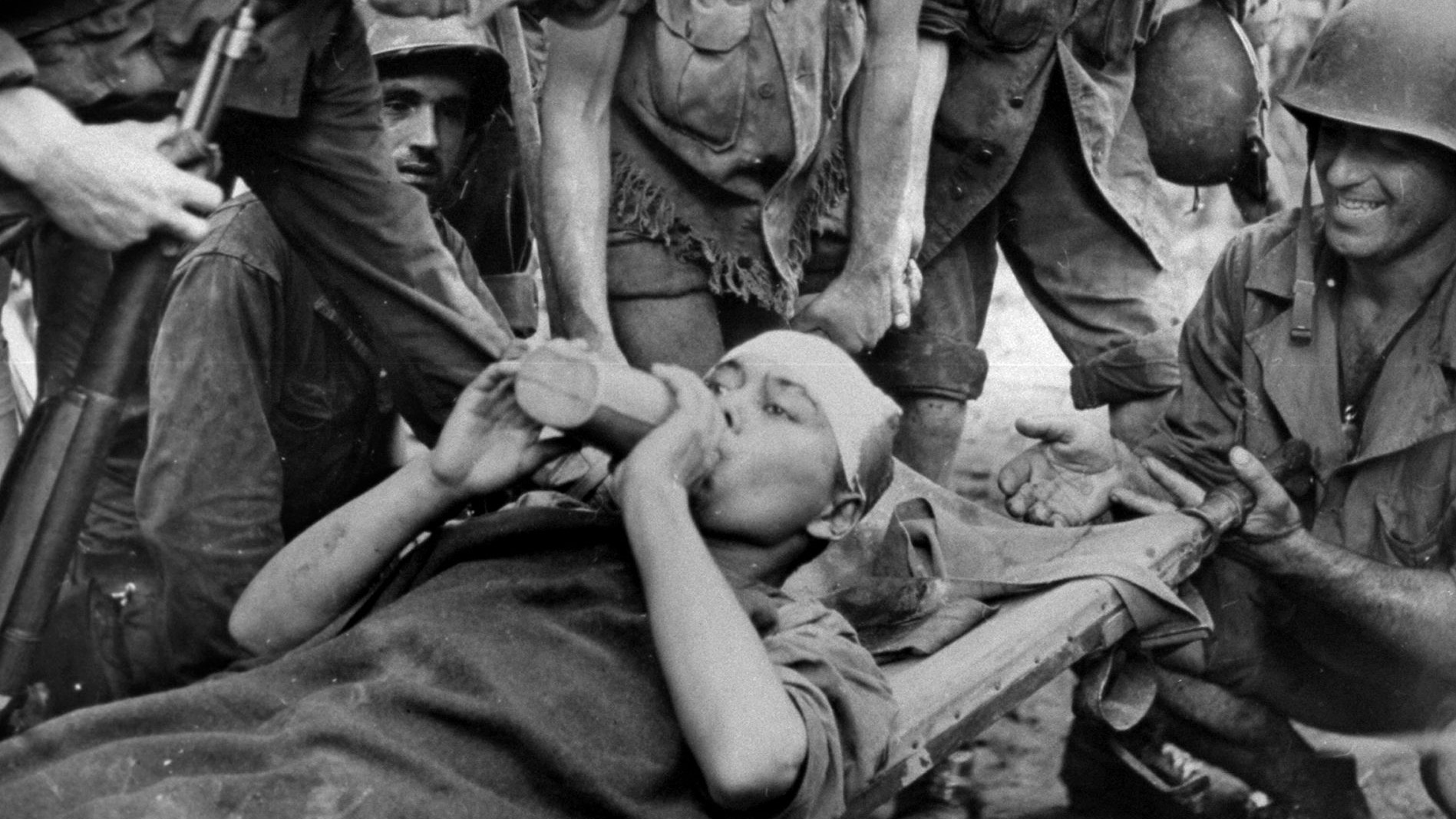

Of the 600 men in Scherber’s battalion, some 400 were killed or wounded in the first hour of battle. Of 126 men from one company of this battalion, which landed between Cretan defenders on one hill and New Zealanders on the other, just 14 survived. A survivor said of the battle, “It was like a terrible dream.”

Meanwhile, 22nd Battalion fought on. Captain Campbell’s D Company had about 70 men with no mortars and only a few machine guns. The most northerly unit in the company, 18 Platoon, down to 22 men, was thin on the ground. When the German parachutes opened, Sergeant Sargeson observed to Corporal Bob Boyd, a King County van driver in peacetime, “Look at that, Bob, you’ll never see another sight like that as long as you live.” Boyd replied, “Yes, and if we don’t shoot a few of them, we won’t live too bloody long.”

Seventeen Platoon’s Single Casualty

The soldiers of 18 Platoon fought with the experience of men who had served in the retreat in Greece and the toughness of New Zealand farmers. The men of 17 Platoon watched 17 gliders land on the dry riverbed of the Tavronitis, one on the hillside right by their positions. Corporal H.A. Kettle, a Waitara baker, remembered, “My section was issued with a Bren gun a few days before the blitz, with instructions not to fire indiscriminately with it as it was necessary to conserve ammo. We discovered upon attempting our first burst at the enemy that the gun was without a firing pin.”

Disheartened but not defeated, the men scrounged some captured German equipment, including a machine gun, and used that until ammunition ran out at 12:30 pm. Seventeen Platoon took only one casualty in the initial stages of the battle.

On D Company’s left flank, 16 Platoon held positions on the hillside overlooking the dry riverbed. Platoon leader Sergeant Vince Freeman led his men in shooting at the landing gliders.

And so it went through the battalion—gliders landing, troops firing back with everything they had, amid the roar of bombs and gunfire. The only plan was to hold the ground.

A Company held its fire until the parachutists were 100 feet from the ground, then opened up. Some 22 Germans who landed alive in A Company’s area were accounted for. During the lulls, the New Zealanders broke open the German supply canisters, finding them packed with gear, food, motorcycles, Benzedrine tablets, and even warm coffee. Captain S. Hanton, who commanded A Company, wrote, “The detailed organization of the force amazed us at the time; we had not realized that so much care could be taken to win a battle.”

The POWs’ Dash For Safety

Determined German troops cleared out the RAF camp, which was loosely defended by poorly armed and ill-trained ground crews, and then started advancing on Hill 107. In the RAF camp, the Germans found an RAF codebook and the complete British order of battle for Crete.

German paratroopers, charging through the RAF camp, shot anyone they saw but paused to line up eight RAF men they found on the surface. Leading Aircraftman Lawrence shouted that the Germans had no right to shoot POWs without the express order of an officer. The German paratroopers were amazed at the idea of POWs refusing to be shot unless an officer was sent for, and they did. The officer showed sense—he called off the shooting. But the POWs were not safe. The captors forced them to march forward as a screen to Hill 107. As they advanced, New Zealanders counterattacked from the flank. The eight RAF men took advantage of the confusion to make a dash for safety.

Other fitters and officers had already pulled back from the RAF camp and joined the New Zealanders to fight as infantrymen.

At his command post, Meindl tried to make sense out of the appalling situation. The Third Battalion had been nearly wiped out. The New Zealanders still held the airfield and Hill 107. There had been no communication with the division commander, Maj. Gen. Wilhelm Suessman, since his glider took off. It had crashed, killing all aboard. There had also been no communication with headquarters in Athens, where General Student and his command team had taken over the Hotel Grand Bretagne.

Meindl did not know it, but the entire German effort on Crete was coming apart. The forces assigned to take the airfields at Heraklion and Retimo had been stopped in their tracks. The force assigned to take Canea was trapped in a valley. The only hope the Germans had to gain control of Crete lay in the hands of the Assault Regiment at Maleme. And Meindl had lost half his men already.

A Complex Plan vs a Simple Plan

Despite their massive losses, the Germans had several advantages. Air superiority meant they could move freely without fear of air attack, and they had plenty of working wireless sets for local communications. Once the initial dislocation of landing was overcome, the Germans massed their men and proceeded in accordance with their complex plan.

The New Zealanders had a simpler plan: hold the ground. Colonel Andrew considered the morning blitz worse than a World War I barrage, and said, “I do not wish to experience another one like it.” Wounded slightly in the temple, he pulled the shell splinter out of his head. “It was bloody hot and I bled a bit.” Then he snarled, “We’ll go out and get them when the bombing stops.”

The problem for Andrew was communications. His phone lines were down, and all he had was a gradually dying radio that connected him with brigade. He was supposed to fire rockets and Verey lights to let the nearby 21st and 23rd Battalions know they had to come to his assistance, but he did not know what the situation was.

The Germans kept building up from the Tavronitis River, and Andrew wondered where and how his men were doing their jobs. Under the heavy bombing, runners could not get through to his scattered companies. Nor did Andrew have any idea of the exact German numbers facing him.

The platoon nearest the sea managed to repel attacks along the beach from the mouth of the Tavronitis. But 15 Platoon, defending the western end of the airfield, was hard pressed. Only 22 strong and lacking machine guns, they held their one-kilometer front with great tenacity.

A Sharp Attack on the Airfield and Hill 107

Meanwhile, Meindl fell back on the favorite German tactic—a sharp, sudden, violent attack. He ordered his two remaining battalion commanders to attack the airfield and Hill 107. Fourth Battalion, under Captain Walter Gericke, who took over from the late Major Braun, would charge across the captured Tavronitis Bridge and attack Hill 107 from the north. Gericke’s battalion had mostly heavy machine guns and mortar squads, which gave it firepower but few infantrymen. It would be reinforced by a company of paratroopers from 2nd Battalion and the survivors of the glider force. Gericke had quite a future in front of him. He ultimately commanded the West German Army’s parachute division.

The two remaining companies, Major Stentzler’s Fifth and Sixth, would cross the Tavronitis, circle counterclockwise in an enveloping maneuver, and assault Hill 107 from the south, thus attacking the hill from two directions. Meindl had left for Greece with 2,500 men. Now he staked the battle on 900 paratroopers.

Stentzler’s battalion of two companies tried to attack Hill 107 from the rear and ran smack into a fortuitously placed New Zealand platoon. The Germans were exhausted and dehydrated, sweltering in their gray uniforms designed for Northern Europe, loaded down with weapons, ammunition, and emergency packs. They had already emptied their canteens.

At 10 am, a C Company runner finally reached Andrew to ask him to unleash the two camouflaged tanks from their lair. But Andrew refused. It was too early to play the trump card.

At 10:55 am, Andrew warned 5th Brigade over his erratically working wireless set that he had lost contact with C and D Companies. He signaled, “400 Paratroopers landed in the area. 100 near the airfield. 150 to the east of the airfield between Maleme and Pirgos and 150 West of the river.”

“Order the Men to Attack That Damn Hill—Take it at All Costs!

Around midday, the Germans brought into action their mortars and a light field piece they had parachuted with them. The British artillery batteries could not help because the field telephone lines between the artillery pieces and the forward observation post at Hill 107 had been cut. The gunner officers instead took command of RAF and Fleet Air Arm personnel fighting as infantry.

Then Meindl gave the signal, and his two battalions attacked. At first there was the snap of sporadic fire, but when the Germans were exposed the firing became a thunderous roar. Caught in the open, the front ranks were shot dead. Others were wounded and, lying where they fell, took more bullets. The Germans retreated. Meindl ordered the assault to continue.

But then Meindl saw one of Koch’s men hoisting a flag signal halfway up Hill 107. They had reached the point after fierce fighting but could not advance any farther. Meindl grabbed a green signal flag lying on the ground and raised himself over a stone wall to wag back an answer, astonishing his staff since this was a signalman’s job, not the commander’s.

As he stood signaling, Meindl was hit in the hand by a sniper’s bullet. He grabbed at his wrist, fell, rose again, and took another bullet in his chest, then slumped to the ground. The wounds were not fatal. As the medics dressed them, Meindl barked at his men, “Order the men to attack that damn hill—take it at all costs! Don’t come back until it is in your hands!”

A Lack of Support from Hargest

The Fourth Battalion followed orders. They reformed and stormed up the hill, leaping over the bodies of their buddies, firing their rifles until they were empty, then turning to their bayonets. But the New Zealanders would not budge. The 22nd took heavy casualties but held its ground.

At the bottom, the pale Meindl was told that Stenzler’s Second Battalion had been held up by lack of water, and runners were out searching for canteens for the parched men. Meindl ordered the attack to resume without delay.

On the high ground, the New Zealanders were having their own hard time. They were just as tired and parched as their German counterparts but were hanging on.

Andrew regarded his situation as serious and fired up white and green flares, the emergency signal to 23rd Battalion for help, but nobody saw them in the smoke and haze.

Incredibly, 5th Brigade made little effort to contact him, satisfying itself with messages from the 21st and 23rd Battalions that the area was under control. Hargest signaled back to the two battalions: “Glad of your message … will not call on you for counterattack unless position is very serious. So far everything is in hand and reports from other units satisfactory.” So while Andrew fired off flares and radio messages to his superiors, they did not move or answer.

At 3:50 pm, Andrew finally got a radio message through to Hargest’s headquarters just 6.5 kilometers away but got no reaction. With mortar shells landing around his command post and no response from his higher-ups, Andrew was running out of ideas.

Hargest’s behavior is difficult to explain, and historians have tried. Unlike Andrew, he was not a professional soldier, but a plump, red-faced farmer and Conservative member of the New Zealand House of Representatives. Pehaps he was exhausted from the violent strain of battle. His communications may have been disrupted. He may have been more concerned about the seaborne invasion. Whatever the cause, Hargest did not send any help to the 22nd Battalion.

Advance of the Matilda Tanks

Andrew was down to his trump card, the two Matilda tanks. He ordered them along with his reserve 14th Platoon of 19 men under Lieutenant H.T. Donald and six gunner volunteers from 156th Light Antiaircraft Battery into action to clear out the German troops holding a portion of the airfield.

Sergeant Dick Fahey, who commanded one of the tanks, leaped out of his foxhole and with his buddies started removing camouflage from the two vehicles. Down came broken olive branches, uprooted cacti, and hunks of sod covering a huge camouflage net. Fahey revved up his tank’s motors.

The tanks emerged like dinosaurs from their camouflaged lair and rumbled toward the Germans in the wrong place. They headed for the Tavronitis riverbed about 30 yards apart.

The tanks clattered into the advance, German small-arms fire ricocheting off the Matildas’ tough hulls. The sound of bullets made Fahey’s ears ring. He saw a group of Germans to his right and ordered his gunner to sight on the target and open fire.

No response.

“What the hell are you waiting for?” Fahey shouted. “Load it!”

The gunner answered, “The shell won’t fit—it’s too big!” Fahey stepped over to the gunner’s position and found he was right. All the shells in the tank’s ammunition rack were for a larger caliber gun. Fahey was livid. “What the bloody hell! Here we are leading an attack and we can’t even spit at them!”

“If You Must, Then You Must”

Deciding that they could at least overrun the enemy with their treads, they rumbled toward the bridge, then bumped and lurched down into the riverbed. The tank tried to attack the Germans on the flank, passing unscathed through German small-arms fire, but the armored belly struck a boulder and the tank was now a stranded turtle, its treads chewing deeper and deeper into mud. Inside, Fahey and his crew found they could not traverse their turret and abandoned the vehicle.

The second tank could not traverse its turret, so it had to withdraw.

The accompanying infantry was now unprotected and came under heavy German fire. The lead section was killed, as were all the Bofors gunners. The rest—eight survivors of 26—withdrew to Andrew’s command post.

As he watched the dispirited eight men walk past him, suddenly Andrew lost faith in his ability to hold Hill 107. Convinced that two of his companies were lost, his mortars and machine guns gone, his position untenable, he put through a radio message begging again for reinforcements, saying that if he did not get them he would have to withdraw from the high ground.

This time, Andrew got an answer. “If you must, then you must,” Hargest radioed back. But he would send help. Andrew was now stuck.

Andrew was no coward—he held a Victoria Cross. He was also no fool. But he was exhausted from an extremely difficult day, disconnected from two of his companies, and surrounded by German paratroopers. It was a desperate situation. As Dan Davin observed in his official history, Andrew’s “decision to withdraw was taken by an experienced soldier and a brave man who had won a Victoria Cross in World War I. No one who has not shared ordeals and anxieties comparable with those he had endured this day can comfortably criticize him, but the fact remains that by withdrawing from Point 107 and the airfield he gave the enemy the only chance of exploiting the lodgment they had gained.”

Freyberg was less harsh in a 1956 letter to 22nd Battalion’s official historian, Jim Henderson, writing, “Let me say at once, I do not for one moment hold Col. Andrew responsible for the failure to hold Maleme; he was given an impossible task, and he has my sympathy. I take full responsibility as regards the policy of holding the aerodrome. I did not like the defenses of any of my four garrisons. I would have put in another Infantry Battalion to help Andrew, but it was impossible in the time to dig them in. The ground was solid rock, neither did we have the tools. [Acting Division Commander] Puttick, Hargest and I must bear our share of responsibility for the defensive positions that were taken up at Maleme, which were as good as we could hope for under the difficult circumstances.”

Andrew sent his runners to communicate the bad news to C and D Companies, which were battered but intact—but the runners did not get through. C and D Companies did not get the word. They were waiting for relief.

Reinforcements at Night

Another high officer was worrying about the situation in Crete. General Student had received nothing but bad news since the attack had begun. Worse, Student’s rivals in Berlin were urging Hitler to end the operation and withdraw the troops. Naturally, there was no way to do this, not while the Royal Navy dominated the sealanes, especially by night. Student’s career and the lives of 10,000 paratroopers were at stake.

Then Student had a better idea. There was still a chance at Maleme, where his troops were putting up a fight. And Student still had his Force Reserve—two battalions of paratroopers ready to jump—that could be dropped at Maleme to provide the attackers with a little more punch. With one more good shove, Maleme could be German, and the mountain troops could start flying in. The whole battle, he decided, would focus on Maleme. But he needed accurate information from the battlefield.

Student ordered Captain Kleye, one of his staff officers, to fly to Maleme with a working radio, and report on the situation. Within an hour, Kleye was in a Ju-52 headed for Maleme. Incredibly, in total darkness the lumbering Ju-52 put Kleye down on the western edge of the airfield. The plane dropped him and the radio, revved up to its full 830 horsepower, and took back off for Athens. An hour later, Kleye reported to Student that Maleme Airfield was usable and that the paratroopers there could attack again if resupplied.

An emboldened Student began to issue orders. Supplies would be sent in. The force reserve under Colonel Bernhard Ramcke would parachute to Meindl’s rescue. And the 100th Mountain Regiment would be put on standby to fly in to Maleme Airfield, to take off at dawn. The division’s boss, Maj. Gen. Julius Ringel, a goateed Austrian Nazi, would take overall command, putting a fresh leader at the helm of the flagging attack.

As the sun set over Crete, the fighting died down at Hill 107. The Germans were scattered, alone or in small groups. They were thirsty, hungry, tense, and exhausted. The New Zealanders, up on the Hill, were the same. Meindl, weary with his wounds, worried about a counterattack. “What are the English waiting for?” he asked his aide over and over again in a pain-filled voice. He had less than 50 paratroopers holding the lower part of the western slope of Hill 107.

The New Zealand defenders were also reviewing the situation. Hargest had decided to send reinforcements to Andrew. He ordered Colonel Leckie of the 23rd Battalion to dispatch one company of infantry to assist Andrew on Hill 107 and another from the 28th Maori Battalion in reserve.

Andrew was baffled by the decision. Why send two companies from two separate battalions? Why not send two companies from the same battalion? Why only two companies at all? Moving men around in the dark in battle was not an easy affair.

As the night wore on, the reinforcements did not arrive. By 9 pm, they had not shown, and Andrew ordered the men of Company A to pull off the high ground of Hill 107 and descend to a lower point held by Company B. Half an hour later, the reinforcing company from the 23rd arrived under Captain C.N. Watson. Andrew sent them up to hold the old A Company position.

Incredibly, while Hargest made all these decisions he did not pass them up his chain of command to the acting divisional commander, Brigadier Edward Puttick. All day he reported that things were going well at Maleme. Suddenly, at 11:15 pm he asked Puttick’s permission to send the entire 28th Battalion to Maleme. For the first time all day, the top brass realized things were going badly at Maleme.

“You Are Damned Lucky to Be Alive”

A little after midnight, the 22nd Battalion commander ordered his A and B Companies to leave their positions on the lower slopes of Hill 107. Captain Watson’s relief company would act as rear guard during the withdrawal.

At 1:30 am, the Maori company from the 28th, under Captain Rangi Royal, finally arrived, having taken six hours to get there from Platanias. En route, they had stumbled into German paratroopers and fought several skirmishes. Royal’s men had to make a bayonet charge to break through. When they reached Andrew’s position, Andrew said dejectedly, “You are too late, Captain. The situation has deteriorated to the point that I have to pull out.”

Royal reported his bayonet charge, and Andrew said, “You are damned lucky to be alive.”

Andrew still had an opportunity to save the day. He had 300 unwounded men available to defend the hill, and 150 men from 23rd Battalion, plus 100 or so more from the 28th. That gave Andrew 630 men to hold Hill 107, almost as many as he had at the start of the battle. Instead of leading the new men and old men back up the hill to hold the high ground, Andrew followed the opposite course.

“It is too late, Captain Royal,” Andrew said adamantly. “It’s too late. I suggest you take all your men back to Platanias.”

The Silent Withdrawal From Hill 107

At 2 am, Captain Watson and his relief company also left Hill 107 and followed Andrew’s men back to the 23rd Battalion. Minutes later, two runners from Captain Beavens’s isolated Headquarters Company at Pirgos finally burst through to the Command Post of 22nd Battalion to find it empty. It was then too late to let Andrew know that his missing companies were relatively intact. Beavens himself undertook a personal reconnaissance of B Company’s positions only to find them abandoned. He decided to withdraw at 3 am.

What happened to the other companies of 22nd Battalion? C Company spent the whole day making fruitless counterattacks, withering away. At 4:20 am, the battered company also withdrew, yielding most of the airfield to the Germans. C Company sheltered in trees to avoid the morning bombing, then pulled back to 21st Battalion’s area.

D Company got the word from a straggler, a Royal Marine gunner, who told D Company’s Captain Campbell that the rest of the battalion had withdrawn. Campbell refused to believe it. Thirst was his main problem. He and his company sergeant major set off to battalion headquarters to get water and the word. They were shocked to find the battalion had indeed gone.

To ensure silence, the New Zealanders took off their boots and hung them around their necks. They were silent anyway—they knew they had absorbed severe punishment and had held the high ground all day. They wanted to stay and fight it out. Most of all, they resented leaving so many comrades behind. As the men retreated, they heard the sound of snoring Germans around them. An irritated New Zealander silenced some of the snoring by hurling a hand grenade into the darkness. The snoring was replaced with screaming and bursts of machine-gun fire. The New Zealanders trotted away down the hill.

One in Four Paratroopers Killed

With Maleme’s fall, the Battle of Crete was lost. It had nine bloody days left to run, but the rest was a long delaying action to enable the British and Commonwealth forces to evacuate their men from the island. With Maleme Airfield secured by the Germans, they began landing green-clad mountain troops, whose numbers and firepower would overwhelm the British defenders.

Ironically, the victory was a phyrric one for Germany. One of every four paratroopers who made the jump on Crete died on the rugged island, and Hitler was so shocked by the losses that he forbade any further large-scale parachute operations. German paratroopers would spend the rest of the war fighting as elite infantry, specializing in counterattacks and last-ditch stands, but never again make a mass jump. Crete itself would not become the gateway for German airborne or seaborne advance. The island instead became a backwater of the war, occupied by German troops who spent much time battling guerrillas.

The 22nd Battalion and Colonel Andrew survived their ordeal depleted but unbowed to fight other battles in North Africa and Italy, ultimately driving all the way through Italy to Trieste.

Early on May 21, the Germans opened fire with machine guns on the New Zealanders and were surprised to find no answer from Hill 107. The senior paratrooper, Dr. Heinrich Neumann, the Assault Regiment’s physician, led a small group of men up the western slope of Hill 107 to the summit. German propaganda would make it appear that Neumann, a notorious disciplinarian in steel-rimmed spectacles, took the hill with a heroic assault. In fact, there were just a few shots in the dark.

There, he was met by 1st Lieutenant Horst Trebes, who led a platoon from Stentzler’s Second Battalion, which had approached the crest from the southern slope. Incredibly, Hill 107 was abandoned and empty.

As the sun rose over Crete and Greece, the German Ju-52s lined up on airfields around Athens and began delivering the 100th Mountain Regiment to Crete. They would come under artillery and flak fire as they approached Maleme, which disrupted landings, but ultimately, the Austrian mountaineers would start unloading their gear and head east to take on the New Zealand defenders and conquer the island.

On May the h 1941, ANZAC, Greek and British forces stood side by side with the heroic population of Crete in the defense of their Southern Mediterranean Island against the elite of Hitler s war machine. The ensuing battle is etched forever in ANZAC history. Now, 80 years later, veterans and the descendants of these brave soldiers, will join with the local Cretan population to honour their courageous endeavours. Join us in May 2021 and attend the commemorative services, explore the battlefields and share the stories.

On May the h 1941, ANZAC, Greek and British forces stood side by side with the heroic population of Crete in the defense of their Southern Mediterranean Island against the elite of Hitler s war machine. The ensuing battle is etched forever in ANZAC history. Now, 80 years later, veterans and the descendants of these brave soldiers, will join with the local Cretan population to honour their courageous endeavours. Join us in May 2021 and attend the commemorative services, explore the battlefields and share the stories.