By Christopher Miskimon

The fate of the American Revolution seemed bleak indeed in December 1776. New Jersey was on the verge of collapse with many of its residents swearing new oaths of loyalty to Great Britain. General George Washington implored Maj. Gen. Charles Lee to join their forces together, but the call went unheeded. When Lee was captured by British cavalry on December 13, Washington quickly took command of Lee’s 4,000 troops. Congress, situated in Philadelphia, was unimpressed by this action and abandoned the city, retreating to Baltimore. Congressman William Whipple blamed the citizens of Philadelphia, saying they were in such a panic it infected some of the politicians. Alarm and fear seemed to be the order of the day, as many expected the fledgling rebellion to fail.

While those around him fretted and dithered, Washington went into action. The British had a series of outposts around the countryside, established to protect Loyalists. The British leadership was overconfident. Washington perceived their outposts were vulnerable, and he moved to strike them. He chose to strike the outpost of Trenton, New Jersey, which was garrisoned by three regiments of German mercenaries. In the early hours of December 26 his army crossed the Delaware River and struck Trenton, killing or capturing 974 men. This victory enabled him to convince his men to reenlist for another six weeks.

He used that time to take further offensive moves, using a night march to get behind the British and defeat three of their regiments at Princeton, New Jersey, on January 3, 1777. Afterward, Washington feinted at the main British supply depot at New Brunswick, New Jersey, forcing his enemy to rush to its defense. Yet again the American general was shrewd, electing not to engage in a set-piece battle to his disadvantage. He retired with his troops to Morristown, where they went into winter quarters. The British were stung by these defeats. Washington quickly issued a proclamation offering the local citizens a chance to return to the American side by swearing their allegiance at the nearest military post.

This was an example of George Washington’s ability to accurately estimate the military situation and take advantage of it. In general he was expert at choosing when to defend, attack, or even withdraw. Despite this genius for engaging in a winning strategy, he was often derided and even plotted against by his contemporaries, who either sought his position for themselves or believed he was unable to achieve the victory they all sought. They could not see that Washington’s strategy was aimed at ultimate victory, not simply winning battles his enemies could afford to lose. He knew the American Revolution would continue as long as the rebels had an army in existence, no matter how many battles it lost or how far it had to march. Keeping his army together was always his focus. If it was not necessary to fight, he avoided battle. If retreat was the best option, he took it; however, when he saw the chance to turn and strike his foes from a position of relative advantage and security, he seized that chance as well.

This was an example of George Washington’s ability to accurately estimate the military situation and take advantage of it. In general he was expert at choosing when to defend, attack, or even withdraw. Despite this genius for engaging in a winning strategy, he was often derided and even plotted against by his contemporaries, who either sought his position for themselves or believed he was unable to achieve the victory they all sought. They could not see that Washington’s strategy was aimed at ultimate victory, not simply winning battles his enemies could afford to lose. He knew the American Revolution would continue as long as the rebels had an army in existence, no matter how many battles it lost or how far it had to march. Keeping his army together was always his focus. If it was not necessary to fight, he avoided battle. If retreat was the best option, he took it; however, when he saw the chance to turn and strike his foes from a position of relative advantage and security, he seized that chance as well.

How George Washington created his professional army and kept it in the field until victory was achieved is the subject of Thomas Fleming’s new book, The Strategy of Victory: How General George Washington Won the American Revolution (Da Capo Press, Boston, MA, 2017, 310 pp., photographs, notes, index, $28.00, hardcover). It highlights the creation, successes, and failures of the Continental Army under its famous leader. The Continental Army succeeded despite appalling hardships and seemingly unbeatable odds.

Fleming’s work is insightful. It gets right to the heart of Washington’s actions in a passionate argument of his virtues as a leader. The author is a leading authority on Washington and this period of American history. His clear language and thoughtful ideas succeed in getting his message across and make this book a pleasure to read. It gives the reader an understanding of the reasons George Washington is considered the father of the United States. Without his vision, drive, and stoic determination, the history of North America would have been decidedly different.

Combat Talons in Vietnam: Recovering a Covert Special Ops Crew (John Gargus, Texas A&M Press, College Station, 2017, 272 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

Combat Talons in Vietnam: Recovering a Covert Special Ops Crew (John Gargus, Texas A&M Press, College Station, 2017, 272 pp., maps, photographs, appendices, notes, bibliography, index, $35.00, hardcover)

The first Combat Talons were specially modified C-130 cargo aircraft designed to support Special Forces operations in Vietnam. They were developed in secrecy and used advanced electronics and equipment to make them better able to fly at low level during the night. The author was a mission planner for the unit operating the Combat Talons and oversaw many successful assignments; however, one night an aircraft did not come back. It was lost with all 11 crewmen aboard. Their families were told nothing due to the secrecy around the unit’s activities. It stayed that way for the next 30 years.

After a memorial to the lost crew was raised in the late 1990s, the author decided to investigate, hoping the files had been declassified. He discovered the plane had been found in 1992 and the crew’s remains were in Hawaii. This led to a deeper investigation around the circumstances of the recovery. This book tells the story of that investigation. It is also partly an autobiography of the author’s time in Vietnam. The story is revealed in a gripping narrative that shows the everyday details of life in the unit along with the bigger story of the lost aircraft. Much of what the author found is reproduced in a series of appendices so the reader can read the original documents as well.

Snipers at War: An Equipment and Operations History (John Walter, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2017, photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

Snipers at War: An Equipment and Operations History (John Walter, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis MD, 2017, photographs, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

The Battle of Spotsylvania Court House was in full fury on May 9, 1864. Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick, the commander of the Union VI Corps, was directing his troops under fire, oblivious to the occasional bullets flying around him. His infantrymen ducked as the incoming fire zipped past. Sedgwick berated them for trying to dodge the rounds.

A soldier moving past ducked for another bullet. “They couldn’t hit an elephant at this distance,” said Sedgwick. The soldier good-naturedly told the general he had dodged an incoming shell once and so was a believer in dodging. Seconds later an incoming bullet from a Whitworth Rifle struck home with a slapping sound. Sedgwick turned toward his aide. A hole was visible under his left eye. Without uttering a word, he fell against the aide, knocking them both to the ground. Although at least two Confederate soldiers claimed credit, the exact identity of the sharpshooter remains unknown.

The sniper is a popular character in modern media, but the path to the modern sharpshooter was one of centuries of development. The training, weapons, equipment, and uniforms of specialized marksmen came together through extensive experimentation and battlefield usage. This book is a thorough and scholarly history of the sniper. It is well written with many useful examples. It is also a veritable treasure trove of technical data on the craft of the sniper.

India’s Wars: A Military History 1947-1971 (Arjun Subramaniam, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2017, 576 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $40.00, hardcover)

India’s Wars: A Military History 1947-1971 (Arjun Subramaniam, Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, MD, 2017, 576 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $40.00, hardcover)

On December 18, 1961, Martin B-57 Canberra bombers of the Indian Air Force arrived over Dabolim airfield in the Portuguese enclave of Goa. The relatively new nation of India had repeatedly asked Portugal to give back the territory it had held on the Subcontinent for more than 400 years, but that European nation consistently refused. India was taking the region back by force. The Canberras bombed the airfield while an Indian infantry division and armored regiment, supported by paratroopers, crossed into the territory. Some Portuguese fought, but many surrendered to the vastly superior Indian force. The fledgling Indian navy shelled Portuguese defenses before putting ashore a landing force that met stiff resistance, but was ultimately victorious. Within a few days Goa was Indian. The Portuguese were furious at what they considered the theft of their colony while India celebrated its liberation.

The battle for Goa was an early example of a combined operation for the Indian military, combining land, air, and sea elements. It is one small piece of a growing heritage for that nation, a history that is well told in this book. The work is impressive in its readability and clarity, as the author does not presume any foreknowledge of his subject and strives to make clear a subject relatively unknown in the Western world. The work deftly traces India’s military origins in the 20th century.

The Blue and Gray Almanac: The Civil War in Facts and Figures, Recipes & Slang (Albert Nofi, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2017, 346 pp., photographs, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover)

The Blue and Gray Almanac: The Civil War in Facts and Figures, Recipes & Slang (Albert Nofi, Casemate Publishers, Havertown, PA, 2017, 346 pp., photographs, appendix, notes, bibliography, index, $32.95, hardcover)

On the morning of July 21, 1861, the men of the 1st Minnesota Volunteer Infantry were marching into action at the Battle of First Bull Run. When the unit stopped for a brief rest, they saw an old African American gentleman adorned in the tattered remains of a Revolutionary War uniform waving an American flag. They spoke to him and he told them he was once a drummer boy for George Washington. Many of the men were abolitionists and they chatted with him during their rest. When the regiment was called back into ranks to resume the march, one man asked the old soldier to say a blessing for the unit. The elderly veteran asked God to watch over the regiment and make it strong for the coming fight. That day the 1st Minnesota helped repulse three attacks on Henry House Hill and was the only Union regiment to have to be ordered to retreat. The unit also suffered heavy casualties and fought well at Gettysburg two years later. The surviving men of the unit would often attribute their stalwartness in battle to the old man’s prayer.

Such interesting anecdotes and stories are frequently retold about the American Civil War, and this new work collects a number of them together. It keeps the reader’s interest through a dozen well-written chapters, each covering a different facet of the war.

The Martyr and the Traitor: Nathan Hale, Moses Dunbar, and the American Revolution (Virginia DeJohn Anderson, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2017, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover)

The Martyr and the Traitor: Nathan Hale, Moses Dunbar, and the American Revolution (Virginia DeJohn Anderson, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2017, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, index, $27.95, hardcover)

The Revolutionary War had only just begun when two men began fateful journeys in September 1776. Nathan Hale was a soldier in the Continental Army who disguised himself as a schoolmaster and secretly went into British-occupied Manhattan. He made sketches and took notes and gave them to George Washington, who was his commander. The other man was Moses Dunbar, who accepted a commission as a captain in a loyalist regiment in New York. Afterward, he returned home to Bristol, Connecticut, to raise recruits for the British cause.

Both men were arrested for their activities. Hale was hanged very quickly on September 22, 1776. Dunbar was given a trial, found guilty, and went to the gallows on March 19, 1777. Hale is recalled to this day as a martyr for the American cause, while Dunbar is regarded as a traitor.

The two men came from fairly similar backgrounds and a comparison of the two is the subject of this book. The author seeks to answer how these men went in such different directions and how easily their legacies might be reversed if the revolution had been quashed. She also examines how their decisions became mixed with politics of the day. The book effectively showcases both sides of what was a bitter conflict with many injustices perpetrated by both sides.

Voices from the Past: The Siege of Sevastopol 1854-1855 (Anthony Dawson, Frontline Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index $34.95, hardcover)

Voices from the Past: The Siege of Sevastopol 1854-1855 (Anthony Dawson, Frontline Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, 288 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index $34.95, hardcover)

The Crimean War was an incredibly difficult conflict for the Anglo-French armies and those of their allies. The terrible winter weather combined with outbreaks of both cholera and dysentery and more than 90,000 Allied troops died due to their combined effects. The siege of Sevastopol of 1854-1855 took place in this miserable period. It was a time of huge artillery bombardments, desperate attacks upon defensive positions, and interrelated battles occurring nearby. At one point the Russians blew up defenses they could not keep even though they still had troops manning them. The explosion caused the largest man-made hole in history up to that date.

The author has collected a large amount of previously unpublished material for this new work. Entries from private letters and journal are mixed with French sources previously unused in the English-speaking world. The result is a work that effectively conveys the thoughts and experiences of the participants to the reader.

Chitral 1895: An Episode of the Great Game (Mark Simner, Fonthill Media, UK, 2017, 224 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

Chitral 1895: An Episode of the Great Game (Mark Simner, Fonthill Media, UK, 2017, 224 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $34.95, hardcover)

In 1895 a small force of Indian troops was garrisoning the fort of Chitral on the Northwest Frontier. They were commanded by a pair of British officers, a captain and a surgeon-major. The tribes of the region were always hostile toward the occupying British and their Colonial troops and this led to an attack on the fort by a combined army of Pathan and Chitrali tribesmen, which vastly outnumbered the defenders. Unable to breach the defenses outright, the attackers laid siege to the fortress. A relief expedition was quickly organized, but it had to fight its way to Chitral to affect a rescue. Despite difficulty the garrison was nevertheless able to hold out for 48 days. The events at Chitral were a small but significant part of the so-called Great Game played out between Russia and Great Britain for control of the region during the late 19th century. The battle played its part in a later uprising two years later.

Both the siege and relief expedition are covered in detail in this new work by the author, who has several previous books published on the wars of this era. The descriptions of the harsh weather, difficult terrain, and stubborn fighters all blend together to give the reader a clear idea of the hardships faced by the combatants during this time. The result is an interesting look at a little-known battle with far-reaching consequences for the British Empire in this region.

The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy and Extraordinary Heroism (John U. Bacon, William Morrow Books, New York, 2017, 418 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $29.99, hardcover)

The Great Halifax Explosion: A World War I Story of Treachery, Tragedy and Extraordinary Heroism (John U. Bacon, William Morrow Books, New York, 2017, 418 pp., maps, photographs, notes, bibliography, index, $29.99, hardcover)

World War I was grinding into its fourth year when the French cargo ship Mont-Blanc set sail from the Brooklyn docks in New York City. It was loaded with six million pounds of high explosives. The captain so feared an explosion he forbade his men from smoking or even lighting a match. He even had the freight secured with copper nails since they do not spark when struck. The ship underwent a four-day voyage through a snowstorm to reach Halifax, Nova Scotia on December 6, 1917. It arrived at the relief ship Imo was departing. At 8:46 am the Imo collided with the Mont-Blanc, striking its bow and knocking over barrels of aviation gasoline. A fire broke out and the crew quickly evacuated.

At 9:04 am the Mont-Blanc exploded, killing 2,000 people, wounding 9,000, and rendering 25,000 homeless. A 2.5-square-mile section of the city was leveled. It was the largest explosion in history until the detonation of the first atomic bomb 28 years later on August 6, 1945. This unknown tragedy of the war is brought to light in this new book, which delves into the personal stories of those who experienced it and how the event affected the nations involved.

Offa and the Mercian Wars: The Rise and Fall of the First Great English Kingdom (Chris Peers, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, 240 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, softcover)

Offa and the Mercian Wars: The Rise and Fall of the First Great English Kingdom (Chris Peers, Pen and Sword Books, South Yorkshire, UK, 2017, 240 pp., maps, photographs, bibliography, index, $29.95, softcover)

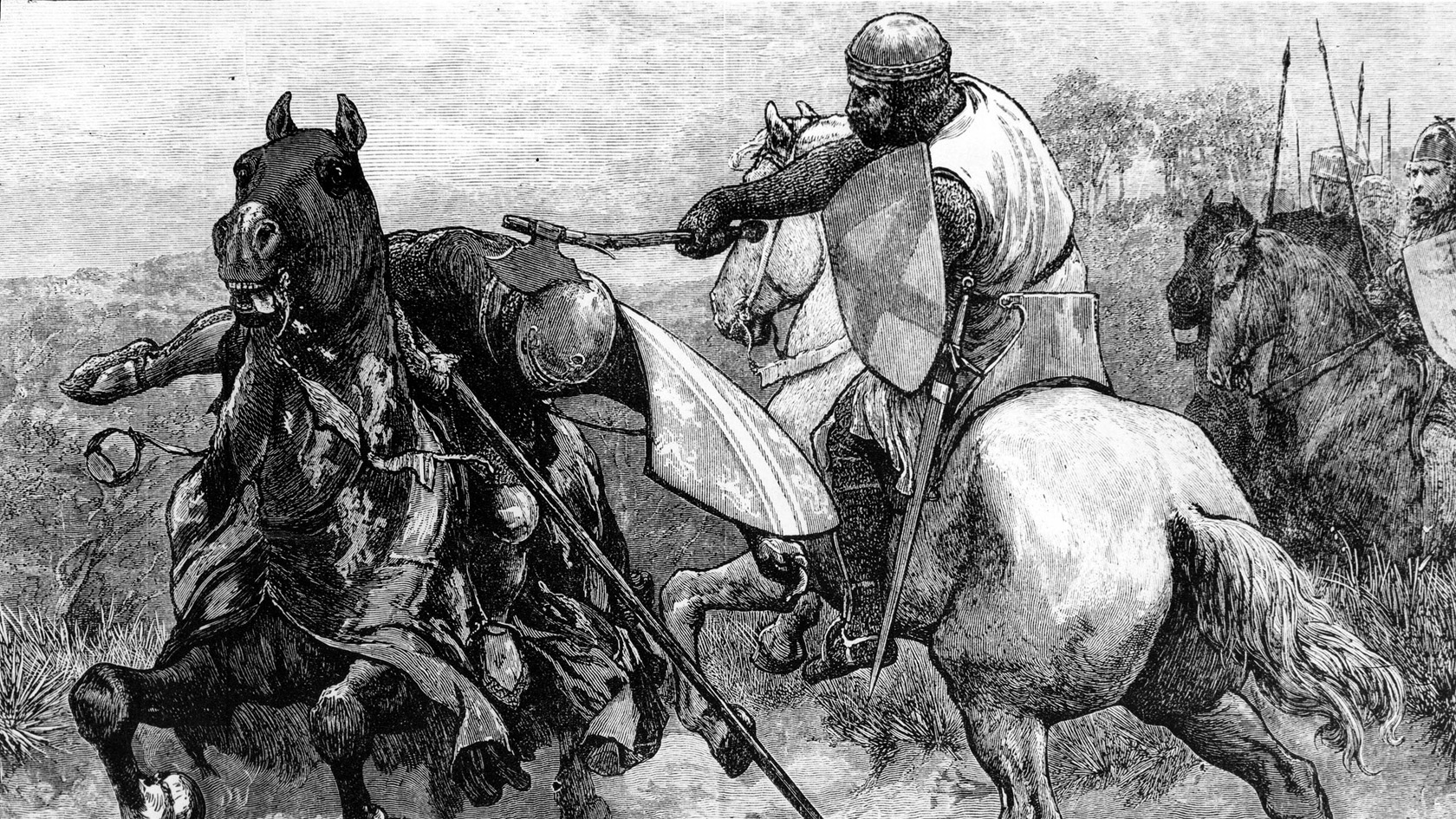

In 8th-century England Offa was the ruler of the Kingdom of Mercia, the most powerful of the Anglo-Saxon realms. For more than 30 years he was the greatest warlord south of the Humber Estuary and successfully strove to increase the power of his nation. He fought numerous campaigns against the neighboring lands of Wessex and Northumbria along with the Welsh tribes. His reign was a long one and Mercia enjoyed a substantial rise before the appearance of the Danes more than a century later.

This new work by an acknowledged expert on ancient warfare and military organizations sheds light on Offa and his kingdom. It sets the man into the greater context of English history and the part Mercia played in what would become the United Kingdom. Much about this period is unrecorded but the author effectively fills in the gaps through his extensive research. Often histories of England begin with the Norman Conquest, but this work effectively argues that England was truly created hundreds of years earlier.

Short Bursts

The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War and Emancipation in the Heart of America (Edward L. Ayers, W.W. Norton and Company, 2017, $35.00, hardcover) This book provides a new examination of the relation between the end of slavery and the Civil War. It tells of the end of the Confederacy and the rebirth of the nation.

The Thin Light of Freedom: The Civil War and Emancipation in the Heart of America (Edward L. Ayers, W.W. Norton and Company, 2017, $35.00, hardcover) This book provides a new examination of the relation between the end of slavery and the Civil War. It tells of the end of the Confederacy and the rebirth of the nation.

Emory Upton: Misunderstood Reformer (David J. Fitzpatrick, University of Oklahoma, 2017, $39.95, hardcover) A new biography of one of America’s most important military reformers. He professionalized the army while upholding the American ideal of the citizen-soldier.

A Waste of Blood and Treasure: The 1799 Anglo-Russian Invasion of the Netherlands (Philip Bell, Pen and Sword, 2017, $34.95, Hardcover) In the early years of the Napoleonic Wars, Great Britain allied with Russia to force Republican France out of the Netherlands. It was a dramatic campaign that ended in failure.

Berlin Blockade: Soviet Chokehold and the Great Allied Airlift 1948-49 (Gerry Van Tonder, Casemate Publishing, 2017, $22.95, softcover) The first clash of the Cold War occurred when the Soviet Union tried to cut off access to West Berlin. Through a supreme American effort, the Communist operation failed.

Pirate Alley: Commanding Task Force 151 off Somalia (Terry McKnight and Michael Hirsch, Naval Institute Press, 2017, $29.95, softcover) The U.S. Navy continues to carry out operations against Somali pirates. One of the authors was the task force’s first commander.

The Path to War: How the First World War Created Modern America (Michael S. Neiberg, Oxford University Press, 2017, $29.95, hardcover) Over the course of World War I, the United States went from an isolationist nation bent on staying out of the conflict to a full participant. This book details that transformation.

Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (B.H. Liddell Hart, Frontline Books, 2017, $17.95, softcover) The author is one of history’s great military theorists. He offers keen insight into one of antiquity’s greatest generals.

Scipio Africanus: Greater Than Napoleon (B.H. Liddell Hart, Frontline Books, 2017, $17.95, softcover) The author is one of history’s great military theorists. He offers keen insight into one of antiquity’s greatest generals.

First Founding Father: Richard Henry Lee and the Call to Independence (Harlow Giles Unger, Da Capo Press, 2017, $28.00, hardcover) Richard Henry Lee was the first to call for independence and held the Continental Congress together during the conflict. This biography highlights his achievements.

Warship 2017 (Edited by John Jordan, Conway Books, 2017, $60.00, hardcover) This impressive annual is a hallmark of scholarly naval history. It offers an in-depth look at a wide variety of naval vessels and naval warfare systems.

Mapping Naval Warfare: A Visual History of Conflict at Sea (Jeremy Black, Osprey Publishing, 2017, $45.00, hardcover) Jeremy Black is a renowned scholar of Renaissance history. In his latest work he examines key naval conflicts from the 16th century to the present day and explores how maps helped naval commanders craft their strategies.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments