By David A. Norris

Sergeant Joseph Plumb Martin, a sapper in the Continental Army, waited for the signal that would begin the night attack on two enemy-held redoubts. He was so anxious that when he saw the bright planets Venus and Jupiter shining high above, he was ready to spring to his feet, thinking they were the signal.

Martin and his advance party were waiting to start hacking through the obstructions protecting the British outworks. Hundreds of French and American troops would then capture the redoubts. And if the redoubts were taken, the siege against the army of Lt. Gen. Earl Charles Cornwallis in Yorktown, Virginia, would gather momentum.

Only a few weeks before, the American cause had been teetering on the edge of failure, mired in setbacks and frustration. Now, General George Washington’s Continental Army was on the verge of potential victory by capturing the largest British field army in North America.

The American Revolutionary War had reached a stalemate in the northern colonies by 1778. The British controlled New York City and Philadelphia, but while Redcoat armies made constant forays into the countryside, they could only permanently hold on to heavily fortified bases that could be resupplied by sea. Even worse, France joined with the Continental government against Britain in 1778.

Lord George Germain, the British secretary of state for the colonies, decided to try a new approach. He sacked Maj. Gen. William Howe, replacing him with Maj. Gen. Sir Henry Clinton as army commander-in-chief for North America. Clinton abandoned Philadelphia and held New York, and from then on, British military strategy focused primarily on the southern colonies. The hope was that thousands of southern loyalists would flock to the king’s standard when they saw British regulars arrive, enabling Crown forces to finally crush the Continental Army and patriot militias.

The port of Charleston, South Carolina, fell to Clinton’s forces on May 12, 1780. Returning to New York, he left Earl Charles Cornwallis in command of the Army in the South. Cornwallis marched deep into the Carolinas in the fall of 1780. Some loyalists rallied to the king, but the royal cause suffered disastrous setbacks at King’s Mountain on October 7, 1780, and Cowpens on January 17, 1781.

Cornwallis entered North Carolina, where he pursued Continental commander Maj. Gen. Nathanael Greene until their armies clashed at the Battle of Guilford Courthouse on March 15, 1781. After a fight that ended in hand-to-hand combat, Greene pulled his troops from the field; however, British losses were so great that continued operations so deep inland were deemed to be too dangerous.

The battered British Army then marched southeast to Wilmington, North Carolina, a port that the British had seized as a supply base at the end of January 1781. Rather than continue a frustrating campaign in the interior of the Carolinas, Cornwallis marched for Virginia on April 25, 1781. Cornwallis hoped to establish a base in Virginia that would accommodate reinforcement and resupply by sea. The British reached the Virginia border on May 10; three days later, Major General William Phillips, the British commander in Virginia, died of typhoid, and Cornwallis took his place.

Late in 1780, General Sir Henry Clinton had sent 1,600 troops under Brig. Gen. Benedict Arnold to Virginia to support Cornwallis’ southern campaign. Arnold captured and burned Richmond (which replaced Williamsburg as Virginia’s capital in 1780) on January 5, 1781. He then withdrew to Portsmouth on the Chesapeake Bay.

To counter Arnold, Washington sent his trusted associate Maj. Gen. Marie Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier, the Marquis de Lafayette, to Virginia in February 1781. He joined forces with troops already present under Baron Friedrich von Steuben. By summer, the American force in Virginia grew to 4,000 regulars and militia.

After successfully raiding Charlottesville on June 4 and repulsing a July 6 attack by Lafayette at Green Spring, Virginia, Cornwallis followed new orders to establish a permanent base at Yorktown, 13 miles east of Williamsburg.

The county seat of York County, Yorktown had roughly 200 houses. Warehouses, wharves, taverns, and cheap lodgings were clustered along the shore of the York River. Higher up on a bluff overlooking the river, the rest of the town, including the church, courthouse, and some fine mansions, was centered along Main Street and half a dozen side streets. Yorktown’s location on the deep, wide York River offered easy access to the sea and a sizeable harbor for seagoing ships.

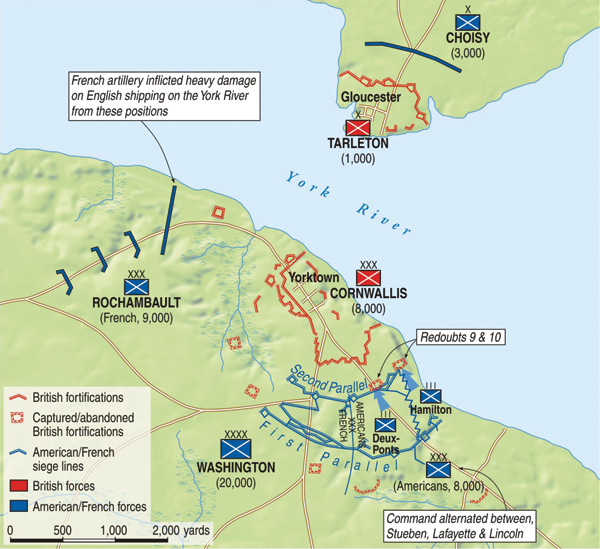

The British reached Yorktown on August 2. After absorbing the garrison of Portsmouth, Cornwallis now had more than 7,000 soldiers. His Brigade of Guards, an ad hoc unit assembled specifically for the “American War,” drew from the best soldiers in the elite Guards regiments. Besides various small Redcoat units, there were seven British foot regiments. Also on hand were 500 cavalry (mostly American provincial regulars) in Lt. Col. Banastre Tarleton’s British Legion and Colonel John Grave Simcoe’s Queen’s Rangers. There were three German regiments, the large two-battalion Ansbach-Bayreuth Regiment and two regiments from Hesse-Kassel, as well as artillerists and a company of jägers, crack riflemen skilled in woodland fighting. Also present were some American loyalists and a detachment from the Royal Artillery.

Tarleton’s cavalry were among the troops sent across the York River to Gloucester Point on the north bank, which occupied the tip of a small cape that jutted into the river. The York River here was about 2,000 feet wide, considerably narrower than any other stretch for about 20 miles upstream.

The Continental Army under General George Washington was far to the north along the Hudson River, well upstream from the British in New York City. On July 7, 4,800 French troops under Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, Comte de Rochambeau, joined Washington after marching from Rhode Island.

Bolstered by the French troops, Washington favored driving the British out of New York. Rochambeau, who tactfully disagreed with his ally, thought New York was too heavily defended for a successful attack. Cornwallis’ army in Virginia was a more attractive target. Newly arrived, they had not had time to dig in as strongly as the garrison at New York. Also, if the sea could bring reinforcements to Cornwallis in Virginia, the sea could also bring French King Louis XVI’s ships and soldiers.

Rochambeau knew that French Admiral Francois Joseph Paul, Comte de Grasse, had arrived in the Caribbean in April with 23 ships. De Grasse was under orders to cooperate with the Continentals against the British. Rochambeau wrote de Grasse, asking that he sail his fleet either to New York or to Virginia with any troops he could bring and money to relieve the plight of the near-bankrupt Continental cause.

The admiral was in San Domingue (modern-day Haiti) when Rochambeau’s letter reached him. Agreeing to Rochambeau’s plans, de Grasse obtained 3,300 troops and some artillery under the command of Maj. Gen. Claude Henri de Rouvroy, Comte de Saint-Simon, from the governor of San Domingue. No amount of pleading or begging could pry away any of the badly needed money for the American rebels, though. Finally, de Grasse got 1.2 million livres from the colonial Spanish government of Cuba and wealthy sympathizers in Havana.

De Grasse sailed on August 5, heading for the closer of his two options, which was Virginia. Washington soon learned that Cornwallis had moved to Yorktown, and on August 14, news arrived that de Grasse was on his way to the Chesapeake Bay.

With de Grasse on the move, Washington started his army on the 400-mile march southward to Virginia on August 19. Plans were kept as secret as possible. The Continental rank-and-file were unsure where they were going, but for a few days, they and the French managed to make Sir Henry Clinton believe they were positioning themselves to attack New York City.

break the French cordon at sea.

Rochambeau’s siege guns had been left in Rhode Island. They were loaded aboard a small fleet under Admiral Louis Jacques, Comte de Barras, whose eight ships left Newport bound for Virginia on August 25.

Meanwhile, British Admiral Samuel Hood set off in pursuit of de Grasse with 14 ships, reaching the Chesapeake on August 25 without seeing the French fleet. De Grasse’s route, through Bahama Channel, made for a longer voyage, but it allowed him to avoid detection. Hood then decided to sail to New York.

On August 31, De Grasse arrived and delivered Saint-Simon’s troops. Cornwallis observed the French soldiers being ferried up the James River on September 2, escorted by French frigates. The soldiers came ashore at Jamestown. The combined Franco-American force now occupied the York Peninsula up to Williamsburg, hemming Cornwallis in at Yorktown. The first Continentals and French marched through Philadelphia on September 2, and small French ships sailed as far as Head of Elk—at the northeastern tip of the Chesapeake—to pick up Allied troops when they arrived in Maryland.

Hood had notified Admiral Thomas Graves, commander of the Royal Navy in North America, that de Grasse was sailing to Virginia. Graves also knew of Barras’ departure from Rhode Island. With Graves in command, he and Hood assembled 19 ships and sailed for Virginia on August 31.

British sappers worked on fortifications at Yorktown. They pulled down many houses in town to create a clear field of fire and to provide planks and beams for their works. Soon the entrenchments surrounded an area 1,500 yards wide and 500 yards deep. A protruding section known as the Hornwork protected Hampton Road. Scattered outside the main works were 10 redoubts.

Graves’ arrival off Cape Henry on September 5 caught de Grasse completely by surprise, as hundreds of his sailors were ashore bringing fresh water to the fleet. The French struggled to form a line of battle, but Graves moved slowly and did not take advantage of his enemy’s disarray. It was shortly after 4 PM when the fleets came within firing range of each other off Cape Henry and Cape Charles.

In the Battle of the Virginia Capes, fought on September 5, six French captains were killed and four of de Grasse’s ships were put out of action. De Grasse’s losses came to 230 dead and wounded. Graves’ casualties came to approximately 350 men, and six of his ships could no longer fight without repairs. No ships were sunk; however, the 74-gun Terrible was so badly damaged that she had to be scuttled.

Neither admiral pushed to resume combat. After several days, de Grasse turned back to the Chesapeake. By the time Graves was ready to renew the clash, Barras’ ships had arrived, bringing the French fleet to 36 ships. Because it was outnumbered nearly 2-to-1, the British fleet returned to New York.

Compared to other fleet actions, the Battle of the Virginia Capes was a minor one in terms of losses, but it had a massive influence upon American history, as it ended Cornwallis’ hopes of receiving more troops and supplies by sea. The French Navy had bottled up Cornwallis and his vessels in the Chesapeake and sealed the bay to prevent any more British help from getting through.

As the Continentals and the French traveled by boat or by foot toward Yorktown, Washington arrived at Mount Vernon on the south bank of the Potomac River on September 9. It was the first time he had seen his home since leaving to take command of the Continental Army outside Boston six years before, in the summer of 1775.

Washington and Rochambeau rode into Williamsburg, where they joined Lafayette on September 14. Washington took command of the combined forces. It took several days for army and naval commanders to plan the strategy for the siege that would be necessary to take Yorktown.

On September 28, Washington’s army marched to Yorktown to begin the siege. After fending off probes by French troops, Cornwallis fell back from his outer lines shortly after midnight, abandoning four redoubts in front of his center. His army squeezed inside the inner fortifications along with the remaining civilians of Yorktown; the British were truly trapped. Communication with Clinton and Graves in New York was possible only by sending dispatches in whaleboats. Anything larger was liable to be spotted and snapped up by the French Navy or an American privateer.

Abandoning the outworks was a calculated risk, but the available troops could better defend the smaller inner perimeter. Earlier that day, a dispatch arrived from New York by whaleboat, revealing that Clinton planned to sail with 23 ships and 5,000 more troops on October 5, convincing Cornwallis that he only needed to hold on for another week at most.

Washington would be undertaking a formal siege of Yorktown, which would be a new approach for him in the long war. Few in the Continental Army had more than a theoretical acquaintance with siege warfare. Fortunately, their French allies had plenty of experience. Soldiers set about the preliminary work of filling sandbags and making gabions (huge wicker baskets that could be filled with dirt for quick construction of field works) and fascines (bundles of saplings covered with dirt used in building up earthworks).

Gloucester Point, just across the river and held by Tarleton, offered a possible escape route for Cornwallis. Five redoubts and a line of works shielded the British camp there.

Brigadier General George Weedon’s 1,500 militiamen held Tarleton’s force in place. Armand Louis de Gontaut, Duc de Lauzun, brought his 600-man legion of foot and cavalry on September 28. At Lauzun’s request, Rochambeau sent some artillery and 800 marines to Gloucester. General Claude Gabriel, Marquis de Choisy, was placed in overall command.

Choisy attacked the British at Gloucester on October 3 with Lauzon’s Legion and Weedon’s militia. Most of the Redcoats were out foraging, loading wagons and packhorses with stolen corn. Tarleton and Lauzun spotted each other on the battlefield. They intended a personal duel until Tarleton’s horse fell and threw the major to the ground. Lauzun galloped ahead to capture Tarleton, but a handful of dragoons rescued him. The French duke had to be content with taking Tarleton’s horse, but in the course of the skirmish, his men killed or wounded 50 of Tarleton’s troopers.

Choisy now pitched a new camp on the battlefield, where he posted a strong picket line, and from then on, the British were penned in at Gloucester. American surgeon James Thatcher witnessed the grim result of the cavalry clash. “The enemy from want of forage are killing off their horses in great numbers. Six or seven hundred of these valuable animals have been killed, and their carcases [sic] are almost continually floating down the river,” he wrote.

British guns in Yorktown fired on French and Continental troops as they began the preliminary work on their siege lines. Construction started on October 6 with the first parallel, a 2,000-yard line that mirrored the British works 800 yards away. Engineers had previously driven in a line of stakes to guide the workers. Fifteen hundred men carrying fascines and entrenching tools quietly marched to their starting points and went to work, guarded by nearly twice as many with muskets at the ready. French troops worked on the left half, and Americans handled the right, which ended near the York River.

After daylight, the guns in Yorktown opened fire on the parallel. Sergeant Martin saw a bulldog run out of the British lines several times to chase some of the cannon balls. There was some thought of catching the British bulldog and tying a mocking note around his neck to take back to his masters, but “he looked too formidable for any of us to encounter,” wrote Martin. Allied siege batteries were not ready, so the sappers had to keep working and endure the fire as best they could.

The same day that work began on the first parallel, Washington’s close friend and invaluable officer Colonel Alexander Scammell, commander of the light infantry, led a small reconnaissance force towards British lines. British dragoons rode out from a patch of woods and quickly captured Scammell. While one horseman took Scammell’s reins, another of Tarleton’s men shot the colonel in the back. Scammell was returned under a flag of truce, but he died shortly after.

With the preliminary work on the first parallel finished by dawn on October 7, construction on the batteries continued over two more nights before the artillery was ready to open fire on the afternoon of October 9. A French battery was the first to open fire on the extreme left of the parallel. Twelve guns—18- and 24-pounders, howitzers, and mortars—lobbed shot and shell toward Yorktown. One of their first shots plunged into a house where officers of the 76th Foot were having dinner. The shot wounded several officers and killed Commissary General Perkins. Perkins’ wife, who had been sitting between her husband and the wounded officers, escaped unharmed. A shot striking a different house killed the sutler (provisioning merchant) of a German regiment.

Two hours after the French opened fire, Washington fired the first shot from the American battery on the right of the parallel. This American battery had six 18- and 24-pounders, two howitzers, and a pair of mortars.

The following day, four newly deployed Allied batteries opened fire. Placed as they were, the 50 heavy guns of the French and American artillery enfiladed the longest face of the Yorktown fortifications. The bombardment battered the embrasures of the British artillery and dismounted one Yorktown gun after another. “[On] the 10th, scarcely a gun could be fired from our works, fascines, stockade platforms, and earth, with guns and gun-carriages being all pounded together into a mass,” wrote Captain Samuel Graham of the 76th Foot.

Lieutenant Colonel St. George Tucker noted that the British gunners found a way to harass their enemies while conserving their dwindling supply of projectiles: Gunners touched off a bit of gunpowder near their cannon muzzles, which would make the Continentals or French abandon their duties and take cover.

American surgeon James Thatcher watched the bombardment with fascination. “The bomb shells from the besiegers and the besieged are incessantly crossing each other’s path in the air,” he wrote. “They are clearly visible in the form of a black ball in the day, but in the night, they appear like a fiery meteor with a blazing tail…I have more than once witnessed fragments of the mangled bodies and limbs of the British soldiers thrown into the air by the bursting of our shells.”

The French artillerists fired up a shot furnace on October 10. After dark, three red-hot glowing rounds plunged into the unfortunate frigate Charon. One of these shots ignited the sail locker. The ship’s skeleton crew could not control the soaring flames and was forced to abandon ship without having time to scuttle the doomed vessel. Soon adrift and still ablaze, the Charoninexorably edged toward a transport, which also caught fire.

“The ships were enwrapped in a torrent of fire, which spread with vivid brightness among the combustible rigging and ran with amazing rapidity to the tops of several masts, while all around was thunder and lightning from our numerous cannon and mortars, and in the darkness of night, presented one of the most sublime and magnificent spectacles which can be imagined,” wrote Thatcher.

Two more French batteries, with nine 24-pounders, heaved even more metal into the enemy works on October 11. Heated French shot set two more British transports on fire. Very few buildings in Yorktown escaped serious damage, if not complete ruin or fire. Cornwallis and his staff huddled in a grotto in the garden of Thomas Nelson, governor of Virginia at the time of the siege, and a general of militia. Many civilians and soldiers sheltered in caves dug under the bluff by the river. “Officers looked not only sad, but ashamed,” observed an American sutler after the siege. “They had lived under the ground like ground hogs.”

Work began on the second parallel, but two British works, Redoubt 9 and Redoubt 10, blocked its projected path. Both redoubts, which were spaced 300 yards apart, were protected by abatis. This was a tangled barrier of felled trees with the sharpened points of branches sticking outward like pikes.

Washington planned to take the redoubts on the night of October 14. Saint-Simon would make a feint against the redoubt on the extreme right of the British works, which was manned by 120 men from the 23rd Regiment of Foot (Royal Welch Fusiliers) and Marines from the naval vessels in the river. Another feint would be aimed at the British across the river at Gloucester.

The attack against Redoubt 9 would be made by 400 French troops under Baron de Viomenil, the French second-in-command. Colonel Alexander Hamilton would lead 400 Continentals in a simultaneous assault on Redoubt 10. Rather than risk alerting the British with a stray shot, Hamilton’s men would attack with bayonets fixed on unloaded muskets.

Sergeant Martin was part of the detachment sent ahead to chop a path through the abatis before Redoubt 10. After dark, Martin and his comrades saw the signal to advance. This consisted of “three shells with their fiery trains mounting the air in quick succession,” he said. They pressed on quietly but were spotted by the British when they reached the abatis.

“We were now at a place where many of our large shells had burst in the ground, making holes sufficient to bury an ox in. The men having their eyes fixed upon what was transacting before them, were every now and then falling into these holes,” he wrote. “I thought the British were killing us off at a great rate. At length, one of the holes happened to pick me up, I found out the mystery of the huge slaughter.”

Hacking their way through the abatis was painstaking work. Some of Hamilton’s more impatient men pushed and squeezed through the barrier without waiting for sappers to cut them a clear path. Once through the abatis, a sturdy log palisade protected the redoubt. Fortunately, the bombardment had smashed a few gaps in the palisade. A few soldiers passed through the gaps and reached the ditch at the base of the redoubt’s wall.

Major James Campbell commanded 60 British and German soldiers in the redoubt. They emptied their muskets into the charging Continentals and dropped grenades on the soldiers in the ditch below.

Following their leader, a few of Hamilton’s men pushed through the trench at the foot of the enemy works and climbed up the walls. More soldiers poured in for the final rush, some of them stopping to load their muskets.

When Campbell realized a group of 80 men led by Lt. Col. John Laurens was coming from behind them, he surrendered. In the violent five-minute clash, nine Americans had been killed and 25 wounded. Eight of Campbell’s men were killed or wounded, seventeen men were captured, and the rest escaped into the night.

Redoubt 9 was in the hands of 120 Hessians of the Regiment de Bose. De Viomenil’s soldiers waited until their sappers had cut through the abatis before rushing to the parapet. Under heavy fire for some time, they suffered 46 dead and 68 wounded. Two sergeants so distinguished themselves that de Viomenil later invited the two to dine with him, with the non-commissioned officers seated at the right hand of the baron.

After losing the two redoubts, the British retaliated on the next night. Lieutenant Colonel Robert Abercrombie sent 350 of the finest soldiers of the garrison in two detachments to assault the Allied siege line and spike some of the siege guns.

Lieutenant Colonel Gerard Lake led the Guards Brigade and the grenadier company of the 80th Foot against 50 soldiers of the Agenais Regiment in a French battery near the center of the Allied works. Most of the defenders were asleep. In moments, the Redcoats bayoneted an officer and a dozen men and scattered the rest. Meanwhile, Major Thomas Armstrong led the light infantry brigade into an adjacent American gun battery, taking a force of Continentals and Virginia militia by surprise. Some of the defenders engaged in hand-to-hand combat as others fled.

With the Allied batteries in British hands, the redcoats spiked 11 heavy guns. Their time limited, they resorted to the quick method of jamming bayonets in to the touch holes and breaking off the blades. They had only a few minutes to work. Out of the dark came shouts of “Vive le Roi!” French grenadiers commanded by the Viscomte de Noailles poured into the battery and drove the British out at bayonet point.

Lake and Armstrong had pulled off an impressive feat, but to little avail. Truly spiked guns were difficult to repair, but artificers managed to remove the broken bayonets and have the guns ready to resume firing before noon the next day.

By the end of the siege, the Allies had fired 15,737 artillery rounds at the British in Yorktown. Some slaves who took refuge with the British labored at filling in the scores of shell craters. On occasion, an explosive shell would hit hard ground and not bury itself in the earth. Redcoats who dashed forward and prevented the blast by breaking off the fuse received a reward of one shilling, a risk many men readily undertook intending to use the reward money to buy extra spirits.

Cornwallis’ fortifications crumbled as more and more of his guns fell mute under the ceaseless enemy bombardment. Realizing that his position was quickly deteriorating, the earl took one last gamble on an attempted breakout, preparing 16 large boats to ferry his troops across the river to Gloucester on the night of October 16-17. Sick and wounded soldiers would be left behind in the care of Washington and the French. With the Yorktown troops united with Tarleton at Gloucester, the British would outnumber the surrounding Allied forces. Simcoe would get around Lauzun and hit from the rear, while the others attacked his front. Overwhelming Lauzun’s cavalry would provide a few hundred badly needed horses. Once out of the trap at Yorktown, Cornwallis could maneuver freely and carry on the war.

The Light Infantry, most of the Guards, and part of the 23rd Regiment boarded the boats at 10 PM. They disembarked at Gloucester Point, and the boats returned to Yorktown to reload. Once the boats headed for Gloucester a second time, though, a violent thunderstorm descended upon them. The heavy winds lashed the river and drove all the boats downstream. Two boats were pushed so far downriver that a French frigate captured them.

When the sun rose, some of the boats had landed downstream from Yorktown, but a few were still out in the river. French and American guns zeroed in on the river opened fire on the boats, causing some casualties.

With the collapse of the evacuation, the British were even worse off than they had been before, with their army now hopelessly split in two. At mid-morning, a drummer boy appeared atop the parapet of the Yorktown works. An officer waving a white handkerchief walked toward the Allied lines, accompanied by the drummer. The officer carried a letter that Cornwallis had written after dawn, proposing a truce while two officers from each side worked out terms for the surrender of Yorktown. It was October 17, 1781, four years to the day after the British had suffered another shock, the surrender of General John Burgoyne’s army at Saratoga, New York.

Graves had hoped to sail from New York on October 12, but a storm had battered the fleet, causing some delays for repairing masts and rigging. They did not start for Virginia until October 17, the same day Cornwallis sent his first surrender proposals. Two days later, when all the ships had cleared Sandy Hook for the open sea, it was already too late.

As negotiations began, Cornwallis wanted his men to be paroled. The very idea of such leniency angered the Americans, who resented the harsh treatment and atrocities inflicted on prisoners captured at Charleston the year before. Most of the British troops would be sent to prison camps. American loyalists would be treated as prisoners of war, but deserters from the Continental Army or American militias found with the British would be hanged.

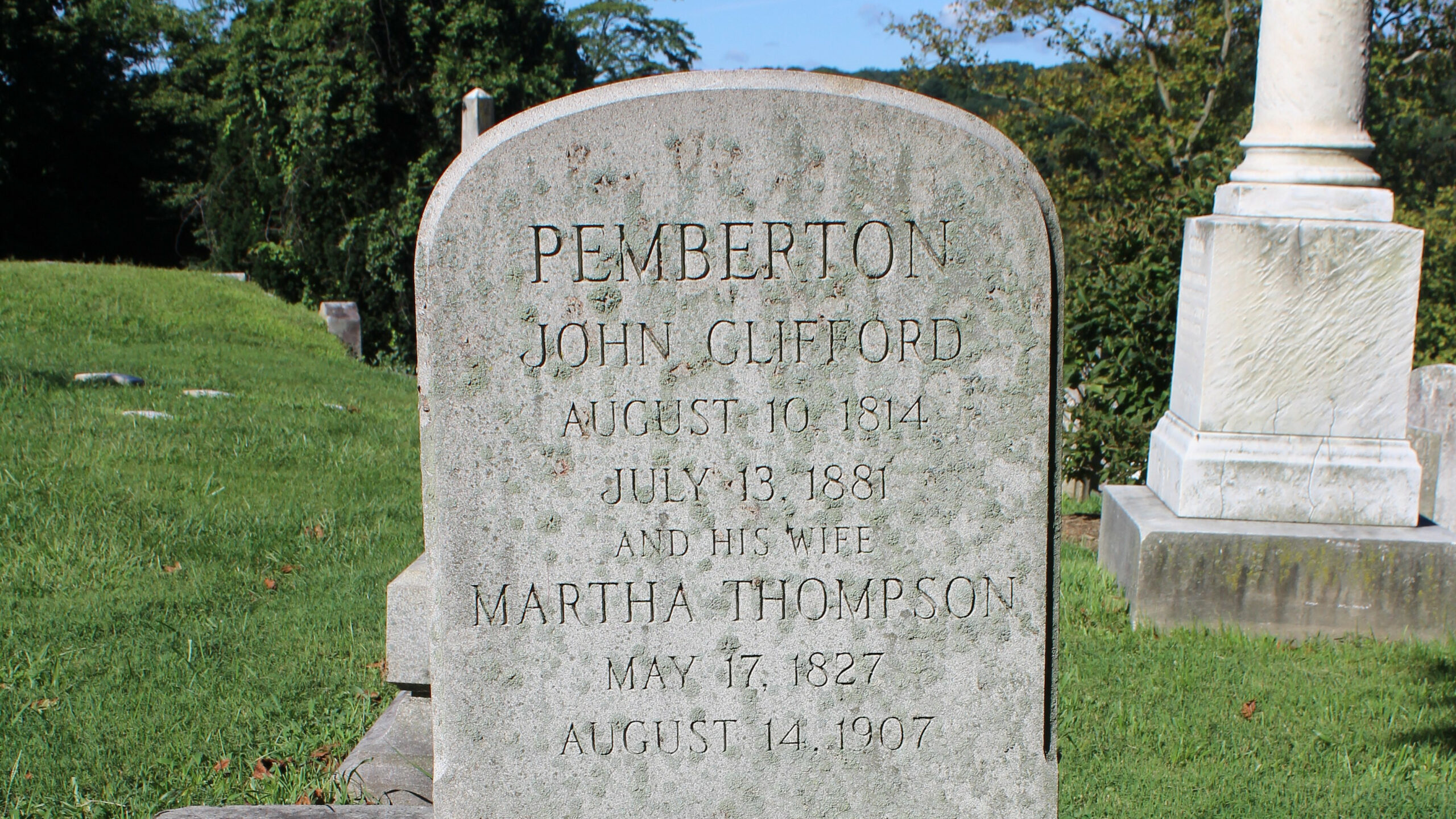

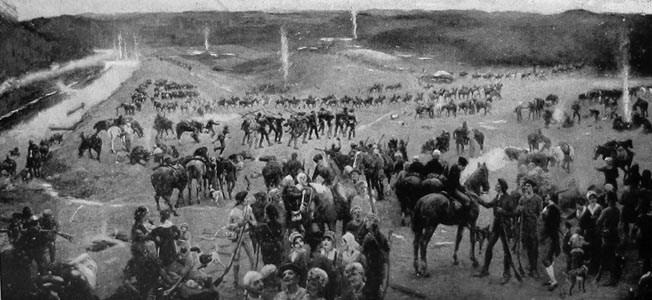

On October 19, the day set for the surrender ceremonies, Cornwallis professed he was ill and did not appear. The humiliating task of surrendering the British Army fell to Maj. Gen. Charles O’Hara. He carried Cornwallis’ sword, which he tried to present to Washington. As the British second-in-command was holding the sword, Washington had O’Hara hand it to Benjamin Lincoln, the Continentals’ second-in-command. Lincoln immediately returned the sword.

The Americans took into captivity 7,247 army officers and men (more than one-quarter of whom were Germans), as well as 840 naval personnel and 80 camp followers. Dozens of flags, including 73 camp colors and 24 regimental standards, were handed over to the Americans.

The British and German troops marched with cased colors to the field south of Yorktown, where they laid down their firearms. A smaller ceremony unfolded across the river, where Tarleton and Simcoe’s cavalry grounded their firearms. Tucker reported the surrender of 300 of their horses.

In addition to 7,794 muskets, 244 pieces of iron and brass artillery also fell into Continental hands. Additionally, the Continental Army took possession of vast amounts of ammunition and army equipment, 20 iron and brass blunderbusses, 602 grenades, and 46 halberds.

During the siege, the Americans lost 27 dead and 73 wounded, while French losses were even higher: 50 dead and 127 wounded.

The British lost more: 156 killed, 326 wounded, and 70 missing. Interestingly, only one British field officer was killed during the campaign, Cornwallis’ aide Major Charles Cochrane. While inspecting his battered works accompanied by Cochrane a few days after the fighting at Redoubts 9 and 10, the earl invited the major to fire off one of the field pieces. After firing the gun, Cochrane peered over the parapet in order to see the effect of his shot. Just at that moment, an incoming shot from American lines decapitated Cochrane, killing him instantly.

Two days after the surrender, the British prisoners started marching under militia guard to captivity at internment camps at Winchester, Virginia; Frederick, Maryland; and Lancaster, Pennsylvania. Officers still retained their swords; however, witnesses in Williamsburg noted a change in appearance. “The British officers don’t look as saucy as they did,” the people were heard to say. Cornwallis, who would escape long captivity, gave his parole not to engage in further hostilities on October 28. On that day, Graves and Clinton appeared off the Virginia capes with 5,000 fresh troops and every ship of the line the Royal Navy could assemble. They were far too late, and the great fleet returned to New York.

It took a month for the news to reach England, where it burst like a bombshell in Parliament and the press. “Oh God, it is all over,” exclaimed Lord Frederick North, the British prime minister. Like the war effort in America, the government collapsed; Germain resigned in February 1782, followed by North the following month.

But the curtain had not quite fallen on the Revolutionary War just yet. Crown forces still held New York and Charleston. Desperate loyalist irregulars carried on a devastating guerilla war in contested regions of the interior. Privateers still prowled the seas, snapping up merchant ships.

All the same, there was no support in Britain for raising a new army to turn the tide in North America. In March 1782, Parliament passed a resolution to end the war, its cost having become greater than the value of keeping the rebellious colonies in the British Empire. Diplomats hammered out the Treaty of Paris and signed it on September 3, 1783, followed by its ratification by the Continental Congress on January 4, 1784.

This formally confirmed what everyone already knew: The War for Independence had come to a conclusion at Yorktown as a result of the sound tactics of Washington and his French allies.