By William E. Welsh

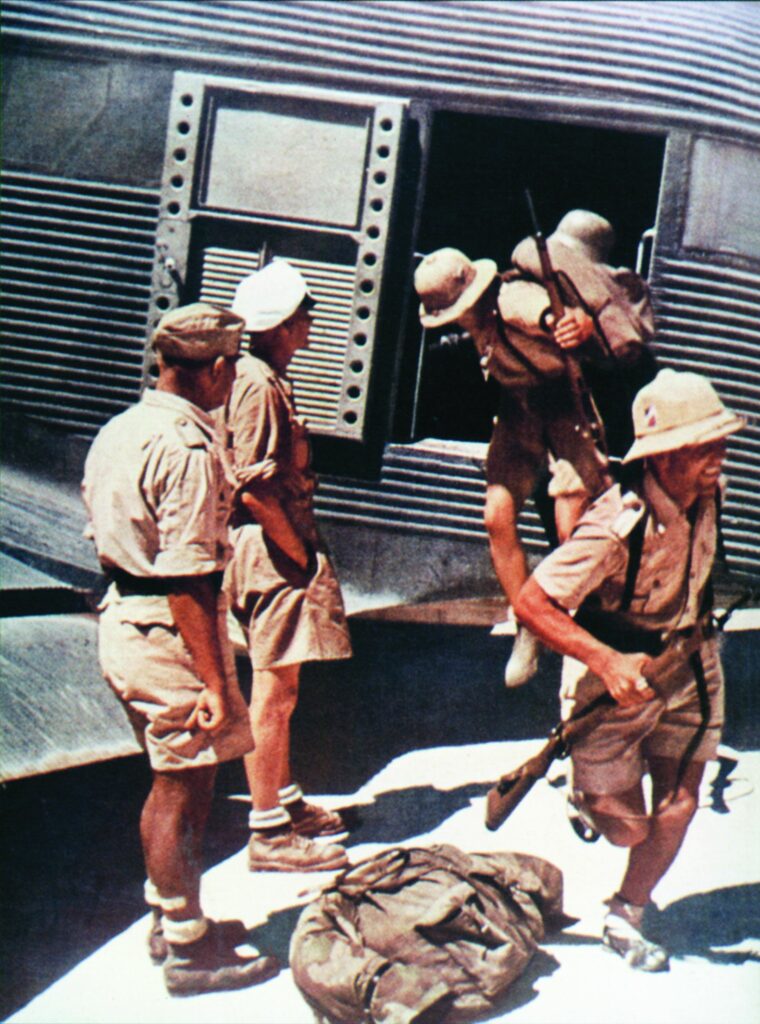

Shortly before dawn on May 20, 1941, a flight of 500 transport planes took off from seven airstrips on mainland Greece. As they climbed upward, the tri-motor aircraft emerged from reddish-orange clouds of dust into blue sky. The dust clouds were generated by the propeller wash from hundreds of engines sitting on unpaved runways as the planes prepared for takeoff. Inside each aircraft, a dozen German paratroopers sat hunched on canvas benches sweating profusely inside their heavy uniforms. Each one welcomed the cool air that swept through the cabins once the aircraft were aloft.

The planes lumbered in tightly packed formations at low altitude over the pale blue waters of the Aegean Sea toward their objective. Once they crossed the coast of enemy-held Crete, they were greeted by a storm of flak that rocked the planes as if they were trees in the wind. Ignoring the turbulence, the veteran paratroopers stood up, shuffled toward the cargo door, and flung themselves spread eagle toward the ground below. Once the flight crews had delivered their human cargo to its destination, they turned their aircraft back toward the mainland to load the next wave. Operation Mercury, the largest airborne invasion the world had yet seen, was without doubt the finest hour of the Junkers Ju-52 transport, known to its crews as “Tante Ju,” or Auntie Junkers.

The Ju-52: A Commercial Aircraft

The Ju-52 was originally envisioned as a commercial venture in 1925 by Deutsche Lufthansa. The concept moved from paper to production when the project was turned over to Junkers in 1928. Its chief designer, Ernst Zindel, oversaw work on two concepts. One was a single-engine freight aircraft (Ju-52/1m) and the other was a three-engine commercial passenger plane (Ju-52/3m) built to carry 17 passengers.

The first single-engine Ju-52 made its maiden flight on October 13, 1930. It was followed six months later by the three-engine version’s maiden flight in April 1931. After just a few years in service, production of the single-engine version came to an abrupt halt in 1934, but the three-engine version, which offered better safety and considerably more power, captured the interest of Lufthansa as well as international customers that used the aircraft for both passenger and freight purposes.

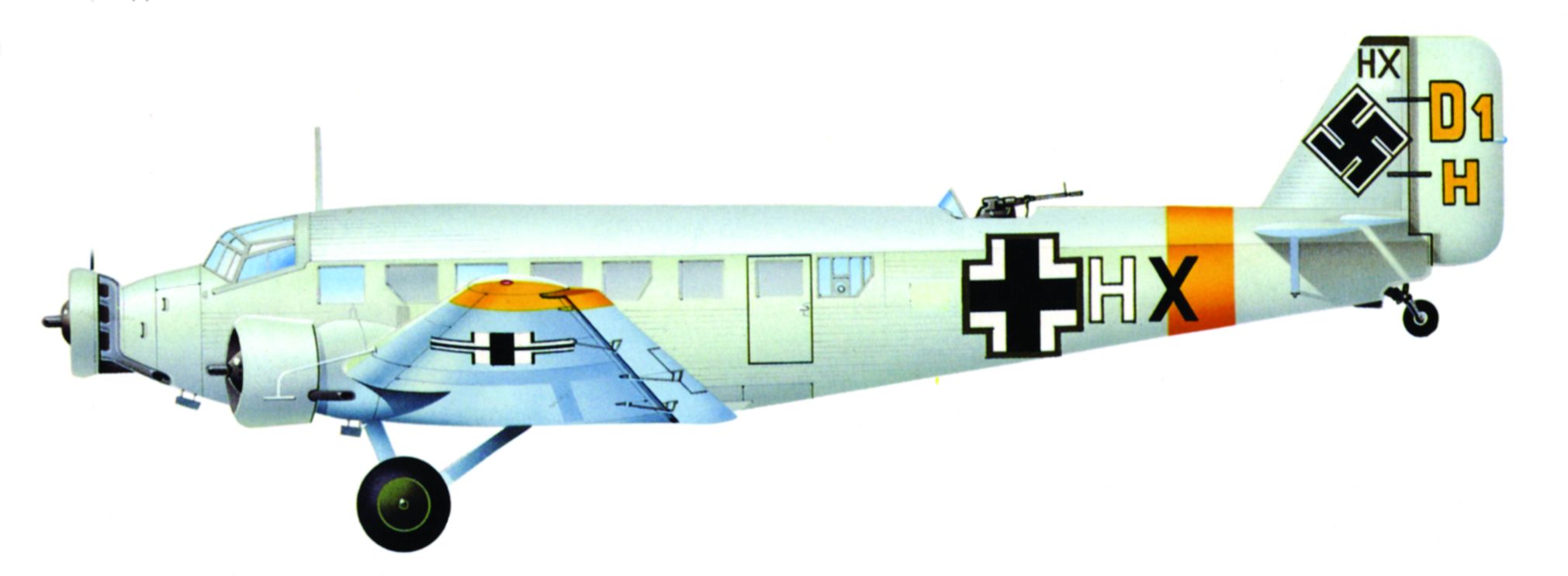

The Ju-52/3m had a wing span of 29.5 meters and measured 18.9 meters from nose to tail. The all-metal plane (80/20 magnesium/ aluminum) was easily recognized not only by its three-engine configuration but also by a box-like, corrugated fuselage that gave it an almost unfinished appearance.

Deutsche Lufthansa began flying the Ju-52/3m on heavily traveled commercial routes, such as Berlin to London and Berlin to Rome in late 1932. Twenty-five countries throughout Europe and North and South America purchased the aircraft for commercial use during the 1930s. For 13 years from 1932 to 1945, the Junkers German factories produced Ju-52 variants. It was during its first few years in operation that the Ju-52 earned the endearing nicknames “Tante Ju” and “Eisen Annie” (Iron Annie) because of its reliability and performance that resulted in few forced landings and the need for minimal repair work.

Militarizing the Ju-52

When Adolf Hitler was elected chancellor of Germany in 1933, the future German dictator instructed the Air Ministry to put a plan into action to build a 1,000-plane air force. He did this despite the fact that Germany was prohibited from having any military aircraft through the Treaty of Versailles. Rather than develop an entirely new transport aircraft, the ministry ordered the conversion of a large number of existing aircraft from civilian to military use.

Minimal alteration was required. The Ju-52/3m freight version had a hatch in the roof for loading by crane, a large cargo door on the starboard side just behind the wing, and a door for passengers on the port side. A new hole was cut into the roof to accommodate a dorsal machine gun, and the interior was reconfigured for different missions.

The Ju-52/3m began its military service as a bomber during the Spanish Civil War. During the blitzkrieg period of World War II from 1939 to 1941 it served in a support role by delivering paratroopers to their targets, towing gliders carrying assault troops, and transferring air landing troops to captured airfields. After the invasion of Crete in May 1941, the airplane was used primarily for delivering fuel, ammunition, and supplies to troops in forward areas or isolated pockets and evacuating wounded.

A military version of Eisen Annie, designated the Ju-52/3mg3e was ready for service in 1934. While a version designated the Ju-52/3m Sa3 was already operating for the Reichswehr in the role of personnel transport, cargo carrier, and pilot trainer, the g3e was intended as an interim bomber before more sophisticated bombers were available in 1936. The military version was powered by three 660hp BMW 132A radial engines and armed with dorsal and ventral 7.92 MG 15 machine guns, the latter of which was affixed to the aircraft’s underside with a retractable dustbin attachment. When fully loaded, whether with troops or supplies, the aircraft had a top speed of 171 miles per hour and a cruising speed of about 120 miles per hour. The Ju-52/3m’s round-trip range carrying a 1,984-pound load was 720 miles. This range increased to 900 miles with a lighter load (992 pounds) or decreased to 450 miles with a heavier load (3,306 pounds).

The Ju-52/3m was equipped with robust landing gear that enabled it to take off and land on dirt or grass strips as short as 400 meters that other aircraft could not use. What is more, the metal structure could withstand considerable punishment, which enabled the crews to complete their missions and limp back to safety when damaged.

First Combat in Spain

Shortly after the Spanish Civil War broke out in July 1936, Hitler sent 20 Ju-52/3ms in September to support Nationalist General Francisco Franco in his struggle against the Republican forces on the Iberian peninsula. During the conflict, Eisen Annie served in a dual role of troop transport and interim bomber. Two years before, the Reichswehr (the Luftwaffe was not reconstituted until 1935) had requested that the Junkers plant at Dessau convert the Ju-52/3m to a bomber configuration (the g3e), and Junkers engineers had installed vertical magazines in its lower cargo bay to accommodate 3,306 pounds of explosives. The makeshift bombers operated with crews of five handling the positions of pilot, co-pilot, radio operator, dorsal gunner, and bombardier/ventral gunner.

Early in the conflict, the Ju-52/3ms played a key role in transporting 13,900 Moorish troops and their heavy weapons to Spain. Lt. Col. Rudolf Moreau established the first official bomber squadron numbering 10 Ju-52/3mg3es in November 1936 to support the Nationalist ground forces. During the course of the conflict, the Moreau squadron dropped more than 6,000 tons of bombs on enemy positions and enemy-held territory. However, the Ju-52/3m’s bomber days were numbered not only because of its lack of speed and maneuverability but because it could not accommodate the horizontal bomb racks that were being installed on newer medium-range bombers in production. As the fighter threat grew more severe in the following months, the Ju-52/3mg3e’s were replaced with more advanced bombers, such as the Dornier Do-17 and the Heinkel He-111. While the Spanish Civil War raged on into its third year, the Ju-52/3ms functioning as bombers were converted back to transports.

Paratroopers in the North: Ju-52s in Operation Weserübung

The invasion of Denmark and Norway on April 9, 1940, known as Operation Weserübung, heralded the use of Ju-52/3ms to deliver paratroopers and air landing forces to the battlefield. During Weserübung, the transports performed a number of key roles, including dropping paratroopers, ferrying air landing troops to captured airfields, and delivering heavy weapons and supplies to paratroopers and other ground forces.

Weserübung involved the first paratrooper attacks in military history. On the first day of the invasion, the paratroopers seized the Vordingborg Bridge linking Copenhagen with its ferry terminal and two airfields at Aalborg in Denmark. The Ju-52/3ms also dropped paratroopers at three key airfields in southern Norway at the cities of Oslo, Stavanger, and Kristiansand.

As the battle progressed over the following days, the Ju-52/3ms played a crucial role delivering weapons and supplies to the German troops fighting Allied forces at the North Sea port of Narvik. A particularly daring mission involved the ferrying of a fully equipped mountain battery to a frozen lake 15 miles north of Narvik with little chance of their returning due to the extreme conditions. The planes took off from Hamburg, refueled at Oslo, and proceeded to their destination. They remained on the frozen lake until they sank in the spring thaw. The lost planes, however, were only a small part of the Ju-52/3m losses incurred during the overall operation. The Luftwaffe counted about 150 transports destroyed or damaged beyond repair by the end of the affair. It was a taste of the heavy losses to come in campaigns ahead.

The Ju-52/3m had various types of landing gear to adapt to both snow and water. During the fighting in Norway, wheeled landing gear was replaced with floats to enable the planes to land in that country’s numerous fjords. Similarly, skis replaced wheels when the Ju-52s had to land in the vast expanses of Russia during the cold months, whether at the front line or in rear areas. In addition, the service crews eventually removed the tear-shaped wheel covers from most planes serving on the Eastern Front when they discovered that mud collected quickly inside them.

Other modifications were made to accommodate paratroopers and to provide better protection against enemy fighter aircraft that attacked the Ju-52/3ms like sharks feeding on fish. The Ju-52 g4f included a reinforced cargo compartment floor, side, and loading doors. It could carry 12 to 13 fully equipped paratroopers and up to 18 air landing troops. In 1941, these planes were upgunned when the dorsal 7.9mm MG 15 was replaced with the 13mm MG 131. While the heavier gun afforded protection against attacks from the rear, the aircraft remained vulnerable to frontal attacks. For this reason, an additional MG 15 was installed in the roof of the cockpit and manned by the radioman. By this time the ventral dustbin had become impractical and was removed from many of the transports.

167 Aircraft Destroyed

The Ju-52 also was employed as a minesweeper. At the start of the war, German scientists discovered that mines laid by British aircraft along German-held coastline could be detonated by a magnetic field. Thus, the Ju-52 g4f was outfitted with an enormous horizontal ring on the underside and wings. An electrical charge was fed into the aluminum ring by a battery. Since the mines were equipped with delayed fuses of seven seconds, the mines detonated about 200 to 300 meters behind the aircraft flying at low level. The minesweeper version was first deployed in 1940 along the Dutch coast and saw its greatest use along the coastline of occupied France.

The Junkers engineers designed two improved versions of the Ju-52 that were intended as replacements for the original design but never made it to full production. The Ju-252 had three Jumo 211 engines, was armed with the MG 131 dorsal gun placed directly behind the cockpit, and had nearly three times the load-carrying capacity of the Ju-52. It did not have the Ju-52’s corrugated exterior, and it came equipped with a hydraulic rear loading ramp to make loading and unloading of weapons and equipment easier. After its maiden voyage in October 1941, roughly 15 were completed. The following year production began on the Ju-352. This variation was constructed of alternate materials, due to a shortage of metal, and featured three BMW-Bramo engines. The 352 made its maiden flight on October 1, 1943.

Following Weserübung, the Ju-52s had little time to be repaired and reoutfitted before they were delivering paratroopers to key objectives in Belgium and Holland the following month. About 430 Ju-52s participated in the operation. A group of 40 were assigned to tow DFS 230 gliders carrying assault troops who captured the Belgian fortress of Eben Emael, while the remaining 390 carried paratroopers and air landing troops to seize bridges and other objectives in Fortress Holland where the cities of Amsterdam and Rotterdam were located. The heavy attrition among the Luftwaffe’s Ju-52 fleet continued in the Western Campaign with 167 of the aircraft involved destroyed.

Ju-52s in the Mediterranean Theater

An even larger, more significant airborne invasion took place almost exactly one year later. After the fall of mainland Greece, Hitler launched Operation Mercury to capture the island of Crete and deny the Allies the use of its three airfields. More than 500 Ju-52/3ms dropped the four parachute regiments of the 7th Air Division onto the island and also ferried the 5th Mountain Division to Maleme airfield, which was captured on the second day. It was the first battle conducted entirely by paratroops and air landing forces.

During the first day’s assault, the Ju-52/3ms not only towed 75 gliders carrying the 7th Division’s elite assault regiment but also delivered three regiments in two waves to seven separate objectives on the island’s north coast. It was a costly battle in lives and equipment, with the Luftwaffe losing 271 of the 502 Ju-52/3m aircraft assigned to the operation. The thin-skinned fuselages and wings proved vulnerable to heavy antiaircraft fire from British and Commonwealth forces in strong positions. As a result of this experience and subsequent experiences on the Eastern Front, engineers made the air frames of a number of Ju-52s bulletproof to protect the flight crews.

More than 50 Ju-52/3ms had been deployed in December 1940 to Foggia, Italy, to support Italian operations in Albania and North Africa. They transported 1,665 Italian soldiers to Albania and evacuated more than 8,730 wounded Italians back to Italy over the next five months until Greece fell in April. Three months later, General Erwin Rommel arrived in North Africa at the port of Tripoli, Libya, with his Afrika Korps. Ju-52s were an integral part of supply operations from the time Rommel landed until the Germans evacuated the last of their forces from Tunisia in May 1943.

After United States forces invaded Morocco and Algeria in November 1942, U.S. fighters regularly intercepted Ju-52s engaged in the evacuation of forces from North Africa to Sicily. In a stunning aerial battle on April 5, 1943, U.S. Lockheed P-38 Lightnings jumped an armada of more than 50 Ju-52s in the early morning off the western coast of Sicily. The U.S. fighters shot 14 out of the sky and damaged 65 parked on Sicilian airstrips. Another Allied victory occurred on April 18 when U.S. fighter aircraft pounced on an armada of 65 Ju-52s moving men and materiél and shot down 24 planes. Nevertheless, the Ju-52s left behind an impressive legacy, having flown 8,388 soldiers and ferried 5,040 tons of supplies to North Africa to support Rommel’s campaigns.

Keeping the Eastern Front Supplied

The Junkers factories increased production of Ju-52/3ms from 388 in 1940 to 502 and 503 in 1941 and 1942, respectively. The increased production was necessary to literally feed the hungry stomachs of Germans soldiers on the Eastern Front. Five of the six air transport groups were shifted to occupied territories in the East to support troops operating hundreds of miles from the German frontier where partisans frequently disrupted supply lines and retreating Soviet forces practiced a scorched earth policy.

When their blitzkrieg ground to a halt a short distance from Moscow during the winter of 1941, large numbers of Germans were cut off in subsequent Soviet counterattacks. The only way they could receive supplies was by Ju-52s either landing on airstrips inside the pockets or dropping supplies from the air. The largest pocket resulting from the Soviet winter offensive of 1941-1942 resulted in the creation of the Demyansk pocket where nearly 100,000 German soldiers were surrounded by the Soviet Eleventh and Thirty-Fourth Armies. The forces trapped inside the Demyansk cauldron required about 300 tons of supplies per day. About 75 Ju-52s flew 33,000 sorties into the pocket, which existed from February 8 to April 21, 1942.

While the Ju-52s rose to the occasion in those situations, they would not be able to meet the impossible demands of supplying the German Sixth Army when it was surrounded at Stalingrad by four Soviet army groups in mid-November 1942. The success at Demyansk made Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring and others believe it would be possible to supply the troops until they could be relieved. The daily requirement was 600 tons, which was twice that of the Demyansk pocket. This would require 300 Ju-52s. Even though all air transport resources on the Eastern Front were brought to bear, the number could not be mustered, and the actual number available steadily declined through battle losses. The greatest amount of supplies ever delivered on a given day was 289 tons, while the average was around 90 tons.

When the last airfield (Pitomnik) inside the pocket fell to the Soviets in mid-January 1943, the transports resorted to dropping supplies from the air. By the time the Sixth Army surrendered on February 2, the Luftwaffe had lost the equivalent of 266 Ju-52s in a futile effort to supply the beleaguered forces.

Like the breadwinner who is devoted to feeding his family, the Ju-52 would supply troops with food and ammunition in other major pockets until the end of the war, including the Crimean peninsula in 1944-1945, Budapest, and Breslau. Of the 2,822 Ju-52/3ms produced from 1939 to 1944, only 190 were left in service when Berlin fell on May 7.

Although the Ju-52/3m was clearly inferior in terms of flight speed and payload to the U.S. Douglas DC-3 Dakota/C-47 Skytrain, it has earned accolades from military aviation experts for its versatile performance during the war. There is little doubt that it will be associated for a long time with both the highs and lows of the Third Reich in World War II.

Vienna, Virginia, freelance writer William Welsh has written articles on conflicts from the Middle Ages to World War II. He is also a regular contributor to Sovereign Media’s Military Heritage magazine.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments