By Robert Barr Smith

In the spring of 1918, World War I was well into its fourth year, and still the armies struggled and died in the glutinous mud of Flanders. Imperial Russia, exhausted and ravaged by revolution, was out of the war. Germany shifted troops to the west, throwing her newly arrived sturmtruppen against the virtually exhausted French and British. The Allies’ lines had bent, but they had not broken. And now the Americans were arriving to help, sending hundreds of thousands of fresh, eager troops to help end the brutal stalemate on the Western Front.

At sea, in spite of the Allied navies’ convoy system, the German U-boat menace continued, a constant danger to ships carrying fresh troops and munitions for the hungry guns in France. The U-boats were slipping through with impunity to infest the North Atlantic and the waters west of Great Britain and Ireland. They had to be stopped. The Dover Patrol, a motley collection of destroyers, trawlers, drifters, monitors, and motorboats, was assembled to stop the infiltration of German submarines through the English Channel. It was augmented by floating minefields and submerged nets, but German U-boats still managed to slip through the defenses to haunt shipping lanes in the Atlantic and the Irish Sea.

Documents captured from a German boat sunk off Ireland told the reason why. The U-boat skippers had strict orders to pass the Channel in darkness and on the surface, diving deep at any chance of discovery. For all their hard work and dedication, the little craft of the Dover Patrol seldom sighted the almost invisible German boats before being spotted themselves—a U-boat running awash was a tiny target in the gloom of night. Those submarines that traveled the much longer route north around Scotland were ordered to let themselves be seen to convince the British that the Germans were sending most of their boats to sea that way.

Not all of the Unterseebooten were coming from Germany, however. Many were based directly across the Channel in occupied Belgium, particularly at the ancient city of Bruges. From Bruges, U-boats and squadrons of torpedo boats wended their way eight miles to sea through an intricate canal system that emptied into the Channel at a tiny port called Zeebrugge. The Bruges harbor could hold some 30 submarines and even more torpedo boats, which could also put to sea through the more difficult canal route to the port of Ostend. Since they were closer to British shipping lanes, the boats based in Belgium had a much greater radius of action than those sailing from Germany, and their crews remained far fresher while serving in their operational areas.

A Daring Plan to Block Zeebrugge

But that was about to change. Three days after Christmas 1917, a new and dynamic leader assumed command of the Dover Patrol. Sir Roger Keyes was a slim, tough rear admiral who had sailed under the white ensign since he was a boy. Keyes had served in the Boxer Rebellion, winning early promotion, and had been at the Dardanelles as well, acting as chief of staff of the Mediterranean Fleet. He was a hardened old sea dog, indeed, in spite of his soft-spoken manner, and he immediately set about making changes, removing most of the anti-submarine nets and extending the minefields to new areas and depths. Keyes stepped up night patrols, and his forces began to make much greater use of searchlights and a white flare of blinding brilliance developed by Wing Commander Frank A. Brock, scion of a British fireworks manufacturer. Within a month, five U-boats had been destroyed by the Patrol. One was sunk by depth charges; the others, forced under by Brock’s brilliant flares, fatally dived into British minefields.

Keyes turned his attention to Bruges and its ports, Zeebrugge and Ostend, those nests of vipers preying on British shipping. Plans to deal with both ports had been considered before, but they had usually involved shelling with heavy artillery. That approach had been tried and found wanting. Dover monitors had unsuccessfully hurled 15-inch shells at Zeebrugge’s lock gates, an effort much like lobbing a golfball at an unseen hole 100 yards away. Another somewhat surrealistic scheme involved putting a large landing force ashore then setting up an 18-inch gun inside the Palace Hotel in Westende village to bombard Zeebrugge. Understandably, that pipe dream failed to get much of a hearing.

Keyes’s plan, though equally daring, was also a good deal more practical. The Zeebrugge lock gates were half a mile up the canal, too far to send a ship to ram them. But the channel leading to the gates and on to Bruges might be closed permanently by blockships placed during a well-organized commando raid. And even if the sunken blockships in the canal entrance did not entirely obstruct the canal by themselves, drifting silt would soon pile up against their hulls to clog the channel. Still, the difficulties were legion. Zeebrugge is 65 miles from the English coast at its nearest point, a long way to sail without being detected. In addition to the guns at Zeebrugge itself, the coast on both sides of the harbor mounted more than 200 artillery pieces. Some were as large as 15 inches, shooting projectiles that stood six feet high and weighed almost a ton.

A Well Protected Harbor

The Belgian coast is a convoluted maze of sandbanks and twisting channels; the depth and direction of its waterways are constantly being changed by a powerful wave flow running 15 feet high between high and low tides. The Germans had long since removed all channel buoys, and no one could say precisely where the shoals lay, how shallow they actually were, or how far out they extended. To make the blocking expedition even more difficult, the ship channel leading to Bruges from Zeebrugge harbor was only 116 yards wide. At the best of times, a ship drawing more than 12 feet could enter the channel only by staying precisely in its center.

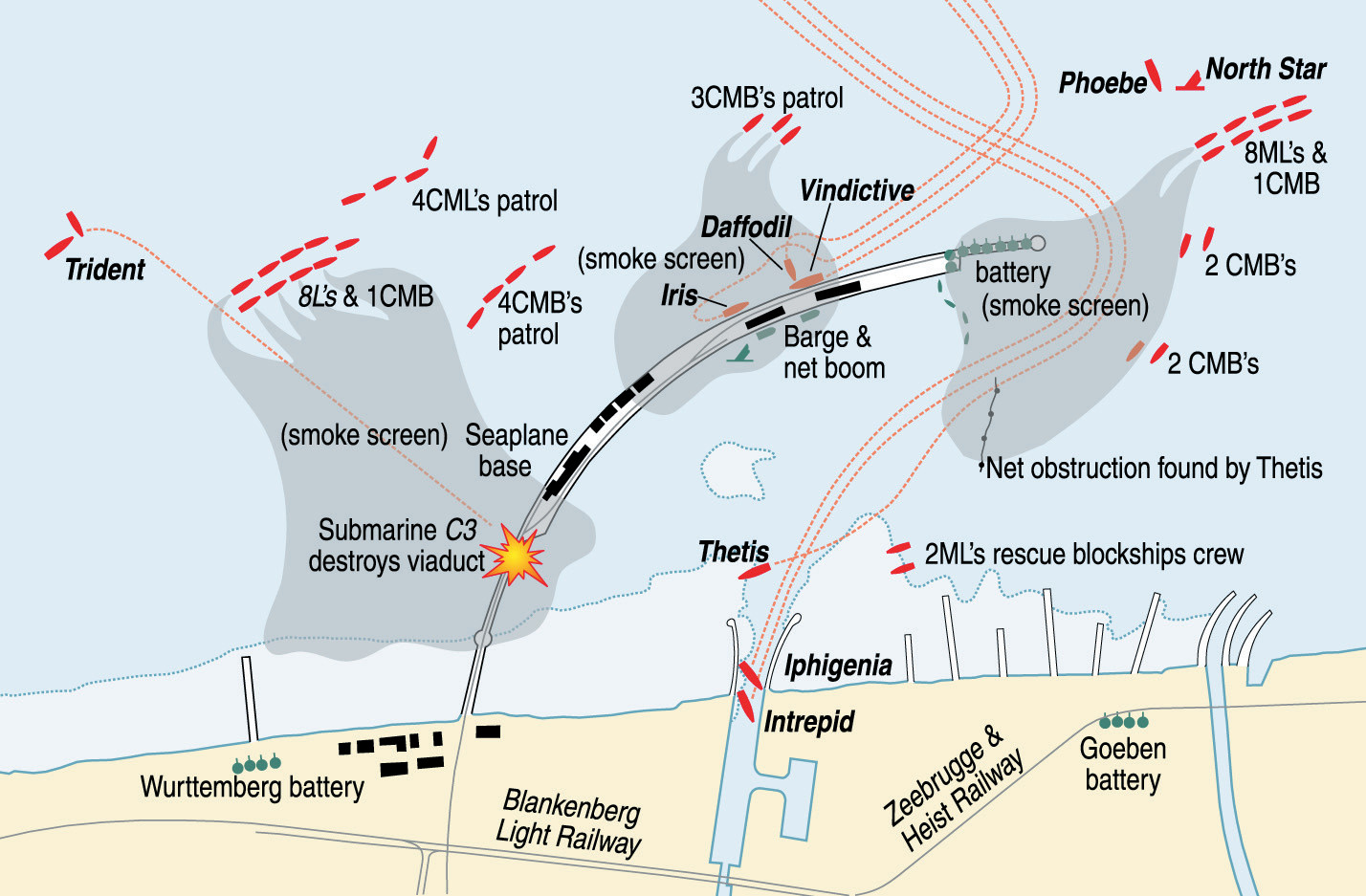

The harbor itself bristled with artillery. But the German guns, many firing at point-blank range, were not the only problems. The canal mouth lay well behind a monstrous mole, or breakwater, which created an artificial harbor surrounding the canal entrance. The mole began half a mile west of the canal mouth and then curved northeast for another mile and a half. The whole channel required constant dredging because of the accumulation of silt brought in by the tidal current. Next to the shore, the mole began with a 300-yard causeway leading to a viaduct or open pier made of steel girders, also 300 yards long. The construction of this part of the mole created a sort of sluice effect, enabling the western tidal current to wash the inside of the mole clear of silt. Both sections of the mole were connected to shore by a shared road.

Next came the breakwater itself, about 80 yards wide and more than a mile long. The road continued down it, and on the seaward side a tall parapet towered 30 feet above the sea, even at high tide. The last section of the mole was a narrow 300-foot pier ending in a lighthouse. This section also had a parapet facing the sea, and mounted at least six artillery pieces that could tear apart at point-blank range any blockship attempting to sail past them into the canal. To make matters worse, a barge boom obstructed the channel off the tip of the pier. This obstruction was made of four Rhine River barges cabled together and filled with stones. Another boom, made of heavy nets supported by buoys, was put in place to foul the screws of any ship that attempted to cross.

Behind the main part of the mole was a battery of heavy 5.9-inch guns, which could also cover the entrance to the channel. Worse still, the mole was infested with concrete emplacements for machine guns and antiaircraft guns, infantry positions, and a wilderness of barbed wire. The place was garrisoned by more than 1,000 German defenders, and naval destroyers were normally moored inside the mole, where their guns could also sweep the channel entrance.

A Motley Fleet

Still, Keyes thought his plan could work. The trick was to attack the mole first, putting ashore Royal Marine and Royal Navy landing parties to silence the guns. Even if the guns could not be knocked out, the landing parties might raise so much havoc that the garrison would not notice the blockships until it was too late and they were already in the canal entrance. Keyes requisitioned six obsolete light cruisers, originally intended for the scuttling yard, but now reprieved to end their careers in a much grander style. Thetis, Iphigenia, and Intrepid would be the Zeebrugge blockships. Proud, old Vindictive would have another role to play— she would carry most of the Marines and Bluejackets who would storm the mole.

The extensive modifications to Vindictive began immediately. Be-cause of the enormous height of the mole on its seaward side, some way had to be devised to get the landing parties onto the top of the mole quickly and in condition to fight. British shipfitters equipped Vindictive with 18 narrow ramps that were raised by block-and-tackle like drawbridges, ready to be dropped onto the top of the mole and mounted by the landing parties. The bases of these ramps, or “brows,” were hinged to a false deck built the whole length of Vindictive’s port side. The Navy also provided grapnels to secure both Vindictive and the gangways to the mole. The false deck would bring the landing parties closer to the top of the parapet on the mole, but they would still be five to eight feet below it when they started up the bucking, swaying gangways. The Marines and Bluejackets would also have to carry scaling ladders to get down the 16-foot drop from the parapet to the road behind it on the mole.

Vindictive got added weaponry. Two 7.5-inch howitzers and an 11-inch howitzer were mounted on her decks, providing high-angle fire over the mole. Six Lewis light machine guns and three quick-firing cannon were installed on her fighting deck, which towered above the mole. Ten more Lewis guns were placed on the false deck, and Stokes mortars were scattered everywhere there was space. Sandbagged huts were built fore and aft, each one enclosing a flamethrower. Lastly, all the cruiser’s exposed positions were covered with sandbags and mattresses, and her foremast was cut away and lashed across her stern to prevent her port propeller from banging against the mole.

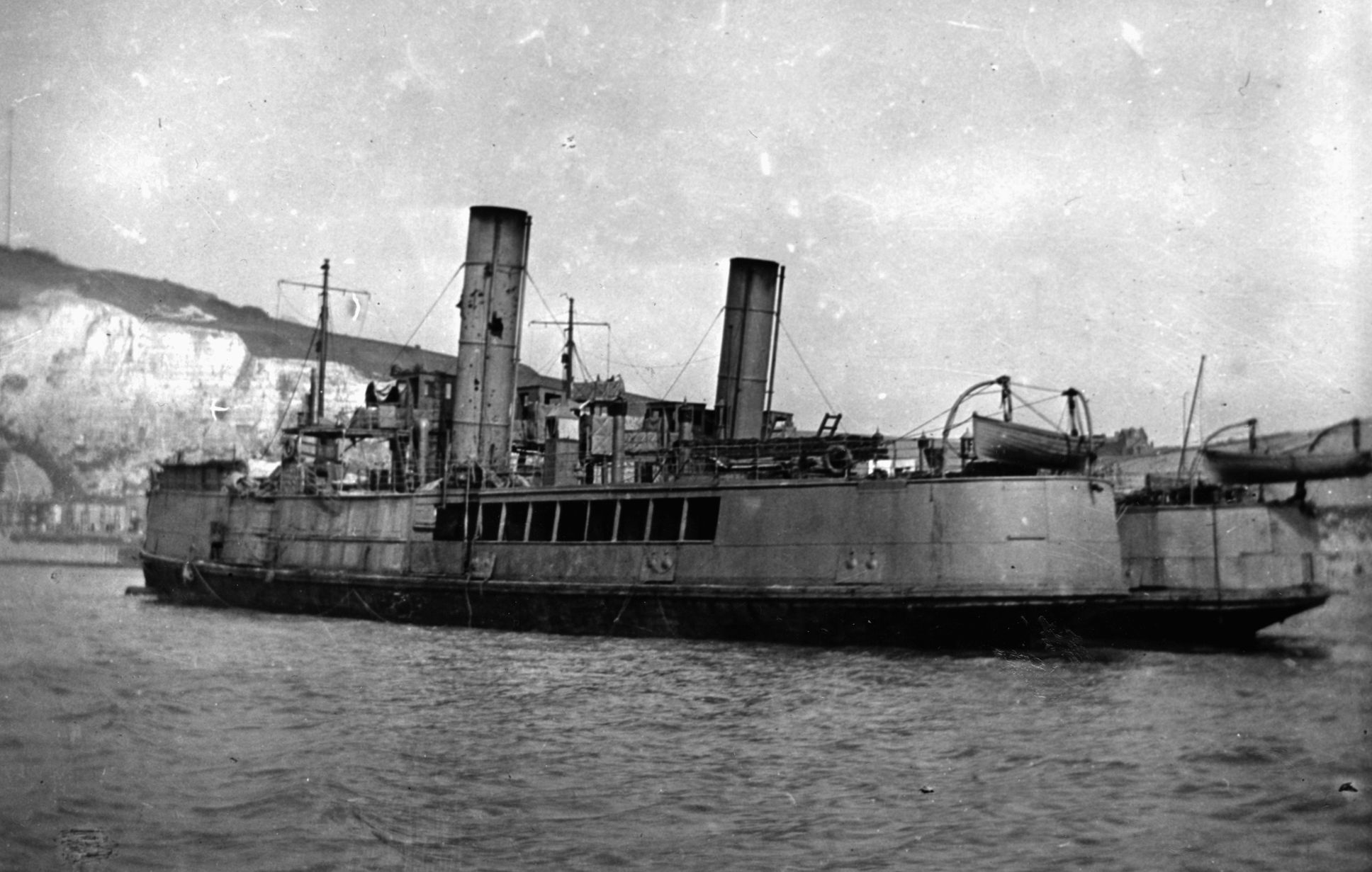

Because Vindictive had a deep draft, there was always the chance she would strike a mine in the uncharted shallows off Zeebrugge. To provide some additional shallow-draft support, Keyes acquired two most unlikely warships, the Merseyside ferryboats Iris II and Daffodil. Civilians to this point, they had spent their lives placidly carrying the people of Liverpool about their peaceable errands. Now they were going to war. For all their squatty, benign appearance, Iris II and Daffodil were stable and tough, with double hulls. They would hold lots of people once their inside fittings had been torn out and some armor bolted on. They, too, were sandbagged and mattressed and fitted with smoke-making equipment, grapnels and scaling ladders for climbing the steep parapet of the mole.

Then there were the submarines. Old “C”-class submarines C1 and C3 were in fact floating bombs. Each carried a much-reduced crew of six and some five tons of amatol. Their mission was to work westward around the curve of the mole to the open pier, wedge themselves beneath it, and light the fuses. If all went well, the steel girders of the pier would disappear in a flash of brilliant white light, leaving the Germans on the mole without reinforcements. With luck, the crews of the submarines would be taken off by small motorboats before the amatol went up.

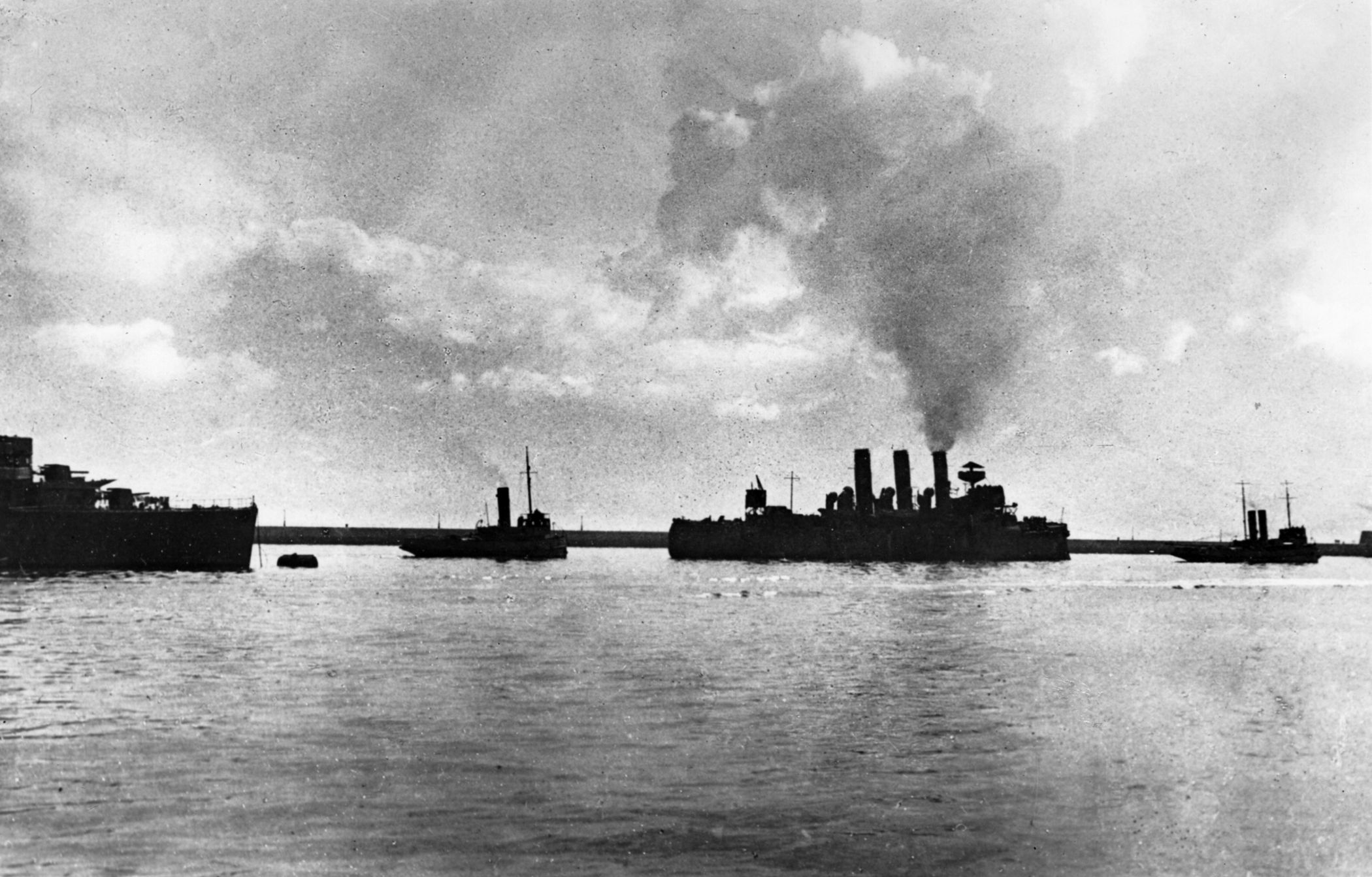

162 Vessels

Altogether, 162 vessels were found to participate in the raid. Besides the cruiser blockships Thetis, Intrepid, and Iphigenia, the troop carrier Vindictive, the submarines, and the ferryboats, there were two heavy-gun monitors for shore bombardment, a covey of destroyers to cover the operation, and a whole crowd of small, quick motorboats for rescue work. Other motorboats would get close to shore to make chemical smoke with special smoke machines designed by Brock, then enter the harbor itself to torpedo anything that happened to be moored there. A number of Handley-Page heavy bombers were added to the mix as well. They were to raid Zeebrugge during the attack, creating even more confusion and distraction for the garrison.

The blockships carried extra crews to man each ship on her way across the English-Channel, giving some extra rest to the crew that would actually take the cruiser into the Zeebrugge channel. Vindictive, Iris II, and Daffodil also had two complete crews. One would remain on board to take the ship home in the event that most or all of the first crew became casualties or did not make it back from the mole. The blockships were each given an artfully placed cargo of concrete. The concrete would make them very hard to move once they were sunk in place. If placed correctly in the hulls, it would render the ships almost impervious to the salvaging expedient of cutting up a ship and raising its pieces. The blockships also retained their armament. Once they reached the harbor, they would go in shooting.

The attackers would have to go in as close to high tide as possible to give the landing parties their best chance to climb onto the mole and the blockships the maximum depth of water beneath their keels as they drove into the narrow channel. The attack would have to be mounted on a dark night in reasonably calm weather, late enough for most of the run-in to Zeebrugge to be made under the cover of darkness, but still early enough to allow the task force to clear the Belgian coast before dawn. Only four or five nights fit all these criteria. To augment the cover of darkness, the attackers needed an onshore breeze to keep the smoke in the Germans’ faces, adding one more requirement to the Navy’s long list. The ships’ progress would be controlled by a strict timetable, and the ships of the main force would be guided by buoys laid in the Channel by small boats. Further position marking would be done by floating calcium flares, also developed by Brock.

The Men of the Mission

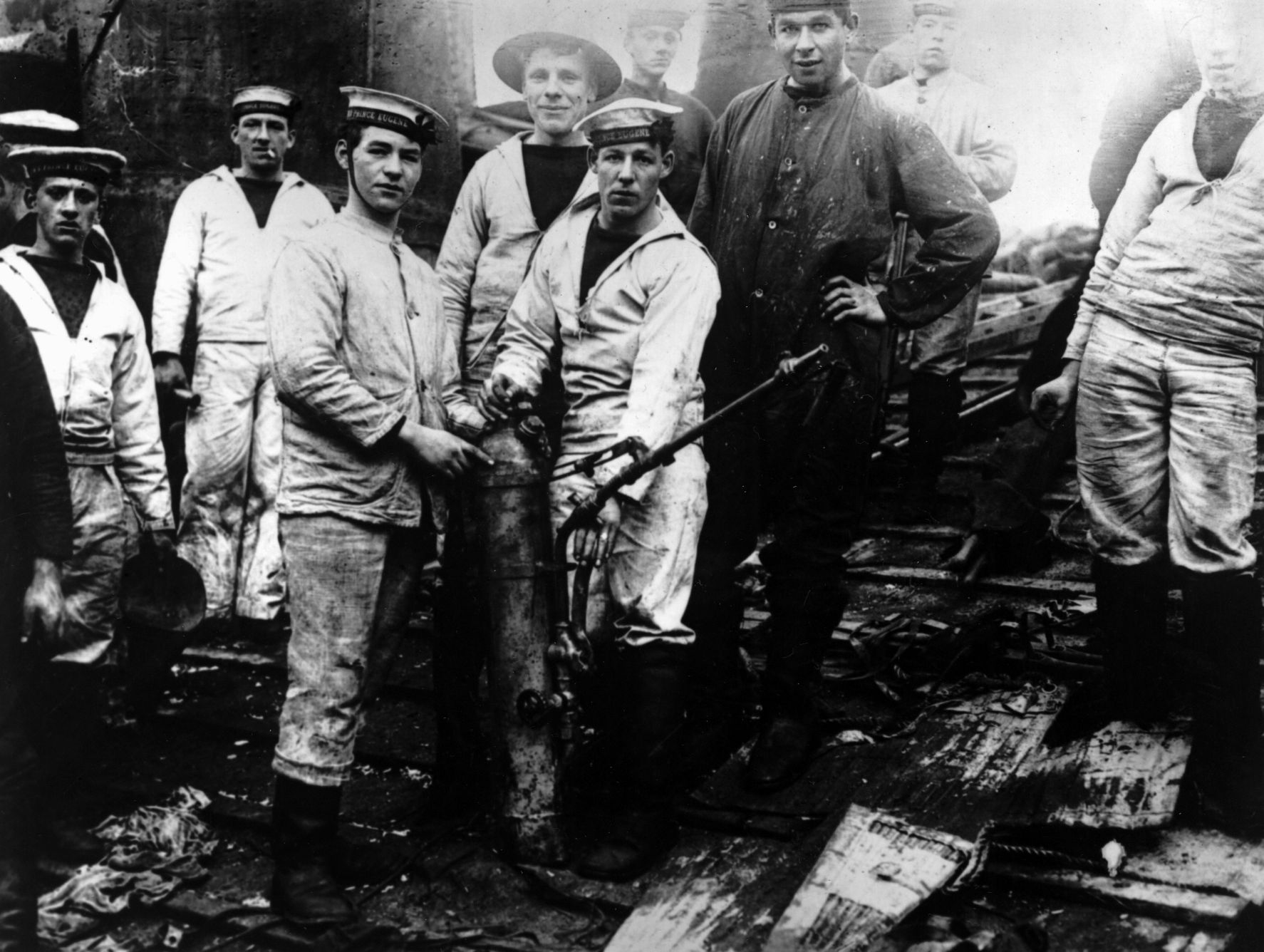

The men for the mission were easy to find. Even though Britain was terribly tired and her manpower reservoir was running low, both officers and enlisted men responded in droves. One of Keyes’s most painful duties was turning away the dozens of officers who pleaded with him to go along in any capacity. After the flotilla sailed from England and it was too late to turn back, a number of stowaways began to materialize from nooks and crannies on the various ships, and every man of the blockships’ extra crews volunteered to remain on board all the way into Zeebrugge. One Navy crew, discovering that it was not slated to go all the way to the objective, came perilously close to mutiny. The crew spokesman put it plainly to a sympathetic officer: “Well, sir, me and my mates understands as how some of the crew have got to leave the ship on the way across to Zeebruggy. The Jaunty [the master-at-arms] says it is us lot and we ain’t a-goin’ to leave.” The officer listened to their complaint and decided on the spot to take along an extra gun crew. The men drew lots for places on the gun, but the whole crew wound up going to Zeebrugge when their pickup boat broke down. All the rebellious volunteers returned safely.

No one wanted to be left out of the mission, and volunteers came from everywhere. Cooks and other support personnel raised their hands, and more came from the civilian employees of the company that ran the sailors’ canteen. Some of these volunteers were taken along to help with the wounded. One officer received an irate deputation from the engine room. Their spokesman addressed him: “Me and my mates, sir, understand that we ain’t allowed to leave the stokehold and have a go at the Hun.” That was so, said the officer. The stoker tried another tack: “Well, sir, we wants to know if we may guard the prisoners in the stokehold.” The request was denied, as Captain Alfred Carpenter of Vindictive later wrote, because “it spelt too much discomfort for the prisoners.”

A battalion of Royal Marines formed at Dover and began to rehearse the operation on King’s Down, outside the town. Dover residents wondered at the sight of hundreds of Marines going through strange evolutions, day and night, amid strips of canvas laid out on the hillside. Nobody knew that the canvas represented the fortifications on the mole, including the Marines, who thought they were getting ready for an attack somewhere behind enemy lines in France. In addition to the Marines, there was to be a Royal Navy landing force of 200 Bluejackets, plus 50 more sailors who were expert in demolitions work. The naval force was commanded by Navy Captain Henry Stuart Halahan, who would sail aboard Vindictive. Carpenter would remain in command of Vindictive and direct Daffodil as well. Keyes promoted Carpenter to acting captain on the spot before the raid, and his confidence would be fully justified.

By the end of March, the force was in readiness. All that remained was the right combination of moon and weather, wind and tide. The landing parties were trained to a fine edge and jammed into the ships. Waiting was agony. Twice the signal to go was given and the motley fleet set sail. Twice conditions worsened and the ships had to return home without firing a shot—but also without being discovered by the Germans. At last the day came. It was April 22, fittingly the eve of the feast day of St. George, patron saint of England. That afternoon the various contingents of the force began to put to sea, and by 7:30 that evening the flotilla was assembled and turning for the Belgian coast. As night settled down, Keyes, in the destroyerWarwick, signaled to the fleet the ancient battle cry: “St. George for England!” Carpenter signaled back from Vindictive: “May we give the dragon’s tail a damned good twist.” The operation was on.

The Zeebrugge Raid

A little after midnight, the ships reached the buoy at which the blockships were to drop off the crews that had brought them from England and sail on with the crews that would take them into the mouth of the canal. The small boat assigned to remove the spare crew from Intrepid had broken down, however, and her spare crew, to its intense delight, continued on to the objective. Some of the extra men on Thetis and Iphigenia hid away and missed the launch that lifted off the extra crews. It began to drizzle. The rain helped hide the little flotilla, cruising in a thick screen of Brock’s smoke, but it also prevented the planned diversionary strike by British bombers. The ships sailed on in silence; the Belgian coast remained dark.

Just before midnight, with Vindictive only a quarter-mile from the mole, the north wind shifted and the friendly cloud cover was blown away just when it was needed most. Instantly the sea around the ships churned with German shell bursts. Carpenter grimly called for full speed, steering the shortest course for the stone mass looming before him. German shells tore into the ungainly old cruiser, destroying the forward howitzer, killing men among both crew and landing party and turning her upper works into junk. The ship bored in, flames shooting from gaping holes in her funnels, her deck and superstructure ablaze with enemy shell hits and the muzzle flashes of her own guns. Carpenter swung Vindictive hard against the mole, where at least her hull was protected from the torrent of fire out of Zeebrugge. But she was a quarter of a mile west of her intended landing area, and one anchor was jammed in place. Carpenter dropped the other hook and ran his ship astern as far as he could, but Vindictive was still too far from the mole.

Out of the night loomed the chubby Mersey ferryboats, Iris II and Daffodil, already taking hits from German guns, but chugging steadily in toward the mole. Daffodil’s captain, Lieutenant Harold G. Campbell, wounded and half-blind, nevertheless saw Carpenter’s predicament and neatly swung his little ship bow-first into Vindictive’s starboard side, pushing the cruiser hard against the mole. Vindictive dropped her gangways onto the top of the mole. Captain Edward Bamford led Bluejackets and Marines up the gangways that still were passable—only two of 18 were still undamaged—running across the wildly bouncing planks to reach the parapet of the mole. The men ran into a storm of fire and began taking casualties immediately.

Just to the west of Vindictive, Iris II pulled up to the mole to land her storming parties. The ferry was tossing badly, and one of the grapnels meant to hold her to the mole could not be fixed as the little ship rolled and pitched. One young officer, Lieutenant Claude Hawkings, had already tried to set a grapnel, fighting with his revolver until he was killed. Lt. Cmdr. George Bradford, commanding the landing force, now grabbed the grapnel and climbed a derrick that stuck out over the mole. As the ferry rolled and the derrick crashed against the mole, he timed his jump and leaped to the parapet, where he got the grapnel in position to hold Iris II firmly against the mole. Almost immediately, Bradford was hit by German fire and fell between Iris II and the mole, never to be seen again. It was his birthday.

Bradford’s gallantry would win him one of eight Victoria Crosses awarded that day. Tragically, Bradford was one of four warrior-brothers who fought in World War I. His brother Roland, a battalion commander with the Durham Light Infantry, also won the VC before being killed at Cambrai as a 25-year-old brigadier general. A third brother, James, winner of the Military Cross, was killed at Arras in 1917. Only one of the brothers, himself the winner of a DSO, returned to England.

Assault on the Mole

As the landing parties swarmed up the gangways toward the mole parapet, they were covered by steady fire from the cruiser’s foretop. The Marine gunners stationed there raked the infantry positions on the mole and blasted the upper works and gun positions of two German destroyers moored inside the mole. On board Vindictive, Carpenter walked the ravaged decks, littered with dead and wounded, talking calmly and encouragingly to his men.

Inside the harbor, British motorboats raced through the hail of steel, dropping smoke floats within a few yards of the German batteries. One motorboat torpedoed a German vessel that was attempting to leave port; another sent a torpedo into a destroyer moored inside the mole. Others pushed into the harbor to fire mortars at targets around the inside curve of the mole, closing the range to as little as 50 yards. Halahan was killed in the opening moments, as German shells slammed into Vindictive. Near him fell Royal Marine Lt. Col. Bertram Elliott, commander of the landing parties, and Major Alexander Cordner, his second in command. Carpenter, miraculously untouched, went about keeping his battered ship hard against the mole as missiles of all sizes crashed and whined around him. Both flamethrowers were out of action, one from a break in the fuel line leading to it, the other from a smashed ignition device. Nearly every man around the conning tower was down, either dead or wounded.

Through the chaos, the leaders maintained the wonderful calm long bred in Royal Navy officers. Carpenter found Lieutenant E. Hilton Young chomping on a huge cigar as he supervised the firing of Vindictive’s forward guns. Young nodded to his bandaged arm and cheerfully remarked that he had “got one in the arm.” He had indeed. His arm would be amputated as a result of the wound, but the smiling officer would survive. At the head of one of the ladders lay Lieutenant H.T.C. Walker, his arm torn off during the assault on the mole. Seeing Carpenter he waved his remaining hand and called out good luck to his commander. Walker, too, would survive.

Meanwhile, down on the mole, Lt. Cmdr. Arthur Harrison led a storming party in spite of the pain of a broken jaw suffered when a shell fragment knocked him temporarily unconscious on Vindictive. Running into the teeth of German machine-gun fire, Harrison died on the mole, despite the efforts of his men to pull him to safety. His courage and example would win him a posthumous Victoria Cross. A VC would also go to Able Seaman Albert McKenzie, who followed Harrison down the mole, raking the German defenders with his Lewis gun. Badly wounded, McKenzie would survive.

Through the fire and smoke strode a Church of England chaplain named Peshall, who, like Harrison, once had been an international rugby star for England. His comfort was the last kindness many fatally injured men would know. Throughout the night he went calmly back and forth across the rickety, shell-swept bridges between Vindictive and the mole, carrying one wounded man after another away from the German fire. On Vindictive, a petty officer jumped into the flames of burning boxes of mortar rounds, ordering others to take cover while he stamped out the fire. At that moment, two lucky German shells struck Vindictive’s foretop, killing or wounding every man there. Only one Marine, Sergeant Norman Finch, could move enough to drag himself to an undamaged Lewis gun and open fire again on the Germans. He fired pan after pan of ammunition, raking the mole defenses, until another shell struck the top, wounding him again. Even then, Finch found the strength to drag another badly wounded man from the foretop to safety before passing out.

Finch’s heroism would earn him the Victoria Cross, but now that he was down there was no suppressive fire on the German defenses, and the landing parties were taking terrible casualties as they grenaded their way down the mole. Their losses were ghastly, including pyrotechnics expert Frank Brock, who died somewhere on the mole that flaming night. Wounded men went on, pushing toward the mole batteries until they, too, were killed. But the selfless work of the landing parties was accomplishing what it was meant to do. The Germans had no eyes for anything but the persistent, pestilential Englishmen on the mole, and thus missed the approach of submarine C3 entirely as she slid in from the west.

Five Tons of Amatol

Except for a couple of errant shells, there was no opposition until C3 was close enough to see the outline of the steel girders ahead. Suddenly framed in the beams of three German searchlights, C3’s skipper, young Lieutenant Richard Sandford, sent her straight for the pier. She struck the latticework of girders flat out, wedging herself between them up to the conning tower and raising her bow two feet out of the water. Twelve feet overhead was the roadway to the mole. Sandford coolly lit his fuses and jumped down onto his hull and into a little motor skiff brought along for the purpose. He was not pleased to find that the propeller would not operate, but he and his men began to row, pulling hard against a powerful current that threatened to push them back against the monstrous bomb that was now C3.

To make matters worse, the little boat began to take a hail of German automatic weapons fire from almost point-blank range. Sandford was badly wounded, and two of his men were also down. Still they rowed, hoping the automatic bilge pump could keep up with the cold channel water rushing into the skiff through various bullet holes. As they began to make a little headway, the German fire increased, and things began to look hopeless for the little crew of C3. Then C3 blew up. With a brilliant flash and a colossal roar, five tons of amatol shattered the night, and the iron girders disappeared, along with the unlucky lead elements of a German bicycle unit peddling madly out to reinforce the garrison on the mole. As the trailing ranks of the bicycle unit skidded and braked and fell into the gaping hole in the pier, a seaman onboard Iphigenia watched a German soldier and his bicycle fly through the air over the mole.

Scuttling the Blockships

The blockships were coming through at last, led by Thetis. They emerged from the remains of the smoke right on track, headed straight in toward the channel. Thanks to the sacrifice of the landing parties and C3’s amatol, the blockships were well on their way to their objective before the Germans reacted. When the enemy fire came, it was devastating, particularly the point-blank salvos from the mole battery. As Thetis boiled into the gap between the barge-boom and the net, she was struck again and again until her hull filled with smoke and steam and water poured into her guts. Pushed by the tide, her engines failed, and she smashed into the net barrier, dragging it with her until she grounded well short of the channel.

Even then, Thetis served well. Her own guns firing nonstop, she drew most of the German fire on herself. Meanwhile, Iphigenia and Intrepid charged into the harbor. Taking their bearings from a green light on Thetis’s starboard quarter, they forged past her into the entrance to the canal, Intrepid leading the way. Intrepid’s captain, Lieutenant Stewart Bonham-Carter, got his ship well into the canal entrance and began to back and fill until he got his cruiser across the channel. Satisfied that his ship was placed correctly, Bonham-Carter ordered his men into the escape boats, started his smoke generators, and prepared to blow Intrepid’s bottom out. Before he could do so, however, his ship was struck by Iphigenia, driving down the canal in the cloud of Intrepid’s smoke after ridding herself of a barge she had rammed in passing. Intrepid was knocked out of position by the collision, but there was no fixing the problem, and Bonham-Carter blew his charges, settling the old cruiser across the channel.

Iphigenia’s commander, 22-year-old Lieutenant Edward Bilyard-Leake, fought the battle immaculately attired in a leather coat and steel helmet, looking like a uniform advertisement. Unperturbed in a blizzard of gunfire, he forced the bow of his ship into the silt between the bank and Intrepid, and got his stern into the bank on the other side. Satisfied, he blew his charges also and got his men off. When Keyes saw him after the raid, he was still impeccably groomed and unperturbed. Meanwhile, Thetis had managed to get one engine working again and pushed her way farther toward the canal entrance, finally getting crosswise in the channel and scuttling herself. All in all, it had been a remarkable achievement for all three ships.

The Bloodied Withdrawal

For the blockships’ crews, the submariners, and the landing parties, getting into Zeebrugge had been bad enough. Getting out again would be pure hell. On the western side of the mole, C3’s gallant crew had been picked up by a motor launch commanded by Lt. Cmdr. Francis Sandford, brother of the submarine’s commander. Under a curtain of fire that turned the water to froth, the fragile little boat headed for the safety of the Channel. Back inside the harbor, small, fragile powerboats were doing their best to get the blockship crews away. Intrepid had to get off both her complete crews. One of her two overloaded cutters was found by the destroyer Whirlwind, the other by an unarmed motor launch that had already picked up the crew of Thetis.

Iphigenia’s crowded cutter, battered and almost sinking, was lashed to another motor launch and nursed out of the rain of fire around the canal mouth. Only then did one of the rescued crew realize that Bonham-Carter had been left behind in the water, so the little boat turned again to pick him up before starting her run for the open sea. Her captain, young Lieutenant Percy Dean, took the launch in so close to the mole that the big German guns could not depress enough to fire on him, and the little boat tore past them to vanish into the night. Among the mortally wounded was Iphigenia’s lieutenant, a youngster named Lloyd, who still carried Iphigenia’s white ensign wrapped around his body. He was gutshot and knew he was dying, but he lived long enough to see Keyes after the raid. The admiral did what he could for the dying boy, making him a gift of the blood-soaked ensign he had died for.

On Vindictive, Carpenter knew it was time to go. Now that the blockships had charged home, his mission was complete. His shell-torn ship was jammed with dead and wounded, the surgeons below operating steadily in a blood-spattered makeshift hospital. It was the same on all the attack ships: aboard Iris an Army doctor attached to the Marines operated for 13 and a half hours straight in the ship’s purgatorial sick bay.

The Marines and Bluejackets still fighting on the mole were taking increased casualties. The withdrawal signal was supposed to be a blast on Vindictive’s siren, but it had long since been shot away. Daffodil still had hers, and the ear-shattering scream finally cut through the roar of battle. At once the surviving Marines and sailors began to fall back, fighting a series of rear-guard actions as they came, carrying their wounded and some of their dead. Lewis guns on the parapet covered the retirement, while the wounded were hauled up the 16-foot climb to the roadway, then up to the swaying gangways and across to Vindictive. Unwounded men in the comparative safety of the ship ran across the gangways, back onto the hell of the mole, to help carry the wounded to safety. By now, shells were hitting Vindictive from German batteries farther down the coast, fire against which the mole gave no cover.

Carpenter was hit at this time, along with his first officer and quartermaster, but all three men stayed at their posts. Then, as word was passed that the landing parties were back on board, Carpenter walked up a gangway onto the mole, standing calm and alone in the hail of German fire to make certain no one had been left behind. Vindictive and the two tough little Mersey ferries turned for home, belching covering smoke as they pulled away from the mole. Before she could hide herself entirely in the smoke, Iris II took a hit on the bridge that mortally wounded her captain, Commander Valentine Gibbs, and knocked out both her navigating officer and quartermaster. Drifting off course momentarily, she took shell after shell from the German batteries, until the two wounded men on her bridge got up, put her helm over, and headed for the open sea. As she turned, a motor launch cut between her and the blazing shore batteries, belching more of Brock’s impenetrable smoke. A providential shift in the wind began to carry the smoke cloud to shore.

Even so, Iris II was not safe yet. A fire raged forward of the bridge, and ammunition lay everywhere in its path. Able Seaman Lake and Lieutenant Henderson, the only survivors of the damage-control party, fought the fire alone and gradually beat it back. Lake dealt with the threat of the hot ammunition by grabbing it with his bare hands and throwing it overboard. Then, as the wounded steersman finally collapsed, Lake took the wheel in his blistered hands and nursed Iris home toward Dover. Behind Lake, sitting up against the bulkhead, was Signalman Tom Bryant, his legs shattered during the fight at the mole. Carried below, he realized he was the only signalman on board and insisted on being brought back to the bridge. There he remained until he finally passed out.

Eleven Victoria Crosses

Of all the small craft involved in the attack, only two motor launches had been lost to German fire. In both cases, most of the crew got off in small boats and were picked up by other Royal Navy units. Destroyer North Star, supporting the attack only 400 yards from the end of the mole, was crippled by shellfire. In spite of valiant attempts to tow her clear by sister destroyer Phoebe, North Star finally was abandoned, her crew saved by Phoebe. It was all over now except for getting home. Vindictive made Dover at 8 am the next morning. Daffodil was towed in five hours later by the destroyer Trident, and Iris II chugged home in midafternoon, down by the head but moving on her own engines.

The overall effect of the raid is debatable. Aside from the casualties inflicted on the German defenders, there is evidence that the blockships substantially closed the channel for a reasonable period of time. German figures, on the other hand, indicate that the raid made little difference in their ability to get their boats to sea. However, postwar salvage crews worked long and hard to clear Zeebrugge, and it was not until January 1921 that the channel could be freely used again. A subsequent raid on Ostend failed, as did an attempt to block the port. Proud Vindictive went to her death at last, this time serving as a blockship.

British casualties at Zeebrugge were 176 killed, 412 wounded, and 49 missing. The spirit of the survivors was incredible. Selflessly caring for one another during the arduous voyage home, their pride overcame much of their pain. One man who had lost both legs was asked if was sorry he had gone on the raid. He answered for the whole force: “No, sir, because I got on the mole.”

Whatever the long-term effect of the raid, Zeebrugge was a gallant flash of the old sea-dog spirit and a badly needed stimulant to British morale. Eleven Victoria Crosses were awarded between Zeebrugge and Ostend, a remarkable number of that rare decoration. Some were awarded by ballot, the survivors choosing who should be decorated, both for their own gallantry and for the courage of their comrades as well. The British nation as a whole was cheered by the knowledge that her Navy and Marines were as full of spirit and courage as they had ever been. Lord Nelson, who had lost an arm in a similar attack on Teneriffe in 1797, would have been proud of the men of Zeebrugge.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments