By Don Hollway

When the end came, on April 2, 1865, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was sitting in his customary pew at St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Richmond, Virginia. A messenger interrupted the Sunday service to deliver a sealed telegram from General Robert E. Lee, then some 25 miles to the south defending Petersburg. “I advise that all preparation be made for leaving Richmond tonight,” Lee reported tersely.

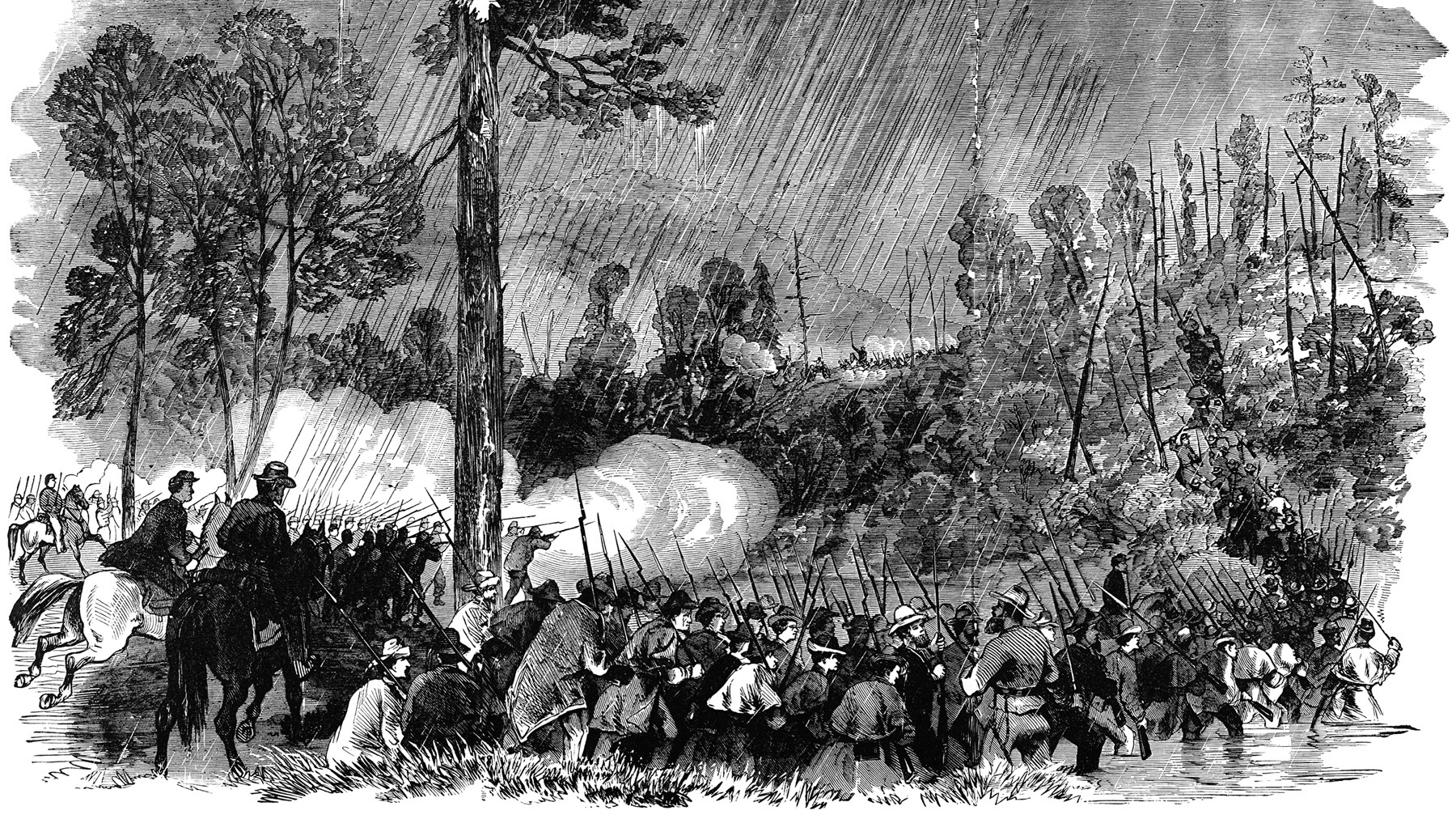

For the better part of a year, Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia had held off three Union armies under Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, but the previous day the Federals had finally broken through at Five Forks. With Union troops threatening his main line of supply and retreat, Lee had no choice but to abandon Petersburg and race west, away from the capital. Richmond was doomed. As president, Davis’s task had suddenly become to lead the Confederacy in defeat more adeptly than he had ever led it in victory.

Escaping With the CSA’s Treasury

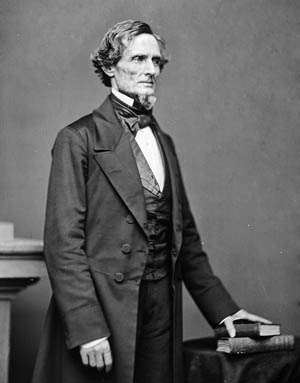

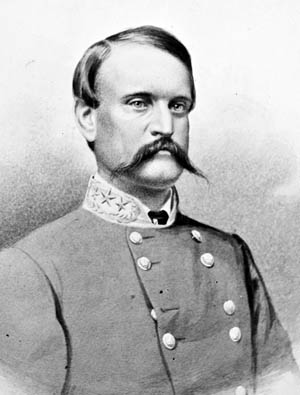

Having commanded the 1st Mississippi Regiment in the Mexican War, the West Point-educated Davis fancied himself something of a military expert. He had desired to serve the Confederacy not as its president but as overall commander of its armies and endeavored to run the nation as a military operation. Autocratic governance, however, had proven ineffective in a nation based on states’ rights. Southern governors largely went their own way, sending or withholding troops as they saw fit and printing their own money. Inflation was near 6,000 percent, and the Confederacy was $700 million in debt. There had been food riots in Richmond, and city matrons had been reduced to serving river water at “starvation balls.” On the war front, Davis had accepted slaves into Confederate armies with a promise of freedom for those who fought, but Southern troops were still outnumbered 10-to-1. When Lee surrendered, it was left for Davis to carry on alone.

“I went to my office,” Davis recalled, “and assembled the heads of departments and bureaus, as far as they could be found on a day when all the offices were closed, and gave the needful instructions for our removal that night, simultaneously with General Lee’s withdrawal from Petersburg.” Each department head was to see that important documents and records were packed and ready to go and the rest destroyed. Leftover stores of cotton and tobacco were to be burned. The remaining national treasury of some $500,000 in gold nuggets, double eagles, silver bars, and Mexican coins was to be crated and taken along. The government would entrain for Danville, on the North Carolina border, at eight that evening. Anyone and anything not on board then would be left behind. The meeting was cut short by the rumble of cannon fire in the distance.

Davis hurried home to the Confederate White House at Clay and 12th Streets to wind up his personal affairs. The house was largely empty. “In view of the diminishing resources of the country on which the Army of Northern Virginia relied for supplies, I had urged the policy of sending families as far as practicable to the south and west,” wrote Davis, “and had set the example by requiring my own to go.” On Wednesday he had put his wife Varina and their children on board a train to Charlotte, North Carolina, giving her a revolver and instructing her in its loading and firing. “If I live you can come to me when the struggle is ended,” he told her, “but I do not expect to survive the destruction of constitutional liberty.” As he put them on the train, his daughter Maggie hugged his leg and his son Jeff burst into tears and begged to stay with his father. Varina thought her husband appeared “as though he was looking his last upon us.”

Davis had auctioned off the family horses, silver, and valuables for $28,400. He sent Confederate treasurer John Hendren with the check to the Bank of Richmond. Hendren returned with the news that the bank would not cash it, even when presented by the treasurer of the Confederacy on behalf of its president. The banks were choked with customers clamoring for their deposits, even as officials piled together millions in worthless paper notes for burning. Meanwhile, bank officials insisted on sending junior managers along to supervise the guarding of the government treasury, half of which legally was theirs.

The Last Train Out of Richmond

At dusk Davis left for the train station through a city rapidly sinking into chaos. Frank Lawley, correspondent for the London Times, reported, “During the long afternoon and throughout the feverish night, on horseback, in every description of cart, carriage, and vehicle, in every hurried train that left the city, on canal barges, skiffs, and boats, the exodus of officials and prominent citizens was unintermitted.”

Liquor poured into the gutters to deny the invader was instead scooped up by rowdies and hooligans as taverns and saloons emptied and crowds gathered in the streets. Supply houses and depots were thrown open to the citizens, who had been too long denied. “The most revolting revelation,” wrote Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s wife, LaSalle, “was the amount of provisions, shoes and clothing which had been accumulated by the speculators who hovered like vultures over the scene of death and desolation. Taking advantage of their possession of money and lack of both patriotism and humanity, they had, by an early corner in the market and by successful blockade running, brought up all the available supplies with an eye to future gain, while our soldiers and women and children were absolutely in rags, barefoot and starving.” The crowd’s mood soon turned ugly.

The scene at the station was little better. The last trains out of the city sat huffing on the line. Troops endeavored to control the refugees jamming the platform, the insides and tops of the passenger cars, boxcars, freight cars, and even the locomotives. The treasury gold had been boxed and loaded, with 60 cadets from the naval academy drafted to guard it. Davis calmly awaited any last-minute reprieve from Lee at Petersburg. None came. Finally, at 11 pm, the president boarded last and the trains pulled out for Danville.

With government authority gone, Richmond quickly tumbled into anarchy. The last of the city garrison pulled out in the early hours. Throngs of maddened citizens, deserters, and criminals newly escaped from the state prison became mobs of drunken rioters and looters. Fires from government storehouses spread to the city, punctuated by explosions from ammunition magazines and ironclads scuttled at the riverfront, blowing out windows two miles away. By dawn a third of the city, including the entire business district, was on fire.

Continuing the War

Meanwhile, along the 140-mile run to Danville, plans took shape for carrying on the war. “The design,” wrote Davis, “as previously arranged with General Lee, was that, if he should be compelled to evacuate Petersburg, he would proceed to Danville, make a new line of the Dan and Roanoke Rivers, combine his army with the troops of [General Joseph E.] Johnston in North Carolina, and make a combined attack upon [Maj. Gen. William T.] Sherman.”

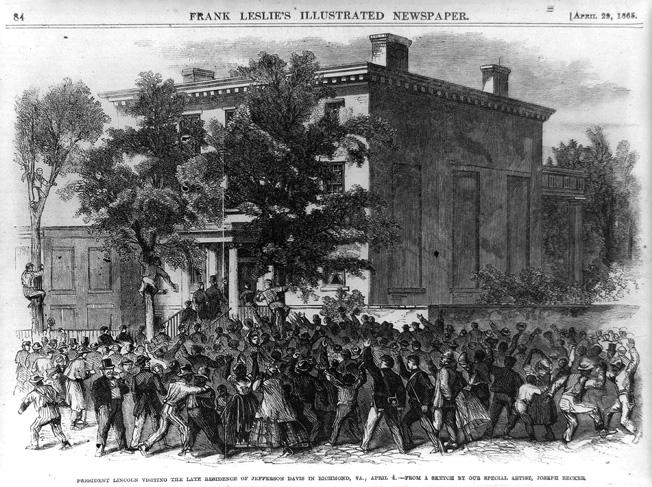

Parts of Richmond were still burning at 9 am on Tuesday, when Abraham Lincoln and his son Tad, turning 12 that day, disembarked on the riverfront. They walked the two miles or so to the Confederate White House, escorted only by a handful of high-ranking officers and, almost immediately, a throng of jubilant ex-slaves. “[Lincoln] walked through the streets as if he were only a private citizen, and not the head of a mighty nation,” reported the Boston Journal. “He came not as a conqueror, not with bitterness in his heart, but with kindness.” At the presidential mansion Lincoln was shown the office Davis had vacated 40 hours earlier. Colonel Thomas Thatcher Graves recalled, “As he seated himself he remarked, ‘This must have been President Davis’s chair,’ and, crossing his legs, he looked far off with a serious, dreamy expression.”

In Danville, Davis knew none of this. Telegraph lines from the north had been cut. It was not until Saturday that the president learned that Lee had been trapped near Appomattox, and Monday when word came of his surrender. Davis did not for a moment contemplate following his commanding general’s example. “Certainly better terms for our country could be secured by keeping organized armies in the field,” he wrote, “than by laying down our arms and trusting to the magnanimity of the victor.” He wired Johnston of the change in plans. With Lee out of the war, he said, they would meet in Greensboro, North Carolina, the headquarters of General P.G.T. Beauregard. There was no time to lose. Union horsemen were reportedly already closing in. If the rails to Greensboro were cut, it was all over for Davis and his party.

“A Miss is as Good as a Mile”

The scene at the Danville station was, if anything, even more desperate than at Richmond. Ten passenger cars were not enough to accommodate all those seeking to escape. Two more cars were added over the protests of the train crew, who were proven right when their old locomotive blew a cylinder just a few miles out of town. The government sat defenseless on the line until another engine could be brought up. Their escape was so narrow that Union cavalry burned a railroad bridge just moments after the train passed over it. With so little to cheer about, Davis smiled when he heard the news. “A miss is as good as a mile,” he joked.

Behind them Dansville went the way of Richmond. Two companies of troops left behind to maintain order and protect stores were not up to the task. “Our children and we’uns are starving,”cried a woman at the head of a mob, “the Confederacy is gone up; let us help ourselves.” The troops gave way and the looting began, at least until a nearby ammunition train caught fire and exploded, killing 50 people. Thinking that Federal forces had attacked, the rioters scattered in panic.

Citizens of Greensboro, long a hotbed of Union sympathies, did not look forward to sharing the same fate as Richmond and Danville. No crowds welcomed the presidential train. What little sympathy and interest the fugitive officials received mostly involved interest in the treasure known to be on the train. A colonel of the guard recalled, “We were reported to have many millions of gold with us.”

Davis’ April 13th Strategy Meeting

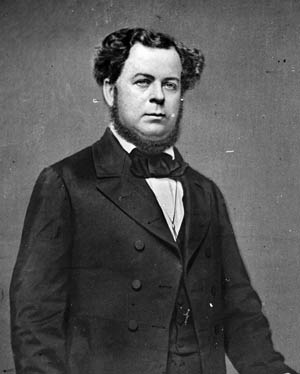

Most officials didn’t even bother to disembark but set up living spaces aboard the train. National affairs were run out of a dilapidated, leaky “cabinet car.” Secretary of the Navy Stephen Mallory recalled that matters of state sovereignty and secession mattered less than “more pressing and practical questions of dinner or no dinner, and how, and when and where it was to be had, and to schemes and devices for enabling a man of six feet to sleep upon a car seat four feet long.” For his new White House, Davis took a 12-foot by 16-foot boardinghouse room with a single bed, table, and chair, in which he convened a strategy meeting on Thursday morning, April 13.

Reports by Beauregard and Johnston were not encouraging. Mobile had fallen; Raleigh was on the verge of surrender; Sherman was just 50 miles from Greensboro. Johnston estimated that he could field about 25,000 troops. Grant and Sherman, by contrast, had about 350,000 under arms. Davis, however, still planned to enlist fresh conscripts and rally deserters to the flag. “An army holding its position with determination to fight on, and manifest ability to maintain the struggle, will attract all the scattered soldiers and daily rapidly gather strength,” he maintained.

His generals, to put it mildly, thought Davis deluded. Neither Beauregard nor Johnston had ever held Davis in particularly high regard. Johnston in particular still harbored a grudge against the president for relieving him of command at Atlanta in 1864. “I represented that under such circumstances it would be the greatest of human crimes for us to attempt to continue the war,” Johnston remembered, “for, having neither money nor credit, nor arms but those in the hands of our soldiers, nor ammunition but that in their cartridge-boxes, nor shops for repairing arms or fixing ammunition, the effect of our keeping the field would be, not to harm the enemy, but to complete the devastation of our country and ruin of its people. I therefore urged that the President should exercise at once the only function of government still in his possession, and open negotiations for peace.”

Beauregard, who had ordered the first shots of the war fired on Fort Sumter, South Carolina, and frequently clashed with Davis over military strategy, did not side with him now. “I concur in all General Johnston has said,” the New Orleans native admitted. So did most of the cabinet. “I yielded to the judgment of my constitutional advisors, of whom only one held my views,” Davis remembered, “and consented to permit General Johnston, as he desired, to hold a conference with General Sherman.”

To Charlotte by Horse

The next morning, April 14, Lincoln convened his own cabinet meeting in Washington, including General Grant. The major topic concerned the fate of Confederate leaders. “All the gentlemen present thought that, for the sake of general amity and good-will, it was desirable to have as few judicial proceedings as possible,” remembered one official. “Yet would it be wise to let the leaders in treason go entirely unpunished?”

Another asked, “I suppose, Mr. President, you would not be sorry to have them escape out of the country?” “Well, I should not be sorry to have them out of the country,” Lincoln joked, “but I should be for following them up pretty close, to make sure of their going.”

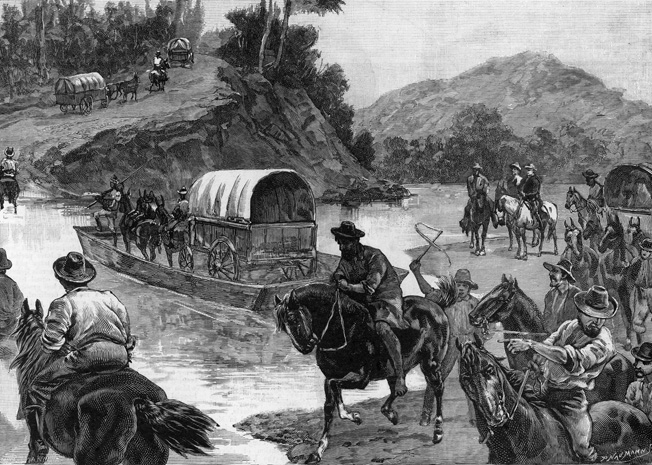

In Greensboro, the going had become no easier. Since Union forces had cut the rail line south to Charlotte, the Davis party could only proceed on horseback. The treasury funds were divided, with $39,000 in silver left to Beauregard and $288,000 loaded onto wagons, along with most government records and papers. Recent rain having turned the roads to mud, an artillery unit was drafted into service to manhandle the wagons. Tennessee and Kentucky cavalry units, about 1,300 riders in all, were enlisted as escorts. With that, the Confederate government vanished into the countryside.

“Great curiosity is naturally felt North and South to learn what has become of Jefferson Davis,” stated the Richmond Evening Whig, “the head of the greatest rebellion the world has yet seen.” And a South Carolina newspaper admitted, “We would like to inform our readers where these gentlemen [Davis and the Cabinet] are and what they are doing but we cannot.” “We honor and trust him still, and hold the opinion that he will yet prove himself to be what we thought him when we placed him in the presidential chair.”

“They Shall Suffer For This”

Not until Wednesday did the presidential party finally surface in Charlotte. By then Varina and the children had already gone on ahead to Abbeville, South Carolina. Johnston and Sherman had reached an accord, sent to Washington for approval. Only then did Davis learn that final approval of the terms would not come from Lincoln. A messenger delivered a telegram: “President Lincoln was assassinated in the theatre on the night of the 14th inst. Secretary Seward’s house was entered on the same night, and he was repeatedly stabbed, and is probably mortally wounded.”

Conspiracy enthusiasts and vengeful Unionists would ever afterward accuse Davis of giving the assassins their orders and, upon hearing news of their mixed success, misquoting Macbeth: “If it were to be done it were better it were well done.” More sympathetic witnesses said he seemed genuinely shocked by the news. “I certainly have no special regard for Mr. Lincoln,” said Davis, “but there are a great many men of whose end I would much rather have heard than his. I fear it will be disastrous to our people, and I regret it deeply.”

During their time together in Congress, Lincoln’s successor, Andrew Johnson, a War Democrat, Southern Unionist, and former slave owner, had lumped Davis in with what he scorned as the South’s “illegitimate, swaggering, bastard, scrub aristocracy.” As recently as the afternoon of the assassination, Johnson had advised Lincoln not to be lenient with rebels and traitors. And as a fellow target in the murder plot (his assigned killer, George Atzerodt, had lost his nerve and got drunk instead), Johnson had come away from Lincoln’s deathbed swearing, “They shall suffer for this.”

The Surrender of Joseph E. Johnston

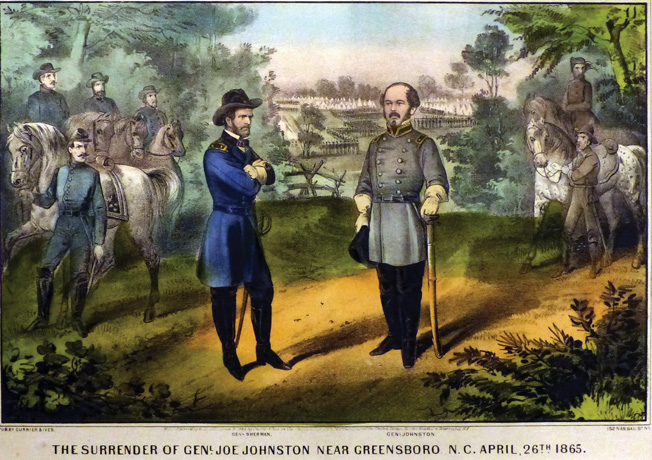

Sherman, acting on Lincoln’s wishes, had offered Johnston terms even more generous than those Grant had offered Lee, but not simply to obtain a military surrender. The stakes were nothing less than the final dissolution of the Confederacy. Now that was up in the air. “I doubted whether the agreement would be ratified by the United States government,” Davis wrote. “The opinion I entertained in regard to President Johnson and his venomous Secretary of War, [Edwin] Stanton, did not permit me to expect that they would be less vindictive after a surrender of our army had been proposed than when it was regarded as a formidable body defiantly holding its position in the field.”

As expected, Johnson, following Stanton’s advice, rejected the treaty. Johnston was to surrender unconditionally or the truce would expire in 48 hours. Without further consulting Davis, Johnston agreed to the terms, not only signing over his troops in North Carolina, but also those in South Carolina, Georgia, Alabama, and Louisiana—basically all Confederate forces east of the Mississippi except for Davis and his government, whose surrender was not subject to negotiation. Quite the contrary. Stanton had telegraphed his generals that the Rebel chiefs had with them $13 million in gold plunder, which would go to anyone apprehending them.

Meanwhile, Davis had written his wife: “I have sacrificed so much for the cause of the Confederacy that I can measure my ability to make any further sacrifice required. It may be that, a devoted band of Cavalry will cling to me, and that I can force my way across the Mississippi, and if nothing can be done there which it will be proper to do, then I can go to Mexico, and have the world from which to choose a location.”

Varina replied from Abbeville. “A stand cannot be made in this country as to the trans-Mississippi,” she wrote. “I doubt if at first things will be straight, but the spirit is there.” She did not plan to wait for Northern mercy, but to escape via Florida and Bermuda or the Bahamas to England, where she might leave their eldest children in school and rendezvous with her husband in Texas.

Confederate Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton felt that Johnston had exceeded his authority in surrendering and that it would be “far better for us to fight to the extreme limits of our country rather than to reconstruct the Union upon any terms.” Some five brigades, about 3,000 fighting men, agreed. They made Davis the military commander of the largest Confederate army east of the Mississippi. “I cannot feel like a beaten man,” he said.

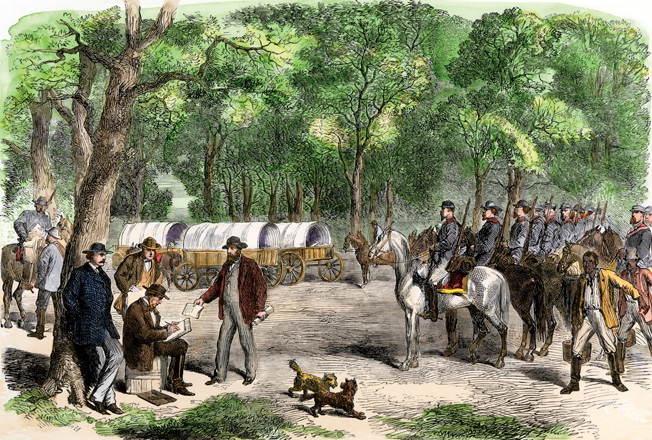

“Traveling Like a President and Not Like a Fugitive”

When the presidential party departed Charlotte on April 26 and pushed into South Carolina, they found the going slow, their progress hampered by well-wishing crowds strewing flowers in their path. Sherman’s march through central Georgia, then up the Carolina coast, had never intruded on this area of the country. Unfamiliar with the horrors wrought on their neighbors, these Southerners had nothing but admiration for Davis in his hour of retreat. “Some of the command thought we went too slow,” admitted Davis, no doubt reliving the optimistic days of 1860, when the Confederacy had repelled every Union attempt to subdue it, ultimate independence had seemed possible, and its president had led a noble uprising against oppression.

Public adulation did nothing to encourage some of his war-weary troops. “His cabinet are all against him, seeing the futility of trying to resist when throughout the South scarce a respectable body guard of organized troops can be found to protect his own person,” grumbled Confederate soldier John Dooley. “Mr. Davis believes that farther South the people will rise again and flock by thousands to his standard. Poor President, he is unwilling to see what all around him see. He cannot bring himself to believe that after four years of glorious struggle we are to be crushed into the dust of submission.”

But cavalry commander Brig. Gen. Basil W. Duke saw what his footsore troops did not: that Davis was “traveling like a president and not like a fugitive.” In those last weeks of April 1865, Davis had transcended himself from a controversial, often derided politician into a supreme symbol of Confederate resistance. By his very refusal to give up, he kept the Southern nation—at least temporarily—alive.

“All is Indeed Lost”

Elsewhere, it continued to wither. His kinsman, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, the brother of Davis’s long-deceased first wife, had opened negotiations to surrender Confederate forces in Alabama, Mississippi, and eastern Louisiana. The land route to Texas was cut off. The Confederate treasury had gotten as far as Augusta before its military escort learned of Johnston’s surrender. They brought it back to Abbeville on the Georgia border, where it was secreted in a boxcar at the train station. There, Davis called a final council of war: “It is time that we adopt some definite plan upon which the further prosecution of our struggle shall be conducted,” he said. “Three thousand brave men are enough for a nucleus around which the whole people will rally when the panic that now affects them has faded away.”

Duke remembered the meeting. “We looked at each other in amazement and with feelings a little akin to trepidation,” he recalled, “for we hardly knew how we should give expression diametrically opposed to those he had uttered.” They told Davis that to continue the war would be “a cruel injustice to the people of the South.” Davis inquired why, if they felt that way, they had come this far with him. Duke recalled, “We answered that we were desirous of affording him an opportunity of escaping the degradation of capture. We would ask our men to follow us until his safety was assured, and would risk them in battle for that purpose, but would not fire another shot in an effort to continue hostilities.” Davis had been fleeing not for his personal safety, but because he saw it as his patriotic duty. Now, at last, he saw that the Confederacy was dead. Those in the room remembered that he turned pale and, trembling, did not speak for a moment. Then he said, “All is indeed lost.”

He left the meeting. In his absence, his commanders and cabinet members devised the ways and means of dissolving the Confederacy. Remaining archives and records were to be abandoned or destroyed. The troops would be permitted to vote on whether to march on or disband. In the town streets they were already selling their uniforms and weaponry as souvenirs. It would only be a matter of time until they turned covetous eyes on the government gold. The treasury rail car was kept under armed guard, not against Union attack but against looting by their fellow Confederates. It was decided to get both the president and the treasury out of town.

With Davis at its head, the caravan rode out at 11 pm, and at dawn the president and his escort crossed the Savannah River into Georgia. The troops guarding the treasury, however, sensed the money would soon be in Union hands. Before going any farther they demanded their share on the spot. As they were not far from mutiny and looting it themselves, Secretary of War John C. Breckinridge paid out $108,000, a total of $26.25 each. “Nothing can be done with the bulk of this command,” he wrote Davis. “Many of the men have thrown away their arms. Out of nearly four thousand men present but a few hundred could be relied upon. Threats have reached me to seize the whole amount, but I hope the guard at hand will be sufficient.”

12 Hours Ahead of the Union

Around noon on May 3, Davis and his party rode into Washington, Georgia, a little town of 2,200 whose only experience of the war was a recent influx of lice-ridden ex-Confederate troops. As one resident put it, “The foot of a Federal soldier had never trodden our streets. We were a little out of the way village, in a farming country, where the hardships and deprivations of the war, for food, had never penetrated.” The irony of reaching the end of the Confederacy in a town named Washington escaped no one.

While the president and his party took much needed food and rest, Breckinridge spent the day trying to mollify the troops back at the river, many of whom were throwing away their weapons and walking off to surrender. Davis appointed Captain Micajah Clark as acting Confederate treasurer and sent him to see to final disbursal of the government funds: $230,000 to the Richmond bank officers; $86,000, secreted in a false carriage bottom, on its way to Charleston and thence the Confederate government account in London banks; and $30,000 to cover Davis’s escape.

Varina had left a note for her husband: “I dread the Yankees getting news of you so much, you are the country’s only hope, and the very best intentioned do not calculate upon a stand this side of the [Mississippi] river. Why not cut loose from your escort? Go swiftly and alone, with the exception of two or three. God keep you, my old and only love.”

His cavalry being “not strong enough to fight and too large to pass without observation,” Davis wrote back, “I can no longer rely upon them in case we should encounter the enemy. I have therefore determined to disband them and try to make my escape. We will cross the Mississippi River and join [General] Kirby Smith, where we can carry on the war forever.” The idea of reviving the South again in the West was perhaps not so farfetched. It would take Federal troops several more decades to subdue hostile Plains Indians, many of whom had made common cause with the Confederacy. How they might have fared against 40,000 Confederates is an open-ended question.

As a diversion, Davis sent Breckinridge off with the bulk of the remaining cavalry. Former naval officer Colonel Charles Thorburn mapped a route to the east coast of Florida, where he had a boat hidden on the Indian River. From there Davis might sail around the peninsula and across the Gulf of Mexico to Texas. Davis rode out with just 10 picked men, one wagon, and two ambulances. Union cavalry rode into town 12 hours behind them.

In a few days Davis closed to within 20 miles of Varina’s party, only to learn that a band of ex-Confederate marauders was on her trail. “I do not feel that you are bound to go with me,” he told his men, “but I must protect my family.” They rode so hard that several were left behind when their horses gave out. Outside Dublin, Georgia, Davis and the remainder spotted a small circle of wagons. A sentry called, “Who goes there?” and Davis recognized the voice of his secretary, Burton Harrison, who had escorted Varina and the children all the way from Richmond.

“Well, Old Jeff, We’ve Got You at Last”

The happy reunion was short lived. Union forces were tightening the net. The Johnson administration had announced a $100,000 reward for Davis’s capture. By May 9, Lt. Col. Henry Harnden’s 150-man 1st Wisconsin Cavalry, linking up with Lt. Col. Benjamin D. Pritchard’s 400-man 4th Michigan Cavalry in Abbeville, learned the Davis wagon train was just hours ahead, headed for Irwinville. That evening they split up again to search it out and, unknown to each other, converged on it from two different directions.

A drizzle had settled over the night. Just before dawn the Confederates heard horses milling out in the misty dark. Abrupt shots rang out from two directions. Bullets hummed around the camp. Davis told Varina, “The Federal cavalry are upon us.”

Pritchard rode into camp, shouting for the Federal troopers to cease fire. They lost two dead and four wounded from friendly fire; no Southerner had so much as fired a shot. Davis took advantage of the confusion to try a getaway. Whether he grabbed his wife’s cloak in his haste, or she threw it over him as cover, depends on who tells the tale. For the rest of his life Davis would be hounded by the story that he had tried to escape disguised as a woman. He was making for the nearest woods when a trooper called on him to halt. Varina threw her arms over her husband, pleading for his life. “Shoot me if you wish,” she cried defiantly. The Union trooper was unmoved. “I wouldn’t mind a bit,” he said. About that time Pritchard rode up, saying, “Well, old Jeff, we’ve got you at last.”

Word immediately spread that the Confederate president had been captured in his wife’s clothes. “Jeff Davis Captured in Hoop Skirts” and “Jeff Davis in Petticoats” were two of the headlines in Northern newspapers. Cartoonists drew laughter for months with drawings of an effeminate-looking Davis mincing about in a shawl and dress. At least one of the Union soldiers on hand that day, Captain James H. Parker, went out of his way to shoot down the absurd story. “I defy any person to find a single officer or soldier who was present at the capture who will say upon his honor that he was disguised in women’s clothes. Hi wife behaved like a lady, and he as a gentleman, though manifestly chagrined at being taken into custody. I am a Yankee, full of Yankee prejudices, but I think it wicked to lie about him.” Still the story endured.

Reconciliation After the War

Taking their prisoner to Macon, Davis’s captors taunted passing Confederates, “Hey, Johnny Reb, we’ve got your President.” One defiant onlooker responded, “Yes, and the devil’s got yours.” Other paroled soldiers were less forgiving. Told by the Federals, “We’ve got your old boss back here in the ambulance,” the men replied bitterly, “Hang him! Shoot him! We’ve got no use for him. The damned Mississippi Mule got us into this scrape.” His apotheosis as a Southern martyr was not yet underway.

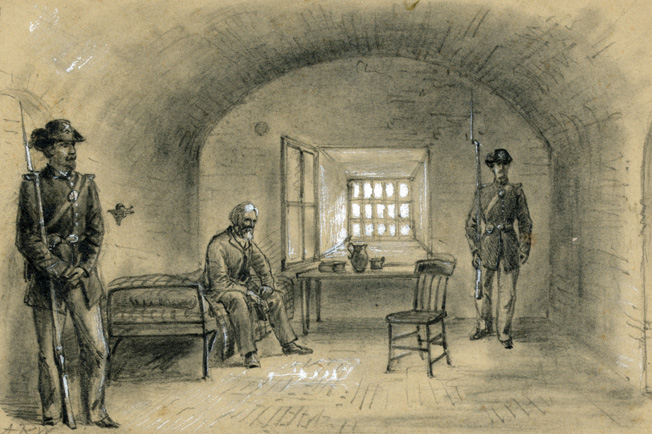

Within days Davis was bound for Fort Monroe, at the southernmost tip of Virginia’s York-James peninsula. “Try not to weep,” he told Varina as his captors marched him within the building. “They will gloat over your grief.” Inside the fortress walls, 30 feet high and 100 feet thick, a subterranean gunroom had been converted into a cell especially for the leader of the rebellion. Davis was locked into heavy manacles. The dank chamber was lit around the clock. His guards were changed every two hours. With no sun, little sleep, and his chains wearing him down, Davis’s health declined.

The Johnson administration couldn’t decide what to do with him. Trying ex-Confederate leaders for treason would do nothing for reconciliation. Northern sympathizers and even Pope Pius IX championed Davis’s freedom. After two years, Johnson, falling out with Stanton and facing (ultimately successful) threats of impeachment, didn’t need the continuing headache. Davis was simply released on bond. He and his family moved to Canada, Cuba, and Europe before settling in Mississippi. His massive two-volume history of the war, The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government, went a long way to establishing Davis’s reputation, for better or worse, as a leader and icon of the South’s Lost Cause, a term he coined first. “When the cause was lost, what cause was it?” Davis wrote. “Not that of the South only, but the cause of constitutional government, of the supremacy of law, and the natural rights of man.” It was, perhaps, the best face he could put on a ruinous war of choice that had cost the lives of more than 600,000 Americans, left the South destitute, and destroyed his own reputation as a political statesman.

I just loved reading this part of history. I’m going to continue reading more. What happens to people and their relations after world events is rarely publicized. Thank you so very much for publishing parts of history.

Carole Woodward.

(Age 83)

I thought this was a work of great scholarship. As a native of Charleston SC, I am So fascinated by the history that molded us. You have handled the “clay ” with artful care,detail,and respect.

“By May 10th Richmond had fell, it was a time I remember oh so well….”