By Robert L. Durham

Twenty-six year-old Napoleon Bonaparte took command of France’s 23,000-strong Army of Italy in Nice, France, in late March 1796. It was almost a full year before the Battle of Rivoli, but even then, some of the officers in the French army found Napoleon’s appearance and demeanor sorely wanting.

“Owing to his thinness his features were almost ugly in their sharpness,” wrote Count Yorck von Wurtenburg. “In spite of his apparent bodily weakness, he was tough and sinewy under his sallow face.”

Despite all of this, Wurtenburg concluded by observing that Bonaparte’s grayish-blue eyes were those of a genius. His eyes alone commanded respect. Before his piercing eyes “all bowed low,” wrote Wurtenburg.

In a conference with his generals on March 27, Bonaparte skipped over the pleasantries that another commanding general might have deemed appropriate and asked pointed questions about the condition of the army. He questioned each of his generals on the positions of their respective divisions, the spirit of the men, and the effective force of each division. He then disclosed his plans for the upcoming campaign. He was disappointed when he found out that they had not been paid or outfitted in a long time.

Next, the new commander-in-chief reviewed his troops. He was shocked to see their condition. The uniforms of both officers and men were torn in places and threadbare. Some wore shoes, some wore boots, and some went barefoot. Some wore helmets, and others wore caps.

“Soldiers! You are hungry and naked; the government owes you much, but can give you nothing, “ he told them. “I will lead you into the most fertile plains on earth. Rich provinces, opulent towns, all shall be at your disposal. You will find honor, glory, and riches.”

Napoleon hoped by his speech to light a fire in their bellies. Afterwards, he fired off a dispatch to the Directory, the five-man committee that ruled France for four years beginning in November 1795. “I found this army, not only destitute of everything, but without discipline,” he said. Bonaparte wasted no time getting them a portion of their back pay and new uniforms.

Napoleon’s Ace in the Hole: His Trio of Generals

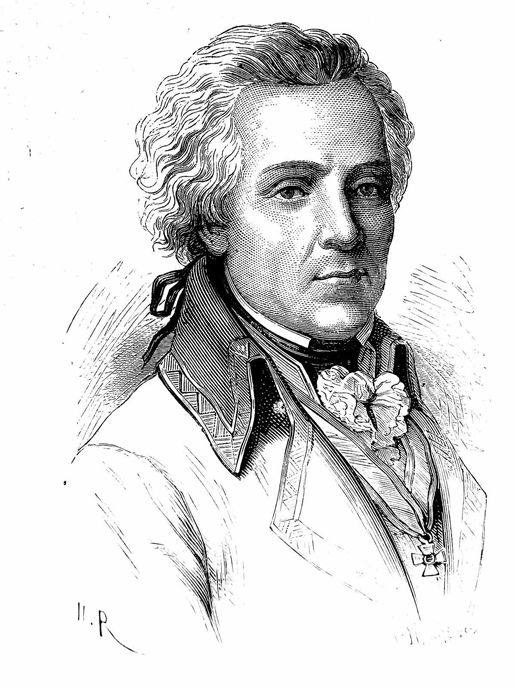

If his troops left a lot to be desired, Napoleon had a solid trio of generals serving as division commanders. The first of the three, Jean Serurier, had seen 34 years’ service in the Royal Army before the Revolution. The oldest of the three, he had fought in the Seven Years’ War and the Spanish-Portuguese War. Although he was a harsh disciplinarian, lacking in imagination, he was a methodical worker. Napoleon could count on him to follow his orders.

The second general, General Pierre Augereau, was the son of a Parisian servant. A soldier of fortune, he started his military career in the French Royal Cavalry. He soon had to flee after killing an officer. Next, he fought in the Russian Army against the Turks. After that, he became one of the famous Potsdam guards in Frederick the Great’s army.

Following a series of adventures in Greece, Italy, and Portugal, Augereau returned to France in 1792 and enlisted in the Revolutionary Army. Within a year’s time, he was promoted to division command. He was a gifted tactician who was adored by his soldiers. Augereau was “a kind of coarse and uncultured Ajax, intrepid and boastful, proud of his tall stature, of his martial figure and his valour,” said fellow general Count Philippe-Paul de Segur. Bonaparte concurred. “He has plenty of character, courage, firmness, activity; is inured to war; is well liked by the soldiery; is fortunate in his operations.”

The third of Bonaparte’s experienced division commanders was Andre Massena. A native of Nice, Massena had served as a sergeant major before leaving the French army in 1789. During his three-year absence from the army, he smuggled goods in Italy. As a result, he had first-hand knowledge of its geography. Returning to the army in 1792, he rose rapidly through the ranks and in three years’ time had become a general and division commander.

Massena, who was a superb tactician, proved to be one of the best of Bonaparte’s generals. “In his character, he was a man made for authority and command,” wrote Paul Thiebault, an adjutant at the time who eventually became a general. “No one therefore was more in his place than was Massena at the head of his troops.”

Invading Piedmont

As Napoleon prepared to advance into the Piedmont region of Northern Italy, he was confronted by an army of the Kingdom of Sardinia as well as an Austrian army. Blocking the French line of advance at the outset of the campaign, the 17,000-strong Sardinian Army was defending its own lands, but Napoleon believed he could brush it aside because of its low morale.

The Sardinian Army was allied with the larger and more powerful Austrian army. General of Artillery Johann Beaulieu, commanding the Austrians in northern Italy, had 32,000 troops with which to oppose the French advance.

Napoleon swept into the Piedmont on April 12. Two weeks later, Bonaparte and Victor Amadeus III of Sardinia signed the Armistice of Cherasco, which effectively withdrew Sardinia from the War of the First Coalition, leaving just Britain and Austria to face France. With very little effort, Bonaparte had removed the threat of having to confront a Piedmontese-Sardinian army in battle.

With Austria now on her own, Napoleon concentrated his army against Beaulieu. He led his army eastward along the south bank of the Po River in an effort to outflank the Austrian army on the north bank.

The French slipped across the Po at Piacenza on May 6. Four days later near Lodi, Bonaparte caught up with a 10,000-strong Austrian rearguard. Led by General-Major Karl Philipp Sebottendorf, the Austrians had established a seemingly strong position on the far side of the Adda River. Three battalions of Austrian infantry backed by a dozen guns were positioned to cover the wooden bridge and the causeway leading up to it. Oddly, the Austrians had not demolished the bridge.

Bonaparte arrived ahead of Massena’s column and personally sited 24 guns to engage the enemy. He also dispatched Chef de Brigade (equivalent to Colonel) Michel Ordener at the head of several detachments of cavalry to find a ford in order to outflank the Austrians. When Massena arrived to strengthen the French vanguard, Bonaparte ordered a column of grenadiers to storm the bridge. The grenadiers faltered midway under a withering fire from the Austrians.

For a second assault, senior officers Massena, Jean-Baptiste Cervoni, Louis-Alexandre Berthier, and Claude Dallemagne took up places at the head of the column. The senior officers and reinforced grenadiers surged forward again. Some of the attacking troops leaped from the bridge into the shallows and initiated a sharp enfilading fire against the Austrian infantry. The Austrians made a powerful counterattack, but the French assault column eventually punched through the Austrian line. When Sebottendorf observed the French cavalry approaching on his flank, he broke off the action and withdrew.

The Austrians lost 153 killed, 1,700 prisoners, and 16 guns. The cost to the French was 350 casualties. Beaulieu successfully evaded the French pursuit, largely as a result of the Austrian rearguard action.

Bonaparte’s men began calling him “Le Petit Corporal” after his victory at Lodi for the confidence, courage, and determination he had displayed in prying the Austrians from their position.

Liberating Milan

Bonaparte entered Milan on May 15 as a liberator. He extracted funds from the Milanese to pay his troops, some of whom had not received pay in three years. He forced his way across the Mincio River on May 30. In the process, he interposed his forces between the widely separated Austrian formations. The Austrians had little choice but to retreat to the Tyrol. This left Bonaparte free to attack Mantua, the key to the Austrian position in northern Italy.

Situated in the Po Valley, Mantua served as an important road hub, with roads branching out to Padua to the east, Piacenza to the west, Verona and Vicenza to the north, and Modena and Bologna to the south. Italian engineers had created artificial lakes in the 12th century as part of a defensive system. The lakes, fed by the Mincio River, shielded Mantua from attack from the north and east. In his precipitous retreat, Beaulieu had left a garrison of 12,000 men to hold Mantua.

The French attempted to capture Mantua by storm on May 31 but failed. A force of grenadiers captured the San Giorgio suburb three days later. With the suburb as a foothold, the French began to besiege Mantua. The Austrians devoted considerable effort to relieving the siege over the course of the remainder of the campaign. Altogether, they would make four attempts to relieve the garrison.

With Beaulieu outmatched by Bonaparte, the Austrians sent Field Marshal Dagobert von Wurmser to take control of the deteriorating situation. The septuagenarian commander still had sharp wits and therefore was an able opponent.

Bonaparte was unable to conduct a rigorous siege because he lacked the troops to build and maintain a line of circumvallation, which would have kept out a relief force while protecting his long supply line. This allowed Wurmser, who commanded a reinforced field army numbering 55,000, to focus on trying to isolate and destroy enemy detachments guarding the French siege forces. It was in large part a game of wits, and Wurmser initially played it quite well. Napoleon quit the siege on August 1, leaving behind 140 spiked guns that he could ill afford to lose. This allowed Wurmser to resupply the garrison.

The withdrawal was a blessing in disguise for Bonaparte, because it enabled him to fight a war of maneuver against the Austrian columns arrayed against him. On August 4 he smashed a corps led by Lt. Gen. Peter Quasdanovich northwest of Mantua at Lonato. Quasdanovich lost one-third of his 15,000 men in the drubbing.

The following day, Bonaparte engaged the Austrian main army and drove it beyond the Mincio. Wurmser withdrew into the Tyrol, which left the Mantua garrison to fend for itself. Napoleon promptly resumed the siege, albeit without siege guns.

Wurmser moved southwest through the Veneto Province towards Mantua in a second attempt to relieve the siege in early September. Although overtaken and defeated by Bonaparte’s larger army at Bassano on September 8, he nevertheless continued his marchto relieve Mantua. He punched through the French siege lines on September 12 and arrived in the city with 10,000 troops, thus raising the number of Austrian troops in Mantua to 23,000. It was a pyrrhic victory considering that the soldiers and residents of Mantua were already starving. All Wurmser succeeded in doing was exacerbating the already desperate supply situation.

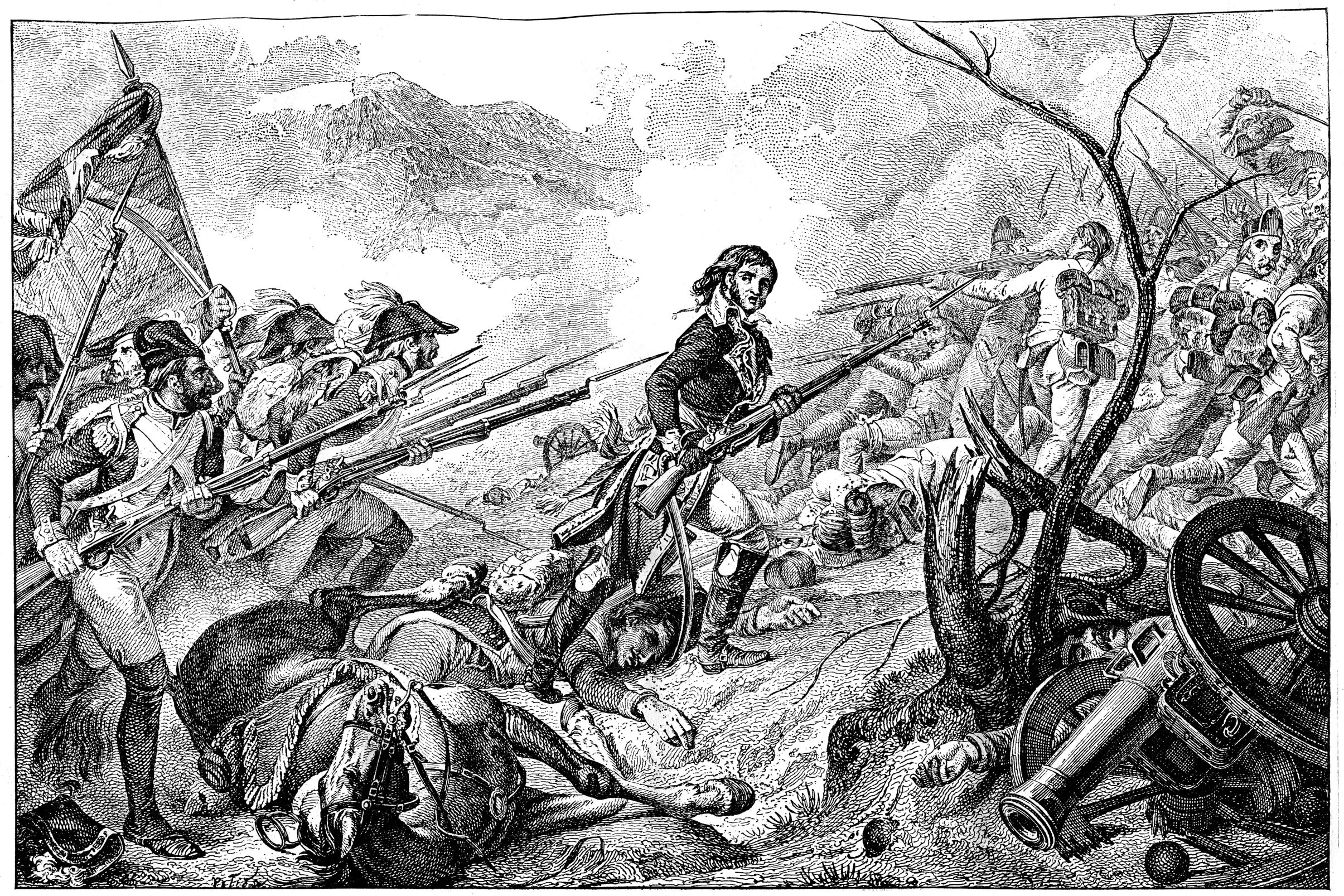

The Austrians dispatched a new army in early November under General of Artillery Joszef Alvinczy to fight its way to Mantua. Bonaparte advanced to intercept Alvinczy’s columns. On November 15, near the village of Arcole, the French vanguard began crossing the Alphone River on a narrow causeway but fell back when confronted with a withering fire from the Austrians. In an attempt to inspire his troops, Napoleon grabbed a flag and waved it about on the causeway, adding to his reputation as a commander who led from the front.

Alvinczy had the advantage in numbers: the Austrians fielded 24,000 troops to Bonaparte’s 20,000. Bonaparte needed to achieve a victory so that he might turn his attention to another Austrian column, numbering 18,000 troops, that was facing a French holding force of 10,000 men. Bonaparte also believed that for the sake of his army’s morale it was important to keep fighting. He sent his men charging against the Austrian position for three days, but the French never succeeded in breaking through. When Massena’s division arrived on November 17, however, Alvinczy feared he might be outflanked, and he withdrew to Vicenza.

A lull in the fighting in December afforded Bonaparte time to meet with the Grand Duke of Tuscany to plan an expedition against the Pope. Bonaparte undertook this mission because the Pope was an implacable enemy of the Revolution. The expedition was superseded, though, by the Austrians’ final attempt to relieve Mantua in January 1797.

The Leadup to the Battle of Rivoli

By that time, the reinforced French army numbered 46,700 men. Bonaparte had arrayed his units across the region. Serurier commanded 10,000 Frenchmen besieging Mantua. Newly minted Division General Barthelemy Joubert commanded another 10,000 French troops stationed at Rivoli. Bonaparte had been observing Joubert throughout the campaign, and the promotion he gave Joubert in December 1796 was a great mark of respect.

By comparison, the Austrians fielded 49,000 at the beginning of the year. Alvinczy’s 28,000-strong Tyrol corps swept south from its base in the Tyrol. Planning to capture La Corona and Rivoli, Alvinczy issued detailed orders to his subordinate commanders.

Meanwhile, Lt. Gen. Marchese Giovanni Provera’s 15,000-man Friuli corps marched west from Padua in two columns. Provera led a 9,000-man column that would march through Legnano to Mantua. Maj. Gen. Adam Bajalich led a 6,000-man column that would march from Bassano through Verona to Mantua.

Alvinczy captured La Corona on January 12, but Joubert blocked his advance on Rivoli. Nevertheless, the Austrians engaged Joubert and forced him to evacuate San Marco, which the Austrians then occupied. Although his troops had been roughly handled by the Austrians, Joubert had succeeded in preventing them from seizing Rivoli.

Napoleon, at Bologna, did not learn of the Austrian advance until January 10. He moved to Verona three days later. Upon his arrival, he learned that Massena’s force of 9,000 men had checked Bajalich’s advance, and General of Division Pierre Augereau had soundly defeated Provera at Legnago. Alvinczy’s plans to relieve Mantua were steadily unraveling.

Bonaparte could not fathom the Austrians’ intent. Nevertheless, he began concentrating his scattered divisions: He ordered General of Division Gabriel Rey to move his 4,000 men to Castelnuovo and General of Brigade Claude Victor to move his 2,000 men to Villafranca.

Bonaparte received a dispatch from Joubert, who was at Rivoli, on the night of January 13. The contents of the report convinced him that Rivoli was the Austrian’s main objective. Joubert informed him that a large force of the enemy had assaulted his position, driving him from the plateau onto the plain. Joubert did not know if he could hold his position without reinforcements.

Bonaparte ordered Joubert to hold Rivoli at all costs. He knew that Alvinczy’s corps had arrived from the north via the Adige River valley. Deeming Alvinczy’s corps the most serious threat, he issued instructions to his subordinates to converge on Rivoli.

Bonaparte ordered Massena to leave 2,000 men to hold Verona and take the other 8,000 to Rivoli. He also ordered General Rey to march at once to Rivoli. And he directed General of Brigade Joachim Murat, who commanded 600 horsemen, to strike Alvinczy from the rear.

Bonaparte departed Verona and arrived at Rivoli at 2:00 a.m. on January 14. Joubert’s troops were deployed for battle on the plain awaiting Bonaparte. When the French commander arrived, he took command of the forces in the field.

The Adige River valley is overshadowed by Monte Baldo, which separates the Adige from Lake Garda. The plain where Joubert was deployed is high above the Adige. It is encircled by the Tasso River, which flows into the Adige south of Rivoli. The roads over which the majority of the Austrians converging on Rivoli had to arrive were of poor quality, which precluded their bringing any ordnance other than mountain guns. The broken terrain also precluded large-scale cavalry actions.

A deep canyon ran from La Corona to San Marco. It afforded access to the rear of Joubert’s division. This was the only route by which cavalry and artillery could be brought onto the battlefield.

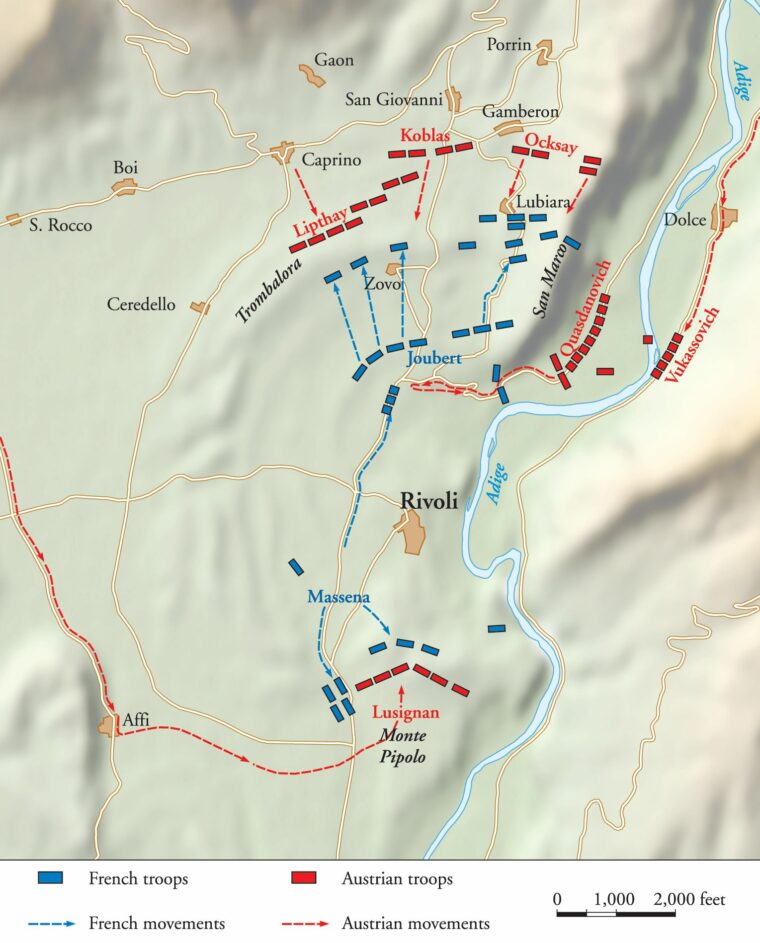

Alvinczy planned to divide his corps into six columns. Colonel Marquis Franz Joseph Lusignan would take 4,500 men on a long circuit around Monte Baldo, far beyond Napoleon’s left flank, and assault the French rear. General-Major Anton Lipthay and General-Major Samuel Koblos, with 3,000 men and 4,100 men, respectively, were to launch a frontal attack against Joubert’s position. General-Major Joseph Ocksay would support them with his 3,500 men.

Alvinczy instructed General-Major Joseph Philipp Vukassovich to march his 2,900 men down the left bank of the Adige River with orders to seize Rivoli from the opposite side of the river. As for Quasdanovich’s 7,000-strong column, it was to pass through the narrow defile connecting La Corona and San Marco.

Ocksay was unable to join Lipthay and Koblos via the road through the Adige Valley; he had to backtrack to Belluno and find a path over Monte Baldo. Lusignan also arrived late after encountering deep snow along his route.

At 4:00 a.m. on January 14, without waiting for Massena’s division, Bonaparte ordered Joubert to retake any ground that had been lost the previous day. This caught Alvinczy completely by surprise, for he had expected the French to remain on the defensive. Bonaparte decided to immediately seize the heights of San Marco because it was the key to the plateau.

The 29th Light Infantry and the 85th Line Infantry formed to the left; the 14th Line Infantry deployed in the center. Adjutant General Honore Vial’s Light Infantry Brigade, which was composed of the 4th, 17th and 22nd Light, supported by the 33rd Line, covered the right.

Massena commanded the left, Berthier led the center, and Joubert directed the right. The 39th Line covered the mouth of the gorge through which Quasdanovich would attempt to reach the battlefield. The 39th, which consisted of just 978 men, deployed in three lines backed by artillery. French skirmishers from the unit took up places on the high walls of the defile from which they could fire on the advancing Austrians.

At 5:00 a.m. General of Brigade Honore Vial’s troops captured the chapel of San Marco from a Croat detachment. He drove the rest of the Austrian outposts back to the villages of San Giovanni and Gamberon. In the center of the battlefield, the 14th Line took Monte Ceredello. On the right, the 85th Line captured the height of Trambasore, and the 29th Light seized the height of Zoro. Bonaparte placed batteries to support each of these forces.

Bonaparte’s line was stretched to the breaking point, but the spirited French soldiers sustained their attack. Indeed, they advanced at faster pace than Bonaparte wished. An Austrian counterattack nearly defeated the 4th Light of Vial’s brigade, but the 17th Light came to their aid just in time. The Austrians, owing to their lack of field artillery, gave way under Joubert’s attack. General Vial, on the French right, pushed the Austrian outpost back beyond Lubiara. The 14th Line, in the French center, cleared the heights of Rovina.

At dawn Alvinczy directed his troops to throw their entire weight against the French infantry. Ocksay moved up his troops on the Austrian left. He commanded some excellent soldiers, a combined grenadier battalion and a battalion of Infantry Regiment Deutschmeister. The Austrian troops collided with the 14th Line and began a ferocious struggle for possession of San Giovanni.

General-Major Koblos also had a combined grenadier battalion, as well as some companies of Mahony Jagers (light infantry). He repeatedly attacked Vial’s brigade, but was unsuccessful in his attempts to defeat it. To assist the hard-pressed soldiers of Vial’s brigade, Joubert rushed the 33rd Line to his aid.

This portion of the battle lasted for two hours, during which the French suffered heavy officer casualties. At the outset of the battle, Joubert had his horse killed from beneath him and spent the rest of the battle afoot. The French left eventually gave way, exposing it to possible encirclement. This allowed the Austrians to send additional forces against the French center. Although in danger of being surrounded, the 14th Line refused its left flank, thwarting the Austrian assault.

Massena arrived at 10:00 a.m. with the 18th, 75th, and 32nd demi-brigades. Bonaparte initially placed him in reserve, but soon ordered him to send the 32nd to reinforce the French left. Bonaparte ordered the 18th to Garda and retained the 75th as a reserve unit.

The 18th demi-brigade soon received new orders to advance to the left of the line of attack, extending their flanks but not getting too spread out. The arrival of the 32nd on the French left stabilized the section, but the Austrians slowly pushed the French back. Lipthay moved through a ravine in an attempt to outflank the 85th Line on the French left, but the 85th had already abandoned its position. The 85th retreated so quickly that the Austrians found themselves behind the 29th. After a spirited resistance, they were driven back in disorder to Rivoli.

When the French right was forced back from Lubiara, Massena tried to rally the French troops, even striking some of them with the flat of his sword. He could not stop the retreat and soon found himself alone with adjutant Paul Thiebault and an aide-de-camp. Thiebault said it was time to be going, but Massena stayed there, whistling while he watched the Austrian skirmishers. Finally, he took off at a gallop and placed himself at the head of the 32nd, which was marching forward with a forbidding resolve.

Massena ordered the 75th to get behind the enemy skirmishers. By late morning the French had restored their right and regained control of Trombasore. Massena led his division forward to plug a breach in the French line, but at the same time the Austrians hit the 14th Line in front and flank. Putting up a gallant resistance, the 14th held its position for a long time. The soldiers of its lead battalion, deployed in San Giovanni, engaged in house-to-house fighting before being driven out. They had succeeded in slowing the pace of the Austrian advance.

The Austrians next attacked the 85th Line and forced it back. They also assaulted Vial’s brigade, driving it back by outflanking it through a wood. The troops fell back to the chapel of San Marco. Joubert, seeing the disorder, made his way to the position of the 14th and ordered them to hold the chapel.

Owing to the heroic resistance of the 14th in the San Marco chapel, Joubert was able to reach the Monte Ceredello plateau. The 14th counterattacked Ocskay’s brigade; in the process, the French soldiers recovered the battery of artillery that had been captured by the Austrians. The battle consisted of “10 hours of alternate charges and routs on both sides,” recalled Joubert.

The two forces, French and Austrian, were roughly equal in numbers, but the Austrians had no artillery except their few mountain guns. Still, the Austrians proved themselves a worthy foe, especially considering that their supply trains had not kept up with Alvinczy’s column and the troops had not eaten in 24 hours.

The French right stood between San Marco and Rovina, the center between Rovina and Zoro, and the left between Zoro and Brenzon. Quasdanovich’s column was marching determinedly through the defile. It would not be long before they ran headlong into the 39th.

Ocskay shelled the 39th with two cannon he had captured. At the same time, Koblos captured entrenchments the 39th had abandoned and advanced as toward Trombasore, where Massena’s men were holding out.

Vukassovich, on the left bank of the Adige River, progressed to a position across from the 39th demi-brigade at Pontare. His troops shelled the 39th, which fell back under the bombardment.

Quasdanovich prepared to charge down the defile, but he faced a major problem: the battle would have to be nearly won before he could get into position. The defile was narrow, and a small force of French could easily block his advance. Although they took substantial casualties, the stout-hearted soldiers of the 39th held the pass. Quasdanovich even tried to reach Monte San Marco by directing part of his column to scale the canyon walls, but they were easily repulsed by fire from the French soldiers.

Shortly before noon, Quasdanovich noted that the ridge overlooking the defile was not occupied in strength by French troops. He ordered his advance guard, comprising a battalion of infantry and six squadrons of cavalry, to push forward and clear the way for his troops to file through. The combination of Quasdanovich’s attack and the fire from Vukassovich’s artillery batteries drove the 39th out of the defile and onto the plain.

For the Austrians, it was an opportune moment to link up. The head of Quasdanovich’s column, consisting of a squadron of staff dragoons and a battalion of Infantry Regiment Callenberger, made it to the plateau under a substantial fire. Three more cavalry squadrons moved up behind the dragoon squadron.

“It only needed an advance of a few hundred paces, only the perseverance of half an hour, and the French army would be defeated,” wrote Austrian officer Johann Baptiste Schels. Joubert concurred in his memoirs. “The situation was desperate.”

The Austrian forces of Lipthay, Koblos, and Ocksay drove Joubert’s men from the heights of San Marco, but the broken ground scattered the Austrian troops. Two small squadrons of French cavalry, about 200 troopers, hit the Austrians’ leading battalion, breaking it up. Their flight sparked panic throughout the rest of the Austrian infantry. The troops of both Koblos and Ocksay shamefully fled from the field.

As a result, Lipthay found his troops uncovered. This gave him little choice but to retreat. The troops had become convinced they were being attacked by a large force of cavalry, and it became impossible to rally them. Alvinczy “was soon left alone and being nearly surrounded was obliged to save himself,” wrote Colonel Thomas Gray, an official observer with the Austrian army.

Joubert was then free to turn much of his force upon Quasdanovich. The French forces deployed in that sector, which included the 39th, elements of Joubert’s division, and 600 horse from General Charles Leclerc’s Brigade, proved more than enough to hold back the Austrians fighting their way up out of the defile. The French infantry and cavalry were supported by a dozen cannon.

The French gunners swept the Austrian infantry battalion and cavalry squadron spearheading the assault with canister. Afterwards, the 39th charged into their flank with fixed bayonets. The force of the assault drove the Austrians back into the defile and prevented the units behind them from advancing.

French light infantry on the southern slope of Monte San Marco poured a withering fire into the Austrian cavalry in the defile. The entire column became disordered, which intensified when a shell landed in an ammunition caisson, and its explosion killed many men. The Austrians slowly withdrew from the defile.

Lusignan, unaware of it, was now isolated. He reached his destination at Monte Pipolo after noon and discharged two volleys of musketry to alert Alvinczy of his arrival. Unfortunately, there was nothing Alvinczy could do; Lusignan was too late to influence the battle.

“They are ours,” Bonaparte said with obvious delight. He detached the 18th, a battalion of the 75th, and some cavalry to confront them. The troops were supported by several 12-pounder cannon. General Rey arrived from Castelnuovo just in time to strike the rear of General Lusignan’s Brigade. Outnumbered, surrounded, and unable to break free, Lusignan lost nearly his entire brigade before reaching Garda. Lusignan’s men had reached the limit of their endurance and many dropped out of the column. The French pursuers took most of the stragglers prisoner. Lusignan, though, escaped in a boat across Lake Garda.

Quasdanovich, after his defeat at the gorge, withdrew back up the defile to Rivalta. Alvinczy rallied his three units at the foot of Monte Baldo. He believed that if he did not maintain contact, Bonaparte would be free to join the forces besieging Mantua and assault Provera.

Yet he also realized that if the French attacked him in the broken country, they could surround him and take his entire command. To help prevent this, he ordered Quasdanovich to send him two battalions of infantry and two cavalry squadrons. Not knowing what had happened to Lusignan, Alvinczy did not want to depart before ascertaining whether there was any way he might support him.

Bonaparte wanted to assault Alvinczi’s center that afternoon but received word that Provera had eluded Augereau and was marching toward Mantua. Deciding that Mantua presented the greater danger, he ordered Massena to withdraw his division and strike out for it at daybreak. He left Rey to support Joubert and immediately left for Mantua himself. At 5:00 a.m. Bonaparte sent a letter to Joubert making it clear that he did not consider the work at Rivoli finished. He ordered Joubert to move forward early on January 15 and occupy La Corona. Bonaparte told Joubert that he had full confidence in his ability to defeat the Austrians, and therefore he did not plan to return to Rivoli.

Joubert ordered the 4th Light to attack San Marco two hours before dawn on January 15. By daybreak, they were already forcing the Austrians back. Joubert placed General Rey’s division in the French center. He sent Vial across Monte Magnone to break Alvinczy’s left flank, and sent Chef de Brigade Antoine Joseph Veaux with a strong force across Monte Baldo to outflank the Austrian right. Murat arrived at Lake Garda with 600 cavalry and assisted Veaux in turning Alvinczy’s right.

Almost as soon as Joubert’s attack began, Alvinczy knew he was defeated. His troops were simply too exhausted to resist the French. For that reason, he ordered a general retreat.

By that point, it was too late to save his army. If the retreat had been ordered the previous night, under cover of darkness, it might have succeeded; however, in front of a victorious enemy, it was nearly impossible. Alvinczy himself managed to escape before the main French attack struck. When the French assaulted the Austrians at full strength, they routed them. In the two days, the Austrians had suffered 3,000 killed and wounded and 11,000 captured. As for the French, they lost 4,000 killed and wounded.

The victory had both near-term and far-reaching benefits for Bonaparte and his Army of Italy. First, the triumph of Rivoli compelled the surrender of Mantua. Second, the Austrians abandoned northern Italy. Third, it forced the Austrians to accept the unfavorable Peace of Campio Formio. Fourth, it propelled Bonaparte to new heights in the eyes of the French people.

At the same time that the French under Joubert were destroying the Austrian army under Alvinczy, Provero arrived at Mantua. His 5,000 men were badly outnumbered by those of the five divisions that Bonaparte concentrated around Mantua. On January 16 Provera attempted to link with Wurmser by capturing La Favorita and opening a way into the citadel. Outnumbered seven to one, after a vicious fight, Provera surrendered his whole division. “So here we are in the same positions as before!” Bonaparte wrote to Joubert. “Alvinczy cannot say the same.”

Bonaparte, who was at that point free of the Austrian threat, marched south into the Papal territory. He forced Pope Pius VI to pay a large part of France’s cost for the war. Wurmser held out in Mantua for only two more weeks after the disasters at Rivoli and La Favorita. He surrendered Mantua on February 2. Of the 30,000-man garrison, 18,000 men had died from starvation and disease.

Bonaparte received reinforcements and subsequently carried the war toward Austria. Emperor Francis II placed Archduke Charles in command of the Austrian troops, but the archduke did not have nearly enough men to confront Napoleon. For that reason, Charles fell slowly back, losing men all the way. Bonaparte pursued him doggedly through the Alps. On April 6 he arrived at Leoben, just 95 miles from Vienna. Austria accepted a truce. The empire and the First French Republic signed the Peace of Leoben on April 18. This ended the War of the First Coalition; however, Great Britain and France remained at war with each other. As for Bonaparte, he had won a stunning victory in a difficult campaign against the Austrians that stood as a major milestone in his illustrious career.