By Sam McGowan

In the minds of many military enthusiasts, there was only one bomber in the United States inventory during World War II. This is not true, of course, but historians focusing on the war in Europe have devoted so much paper and ink to the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress that it is often thought of as the only American bomber of the war, at least until the much larger B-29 Superfortress—also designed by Boeing—came along.

In reality, far more Consolidated B-24 Liberators were produced and were used more extensively than B-17s, both as bombers and in other roles. In fact, it was only in the Eighth Air Force that the B-17 was predominant. Thousands of Douglas A-20s, North American B-25s, and Martin B-26s, as well as excellent British bombers such as the Lancaster and Wellington, served in all theaters of war, but the “Fort” has come to symbolize the air war perhaps more than any other bomber.

Ironically, the B-17 was actually already outdated by the time the first Japanese bomb fell on Pearl Harbor, and its initial wartime introduction produced results so dismal that the British, who were the first to test it in combat, decided against the Boeing bomber and instead opted for the new Consolidated airplane that had been designed to replace it as their four-engine bomber import.

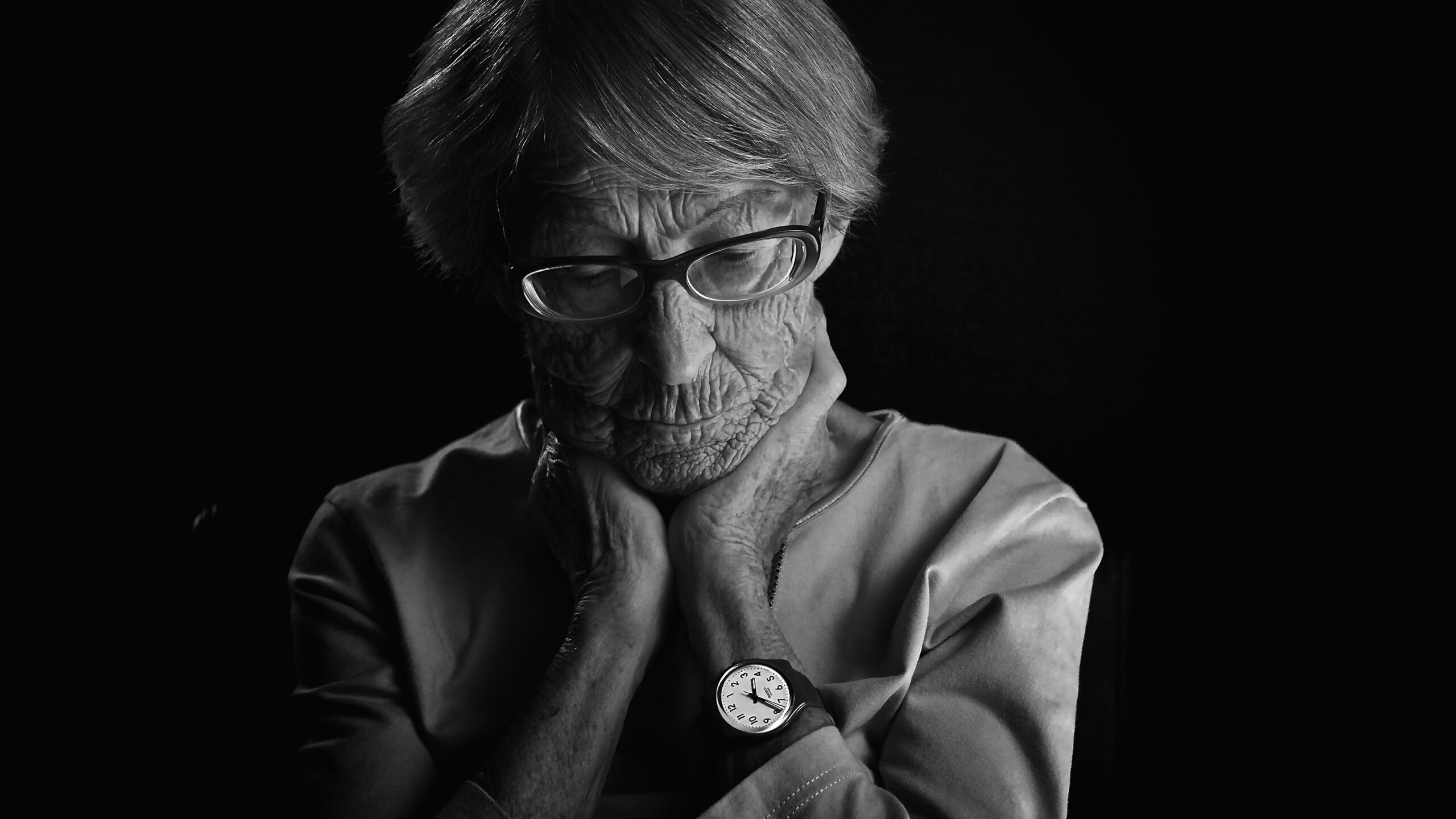

Nevertheless, thanks in large measure to the press, which romanticized the bomber far beyond its actual capabilities and accomplishments, the fame of the Flying Fortress achieved mythical proportions. Even its name allegedly came from a Seattle newspaper reporter, who dubbed the new bomber as a “flying fortress.” The young men who flew it in combat added to the myth, claiming it was the best and safest bomber ever built, in spite of the fact that they were enduring heavier losses than their peers in B-24s.

First flown in 1935, Boeing Aircraft Company’s B-17 was based on technology of the 1920s and early 1930s and was not the airplane the Army Air Corps actually had in mind for a long-range bomber. Consolidated’s B-24 was designed to replace the B-17 and was in many ways a much better airplane, with vastly improved performance due to an aerodynamically shaped wing that afforded higher speeds and greater payloads using engines with the same rated horsepower.

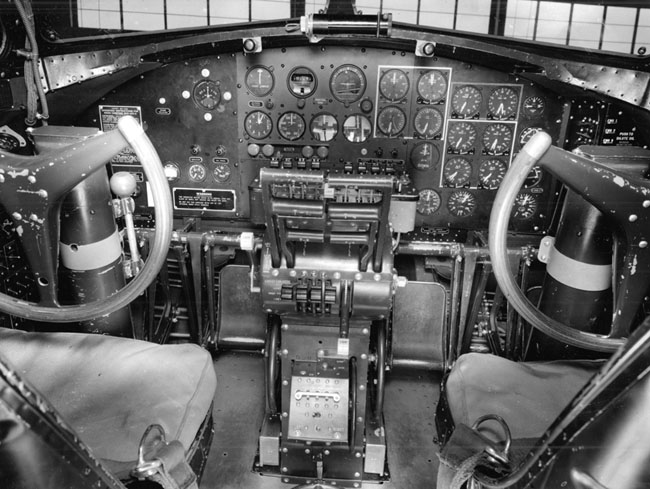

The B-17 was an all-electric airplane, while the B-24—and nearly every large airplane that followed—incorporated hydraulically operated landing gear, flaps, and other components that required far less maintenance than the numerous electrical servos that operated the B-17’s landing gear, flaps, and turrets. The B-17, nonetheless, was possessed of a design feature that made it able to absorb punishment and created a stable bombing platform: its huge wing possessed an extremely long chord (i.e., diameter between the leading and trailing edges), which produced considerable lift and featured large areas of empty space through which bullets and shrapnel could pass without doing substantial damage. But that same large wing also produced considerable drag, which limited the B-17’s speed and severely reduced its operational range.

The combination of the Clark Y wing and its lighter maximum gross weight did endow the B-17 with an ability to climb to higher altitudes than a Liberator, a feature that proved beneficial during the final months of World War II in Europe, when increasingly accurate German antiaircraft guns presented the major threat to bomber formations as German fighter attacks decreased. The big wing also made the airplane easy to fly due to the wing’s inherent stability and the light control inputs required to operate the ailerons.

The B-17 was an indirect result of U.S. Army thinking from years following the Great War, when Air Service leaders, led by the controversial Brig. Gen. Billy Mitchell, began pushing for the development of a “big bomber” with a 1,000-mile operating range for night missions and a 10,000-pound payload, a mission requirement that would not be met until the advent of the B-29 and Consolidated B-32 in 1942.

By the 1930s, aerodynamics and engine performance had advanced considerably, while U.S. public policy was turning toward using aircraft to defend the North American coasts. The need for long-range bombers capable of intercepting and attacking an enemy invasion force while it was still hundreds of miles out at sea led military planners to again seek a large bomber.

Although the new bomber lacked the performance the Army was actually seeking for a long-range bomber, it had some good qualities, including docile handling characteristics that made it popular with young pilots, whose training had been in biplanes. The Air Corps officers who flew it were convinced the new B-17 was the best bomber in the world, and the service’s senior leadership was eager to procure more, since it afforded new capabilities in aerial bombardment. An element within the Air Corps were becoming devotees of the concept of daylight precision bombing, and the B-17 offered a stable bombing platform that allowed bombardiers to drop their bombs with accuracy, at least in training situations from medium altitudes.

Plans were for two combat groups equipped with B-17s, one for each coast. An additional squadron of 13 airplanes had been authorized, and the Air Corps requested 50 more.

But military planning in the mid-1930s was geared toward homeland defense rather than strategic operations, and the purchase of several squadrons of huge land-based bombers was seen as a conflict with the Navy’s carrier-based bomber force, which at the time was equal to similar forces around the world. In 1936, no country had an air or sea arm capable of threatening the United States directly, nor was there any likelihood one would in the foreseeable future.

The B-17 was saved from obscurity by the course of world events and the emphasis of President Franklin Roosevelt on building up the U.S. military, especially its air forces. Gathering war clouds over Europe presented an excuse to ask Congress to appropriate money for military projects.

With his party controlling both the executive and legislative branches of government, Roosevelt was able to push through legislation authorizing a massive defense budget, and a military that had been starved for funds suddenly found itself with a blank check to purchase more equipment, particularly aircraft, and to recruit men to equip newly constituted combat units. At the time, only 13 B-17s were in the inventory, but an additional 40 were now ordered.

The B-17 was not, however, the bomber the Army had decided it really wanted. It was lacking in range, speed, and payload, so the War Department put out a new specification for a four-engine bomber with increased performance to replace the B-17 until a true, long-range bomber could be developed. The contract for the new bomber was awarded to Consolidated Aircraft for its new B-24.

Even though the B-17 had been in existence since 1935, production had been limited at least in part due to Boeing and the Army’s desires to improve the airplane’s performance. This was achieved by the addition of superchargers, which allowed later models to operate as high as 35,000 feet at lighter weights, and the output of the Curtiss-Wright engines was eventually increased to 1,200 takeoff-rated horsepower.

The RAF was the first to fly B-17s in combat

By 1940, war had broken out in Europe, and Britain’s Royal Air Force was eager to try out the new bomber. The Army Air Corps was anxious to see what the airplane could do under combat conditions, and 20 B-17Cs were diverted from U.S. production under the Lend-Lease Act for delivery to Britain, where they were designated by the RAF as Fortress I and assigned to No. 90 Squadron RAF.

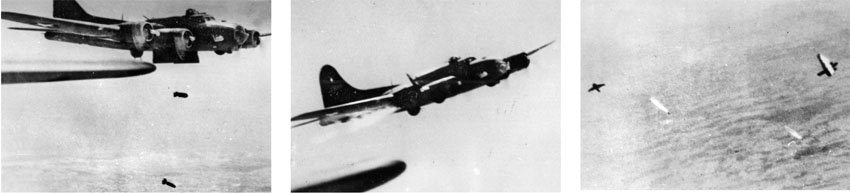

The record of the Fortress I was dismal. During the first mission, the guns froze up and became useless, and one airplane was forced to divert due to engine trouble. The second mission caused no damage to the target, and one of the bombers was shot up so badly that it could not be returned to service. It was the second Fortress I to be lost (the first to be delivered ground-looped on landing, ran off the runway, and had to be scrapped for parts).

The third combat mission—against Oslo, Norway—saw the loss of all three bombers on the mission to fighter attack. After just over a month of operations, eight of the 20 airplanes had been lost either in combat or to accident, and the RAF decided it wanted nothing more to do with the Boeing bomber. Although four of the Fortress I’s were sent to North Africa, where they operated as night bombers exclusively, the remaining Fortresses were transferred to RAF Coastal Command for coastal patrol.

The RAF decided against accepting any more Fortresses and instead opted for the new Consolidated four-engine bomber that had been designed as its replacement and was beginning to come off the production lines. It was not until late 1942 that the RAF accepted any more B-17s, and they were used primarily for coastal patrol and electronic countermeasures work.

The B-17’s failure in combat led to severe criticism of the RAF, even though the RAF had used them as daylight bombers on unescorted missions depending on their own armament to defend against fighters. just as the U.S. Army planned to do if the country went to war.

Fortunately for the young men who went to war with the Eighth Air Force in England, the shortfalls in the B-17’s designs had been recognized, and newer models had been produced with fixes that rectified some of the problems first encountered by the British . Nevertheless, B-17 crews would suffer horrendous losses until suitable escort fighters were developed to accompany them to and from their targets.

B-17s in the Pacific Theater

Although the B-17 is best known for its service with the Eighth Air Force in England, the airplane’s first use in combat by American forces was on the other side of the world, in the Philippines and Southwest Pacific. Under the Rainbow Plan for national defense, the War Department initially wrote off the Philippines as indefensible, but as Japanese aggression in the region increased, President Roosevelt decided that the islands could serve as a base from which to defend against further expansion of Japan’s Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere.

In the summer of 1941, the War Department began building up military strength in the Philippines, including deploying a large heavy-bomber force made up of B-17s and B-24s. In August 1941, the War Department decided to move the first heavy bombers to Clark Field, and the 19th Bombardment Group was alerted for the move.

War Department plans called for a total heavy bomber force of 165 bombers by the spring of 1942. About half would be B-17s complemented by a similar number of B-24s.

Popular myth has long held that U.S. forces in the Philippines were unprepared when war broke out. “Understrength” is a more appropriate description. General Douglas Mac-Arthur’s Philippines Department was feverishly preparing for war while hoping that it would not come until sometime after the first of the year, by which time military strength in the islands would have greatly increased.

Lieutenant General Lewis H. Brereton, the senior Air Corps officer in the department, took steps to protect his forces by deploying his fighter squadrons at several bases around Luzon. On December 4, with war barely four days away, he ordered two of the 19th Bombardment Group’s four squadrons to Del Monte Plantation on Mindanao. Consequently, half of the B-17s in the Philippines were spared when Japanese bombers struck Clark around mid-day on December 8. Even then, the bomber force was not caught by surprise as is so commonly believed, but fell victim to a stroke of bad luck.

Earlier in the day, the two squadrons had been ordered aloft on scouting missions after word came of the attacks on Hawaii but had been recalled to rearm and refuel for an attack on Japanese airfields on Formosa that afternoon. Unfortunately, both squadrons were still on the ground when a Japanese formation bombed and strafed Clark Field, and except for three airplanes, the entire force was damaged beyond repair by strafing fighters.

Maintenance crews worked feverishly to repair the damaged bombers, but freak accidents destroyed all three before they could fly an operational mission. Still, half of the heavy-bomber component in the Philippines was not touched, and the two remaining squadrons would form the nucleus of the air force that would ultimately defeat the Japanese in the Southwest Pacific.

The 16 B-17s at Del Monte continued operating in the Philippines for the next two weeks, until Roosevelt decided to abandon the islands and the remnants of the 19th Group were ordered to Australia, where they took up station at Batchelor Field near Darwin. Before the B-17s departed, several attacks were flown against Japanese ships and landing parties at Viggan with some success, but losses and maintenance requirements took their toll.

One of the B-17s that attacked Viggan was flown by Captain Colin P. Kelly and his crew. After being attacked by fighters, most of the crew bailed out over Clark, except for Kelly and the copilot, who remained on board. Before they could jump, the airplane exploded and threw both pilots out. Kelly’s parachute did not open, and he was killed. He was posthumously awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and became the first American hero of the war.

MacArthur’s orders were to defend Australia, and the growing force of B-17s under his command was put to work attacking Japanese installations in New Britain and the Solomon Islands. The bomber force was reduced, at least on paper, when the 7th Bombardment Group was ordered to India to form the bomber command for the new Tenth Air Force. Only six airplanes and crews made the move, most of them transferred to the 19th.

The 19th Group left Darwin and moved to Townsville, from which it staged airplanes and crews through Port Moresby for attacks against Rabaul, which had become the main Japanese supply and staging base in the Southwest Pacific. A mission required the crews to take off from Townsville and spend the night at Moresby, where ground crews serviced the airplanes while the flight crews attempted to get some sleep either on the ground or on the wings of their bombers.

They would take off in the wee hours of the morning and cross the rugged Owen-Stanley Mountains, then proceed out across the Bismarck Sea to their target. Missions were small, consisting of no more than three airplanes, and were usually timed so that the bombers would arrive over the target before dawn. Damage to the target was probably minimal at best, but at least the crews were striking a blow against Japan.

The B-17’s record in the Philippines, Java, and the Solomons was good. Crews came back from missions in airplanes that had suffered considerable damage from fighter attack, although the damage was often more to the skin rather than structure. That B-17s often returned after taking numerous hits in the huge wings and massive tail. giving rise to the myth that the Flying Fortress was “more rugged” than its sister Liberator.

In truth, both airplanes were able to continue flying after absorbing numerous hits from fighters and shrapnel from flak, and both were susceptible to fatal damage from cannon hits in structural areas. The B-17’s wide wings and large tail simply offered more surface and were more likely to be hit than the slim wings and smaller twin vertical stabilizers of the B-24.

In late July 1942, Lt. Gen. George C. Kenney arrived in Australia to assume the role of MacArthur’s air boss. His first act was to ground the entire bomber force for maintenance in anticipation of mounting a large-scale attack on Rabaul in preparation for the impending landings on Guadalcanal.

The V Bomber Command managed to get 15 airplanes over Rabaul the day of the Guadalcanal landings. From then on, missions were scheduled with as many airplanes as possible, although small formations and even single airplanes continued operating against Japanese shipping at night. Shortly after his arrival, Kenney also decided to send the veteran 19th Group back to the U.S. The group had been in constant combat since the previous December 8, and its crews were worn out, both physically and emotionally. The 43rd Group had arrived from the United States and would become the primary heavy bomber group in the Southwest Pacific until the arrival of the B-24-equipped 90th Group. The 43rd was the last B-17 group sent to the Pacific.

The B-17 force continued low-level attacks against shipping at night, but their days in the Southwest Pacific were numbered. War Department priorities combined with the superior range and payload of the B-24 led to the closing of the chapter on the B-17’s role in the Pacific War. By the end of 1943, all of the B-17s in the theater had been replaced with B-24s, and all new groups coming in flew Liberators.

B-17s with the Eighth Air Force

Army Air Forces plans had actually called for the B-24 to be the service’s primary bomber, and most of its senior officers preferred the Liberator due to its increased payload, speed, and range. The exception was among the staff of the Eighth Air Force, which deployed to England in the summer of 1942, and Jimmy Doolittle, who went to North Africa to command the new Twelfth Air Force after returning from the Tokyo Raid.

Eighth Air Force was conceived as the U.S. Army Air Forces element to wage war against Germany from bases in England. Although the original unit was a conventional air force consisting of a full range of bomber components (heavy, medium, and light), as well as a fighter component, it had become solely a heavy bomber organization supported by fighter and troop carrier commands by the time it moved overseas in July 1942.

The first U.S. B-17 mission in Europe was flown on August 17, 1942, by a dozen 97th Bombardment Group B-17s against the railroad marshalling yards in the French city of Rouen. The Rouen mission was designed for publicity purposes to announce that the U.S. Army Air Forces were commencing combat operations against German targets in Western Europe.

The raid’s main objective was to create newspaper headlines. Escorting Spitfire fighters accompanied the bombers to and from the target, and there were no losses. Surprisingly, bombing results were determined to have been quite good. American B-17 missions were off to a good start, especially in comparison to the early British efforts, but since they were fairly short missions against targets in France, they encountered little opposition. Six missions were flown before the B-17s endured their first fighter attacks. Three more missions were flown without loss, but on the tenth mission, two Fortresses went down.

U-boats were taking a heavy toll on shipping, and the destruction of the pens where the submarines sheltered between sorties became a major objective. After October, the main targets for the heavy bombers were the submarine pens in northern France.

Reports by the B-17 gunners indicated that they were taking a heavy toll on their attackers, but postwar analysis of German records reveals that these claims were greatly exaggerated. Heavy bomber operations from England in the fall of 1942 were designed more to garner publicity than anything else. That began to change with the arrival of more aircraft and crews.

The few winter missions that were mounted were against targets in France and occupied Europe, particularly submarine bases along the Bay of Biscay. The B-17s lacked the numerical strength to go into Germany unescorted, and the escorting Spitfires were only capable of operating a short distance across the English Channel.

On January 21, 1943, the Combined Chiefs of Staff issued what is commonly known as the Casablanca Directive, an order for a combined bomber offensive from the United Kingdom, with American bombers attacking by day while their British counterparts continued the night attacks the RAF had been mounting for nearly two years. Up to this point, Eighth Air Force bombers had yet to appear in the skies over Germany.

The experiences of the early missions over France indicated that the heavy bombers were incapable of adequately defending themselves against the hordes of Luftwaffe fighters they could expect to encounter once they started penetrating German airspace. German antiaircraft defenses were known to be formidable, as British losses on their night missions illustrated.

Eighth Air Force commenced operations into Germany in the late winter of 1943 and quickly learned that they could not be conducted without tremendous loss. The deeper into German airspace a mission went, the greater the losses. Few American fighters were based in England at the time, and the Spitfires with which VIII Fighter Command had equipped its squadrons lacked the range to go further than France.

The lack of an adequate escort fighter led Eighth Air Force to seek to convert a number of B-17s and B-24s into heavily armed escorts. Designated as YB-40s, the modified Fortresses were equipped with additional guns and carried large quantities of ammunition in the bomb bays. While the concept looked good on paper, in practice the YB-40s proved generally ineffective. Their heavy armament made them considerably slower than the already slow bombers, thus reducing combat speeds and making the B-17s more vulnerable to fighters than they already were. The one good thing that came out of the project was the chin turret, which was adopted for all future B-17 production.

To improve its escort capabilities, VIII Fighter Command began receiving Republic P-47 Thunderbolts in the spring of 1943. The P-47s were heavy, and the former Spitfire pilots didn’t like them, but they quickly proved to be formidable fighters, and with the addition of external fuel tanks, they were capable of operating far deeper into German-held territory than any other fighter had previously gone. Still, even with additional fuel, the P-47s were only able to go a short distance into German skies. Once the escorts turned away, the bomber formations were left to fend for themselves against ever-increasing numbers of Luftwaffe fighters.

Without adequate escorts, losses among the B-17s were astronomical. The prewar belief that “the bomber will always get through” was proving to be true, but only when the bombers operated in large formations; and even then, losses were high.

A decision was made: All future B-17 production would be sent to Europe to replace combat losses and to equip B-17 groups that were then in the training pipeline; all but two future combat groups would be equipped with B-24s.

In the summer of 1943, the B-17s were left alone in England, as all VIII Bomber Command Liberators were sent to Libya to support the invasion of Sicily and fly the most famous air-raid of the war, the daring low-level attack on the oil refineries at Ploesti.

On August 17, the anniversary of the first Eighth Air Force B-17 mission, VIII Bomber Command suffered its worst losses to date. A force of 376 B-17s was sent against Messerschmitt factories at Regensberg and the ball-bearing plants at Schweinfurt. The two-pronged mission was part of a plan that included an attack on aircraft factories at Weiner-Neustadt in Austria by Eighth and Ninth Air Force B-24s in concert with the B-17 missions over Germany.

The Weiner-Neustadt mission went off on August 13, but the Regensberg-Schweinfurt mission was delayed for four days. The Schweinfurt attack was assigned to the 1st Bombardment Wing, which was to return to its bases in England. The B-17s of the 4th Bombardment Wing were equipped with long-range fuel tanks and were to continue on to North Africa to refuel and rest in the first experiment with shuttle bombing.

Strong fighter opposition was expected, and 18 squadrons of P-47s and 16 of Spitfires were planned as escorts. Once the escorts reached the limit of their range, the German fighters came in. A total of 60 B-17s failed to return from the mission or reach the shuttle bases in North Africa: 36 from the Regensberg force and 24 from the Schweinfurt mission. Nearly all fell victim to fighter attack. It was becoming obvious that unescorted missions into Germany were too costly to continue.

On October 14, VIII Bomber Command returned to Schweinfurt. This time, 291 1st and 3rd Air Division B-17s were joined by 2nd Air Division B-24s, which were supposed to fly a considerably longer, more southerly route to the target. Early autumn thunderstorms over England created problems for the formation. While the B-17s were able to eventually assemble, the B-24 force was restricted due to bad weather, so the formation leader decided to take the Liberators on a diversion toward Emden instead.

The Germans were not fooled by the feint, and as soon as the escorts left the B-17s, fighters pounced on them in force. It was a repeat of the previous mission against Schweinfurt, only worse. Once again, 60 B-17s and their crews were lost, while 17 others returned with major battle damage. As a result of the Schweinfurt mission and other heavy losses during a six-day period that claimed more than 80 additional bombers and their ten-man crews, Eighth Air Force decided to halt further missions into Germany until the escort problem had been solved.

In September 1943, some B-17s were equipped with H2X radar navigational equipment, which allowed blind bombing using radar to mark the release points for bombs. The VIII Bomber Command developed a new lead-crew system that used crews trained in radar bombing to mark the point at which formations released their bombs in synchronization with the lead bombardiers who bombed visually, if possible, but by radar if the target was obscured by clouds.

By early 1944, as weather conditions over Europe deteriorated, radar and synchronized bombing had become a normal mode of operation. Eighth Air Force planners had developed a standard calling for the maximum number of bombs to fall within a 1,000-foot circle around the target, and missions were planned using a “shotgun” method calling for maximum tonnage on the target rather than the precision bombing that had been so heavily emphasized before the war and which had proven impossible under combat conditions.

By early 1944, the escort problem had been solved, as more P-38s became available in England and the effective range of the P-47s was greatly increased. Redesigned North American P-51 Mustangs were also becoming available, although it would not be until mid-1944 that their numbers were increased to the point that they became truly effective in the escort role.

With the escort problem solved, the bombers returned to Germany with a major effort against aircraft manufacturing facilities during the last week of February. Eighth Air Force formations came in from England while Fifteenth Air Force came up from Italy in a coordinated effort. The goal was to destroy the Luftwaffe and gain complete air superiority over Western Europe in preparation for the invasion of Normandy. German aircraft manufacturing was the primary target, with the oil and transportation industries also given high priorities. Another major effort was aimed at the V-1 and V-2 rocket-launching facilities in France.

From February 1944 until the end of the war, the heavy bomber mission was essentially the same: a strategic campaign to destroy German industry. After the Normandy invasion, some missions were aimed at tactical targets, but the strategic campaign continued. With escort fighters able to keep the Luftwaffe at bay, increasing losses to flak as accuracy improved became a major concern.

Bomber formations were forced to fly higher and higher to avoid the flak, and increasingly heavy armor was added to the B-17s and B-24s. Fortunately, the B-17’s huge wing allowed the Flying Fortresses to operate at higher altitudes, although their airspeed and range suffered as their weight was increased with the addition of more and more armor. The reduction in fighter attacks reduced the necessity for speed, which had been the B-17s main deficiency, while Allied advances into Europe and ultimately into Germany reduced the need for elaborate routes to and from the targets and the need for excess range.

In late 1943, General Doolittle took command of the new Eighth Air Force. Doolittle, who had achieved celebrity status before the war as an air racer, became popular with the senior British officers on the Allied staff while he commanded Twelfth Air Force in North Africa, and when General Dwight Eisenhower and his staff were ordered back to England, they pressed for Doolittle to go with them.

Doolittle had a special fondness for the B-17 and undisguised dislike for the B-24. The halting of unescorted bomber missions into Germany led to a decline in bomber losses and made more B-17s available. In mid-1944, Doolittle began converting the B-24 groups in 3rd Air Division to B-17s as the first step to converting the entire VIII Bomber Command to the Boeings.

Doolittle’s justification for the planned switch was that the B-24s were more vulnerable to antiaircraft fire due to their being forced to operate at lower altitudes as their operational weights were increased with additional armor. His plans were thwarted by the impending end of the war and Headquarters, U.S. Army Air Forces’ decision to suspend B-17 production so that the facilities could be used to produce B-29 Superfortresses for the air campaign against the Japanese home islands.

By that time, however, the issue had become moot. Allied ground forces had driven Germany’s forces back into the homeland. The need for strategic bombing was decreasing, and the War Department’s attention had turned toward the defeat of Japan. It was a campaign in which the B-17 would have no combat role.

When the war in Europe came to an end, most of the B-17s headed for the scrap pile, not to the Pacific. The War Department decided to transfer the Eighth Air Force to Okinawa, but none of its B-17s would take part. Instead, it would become a second heavy bomber force, equipped with B-29s. Although Eighth Air Force Headquarters moved to Okinawa, the war ended before it became operational.

Sam McGowan is a retired pilot and Vietnam veteran. He is the author of numerous works on varied topics related to World War II and resides in Missouri City, Texas.