by Kevin Hymel

A German SS officer, holding a white flag of truce, walked through the American lines and up to a tall lieutenant from Texas. Surrounded for three days, the Americans were outnumbered four to one with little hope of relief. “Your situation is hopeless,” explained the German, adding that if the Americans did not surrender, they would be “blown to bits.” Around them lay wounded Americans, many suffering with gangrene. Other soldiers—dirty, hungry, and thirsty—hunkered down in foxholes or behind boulders. Smoking hulks of tanks littered the battlefield; blackened craters and bare tree trunks covered the ground. The American lieutenant weighed the offer for a second before delivering a curt response: “Go **** yourself.”

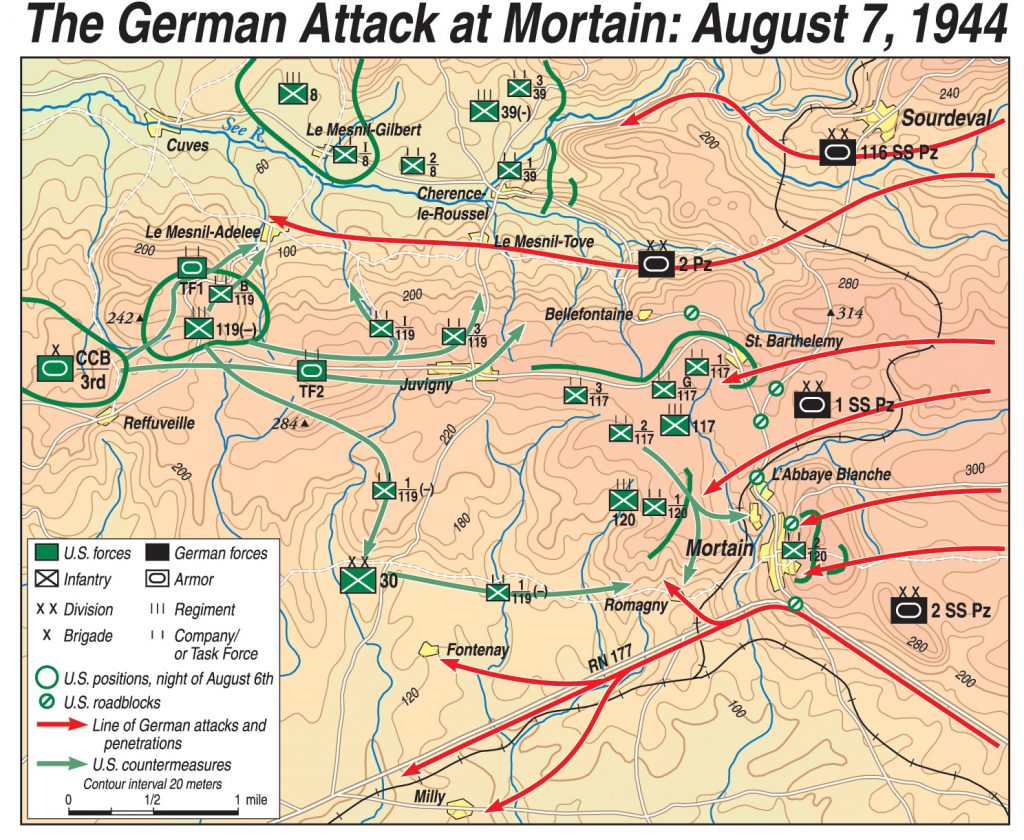

In the first week of August 1944, the Germans were on the attack in Normandy. After being pushed off the D-Day beaches by Lt. Gen. Omar Bradley’s First Army and suffering a rupture in their lines by Lt. Gen. George S. Patton Jr.’s Third Army, the Germans launched a counteroffensive of four Panzer divisions to smash the American lines and capture the vital French coastal town of Avranches, where Patton’s tanks poured into the Continent.

An hour after midnight on August 7, 1944, more than 50,000 German troops and 300 tanks advanced westward. The 2nd SS Panzer Division targeted Mortain, a small town 20 miles directly east of Avranches. In the way of this armored assault stood the 30th Infantry Division, an American National Guard unit that landed a month earlier in Normandy. Called the Old Hickory Division in honor of President Andrew Jackson, the 30th had just replaced the 1st Infantry Division at Mortain a day earlier and barely had time to dig in before the Germans struck.

Monday, August 7 (Day 1)

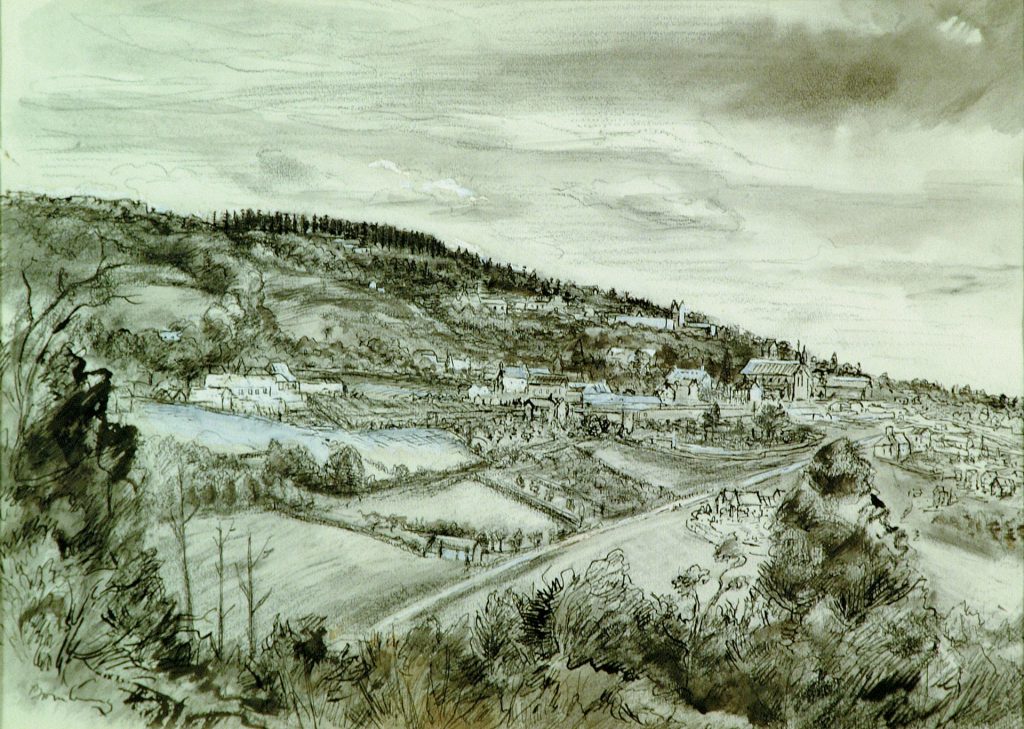

A predawn German attack splintered the Old Hickory, overrunning roadblocks and capturing and killing scores of Americans. But islands of resistance denied the Germans key locations. The most important was Hill 314, overlooking Mortain from the east, which towered over the terrain for miles. The hill was ideal for defense, with huge boulders and dense undergrowth. The north and east sides of the hill sloped gently and were road accessible, but the south and west sides formed sheer cliffs above the town. On a clear day, Hill 314 provided a panorama of the French countryside for more than 30 miles.

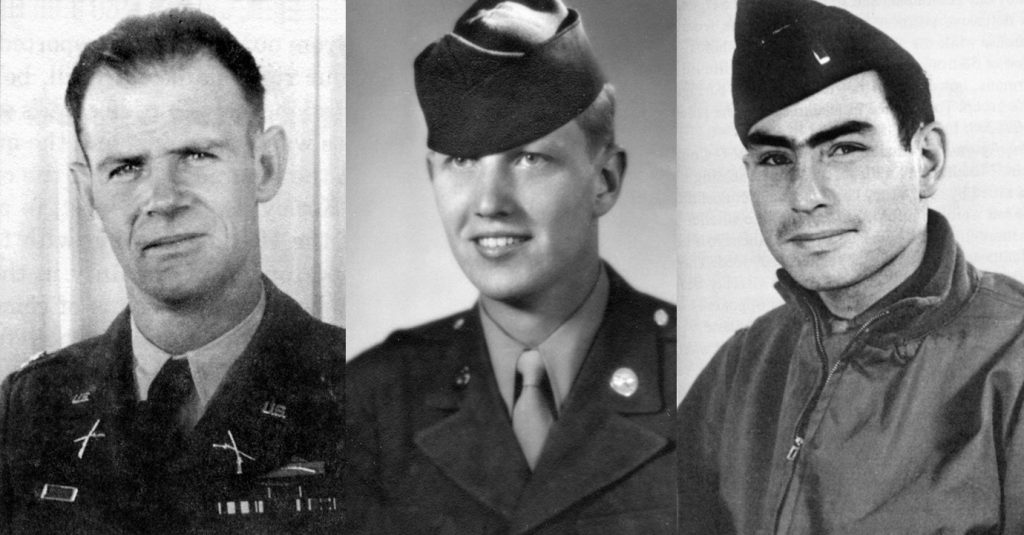

Lieutenant Colonel Eads Hardaway, the commander of the division’s 2nd Battalion, 120th Infantry Regiment, set up his headquarters in Mortain and sent his E, G, and K Companies to the crest of the Hill 314, placing them in a triangular perimeter. Lieutenant Joseph Reaser’s K Company covered the north; Lieutenant Ronald Woody’s G Company covered the southwest; and Lieutenant Ralph Kerley’s E Company covered the southeast. The 2nd Battalion’s GIs had only bazookas and mortars, but they possessed two artillery forward observer teams, both from the 230th Field Artillery Battalion. Lieutenant Robert Weiss commanded one team (Battery B), Lieutenant Charles Bartz the other (Battery C).

Both teams spent the previous day plotting artillery support. “I would plot out emergency barrage numbers and normal barrage numbers,” explained Sergeant Frank Denius, from Bartz’s team. Emergency barrage numbers were pinpointed on expected counterattack areas. During an attack, an observer only had to request “Emergency Barrage Number 1” and the gunners would know where to fire. Normal barrage numbers disrupted suspected supplies and support areas farther back. “If you got attacked at night, [artillery] had to come immediately,” explained Denius. “My battalion had 12 105s, but in an emergency we could have all division artillery, then we had artillery from other divisions and corps artillery.”

The clanking tank treads warned the men atop Hill 314 of the impending attack. The Germans struck around 1 am and quickly overran a roadblock on the southeastern edge of the hill. Survivors straggled into the perimeter. The Germans pressed their attack, cutting off communications between the hill and Lieutenant Colonel Hardaway’s battalion headquarters in Mortain. Enemy tanks and infantry rushed up the eastern and southeastern slopes, the soldiers shouting, “Heil Hitler!” and charged G Company’s foxholes near a small church called La Petite Chapelle.

As German tanks and infantry slammed into G Company, Lieutenant Kerley ordered Lieutenant Weiss to call in artillery fire. Blinded by darkness and fog, Weiss could hear the approaching tanks and radioed coordinates to the artillery based on his best guess. Shells rained down on the Germans. In a short, sharp skirmish, the American brushed them off the heights.

Lieutenant Bartz’s observation team was stuck in the front lines, unable to call in rounds lest they reveal their position to the Germans. The attack took Bartz out of the fight, but the rest of his team, Sergeant Frank Denius and Technical Sergeant Sherman Goldstein, made it back to Kerley’s headquarters. By the time they set up their radio and began adding to Weiss’s artillery requests, two hours had passed. Denius and Goldstein would work well together for the duration of the battle. “I was an instrument operator,” recalled Denius. “Sherman Goldstein was the radio sergeant. When I called out directions for fire, he relayed them to battalion.”

Once the GIs halted the attack, Lieutenant Kerley did something odd. He removed his helmet, lay down on the ground. and fell asleep. The panicked men around him suddenly calmed. Dense fog held the battlefield in check. He finally awoke an hour later, refreshed. He led the rest of the battle energetically and with a clear head. It would be his last bit of sleep for the next week.

Kerley was amazed at what he saw once the sun burned off the fog: “Columns of enemy armor and foot troops streaming [toward us] from the east and northeast.” The Germans were packed together, an easy target. Weiss and Denius called fire missions, and shells began exploding among the attackers, killing and maiming scores of Germans, destroying tanks and vehicles, and sending survivors scurrying down the hill.

While Weiss called in artillery on the east and northeast, Denius called for fire on the south and southwest. “I saw German infantry and tanks attacking,” said Denius. “It was the first time that we had seen that many tanks and that large a concentration attacking us.” Denius eyed a large intersection on the southeast corner below Hill 314, where the Germans were trying to either bypass the hill or attack it from behind. He and Goldstein ordered fire on the intersection and continued to do so during the course of the battle.

The Germans retaliated with 88mm artillery fire. Several rounds exploded near Weiss, but the angle of fire and the huge boulders offered refuge. The shrapnel merely nipped the top of his radio antenna. Others were not as lucky. An 88 explosion knocked down a Native American soldier running up the hill. He lay there, shaking with fright before gathering the courage to stand, put his helmet on, and continued up the slope. While Weiss remained with Kerley, Denius and Goldstein moved between the three companies, offering fire support where they could.

The Germans continued to probe the hill, but Companies E and K pushed them back. It was no easy task. When an enemy sniper began shooting at E Company, Lieutenant Kerley asked one of his men for his rifle and then disappeared for about 20 minutes. His men worried about him until they heard two shots ring out. Kerley emerged from the scrub and quietly offered the man his rifle back. “Thanks son,” was all he said.

One German assault managed to capture several K Company rifle squads. Elsewhere, an E Company soldier, Private Paul Nethery, exchanged fire with a group of Germans. He was hit in the head and leg, but Nethery wounded an SS officer, who was then captured. The German turned out to be an artillery spotter, an important catch for the Americans.

As the morning wore on, men from the town below began drifting into Hill 314’s perimeter. One unit arrived intact. Captain Reynold Erichson from F Company led a 40-man platoon from C Company onto the hilltop. Erichson had left the hilltop for battalion headquarters when communications died. Once there, Lt. Col. Hardaway gave Erichson the platoon and ordered him back up the hill.

Erichson spent most of the day trying to find a way back into the perimeter. He and his men constantly stumbled into groups of SS soldiers who forced Erichson to change directions. In the final dash, a German half-track with a mounted machine gun opened up on Erichson’s men. Fortunately, the G Company soldiers atop Hill 314 dropped mortars on the Germans, enabling the trapped men to disengage and wriggle up the hill on their bellies. One of the last to make it into the perimeter was Captain Delmont Byrn of H Company, who was taken aback at what he found. “I was kind of shocked to see injured men lying there in the open, being hit again by shrapnel.”

Above, American Ninth Air Force fighter planes flew 429 sorties to keep the Luftwaffe out of the skies that first day. Ten squadrons of Hawker Typhoons of the British Second Tactical Air Force flew 290 sorties and fired 2,088 rocket s at German tanks and vehicles below, keeping the enemy at bay. “I’ll never forget the sound of those rockets fired from the British Typhoons,” explained Denius. “We had never heard anything like that before.”

With most of Mortain in German hands, Lt. Col. Hardaway radioed Captain Erichson that he was now the temporary commander of the three companies. As the sun went down, Erichson ordered a survey of the remaining ammunition supplies. Each company reported severe shortages or depots inaccessible because of German snipers. At least 78 GIs were killed, wounded, or captured. There was no relief in sight.

Tuesday, August 8 (Day 2)

During the night, Lieutenant Woody shifted G Company’s position closer to Lieutenant Reaser’s K Company and away from Le Petit Chapelle, consolidating the perimeter but isolating Lieutenant Kerley’s E Company. Throughout the night and into the next morning the artillery observers called in heavy fire every time the Germans massed for an attack. Whenever the Germans fired an artillery shell or a tank round, the observers quickly pinpointed the location and rained fire.

Finally, a lone Panther tank plowed through a hail of fire and roared onto the hilltop. The men held silent as the tank drove through the perimeter. An American bazooka team tried to get into a firing position while Denius raced to the area to call artillery rounds on the tank. Finally, the Panther’s commander, probably realizing he was alone, turned around without firing a shot and retreated down the hill.

Although the lone tank was the only real attack of the day, the Americans had other worries. With no resupply, men were running low on food. They had pooled their K-rations, reserving some for the wounded, but soon ran out. Some dug potatoes and cabbages from an abandoned farm or plucked apples from an orchard. “That first bite of cabbage was about the most delicious taste I ever experienced,” said Private Thomas Street. One soldier donated his bottle of cognac to fuel a fire used to cook potato soup.

Private First Class Allen Newhouse later recalled, “It was the first time I ever ate green apples without getting a stomach ache.” Sergeant Denius relied on his chocolate D-Bar, shaving portions for himself with his bayonet. “I was neither hungry nor thirsty,” recalled Denius, who was too busy calling in fire to think about food.

Some of the men found a cistern filled with “fairly greenish” water. They filled their canteens and dropped in purifying pills, “but it didn’t help the taste,” said Private Street. German snipers kept a freshwater well on the edge of the American perimeter under fire. A few thirsty soldiers said, “To hell with enemy snipers!” and crawled to it. One man provided covering fire while the other filled canteens.

With no medical equipment, casualties mounted. Even though the healthy men donated their first aid packs to the medics, medical supplies were being used up. “We were watching men die because we had no disinfectant, no bandages, except what was in the tiny first-aid kits we carried,” said Captain Byrn.

And then there were the radio batteries, the crucial weapons that kept the artillery observers in business and the enemy at bay. The artillery observers used their radios sparingly. They found that turning off their radios for a couple of hours recharged the batteries a little, adding about five to 10 minutes of life. They also placed spare batteries on rocks in the sun, hoping the heat would recharge them. “I didn’t know if putting them in the sun worked,” said Denius, “but we tried it.”

In an effort to resupply the men, two light artillery spotter planes packed with food swooped down on the hill. But the planes came under withering German fire and were forced to turn back before dropping their loads. The men on Hill 314 would have to wait.

Up on the hill, Captain Byrne worked to consolidate the American perimeter. He braved mortar and small arms fire to link up with Companies G and K. “As I had not learned to be scared yet, I made a fairly good example,” he remembered.

By 2 pm, the Germans attacked G Company, this time from the west, from the town of Mortain. White phosphorous shells dropped on the hill, burning some of the Americans. Lieutenant Weiss quickly found cover and escaped the burning particles. He then called a fire mission on a group of enemy howitzers. Company G repulsed the attack, breaking up German concentrations with mortars. “Every time we saw the Germans forming up for an attack, we’d drop a few shells on top of them,” recalled one soldier. But the Americans absorbed more casualties in the process.

Denius also called in artillery. “You could see the attack coming,” he explained. “I would just put as much artillery into the area as I could. German tanks were very quiet and could slip up on you.”

As the sun set, men gathered the dead and placed them out of sight, lest their presence reduce morale. The Germans tried another night attack, but American artillery kept them at bay. Weiss called in fire on the supply routes he had already zeroed in. He then directed artillery against three attacks by the Germans. Denius ordered fire on the southern intersection intermittently, staggering the rounds with two-minute breaks, then eight minutes, then another pause before firing again. “We asked them to keep firing, to do interdiction fire on 24/7.”

Wednesday, August 9 (Day 3)

Early on Wednesday, the Germans launched an armored attack from the east against E Company’s roadblock, trying to split the American perimeter. Artillery repulsed the first line of tanks, and the same steel curtain greeted the infantry. Then three light tanks attacked, followed by bicycle troops. The Germans attacked four times in one hour with more attacks to come. More and more tanks and infantry kept assaulting the same area, trying to break through, only to be halted by a rain of shells.

Having no success, the Germans gathered at the southwest corner of the hill and charged near the La Petite Chapelle. Tossing phosphorous grenades, they pushed forward. Some shouted, “Kamerad!” and waved white flags, then pulled out guns and started shooting. Lieutenant Weiss withheld fire, worried that he might call it on his own men. A German grenade exploded beneath an American .30-caliber machine gun. One of the men was wounded, but Sergeant Luther Myers survived the blast and field stripped the weapon in the dark to get it working again. One of the riflemen in front of Myers was hit in the arm and began crawling back toward him. Myers repaired the machine gun just in time to cover the man. Then he opened fire on the Germans, stopping their attack cold.

When firing ceased, men called for medics, who showed up with empty medical satchels. Unable to help their comrades, they went back to their foxholes. Shortly thereafter, a German officer began collecting rifles from the battlefield. Myers used his rifle to draw a bead on the German and fired. “I didn’t even have to use the machine gun,” recalled Myers about the easy kill.

Around 5:30 pm, a specially fitted American PB-38J, a fighter plane equipped with a glass nose in order to take photographs, flew over the battlefield and surveyed the terrain for the next day’s arrival of transport planes. Unfortunately, the Germans shot at the plane as it circled, and it crashed in a nearby forest.

The artillery duel intensified, with the Germans getting the worst of it. “The Germans are building up strong reserves on all sides,” Lieutenant Weiss reported to Division. “We are laying a ring of fire.” The Americans fired 30 observed counterbattery missions in an hour, a record for the European Theater. “I can’t tell you how many German trucks and tanks we knocked out,” recalled Denius. “We had great vision when we could see clear enough.”

Everything was running out. Ammunition stocks were low, medical supplies were threadbare, and the food had been consumed. To make matters worse, the dead began decomposing in the August heat. “The future looked anything but bright,” said Lieutenant Kerley, “and morale was on the decline.” Men buried their dog tags, rings, and anything of value, preparing to be overrun.

Then the German SS officer with the white flag walked up the hill and requested the Americans’ surrender. He was brought before Lieutenant Kerley, who gave his curt reply and added: “When the last round of our ammunition is fired and the last bayonet has been broken in one of your bastard bellies, then we might talk surrender. But I doubt it. Now get the hell off this hill before I shoot you off.”

The surrender request and the attack had an odd effect on the 2nd Battalion men. Their despondency disappeared, replaced by anger and resolve. “It was like nobody expected to live anymore,” explained Captain Byrn. The men now concentrated on fighting to the last, taking as many Germans with them as possible. When an officer back at headquarters learned of Kerley’s statement, he declared: “That’s telling the son-of-a-bitch.”

The Germans were good to their word. At 8:15 pm with the sun low in the western sky, a single Tiger tank blasted through the E Company roadblock and entered the perimeter. After firing a few rounds, the tank’s hatch opened and a German rose out of it. “Surrender or die!” he shouted. After a few moments of silence, an American broke cover, climbed onto the tank, and clung to the turret as the tank sped back to enemy lines.

Even though the Germans eased their pressure on August 10, the radio battery shortage was becoming acute. Radios were no longer used to communicate between companies. Instead, the platoon and company leaders used runners. “Our batteries were so weak we could hardly hear,” said Sergeant Harry Walker with K Company. “Corporal Brown [some three miles back with the artillery pieces] kept telling me to speak up; he could hardly hear me.”

That afternoon a flight of Republic P-47 Thunderbolt fighter-bombers flew over the hill, bombing German positions. The Americans took cover in their foxholes, but the pilots above knew who held the top of the hill. Four hours later the fighter planes returned, escorting C-47 transport aircraft. Their aircrews kicked out supplies, which floated down under different colored parachutes. To protect themselves from ground fire, the C-47s flew at a high altitude, resulting in most of the supplies landing behind German lines. Desperate for ammunition, food, and batteries, American raiding parties raced into No-Man’s-Land and retrieved some of the canisters. Most of the supplies consisted of ammunition and food. No batteries or medical supplies were retrieved.

Some of the supplies were ridiculous. Packed in boxes were .30-caliber rounds designed for World War I-style rifles. The men could use them in their M1 Garands, but they had to load them individually. Knowing that the Germans were listening, the radio operators bragged that they now had plenty of food, water, and ammunition.

As the sun went down, the American artillerymen shelled the hill, but with a different purpose. The artillerymen used propaganda shells, replacing leaflets with plasma, bandages, tape, and morphine. The word went out to expect artillery shells with red stripes around their bases. The artillerymen, 10 miles away, fired at the large white rocks on the northwest face of the hill. Some shells hit, bounced into the air, and imbedded themselves in the ground.

The men on Hill 314 had trouble finding these shells in the dark. They beat one shell, trying to crack it open, until someone realized it had no markings. The medical shells were only a partial success. Many were lost in the darkness. Also, the impact against the rocks destroyed the plasma. The men were able to extract bandages and penicillin, but it was not enough. “Every guy who was wounded got some penicillin,” explained Denius. “I can still see the smile on those guys’ faces when they got that medicine.”

Friday, August 11 (Day 6)

Throughout the darkness of August 11, division artillery kept a ring of fire around Hill 314, concentrating on the road nets. Dawn brought a big surprise: German vehicles heading east, away from Mortain. The Germans were retreating. Artillery opened up on the vehicles, depleting their numbers. The Germans around the base of the hill, however, showed no signs of retreating and kept up deadly sniper fire and assaults, trying to break into the American perimeter. As the morning wore on, a rumor circulated that the relief force would reach them around noon. “As the Germans fell back,” explained Denius, “we were encouraged that friendly forces were getting closer and closer.” When the hour passed with no relief in sight, the men were bitterly disappointed.

A second airdrop proved even worse than its predecessor. More artillery shells were recovered, but, once again, most of the plasma and morphine did not survive the firing. The velocity of a shell leaving the barrel simply smashed almost everything inside. A few bandages and some sulfa powder survived, and wide rolls of adhesive tape were flattened into inch-long disks.

Unable to rush the line, the Germans dropped a series of mortar shells on the American positions and then paused, waiting for the Americans to expose themselves before firing another series. The effects were horrible. The ground shook, bodies rose and fell with the impacts, and men choked on dust. Some ran to the southern edge of the perimeter, but there was no safe place to hide. To the Americans, it seemed that any movement, however slight, brought on mortars.

When the Americans spied a German team setting up a mortar, a sergeant with only a single mortar round set up his own. Once he completed his computations and adjustments, he kissed his final round, dropped it in the tube, and ducked. The round exploded about 10 yards from the enemy mortar, and the surviving Germans fled.

The 2nd Battalion had held out for six days without substantial resupply or definite signs of relief. The men had fought above and beyond the call of duty. But the strain of battle, little food, and dwindling ammunition spelled disaster. Even the bravest soldiers could not fight indefinitely without help or rest. As the sun went down that Friday night, Lieutenant Weiss signed off on his radio with a dire warning: “Without reinforcements, can hold until tomorrow.” He never received the division commander’s reply: “Reinforcements on the way. Hold out.”

Saturday, August 12 (Day 7)

The Germans withdrew from around Hill 314 in the predawn hours. A departing tank shot a random shell into the perimeter, almost severing Staff Sergeant John Corn’s right leg. He held on for a few hours while Lieutenant Weiss loosened and tightened a belt around his leg, but when Corn knew the end was near he offered his nickel-plated pistol and his watch to some nearby infantrymen. He died a few hours later.

Before noon, a column of American vehicles from the 35th Infantry Division raced up the southern side of the hill. In the van were two Sherman tanks, followed by a truck packed with food, water, and medical supplies. A single Sherman came next, followed closely by ambulances. An hour later, another regiment of Old Hickory, the 119th, pushed through Mortain and relieved the northern end of the hill.

The wounded were treated and loaded into the ambulances. The men of 2nd Battalion were then given food. “I didn’t know anything could taste so good,” said Sergeant Myers about a bouillon cube dissolved in cold water. Pfc. Leo Temkin admitted to loving his K-rations. “Funny thing,” he confessed, “They tasted good. And I didn’t like K rations.” Sergeant Denius enjoyed fresh water and was treated to pancakes when he returned to his artillery battery. For syrup, Denius’s cook boiled some sugar in water until it thickened.

The defenders of Hill 314, known as the “Lost Battalion,” looked like ghosts to the men who relieved them. They were gaunt after six days of hunger. Of the approximately 700 defenders, only 376 survived. Casualties totaled 277 killed, wounded, and missing. Two out of every five American soldiers were casualties.

The Battle of Mortain proved the resilience of the American soldier in a crisis. The men had not panicked when surrounded and fought on despite low stocks of ammunition and food. The enemy had them so outnumbered and outgunned that Maj. Gen. Hobbs later claimed: “With heavy onion breath that [first] day, the Germans would have achieved their objective.”

The brutal battle also brought together the men of the battalion like never before. “Guys who used to bitch at and fight each other became brothers,” explained Pfc. Joseph Perry after the battle.

The battle at Mortain also proved the importance of artillery. During the standoff, the battalion’s supporting artillery fired an average of 2,000 shells in a 24-hour period. Those rounds landed on German tanks, trucks, and soldiers.

The GI newspaper Stars & Stripes reported Lieutenant Kerley’s blunt surrender refusal two weeks after the battle, but it never really stuck. General Anthony McAuliffe’s “Nuts” response, delivered some five months later at the besieged Belgian town of Bastogne, became the rebuke heard round the world. The men of the Old Hickory who heard Kerley’s response shared it with everyone on Hill 314 but kept it to themselves. The two best-known books about Mortain, Victory at Mortain by Mark Reardon and Saving the Breakout by Alwyn Featherston, both claim that Kerley’s response was “short, to the point, and very unprintable.” Neither author reveals what Kerley actually said.

The battle for Mortain was more important than just a hilltop stand. While the men of the 2nd Battalion held on by their fingernails, Patton’s XV Corps raced 75 miles behind German lines. American commanders did not panic when the Germans attacked. Instead, they dealt with the situation while sticking to their plan of surrounding the entire German Seventh Army in Normandy. The fruits of Mortain would be harvested in the victory in the Falaise Pocket.

Frequent contributor Kevin M. Hymel is a historian for the U.S. Army’s Combat Studies Institute at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas, and author of Patton’s Photographs: War as He Saw It. He also leads tours of Patton’s battlefields (including Mortain) and personal tours of Normandy for Stephen Ambrose Historical Tours.

My Dad was in the 30th Division, he said they armed cooks, supply men everybody to fight as they thought they may get overrun by the Germans!