By Joseph Balkoski

Editor’s Note: The following is excerpted from Omaha Beach: D-Day June 6, 1944 by Joseph Balkoski (Stackpole Books, 2004; www.stackpolebooks.com). It takes up the story where, owing to bad weather, bombers fail to blast the beach, and the first assault—by tanks—is launched. It then describes the earliest landings of Rangers and the 116th Infantry Regiment. Balkoski’s account weaves narrative with first-person accounts taken from statements before D-day, orders, or after-action reports.

A note on terminology: Neptune is the name of the amphibious portion of the Overlord attack. LCVPs (landing craft, personnel) and LCAs (landing craft, assault) each held about 30 men; LCMs (landing craft, mechanized) held one tank or 50 men; LCTs (landing craft, tanks) held three or four tanks; and LCT(A)s (landing craft, tank [armored]) were LCTs with increased armor.

A Device Called Duplex Drive

Ever since the Germans had unleashed blitzkrieg in 1939, British and American generals had come to believe in the tank as a necessary ingredient of any offensive military operation. But the Allies would initially have to attack from the sea to gain a toehold in Europe, and in such an endeavor, tanks would seemingly have little or no immediate role. An operation as hazardous as Neptune, however, demanded innovative solutions to the immense challenge of landing a large military force on a hostile shore, and if the Allies could come up with a way to employ tanks in the early stage of an amphibious assault, Neptune’s chance of success would increase dramatically. It required a monumental effort to devise and produce special equipment that would enable tanks to land in the invasion’s first wave, but that effort would be well worth it if those tanks could help crack open the Atlantic Wall.

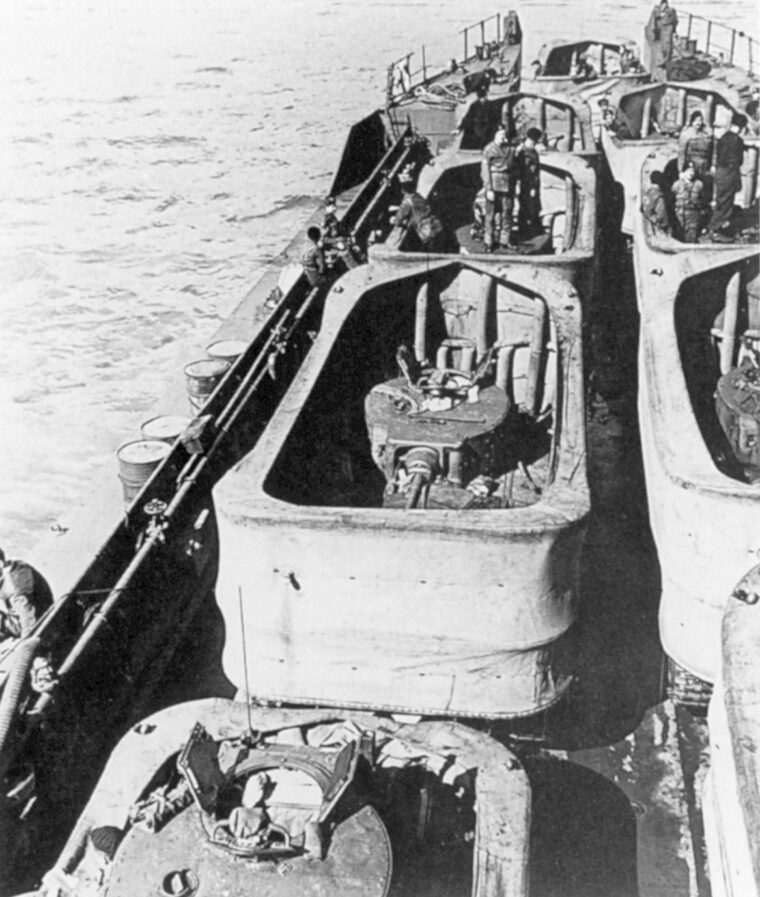

For years the British had advocated the use of special armored vehicles in amphibious warfare, and with their help, Generals Gerow and Bradley resolved to land 112 specially modified U.S. Army Sherman tanks on Omaha Beach before a single infantryman set foot in France. According to Gerow’s plan, sixteen U.S. Navy LCT landing craft would launch a total of sixty-four duplex drive (DD) Shermans about three miles offshore. These tanks would proceed shoreward under their own power, landing on Omaha Beach at 6:25 A.M., five minutes before H-Hour. In the meantime, another sixteen armored LCT(A)s were to proceed straight to the beach, grounding themselves in the shallow surf to deposit forty-eight more Shermans onto the sand over the landing craft’s bow ramps.

If this ambitious and unprecedented scheme actually worked, exultant GIs emerging from their landing craft minutes later would observe Shermans churning across the beach, spaced at intervals of roughly sixty yards, their big 75-millimeter cannons and machine guns blasting away at enemy pillboxes. Even if the occupants of those pillboxes survived the tanks’ onslaught, the Shermans would make excellent shields against enemy fire as the foot troops hastily crossed the beach. And if enemy barbed wire or obstructions blocked the infantry’s path, the tanks could handily remedy that situation too. Many were convinced that the tanks could be the much-needed modifiers that altered the amphibious warfare equation in favor of the invaders. But a few harbored misgivings that the tank plan sounded too good to be true.

Maj. Gen. Leonard T. Gerow, Commander, V Corps, Overlord Conference, December 21, 1943

I don’t know whether it has been demonstrated or not: What will happen to those DD tanks with a three- or four-knot current? … I question our capability of getting them in with that current and navigation.

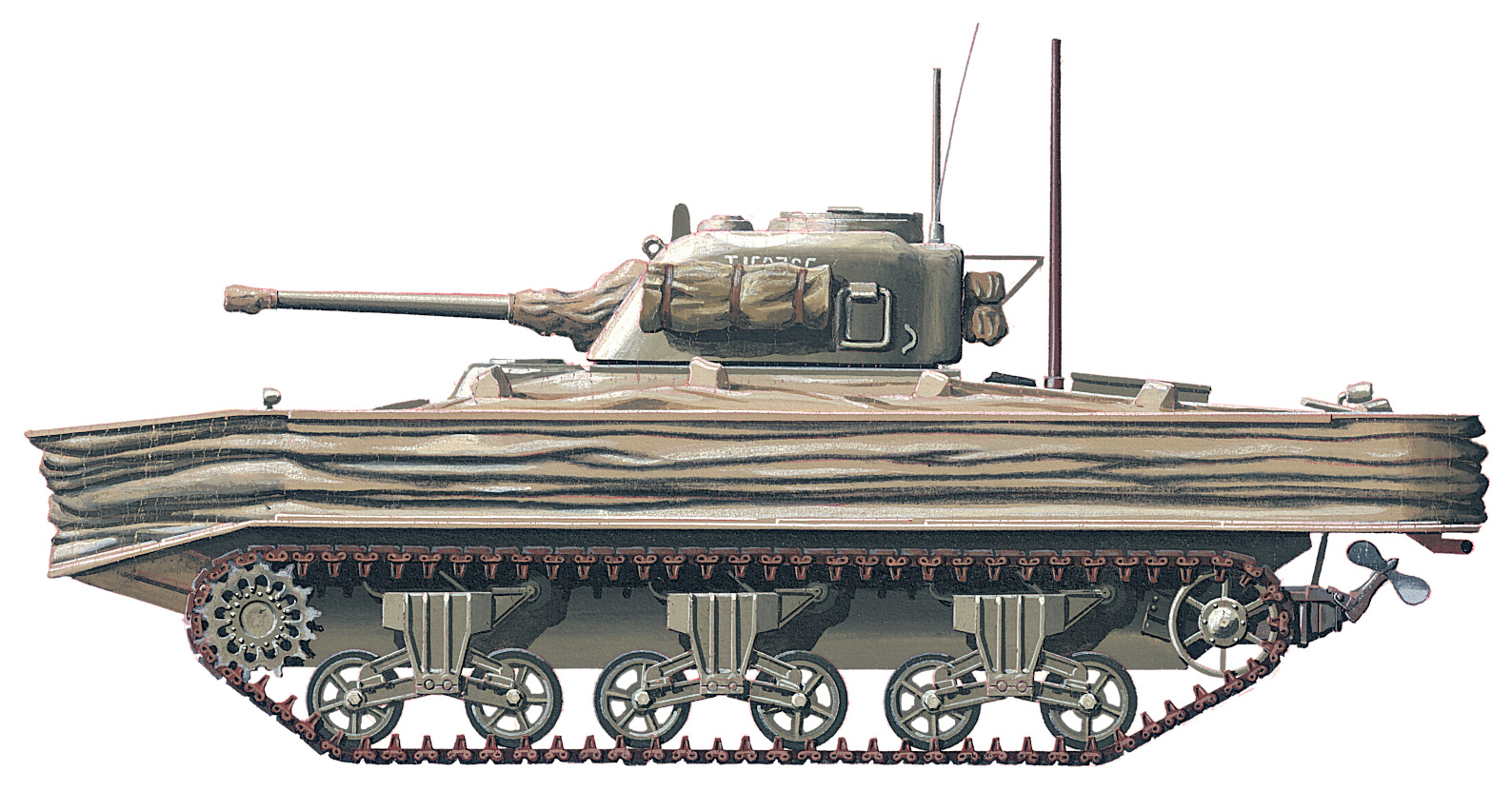

In a war noted for its technological innovations, the DD tank stands as one of the most curious developments of World War II. One would not expect a thirty-three-ton Sherman tank to be capable of driving off an LCT into the sea and then cruising to shore under its own power, but that is exactly what a DD tank was intended to do. A shroud made of rubber and canvas supported by metal struts enabled the tank to float; the duplex drive transmission powered two propellers, which also acted as rudders, for sea movement, although speed was a meager five miles per hour. Once on land, the driver switched the transmission to power the treads rather than the propellers, and the tank proceeded to travel on solid earth.

The Americans had learned to operate DDs from British Army personnel in early 1944 and were satisfied with the tanks’ performance—in practice. A DD tank in the water with its shroud raised was almost entirely submerged; less than one foot of canvas remained above the water to prevent the sea from swamping the vehicle. The uninitiated would not have the slightest idea that a tank lay hidden behind that canvas, for a DD at sea had the slightly ludicrous appearance of a floating bathtub, lacking any imaginable military application whatsoever.

Maj. William Duncan, S-3, 743rd Tank Battalion, top secret DD Tank Report, April 30, 1944

The following are limitations of the DD tank: A) It is given flotation by a very tender skin of canvas. This canvas is easily torn … A tear greater than one foot may cause the tank to sink. B) The DD tank is limited to a maximum of Force 3 wind and sea. C) It is believed that a DD tank can be sunk by wash of LCT, LCS, and larger craft passing within a few yards of the tank. D) Six cases of carbon monoxide poisoning have been noted in launches of 4,000 yards or greater. No fatalities.

Lt. Dean Rockwell, Commander, U.S. Navy LCT Group 35, Evaluation of DD tank, April 30, 1944

I should like to make the following recommendations. … A) That the Army be notified immediately of the LCTs by number that will be assigned to each tank battalion. This is imperative for future training to prepare for D-Day. B) Inasmuch as the Army is desirous of launching, if at all possible and feasible, the DD tanks on D-Day, an Army officer who is thoroughly cognizant of the limitations and peculiarities of said tanks should make the decision, in case of rough sea, whether or not the tanks shall be launched or taken directly to the beach. C) That the DD tanks be used on D-Day.

Duncan and Rockwell trained three tank battalions with these new secret weapons for the invasion. On Omaha, two would be employed: The 741st would swim thirty-two DDs ashore on the eastern half of the beach, and the 743rd would swim in thirty-two on the western half.

1st Lt. Edward Sledge, Company A, 741st Tank Battalion

[I recall] the complete confidence of the men in our tanks … In all our training in England, we had not lost one DD tank.

The two tank outfits were almost indistinguishable: They handled the same equipment; followed identical training procedures; and shared the same mission. Their D-Day experiences, however, were anything but identical. The proficient tankers in both the 741st and 743rd were anxious to demonstrate their DD tanks’ worth, but they also realized that these were delicate machines. Major Duncan had warned that Force 4 or worse wind and sea conditions could be disastrous for the DDs, and tankers and sailors who heeded this warning surely noted that at dawn’s early light on D-Day, Force 4 conditions—eleven- to sixteen-knot winds and waves of three to five feet—seemed to be in effect.

The LCTs carrying the DD tanks had endured a tough Channel crossing. As H-Hour loomed, the task at hand promised to be even tougher. The 741st and 743rd had vital missions to fulfill, but given the current sea conditions, someone would have to make some difficult decisions. At 5:30 A.M., as the LCT columns wallowed at a speed of four knots through the dark, choppy sea toward Omaha Beach, now about three miles distant, the moment for that judgment had come.

Launch the DD tanks at sea or take them straight to the beach? Despite the parallel upbringings of the two tank outfits, their fates would diverge dramatically as a result of the choices soldiers and sailors were about to make.

Force O, U.S. Navy, Top secret Neptune orders, LCTs carrying DD tanks, May 1944

Weather permitting, launch DD tanks about 6,000 yards offshore and land them at about H-10 minutes [6:20 A.M.]. If state of sea is such as to prevent their being launched and proceeding to the beach under their own power, land them with the first wave.

741st Tank Battalion, Loud-hailer message to LCT-602, carrying four 741st DD tanks, 0520 hours, June 6, 1944

You are 5,500 yards from the beach. It’s up to your DDs now!

Ens. J. H. Metcalfe, Action Report, LCT-601, carrying 4 DD tanks of 741st Tank Battalion, June 1944

The tank corps men appeared confident of being able to reach the beach.

741st Tank Battalion, After-Action Report, July 19, 1944

At approximately H-60 [5:30 A.M.] the LCTs bearing the DD tanks of Companies B and C were in position off beach Omaha at a distance of approximately 6,000 yards from the beach. Company B was commanded by Capt. James Thornton, Company C was commanded by Capt. Charles Young. Capt. Thornton succeeded in contacting Capt. Young by radio and the two commanders discussed the advisability of launching the DD tanks, the sea being extremely rough—much rougher than the tanks had ever operated in. … Both commanders agreed that the advantage to be gained by the launching of the tanks justified the risk of launching the tanks in the heavy sea. Accordingly, orders were issued for the launching of the tanks at approximately H-50 [5:40 A.M.].

Maj. William Duncan, S-3, 743rd Tank Battalion

Any Force 4 sea with choppy waters and waves of two feet or over were very dangerous, and Lt. Rockwell, USN, and the crews on his LCTs were well trained and very well aware of the danger. However, the Army directed that the senior captains of each battalion involved in the actual DD landing would make the decision on the spot as to whether to launch or not. Capt. Ned Elder (a wonderful officer), CO, Company C, 743rd Tank Battalion, determined that because of the heavy seas, the Navy LCTs should take the 743rd tanks to the beach.

Lt. Dean Rockwell, Commander, U.S. Navy LCT Group 35, Action Report, July 14, 1944

It was apparent that the sea would not be ideal for launching of the tanks. Before leaving Portland the question had been raised by this command as to the course to pursue in the event of a sea too rough for launching. Despite the insistence of this command that a decision be made by one senior army officer for both battalions, the question of launching was finally left to the senior army officer of each battalion, in this case Capt. Thornton of the 741st and Capt. Elder of the 743rd. This decision was agreed upon by Lt. Cols. Skaggs and Upham, commanding the 741st and 743rd, respectively. At 0505 this command contacted Capt. Elder via tank radio, and we were in perfect accord that the LCTs carrying tanks of the 743rd Battalion would not launch, but put the tanks directly on the designated beaches.

S/Sgt. Paul Ragan, Company B, 741st Tank Battalion, aboard LCT-600, July 1945

I saw the yellow flags go up, which meant to start launching. The ramp went down, and the first tank went off. I watched it clear the ramp and turned my head to start giving instructions to the other ones and at that time there was a big explosion near our craft, and all the tanks were pushed against each other and tore the screens. … [I saw] that the only tank that went off the LCT had sunk. The water was very rough. I went to the skipper and said that we must pick the men up. … We picked them up, and I also noticed a lot of others who were in life rafts, but we had to go on to the beach to drive our tanks off; this we did.

Ens. R. L. Harkey, Action Report, LCT-602, carrying four DD tanks of 741st Tank Battalion, June 1944

I am not proud of the fact, nor will I ever cease regretting that I did not take the tanks all the way to the beach.

On LCT-549, a concerned Lieutenant Barry had expressed doubt that his embarked DDs could successfully launch, but the tankers decided to try anyway. The first three tanks that drove off LCT-549’s ramp sank after swimming only about 100 yards. Even after observing this disaster, Sgt. John Sertell, in charge of the fourth and last tank remaining on LCT-549, decided to launch despite an obvious tear in the canvas shroud of his DD. Said the astonished Barry, “It was a vain hope.” Later that day, another LCT picked up Sertell’s body.

The decision to launch the DD tanks of the 741st Tank Battalion at sea proved calamitous. All sixteen of Company C’s tanks sank on the way to the beach, with the loss of considerable numbers of men. Only two of Company B’s tanks made it to shore under their own power, although by sensible agreement of Ens. Henry Sullivan and 2nd Lt. P. J. O’Shaughnessy, LCT-600 later carried three more tanks directly to the beach after the unsuccessful launch of its first DD. The infantrymen of the 1st Division would therefore be lacking twenty-seven of the thirty-two DD tanks that the top brass had promised would be waiting for them on the beach at H-Hour. The men of the Fighting First would miss them greatly.

But thanks to Elder and Rockwell, the eight LCTs carrying Companies B and C of the 743rd made it to the beach without launching a single DD tank at sea. All eight landing craft successfully touched down at about 6:40 A.M., only a short time after the DD tanks had been scheduled to land. A few of Rockwell’s LCTs experienced problems off-loading their tanks, for the beach was now under heavy fire, but in large measure most of the 743rd’s DDs churned through the shallow surf toward the ominous belts of enemy beach obstacles dead ahead. The tanks were roughly where they were supposed to be, and the GIs of the 29th Division would sorely need them.

Over There, Again

Gerow’s skepticism of the DD tanks—now proved valid—had led him to devise an invasion plan that did not depend entirely on duplex drive technology to deposit tanks in front of the infantry on Omaha Beach. A complementary scheme dictated that at H-Hour, sixteen ex-British LCT(A)s, enhanced with extra armor plating and still painted in the mostly white camouflage pattern favored by many Royal Navy landing craft, would each land three tanks directly on the beach over special ramp extensions meant to ease the task of disembarking vehicles in the deep surf. Two of the three tanks would be conventional Shermans; the third would be a Sherman specially fitted with a bulldozer blade to clear barbed wire and beach obstacles. To enable these tanks to land and operate in surf up to about seven feet deep, they had been specially waterproofed and had large metallic intake and exhaust ducts shaped like inverted fishhooks mounted over the rear engine.

Sailors assigned to a vessel that the navy had upgraded with supplementary armor harbored suspicions that they would be the invasion’s proverbial guinea pigs—and they were right. Gerow’s invasion diagrams could not be more blunt: The LCT(A)s would be the first landing craft to touch down on Omaha Beach. Intelligence summaries were equally blunt: The Germans had many large-caliber guns deployed in pillboxes, some rumored to be dreaded “88s,” whose shells had sliced through Allied tanks in North Africa with astonishing precision even at ranges of a mile or more. If the preassault aerial and naval bombardment failed to produce results, the life expectancy of LCT(A) crews on Omaha could be very short.

Army tankers embarked on the LCT(A)s were less fatalistic. Tanks were designed to pave the way for the infantry, so their D-Day mission was not received with much surprise. If any Germans survived the bombardment, the tanks could disperse, take cover in the deep surf, and blast away at the enemy from there. For men who had drawn one of the invasion’s toughest assignments, the tankers were surprisingly confident of success.

But the plan fell apart almost immediately. The arduous Channel crossing had caused many LCT(A)s to scatter, and in the predawn darkness off Omaha Beach, it proved impossible for them to gather in their proper assembly areas prior to the run to the beach.

Capt. Lorenzo Sabin, Commander, U.S. Navy Gunfire Support Group, Force O, Action Report, July 3, 1944

As we were behind schedule, all craft proceeded directly towards the beach at utmost speed and made no attempt to proceed to a position in front of the transport area and thence to the beach.

In addition to their treacherous fundamental mission, overwhelmed LCT(A) skippers were ordered to extend minesweeping gear on the approach to the beach—a task some simply ignored. They were also responsible for towing large LCM landing craft across the Channel, an obligation that no doubt contributed to the breakdown of their assembly schedule. About three miles off the beach, embarked army demolition engineers were supposed to shift from the LCT(A)s to the LCMs, an awkward procedure in the dark, rough seas off Calvados, and both landing craft would then head for the beach independently.

Burdened by so many hazardous tasks, Commander Sabin could hardly have been surprised that only ten of his sixteen LCT(A)s scheduled to land at 6:30 A.M. actually made it to the beach on time and successfully put their tanks ashore. The Germans promptly greeted them by opening fire with every weapon within range. For the LCT(A)s, an already risky mission suddenly became considerably riskier.

Capt. Lorenzo Sabin, Commander, U.S. Navy Gunfire Support Group, Force O, Action Report, July 3, 1944

During the approach to the beach, LCT(A)-2229 was sunk, presumably due to flooding, at a position about two miles off Dog Red beach. Two officers, four [enlisted] men, and three Army personnel were lost.… There was not much opposition from enemy defenses until the craft were right at the beach. At that time, a heavy barrage of shell, mortar, and machine gun fire was laid down.

Ens. Victor Hicken, Officer-in-command, LCT(A)-2227, Gunfire Support Group, Force O

On Dog Green, we landed “smack on,” as the British would say, and right on time [6:30 A.M.]. On Dog Green there is a little spit which hooks out beyond the beach. We landed there and immediately drew mortar and machine gun fire. The tanks were discharged, but we couldn’t get the anchor winch to retract. We were all huddled down in the wheelhouse, which was armored, listening to machine gun bullets hitting. A mortar shell blew off the ramp, and at that moment the heavy fire eased. I think Company A, 116th Regiment [29th Division] was landing and took the fire from us. In a sense we were saved by their sacrifice.… I will always remember a seaman coming up from below, shouting: “The mattresses are on fire!” With my foot I pushed him on the helmet and told him to go back and put out the fires. He did.

On a wide-open beach, the Shermans stood little chance against enemy antitank guns sited in fortified positions on commanding ground, all of which had easily survived the aerial and naval bombardment of the coast. To prove that point, one DD tank of the 743rd Tank Battalion brought directly to the beach as per Elder’s and Rockwell’s orders was knocked out by a screeching enemy antitank shell only seconds after driving down LCT-591’s bow ramp. To destroy the enemy pillboxes, the tanks would have to work in concert with the infantry, but lacking that support, they would be trapped on a beach with no exit, to be picked off one by one like the proverbial fish in a barrel. To postpone this fate, most tanks sought concealment in the shallow surf and returned fire from that skimpy cover as the tide rose. Across more than 400 yards of open beach, however, the well-concealed enemy pillboxes were nearly impossible to detect, and for the moment, the tankers could do little except wait for more favorable conditions to recommence their attack—assuming they could survive that interval. Unhappily for Bradley and Gerow, only a few minutes after H-Hour, the Germans proved themselves fully capable of thwarting the large numbers of tanks the Americans had deployed in the invasion’s first wave. At least in this instance, tanks would not alter the balance of amphibious warfare in favor of the invader after all.

S/Sgt. Thomas Fair, Company A, 741st Tank Battalion, June 1944

The ramp was dropped in pretty deep water and we left the craft. I was in Number 1 tank, and Sgt. Larsen had Number 2 tank, and the dozer was Number 3. The water was up over our turret ring. We finally pulled up on the beach, but still stayed in the water enough for our protection. Our bow gunner and gunner started spraying the trees and hillside with .30 caliber [machine gun fire] while we looked for antitank guns and pillboxes.

Cpl. S. Schiller, Company A, 741st Tank Battalion, June 1944

Lt. [Gaetera] Barcelona’s tank, named “Always in My Heart,” upon approaching the beach was firing continuously upon targets. The main target was a house to the right of Exit E-1, into which several rounds were fired. After leaving the landing craft, our first target was a pillbox of a 75mm [antitank gun], which was stopped after [we fired] several rounds of high explosive.

T/5 Robert Jarvis, Company B, 743rd Tank Battalion

When we first came down the ramp of the LCT, we started firing immediately at whatever pillboxes or targets we could see. Being the assistant gunner, I didn’t have much time to look out of my periscope [as I was] loading the 75mm cannon and the .30 caliber machine gun. I would get a call for AP [armor piercing] for pillboxes or HE [high explosive] for what looked like trenches or a machine gun nest …. I finally had a few slack moments in firing to look around. I figured by our firing that the beach should be pretty well secured. … As I was watching, the surf rolled a body of a sailor alongside of our tank. I recognized the sailor as being one of the crew of our LCT.… It was then that I realized everything was not going according to schedule.

Enclosed within their vehicles’ steel hulls, with a severely limited field of vision, the tankers had a profound sense of isolation. What was going on? No one had the slightest idea—but if the tanks did not clear the beach soon, they stood a good chance of being turned into flaming wrecks. Help, in the form of American GIs, was on the way.

Editor’s Note: The following except describes the story of C Company, 2nd Ranger Battalion, and Company A, 116th Infantry Regiment, 29th Division landing on Omaha Beach at H-Hour.]

THE MOMENTOUS NOW

Top Men at Their Craft

For the foot soldiers who were about to storm Festung Europa, the first close-up view of the French coast was alarming. Where were the bombers? The top brass had promised that the shoreline would be smoldering from the Eighth Air Force’s cascade of bombs, but the beach was obviously intact, and as smooth as slate. True, the naval shelling had been impressive, but it had hardly lasted long enough to accomplish much.

As the beach drew closer, troops and sailors peering over the sides of their landing craft could distinguish the terrain features they had been briefed so thoroughly about—but aside from some friendly tanks floundering in the shallow surf, the beach and coastal bluffs displayed no signs of life. Staff officers had assured the GIs that the Germans defending the beach were second-rate troops. Perhaps the brief naval barrage had caused most of the enemy to flee. Evidence of the Germans’ presence here, however, was obvious: Hundreds of menacing beach obstacles loomed beyond the surf, among them wooden poles, steel tetrahedrons, and bulky metal gates—most of which were allegedly mined. If the enemy had indeed survived the naval barrage, the GIs of the first wave could not fail to notice that crossing that expanse of open beach under fire would be anything but easy.

It did not take long for the Germans to announce their presence. Foamy white geysers, apparently produced by mortar or howitzer shells, suddenly erupted from the sea amid the ragged lines of landing craft racing toward the beach, now just a few hundred yards distant. No machine gun fire yet—but the landing was clearly not going to be a walkaway after all.

Coxswains raced their engines, steering their landing craft through the rolling breakers toward touchdown points on the beach. Their wretched three-hour journey from transport to shore about to end, many desperately seasick men could barely wait to place their feet on solid ground again regardless of what the enemy had to offer. At a time like this, typical soldier chatter hardly seemed appropriate—just a reassuring glance at a buddy and a faint smile or nod in return would do. The landing craft’s engines were too loud to permit normal conversation anyway. Nervous infantrymen adjusted equipment that had already been readjusted a dozen times, and as their craft noisily jolted to a halt, the men gripped their weapons tightly and prepared to carry out the job they had been trained to do.

Sub-Lt. Jimmy Green, Wave commander, Royal Navy 551 Assault Flotilla, Embarking Company A, 116th Infantry

It was approaching the time to form line abreast and make our dash for the shore. I gave the signal and told Signalman Webb to stop pumping and take cover. [Coxswain] Martin pulled down the cover over his head and was guided by me through slits in his armor-plated cockpit. … Now we were alone, at the right beach at the right time. Taylor Fellers [CO, Company A, 116th Infantry] wanted to be landed to the right of the pass [Vierville draw]. We went flat out and crunched to a halt some 20 or 30 yards from the shoreline and 100 yards below the nearest beach obstacles.

2nd Lt. John Spalding, Company E, 16th Infantry, 1st Division, February 1945

The Navy had been firing, and the dust from debris plus the early morning mist made it difficult to see the coast …. As we came in there was considerable noise from the shore and sea. En route to the shore we passed several yellow rubber boats. They had personnel in them, but we didn’t know who they were. They turned out to be tank personnel from the DD tanks which had foundered .… About 0630 we hit the line of departure; someone gave a signal and we swung into line. When we got about 200 yards offshore, the boat halted and a member of the Navy crew yelled for us to drop the ramp. S/Sgt. Fred A. Bisco and I kicked the ramp down.

Those foot soldiers who were lucky enough to have survived the initial landing at Omaha Beach would forever define D-Day by their experiences in the invasion’s first few minutes. The first wave was transported to its destination—and its destiny—in fifty small landing craft, more than a quarter of them British. Each craft embarked at least 31 soldiers, yielding a force of more than 1,550 GIs to shoulder the burden of introducing the U.S. Army to the German occupiers of France at precisely H+1 minute, 6:31 A.M.

Omaha Beach was a big place. The first wave would land on a front of more than four and a half miles. Dispersed over such great length, the initial invaders might feel lonely at first, but thousands more comrades-in-arms would shortly follow in their wake. Of the fifty landing craft, twenty-four carried members of the 16th Infantry, 1st Division, to the eastern half of the beach; another twenty-four brought troops from the 116th Infantry, 29th Division, to the western half. The remaining two craft would convey Company C of the 2nd Ranger Battalion to Omaha’s westernmost extremity, a sector Neptune planners had designated “Charlie.”

When the army had created its elite Ranger units in World War II, Charlie was precisely the type of place where it planned to employ them. This was a foreboding and lonely sector, seemingly a cul-de-sac with the ocean on one side and cliffs higher than 100 feet on the other. At high tide, there was no beach save for a belt of boulders only a few feet wide. But the Rangers had been trained to consider cliffs and boulders as nothing more than temporary impediments. In fact, at the same time Company C stormed ashore on Omaha Beach, three more Ranger companies from the 2nd Battalion were scheduled to ascend similar cliffs at Pointe du Hoc, a critical objective four miles westward down the Calvados coast.

That Company C was a decidedly confident outfit was demonstrated when, in one of the two Royal Navy LCAs transporting them to the beach, the Rangers acknowledged Sgt. Walter Geldon, who was celebrating his third wedding anniversary, by singing in his honor. Geldon would be dead in less than an hour.

Capt. Ralph Goranson, Commander, Company C, 2nd Ranger Battalion

I was fortunate to have, in my humble pride, the best damn group of Rangers in the 2nd Battalion. I also felt that the Royal Navy and its landing craft were the very best. They beached us on time in the best place—exactly per our instructions. And they paid dearly for it.

In the Charlie sector, the beach abruptly terminated in a rocky promontory the locals called Pointe de la Percée. There the Germans had erected an apparently impregnable strongpoint atop the cliff, consisting of at least four pillboxes surrounded by two belts of barbed wire. Only a highly confident soldier could have imagined that sixty-five men landing by sea could capture such a position in daylight, but that was precisely what Company C was obliged to do. Such a treacherous mission could be accomplished only by soldiers who knew exactly what they were doing, but Goranson was certain that these were the type of men who populated his company. The task was critical. No American on Omaha Beach could move without being observed by the enemy from the Percée headland. Goranson’s Rangers would be responsible for seeing to it that the enemy did not enjoy that advantage.

Captain Goranson devised two different attack plans. According to Plan One, Company C would shift eastward down the beach after landing and move inland through the Vierville draw, assuming 29th Division troops had already cleared that exit. The Rangers would then move west along the coast road and attack the enemy strongpoint from the landward side. However, if the 29ers had not yet seized the draw, Goranson would trigger Plan Two, a much more challenging scheme requiring the Rangers to ascend the sheer cliffs overlooking Charlie prior to moving inland around the strongpoint. Even if only a few Germans survived the preinvasion bombardment to resist the GIs from the clifftop, Plan Two would be extraordinarily difficult to execute, especially as Goranson’s men lacked most of the specialized climbing gear that their fellow Rangers would deploy at Pointe du Hoc.

The LCA carrying Goranson was the westernmost of the fifty first-wave landing craft. Consequently, it drew attention from the German beach defenders, who indeed had survived the Allied bombardment. As the Rangers neared Omaha Beach, they stopped singing.

Capt. Ralph Goranson, Commander, Company C, 2nd Ranger Battalion

I told the men to get from the water’s edge under the overhang of the cliffs as fast as they could because that’s where safety will be … Right after we landed we took at least three or four rounds of 88s. The first was wide, but number two took the landing ramp off. Number three hit in the rear, and number four amidships.

The Rangers’ worst fears had been immediately realized: the enemy was decidedly active and seemingly had every foot of the beach zeroed in. Goranson had a wrecked LCA and a dozen casualties to prove it, and not a single Ranger had thus far set foot on Omaha Beach. Was another Dieppe imminent?

On Company C’s second landing craft, as the Royal Navy coxswain raced his engine for the final run to the beach, Lt. Sidney Salomon noticed sharp, metallic pings on the side of the LCA: machine gun fire. When the LCA grounded, Salomon was the first through its narrow armored door and down the bow ramp. Sgt. Oliver Reed followed but was immediately felled by a bullet. As the rest of the boat team trudged off the LCA, Salomon grabbed Reed’s collar and dragged him through the waist-deep surf to dry sand. But the worst was yet to come….

1st Lt. Sidney Salomon, Company C, 2nd Ranger Battalion

After going a short distance, a mortar shell landed behind me, killing or wounding my mortar section, the concussion knocking me forward and on the ground. I thought that I was dead. … Just then sand was kicked in my face; I assumed that an enemy machine gunner was getting me in range, and decided that I had better move. I got up and ran to the base of the cliff.

PFC Nelson Noyes, Company C, 2nd Ranger Battalion

We went out onto the beach, and the Germans had us zeroed in. We waded in about a foot of water. … All of us ran across the beach as fast as we could. I ran about 100 feet before hitting the ground, when we ran into enemy crossfire from the right and in front.

Burdened by equipment and waterlogged uniforms, the Rangers found it hard to move swiftly across the soft sand, and the Germans cut many more of them down—including First Sergeant Golas and Sergeant Geldon. The stunned survivors who reached the base of the cliffs noted that more than half of the original sixty-five Rangers had failed to make it that far. In front of the Vierville draw off to his left, Goranson could observe tanks and 29th Division troops on the receiving end of even heavier enemy fire.

If the Rangers still had a job to do, the proper course of action was obvious. Lt. William Moody needed only to glance at Goranson and ask, “Plan Two?” Goranson replied, “Right.” Reduced to about thirty men, the Rangers would climb the cliffs.

Accompanied by Sgt. Julius Belcher and PFC Otto Stephens, Moody followed the cliff base westward for about 300 yards. There they found a section of cliff that just might do. Stephens climbed first, thrusting his bayonet into the cliff face to gain successive holds. Belcher and Moody followed and brought up four sections of toggle rope to anchor on the cliff top, thereby easing the climb for any followers. The Rangers’ war would begin from there.

PFC Otto Stephens, Company C, 2nd Ranger Battalion, Distinguished Service Cross Citation, June 1944

Proceeding across the fire-swept beach PFC Stephens scaled a 100-foot cliff and secured ropes to the top for other men to use in ascending. Without waiting for his comrades to reach the top, PFC Stephens proceeded to attack the enemy positions located there.

Captain Fellers’ Boys

The invasion plan hinged on the quick seizure of the Vierville draw, but the 29th Division unit with the mission to capture it faced a tactical dilemma just as challenging as the Rangers’ task on Charlie. Gerow prized the draw because it was Omaha’s best beach exit, featuring a good, hard-surfaced road that connected to the vital coastal highway at Vierville, only 500 yards inland.

The enemy, too, grasped the significance of the draw and fortified it with a fervor unmatched anywhere else on Omaha Beach. Packed into a front of only 600 yards, the Germans had constructed three autonomous strongpoints on ground so commanding that troops who attempted to move up the draw would be enveloped in a crossfire that would in all probability kill them all. At the draw’s mouth, a concrete wall 9 feet high, 6 feet thick, and 125 feet long protruded from a massive pillbox situated on an embankment just beyond the beach, blocking all movement inland. Another pillbox sited slightly lower on the same embankment, about 100 yards to the west, had two apertures that allowed it to fire along the beach in either direction. The entire resistance nest in front of the draw was surrounded by barbed wire and minefields, and its fighting positions were interconnected with trenches. With an efficiency for which the Germans were celebrated, they had ensured that no American soldier in the invasion’s first wave would get anywhere near the Vierville draw.

Sub-Lt. Jimmy Green, Wave commander, Royal Navy 551 Assault Flotilla, Embarking Company A, 116th Infantry

As we neared the shore I picked out a nasty looking pillbox and hoped it was not manned. … I was watching [the pillbox] and thinking that if it was manned we were going to be in trouble. There was a loud bang in my right ear, and I turned to see an LCG [landing craft, gun—probably USS LCG-424, with Royal Marine gun crews] blazing away with its 4.7-inch guns and scoring direct hits on the pillbox. I wished it could have stayed longer, but it disappeared as quickly as it had arrived.

The outfit drawing the assignment for this impossible mission was Company A, 116th Infantry, an old Virginia National Guard unit with highly treasured traditions harking back to Jackson and his legendary Stonewall Brigade, both fundamental icons of the Confederacy’s “Lost Cause.” Raised in the picturesque village of Bedford in the foothills of the Blue Ridge, the old Company A men styled their outfit “The Peaks of Otter Rifles” after the nearby summits known by all Virginians for their natural beauty. On February 3, 1941, Company A had been abruptly converted from a group of 98 part-time militiamen into an active component of the U.S. Army. By D-Day, more than three years later, the army had made over Company A, and the Bedford guardsmen who had survived this transformation amounted to only a small minority—35 men out of the outfit’s full complement of 210. However, most of the company’s key leaders, including its commander, Capt. Taylor Fellers, its executive, Lt. Ray Nance, and 1st Sgt. John Wilkes, were Bedford men, as were many senior noncommissioned officers.

Six Royal Navy LCAs under Green’s command, all drawn from the British transport Empire Javelin, carried Fellers’ Company A to its H-Hour appointment on Dog Green Beach. Fellers was suffering from the lingering effects of a nasty sinus infection that had nearly forced him to miss the invasion. He asked Green to land his men astride the mouth of the Vierville draw, three LCAs on either side. Green correctly surmised that the taciturn Fellers was troubled by the gravity and danger of his mission. Indeed, Fellers had recently blurted to Nance that, armed with a single machine gun, one enemy infantryman could hold off the entire company from the heights straddling the draw—and if the bombardment failed to work, Company A would be wiped out. Like Gerow, Fellers was a realist.

Green pledged his support. His landing craft crews were brave and highly competent, and they would take the Americans exactly where they wanted to go, on schedule. Unlike U.S. Navy LCVPs, Green’s British LCAs were armored and could stop rifle and machine gun bullets. They also provided some measure of overhead protection and featured benches on which the GIs could sit during the long run to shore. Once Fellers’ men disembarked, however, Green’s craft would have to depart—and Company A would be on its own.

Misfortune struck Company A just before it landed, as the LCA in column immediately behind Green’s swamped about 1,000 yards offshore due to an apparent leak. As the LCA disappeared beneath their feet, the men activated carbon dioxide capsules to inflate their life belts and waged frantic life-or-death struggles to shed heavy equipment before the sea swallowed them forever. Only one man, radio operator PFC Jim Padley, drowned. He was last seen on the crest of a swell, and then he was gone. The rest would later be rescued by Green and returned to Empire Javelin. Down to five boat teams, Fellers’ already difficult task had suddenly become even more daunting.

The Royal Navy, as promised, landed Company A on time on either side of the draw. On each of the five surviving LCAs, a crewman kicked open the steel door and dropped the bow ramp into the surf with a cracking splash. The men yearned to get off, but on an LCA, they would have to be patient; the steel door in the bow was narrow enough to permit only a single file of soldiers to exit at once, as opposed to three files in an American LCVP. Led by Fellers, and accompanied by simple exhortations of “Good luck!” from the British, the heavily laden GIs shuffled down the ramps into frigid waist-high water, holding their weapons aloft. Despite the lack of evidence that the Eighth Air Force had visited this beach, the men retained hopes that most of the enemy had fled with their first glimpse of the vast Allied armada. Could it be true? So far the Germans had offered mostly inaccurate mortar fire. Green observed every soldier exit his LCA safely and advance through the surf to the water’s edge-still no enemy machine guns. Having done his duty, Green ordered his signalman to radio Empire Javelin: “Landed against light opposition. On target.”

The men of Company A emerged from the water and pressed forward onto the beach. Off to the left, some Shermans were visible in the surf. A profuse jumble of German obstacles lay dead ahead, seemingly strewn randomly on the sand. Nearly 300 yards beyond them, the Vierville draw loomed. Company A needed only to seize that draw to accomplish its mission. But on an embankment directly between the GIs and their objective lay two sinister enemy pillboxes, apparently intact. Those 300 yards would seem a lot longer to Fellers and his men if the pillboxes suddenly turned active.

As Green prepared to return to Empire Javelin, he noted that Dog Green Beach was for the moment tranquil. Only the thud of waves smacking ashore and occasional shouts of command could be heard. On the beach, the men of Company A flopped into prone positions in a scraggly line just short of the obstacles, while Fellers, at the far right of the line, conferred with some of his noncommissioned officers. Meanwhile, the tide surged forward, so rapidly that it seemed to exhort the Americans to push ahead.

And then all hell broke loose.

No one could tell where the enemy machine gun fire came from; only its distinctive rrrrrrrp, like a rag being torn, was audible. But no one could fail to notice its obvious effects, as thousands of bullets kicked up spouts of sand around the startled GIs, many of whom were promptly hit. A German machine gun spewed out 1,200 bullets per minute, and at that rate, it could kill a lot of Americans in a hurry—especially on a beach with no cover and no craters.

Fellers was probably one of the first to die, but it is impossible to determine how, because every member of his thirty-one-man boat team died with him. It was a slaughter. Of the 155 Company A soldiers who had just exited the LCAs, close to 100 died on Omaha Beach, and most of the rest were wounded. Nineteen of the dead were Bedford men, including a pair of brothers. Those few who survived did so only because they hastily retreated neck-high into the surf or hid behind some of the tanks located at the water’s edge.

Company A, 116th Infantry, 29th Division, U.S. Army Historical Division, interview with PFC Leo Nash, September 1944

[Lt. Edward Tidrick] went on to the sands and flopped down fifteen feet from PFC Leo J. Nash. He raised up to give Nash an order. Nash saw him bleeding from the throat and heard his words: “Advance with the wire cutters!” It was futile. Nash had no wire cutters, and in giving the order, Tidrick had made himself a target for just an instant, and Nash saw machine gun bullets cleave him from head to pelvis. German machine gunners along the cliff directly ahead were now firing straight down into the party.

Company A, 116th Infantry, 29th Division, U.S. Army Historical Division, interview with PFCs Nash, Murdoch, and Grosser, September 1944

A medical boat team came in on the right of Tidrick’s boat. [This was probably Company A’s seventh LCA, led by Lt. Ray Nance, the company’s executive officer. It was scheduled to land thirty minutes after the first six LCAs, but it beached about twelve minutes early. It had three medics, two of whom were killed.] The Germans machine-gunned every man in the section. [A few survived, including Nance and the third medic, Cpl. Cecil Breeden.] Their bodies floated with the tide. By this time the leaderless infantrymen had foregone any attempt to get forward against the enemy, and where men moved at all, their efforts were directed toward trying to save any of their comrades they could reach. [Witnesses noted Breeden treating several Company A wounded under heavy fire.] The men in the water pushed wounded men ahead of them so as to get them ashore.

One of the Bedford natives who perished by Fellers’ side was S/Sgt. Elmere Wright, one of the most accomplished athletes in the 116th Infantry. Wright was a superb pitcher who had led the 116th Infantry’s baseball team to the 1943 European Theater championship with a perfect 27-0 record. He had played minor league baseball in the St. Louis Browns’ organization before the war, and after his dominating 1943 performance, he was delighted to hear from a Browns executive that a major league career was a distinct possibility upon his return to the States. In a 1943 team photograph, Wright’s cheerful visage reveals a man who eagerly looked forward to that chance. The enemy saw to it that he would never get it.

So few Company A soldiers survived that it was almost impossible for wartime U.S. Army historians to determine precisely how the debacle had unfolded. In recent years, however, the reality of Company A’s fate has become more clear. Captain Fellers had been correct: Only a few Germans—perhaps two or three machine gun teams—were responsible for the company’s destruction. The primary source of the killing was probably an enemy pillbox camouflaged nearly perfectly in the folds of the bluff about 200 yards west of the Vierville draw. This pillbox was sited to fire only eastward, and through its firing slit, occupants had an ideal view of the beach where Company A disembarked. At about 400 yards range, a German manning a fixed machine gun with a perfect flank shot could hardly miss.

The men of Bedford had trained for almost three and a half years for this moment, only to be cut down in seconds like stalks of wheat felled by a scythe. Despite promises of unprecedented levels of support, Company A died alone. Eighth Air Force bombs had not hit the beach; the navy’s guns had not knocked out the enemy’s pillboxes; and aside from a few dozen Rangers racing to the cliffs on their right, not a single friendly infantryman was in sight. n

Joseph Balkoski is the author of Beyond the Beachhead: The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy and an historian specializing in the Normandy campaign. He resided in Normandy during the summer of 2001 and now lives in Baltimore, Maryland.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments