By Vincent B. Hawkins

Frederick the Great put to use what he learned from his successes and failures. At age 28, new king Frederick Wilhelm II (the Great) burst out of Prussia in an attack on Silesia, which lay within the domain of Maria Theresa, Queen of Austria and Empress of the Holy Roman Empire. It was 1740, and the new king had begun to learn the vicissitudes of war. Over the next five years until the end of the First and Second Silesian Wars, Frederick had his share of both victories and defeats. By 1745, a queasy peace was arranged. But Maria Theresa was furious at the loss of Silesia and she wanted it back.

The Silesian Wars, also embraced under the name Wars of Austrian Succession, were a struggle between the upstart but adroit state of Prussia and the older, larger empire of Austria for dominance over central Europe. The struggle was not yet over; both Prussia and Austria kept prepared for war after the truce of 1745, knowing the fighting would eventually resume.

In the meantime, Frederick nurtured his army. Although relatively small compared to the size of its foe’s, the Prussian army was fast earning a reputation for its superior training, discipline, and military skill. These factors, combined with its almost sacred devotion to Frederick, made the Prussian army into a force to be reckoned with. No less important were the developing military skills of the king himself. Having suffered several reverses in his first campaigns with ranks inherited from his father, Frederick initiated a total restructuring of the army. He took complete control, imposing his newly designed concepts of warfare and tactics on every department and personally overseeing every aspect of the army’s existence.

This style of leadership was drastically different from that employed by other European leaders of the time, and in conjunction with the improved ability of the newly reformed army, had repeatedly proved itself on several battlefields. It was fast becoming apparent to the leaders of Europe that something had to be done, and quickly, about upstart Prussia.

Defeat and Humiliation Fueled Theresa

The person most vexed by Prussia’s increasing power and seemingly unending military success was, of course, Maria Theresa. Over the course of the Silesian Wars she had seen her territories invaded, her armies defeated, her great generals humbled, and her sovereignty threatened.

The defeat and humiliation she and her people had suffered at the hands of Frederick had left a bitter rancor within her. She therefore resolved to avenge Austria’s loss and at the same time destroy Prussia. The first step was to revitalize her defeated and demoralized army. Recognizing “that her salvation and that of her house depended, after God, on the army,” she determined “to care for the army more as a mother than as a sovereign.” Consequently, from 1748 to 1756 the Austrian army underwent a major transformation. New regulations for all branches of the service were issued. Uniforms, equipment, and weapons were updated and systematized. The infantry drill was refined and formation maneuvers practiced to near perfection. The artillery, long a source of problems, received special attention and rapidly improved in both size and ability. The cavalry was improved in both structure and quality. A military academy was established at Wiener Neustadt in 1752 to provide the officer corps with a uniform system of training and to create a sense of professionalism in their service. The various departments of the army were, for the most part, restructured to enhance performance. In effect, the entire Austrian army underwent a kind of “Prussianization,” essentially copying the military methods and manner of its enemy.

The tense peace that followed the Second Silesian War disintegrated in 1756. Threatened with an alliance among France, Russia, and Austria, Frederick struck first, invading Saxony to his south in August, thus igniting the Seven Years’ War. His initial steps were successes, defeating an Austrian army at Lobositz in October on the road from Dresden, capital of Saxony, to Prague, capital of Bohemia, which was south of Saxony and west of Silesia. In May 1757, Frederick laid siege to Prague, then turned to face Austrian Marshal Leopold von Daun at Kolin. Daun, an astute commander and worthy opponent of the deft Frederick, defeated him on June 16. Frederick abandoned the siege at Prague and retreated into Saxony.

Frederick retreated again, to counter a threat against Berlin, then countermarched to Rossbach near Leipzig in Saxony. Here, in November, his army of 21,000 overcame 41,000 soldiers of France and a coalition of German states.

With the threat of the French and German armies out of the way, Frederick turned his attention back to the Austrians, moving his main force to Leipzig. Leaving one detachment under General Keith to watch the Austrian forces in Bohemia, and another under his brother Prince Henry in Saxony, Frederick left Leipzig on November 13 at the head of 12,000 men and marched for Silesia. The king’s express objective was simple in design though it would probably prove difficult to execute: to retrieve his waning military fortunes in Silesia.

Austria’s Army Reached Breslau with 84,000 Men

The very day Frederick left Leipzig, an Austrian force captured the new Prussian fortress at Schweidnitz, thus securing the communications of the main Austrian army under Maria Theresa’s brother-in-law, Prince Charles of Lorraine, with its base in Bohemia. The Austrians continued advancing into Silesia, closing in on the capital at Breslau, where the Duke of Bevern and the last Prussian army in Silesia stood to meet them.

On November 22 the main Austrian army, some 84,000 strong, reached Breslau and attacked. Bevern’s 28,000 men bravely held their ground for several hours against the Austrian assault. But by 2 pm their overextended flanks crumbled and the army retreated to Breslau. Bevern then gave orders to withdraw to Glogau, but he was captured making a reconnaissance before the retreat could commence. The Prussian army, disordered and leaderless, marched away as best it could, abandoning the capital and its garrison, which surrendered on November 25. Prussian losses were 6,350 men and 29 guns to the Austrians’ 5,581 men. Two days later Frederick received the news that he had lost his last accessible base in central Silesia.

On November 28 Frederick reached Parchwitz where he assembled his scattered army and began the preparations for retaking Silesia. He was joined there on December 2 by General H.J. von Zieten, who had gathered up the remnants of Bevern’s beaten force and brought them safely back to join with Frederick, thus giving the king a total of about 35,000 men. Bevern’s soldiers were thoroughly demoralized by their misfortunes and were terrified at the prospect of facing the king after their ignoble defeat at Breslau. To their surprise, Frederick, instead of chastising them for their loss, openly welcomed them and spared no pains to restore their morale.

“This army was discouraged, and demoralized by a recent defeat,” Frederick recalled later. “I appealed to the officers’ sense of honor; I recalled what they had done in the past, and strove to overcome the gloomy impression of what they had just experienced; I actually dispensed wine as a means of doing something to raise those downcast spirits … I talked to the soldiers … the men who had beaten the French at Rossbach persuaded their comrades to draw fresh courage…. A little rest enabled the soldiers to recover, and the army was in the mood to expunge, at the first opportunity, the insult which it had received on the 22nd.”

Frederick’s sole purpose was to make his soldiers useful again for the next battle, but in so doing he drew closer to them than he ever had before or ever would again.

Recorded a contemporary: “During these winter days the king camped in the open air like one of his private soldiers. He used to warm himself at their fires, and then make room for others to take his place. He talked with the soldiers as if they were of his own kind. He sympathized with the travails they had undergone, and, in the most friendly possible way, he encouraged them to behave like heroes just once more.”

“The Old Warriors Shook Each Other by the Hand and Promised to Stand by One Another Loyally”

Having effectively restored the morale of his troops, Frederick then spoke to his generals. In a speech he delivered on the morning of December 3, Frederick conveyed to them the urgency of their situation and the importance of what was at stake, exhorting them to do their utmost in the name of king and country. Greatly moved by this address, “The old warriors, who had already won so many battles under Frederick, shook each other by the hand and promised to stand by one another loyally,” wrote a subaltern in the Seven Years’ War. “They made the young troops swear not to shrink before the enemy, but to go straight at them regardless of the opposition.”

Frederick’s army might not have been as large as it once was, but, as put by modern biographer Christopher Duffy, “never again was his army more truly national in character, for the Saxons and many of the foreign troops had been shed in the battles and forced marches of the last three months, leaving Frederick with a small but excellent force of 35,000 men, mostly native Brandenburgers, Pomeranians, and Magdeburgers.” Their morale was high, their officers determined. They were as ready as any army could be for the upcoming battle.

Early on December 4 the army began moving east in four columns screened by an advance guard. Upon reaching the village of Neumarkt, the advance guard was surprised to find the enemy’s field bakery, a sign that their main body could not be far away. Two regiments of Austrian hussars were subsequently driven off, and 500 Croats, along with the bakery and its large bread stores, were captured. Frederick made his headquarters in Neumarkt, and later that evening was informed that the Austrian army had crossed over the Lohe and Schweidnitzer-Wasser and was camped on the near side. Frederick decided to attack early the next morning before the enemy could firmly establish a defensive position.

The risks of such a plan were far greater than Frederick knew. He had estimated the Austrian army at only about 39,000 men. In fact, Prince Charles had an army of 85 battalions, 125 squadrons, and 235 guns, totaling some 65,000 men. To meet this huge force, Frederick had only 381/2 battalions; 133 squadrons; 78 heavy guns, of which 10 were 12-pounder fortress guns from Glogau, nicknamed “Brummers” (Bellowers); and 98 battalion guns, totaling only 35,000 men.

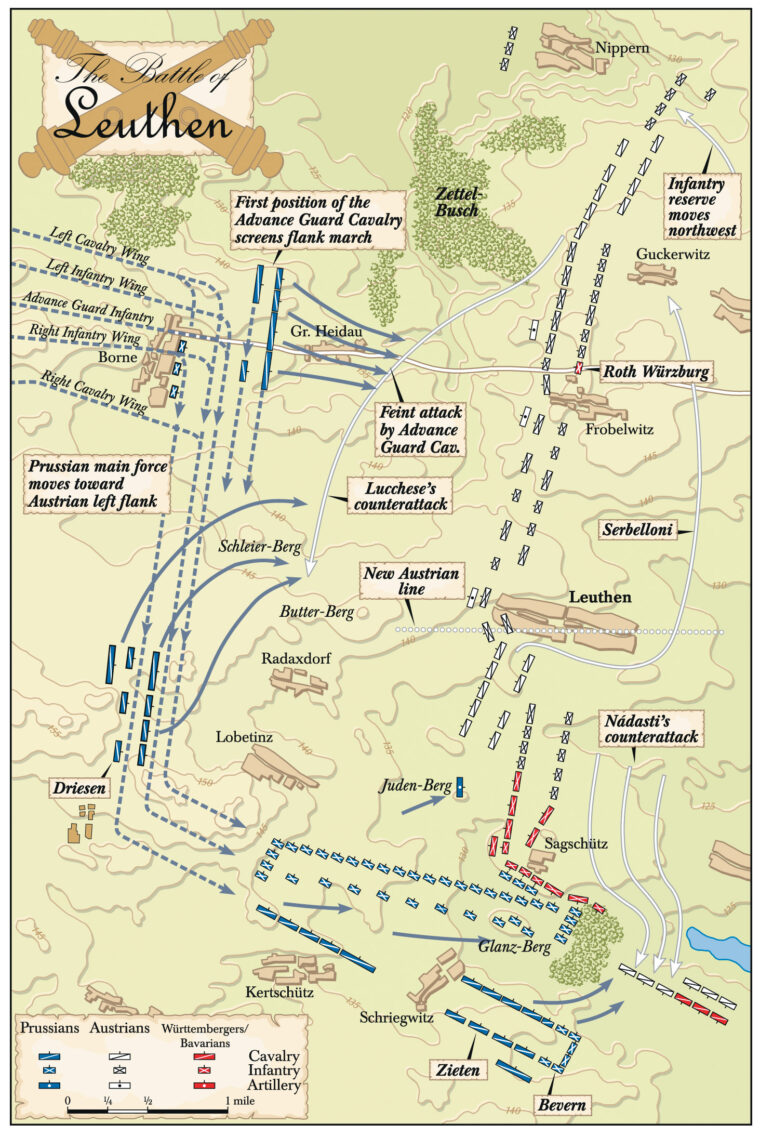

Furthermore, the Austrians had taken up a strong position along a long ridge, their front stretching some four miles. Starting on the Austrian right flank to the north, their line passed behind the village of Nippern, then the Zettel-Busch (the only wooded country in the area), through the villages of Frobelwitz and Leuthen to Sagschütz, on their left flank. Several prominent knolls also dotted the landscape in front of their position, including the Butter-Berg, opposite Leuthen, and the Juden-Berg, northwest of Sagschütz.

Frederick Woke His Army at 4 AM and Set Off For Battle

The king rose early on December 5, and before daybreak rode from the right wing of the army to his Garde du Corps: “The weather was fine but very cold,” recounted an early biographer of Frederick. “The troopers were standing by their horses and clapping their hands to keep warm. ‘Good morning, Garde du Corps!’ ‘The same to you, Your Majesty!’ replied an old cavalryman. ‘How goes it?’ inquired the king. ‘Well enough, but it’s bloody cold!’ ‘Have a little patience, lads, today is going to be a little too hot!’”

Frederick roused his army at 4 am, and by 5 or 6 am they began moving toward the village of Borne by columns in four great wings, two central wings of infantry with two more of cavalry, one on either side. Prussian cavalry won a short, sharp fight with some Austrian light cavalry at Borne, and the army pushed on into the ground beyond. A mist hung over the ground, which was lightly covered with snow, and Frederick saw that the army had emerged from Borne opposite the right center of the Austrian position. A quick reconnaissance revealed that the Austrian right was anchored on the Zettel-Busch and that its left fell short of the support of the Schweidnitzer-Wasser. Although the enemy position was strong, Frederick and his generals knew every inch of this ground because it was where they held their autumn maneuvers. Frederick realized that the Schleier-Berg and Sophien-Berg hills afforded him the opportunity to execute a concealed march to the south, which would allow him to maneuver onto the enemy’s exposed left flank.

To convince the enemy that his intentions were to attack their right flank, Frederick deployed the cavalry of the advance guard a thousand paces in front of Borne in full view of the enemy. He supported the cavalry with some infantry from the main body, thus giving the impression that the army was forming to attack. This force then began to feint an attack against the Austrian right. “The Austrians … stood in endless great lines, and they could hardly credit their senses when they saw the little body of Prussians advancing to attack them,” reported a 19th-century historian of the war. An Austrian general, observing the precision of the Prussian advance, named them the “Berlin watch parade.” But the ruse worked—Prince Charles quickly moved nine battalions from the reserve on his left to support the impending threat to his right.

As the Prussian columns began passing through and around Borne, Frederick ordered them to turn right and march south. By some complicated maneuvering carried out under the watchful eye of the king, the four wings of the army were reformed into three lines. Although the ground in this area was some of the flattest in all Silesia, in a short while the Prussian columns disappeared from sight of the enemy. Due to his intimate knowledge of the terrain, Frederick was able to use the hills and hollows to screen his movements. Further, to ensure that no confusion occurred and his hand wasn’t tipped before he was ready, he moved the army well past the enemy’s flank, passing behind Lobotinz before executing a half-left turn to the east-southeast. By midday the Prussian columns were crossing the enemy’s left flank and advancing on Sagschütz.

By positioning himself between the enemy and his own army, Frederick was able to accurately direct the army’s march, maneuvering it to exactly the position he desired. When the lead elements of the army, composed of Zieten’s cavalry and Bevern’s infantry, wheeled into position to the right of Schriegwitz (see map), Frederick halted the march. Carefully, and with much deliberation, he aligned his troops for the attack.

“You Must Go Straight at Them and Turn Them Out With the Bayonet.”

According to Duffy, “The initial breakthrough was to be accomplished by Major General Wedel with the three remaining battalions of the advance guard, namely the regiment of Meyerinck (No. 26) and the second battalion of Itzenplitz (No. 13). To their right rear was a column of four battalions, mostly grenadiers, and a battery of 12-pounders which was moving up to a site on the low Glanz-Berg. The main body of the infantry was arrayed in a staggered line of battalions extending back to the left at fifty-pace intervals. The whole formed a textbook example of the Oblique Order” (see sidebar).

Frederick stopped to speak to Frei-Corporals Barsewisch and Unruh who bore the colors of the Meyerinck Regiment, the lead unit of the advance. “‘Ensigns of the Life Company, take heed!’ he shouted,” according to Barsewisch. “‘You must march against the abatis, but don’t advance so quickly that the army can’t keep up with you.’ Whereupon His Majesty indicated the position of the enemy line to our battalions, and told the men: ‘Lads, do you see the whitecoats over there? You’ve got to throw them out of their earthwork. You must go straight at them and turn them out with the bayonet. I will come up with five [sic] grenadier battalions and the whole army to support you. It’s a case of do or die! You’ve got the enemy in front, and all our army behind. There’s no space to retreat, and the only way to go forward is to beat the enemy.’”

Prince Moritz then rode up to remind the king that it was well past noon and the short winter day afforded only a few more hours of daylight. A little after 1 pm Frederick gave the order and the Prussian line advanced. Concerned that the attack would get out of hand and the army would suffer a repeat performance of Prague or Kolin, Frederick repeatedly sent messengers ordering the lead battalions to adjust their speed.

General Franz Leopold Nádasti, commanding the Austrian left, had seen the Prussian army forming to the south and sent several messages to Prince Charles informing him of the impending danger to that flank. But Charles, still convinced that the main attack was to be delivered against his right, did not respond. Unwittingly, he had given Frederick all the time he needed to prepare and launch his attack. Fate further conspired against the Austrians in that their far left flank was protected by 14 battalions of German auxiliaries, mostly Württembergers and some Bavarians, considered to be the least reliable soldiers in their army. It was these troops that would bear the full force of Frederick’s attack.

Zieten Routed the Austian Army and Nearly Annihilated the Dragoons

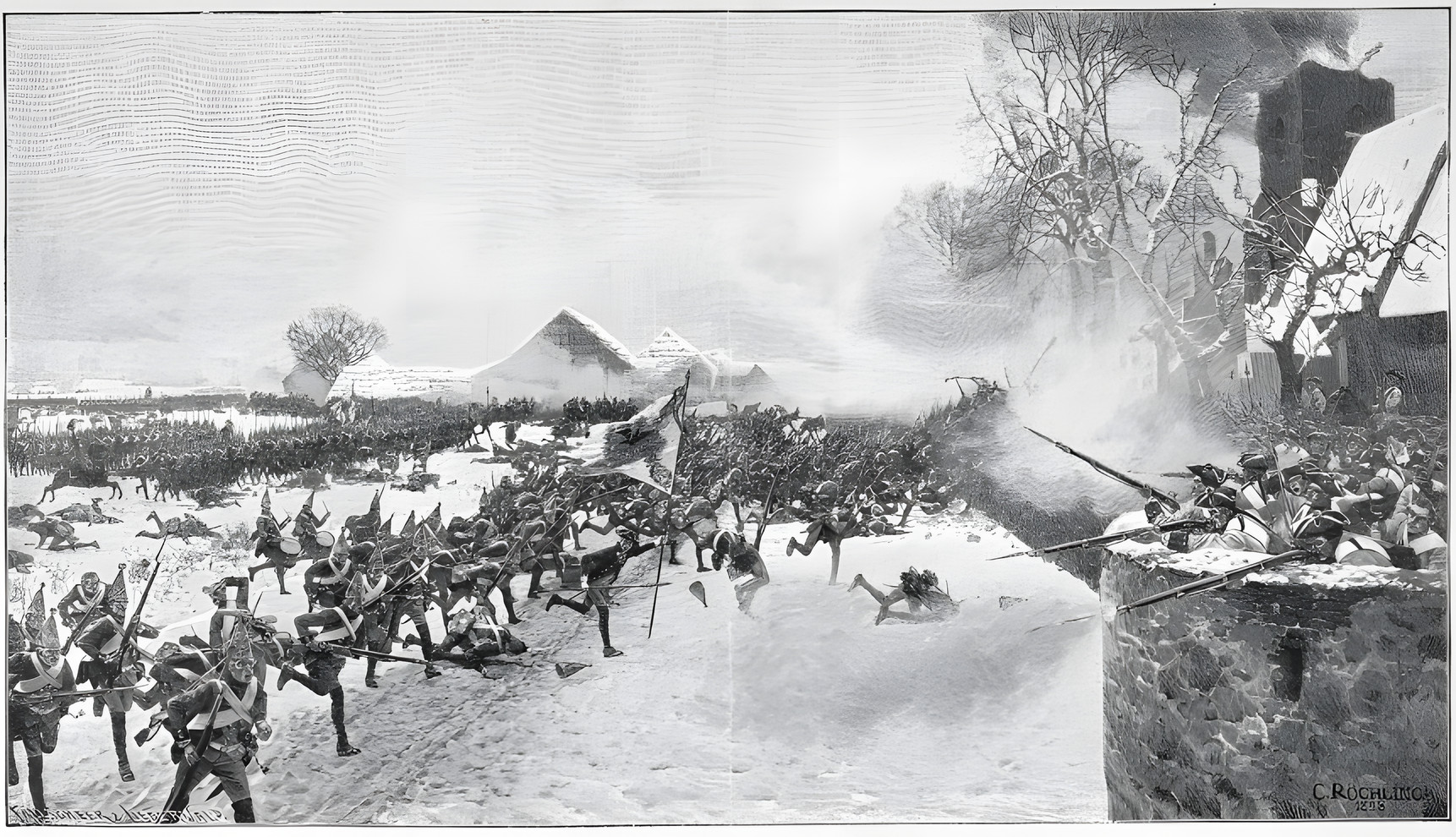

The Prussian advance crashed into the leading Württemberg units, which, after a short but determined resistance, broke and ran back into their own lines. The remaining Württemberg battalions, seeing this flight and the Prussians coming straight at them, fled without firing a shot. The Prussian line carried on toward Leuthen, ably supported by the extraordinary mobility displayed by the heavy batteries that had taken position on the Juden-Berg and were firing into the front and flank of the Austrians around Sagschütz. On the far Austrian left, General Nádasti tried to save his position by throwing his cavalry against the advancing Prussian infantry. Zieten quickly countered with all 53 of his squadrons, and after a fierce contest routed the Austrian cavalry from the field, capturing 15 guns and nearly annihilating a regiment of Austrian dragoons.

Prince Charles, seeing this imposing threat against his flank and finally realizing he had been tricked, tried to restore the position by shifting some battalions from his second line to shore up his left. This proved to be of no use, however, and he was forced to wheel the entire army to face south, presenting a new front that ran through and several hundred paces on either side of Leuthen. This new formation packed the Austrians together into a dense mass, in some areas reaching 30 deep, which in turn provided an excellent target in enfilade for the Prussian guns on the Butter-Berg.

The Prince de Ligne, a captain in an Austrian infantry regiment of the reserves, recalled: “Besides a general cannonade such as can hardly be imagined, there was a rain of case-shot upon this Battalion, of which I, as there was no Colonel left, had to take command; and a third Battalion of the Royal Prussian Foot Guards, which had already made several of our regiments pass that kind of muster, gave, at a distance of eighty paces, the liveliest fire on us. It stood as if on parade-ground, that third Battalion, and waited for us, without stirring.”

At around 3:30 the second phase of the battle began when the Prussians attacked this new Austrian line. Concentrating on Leuthen itself, the Prussians hammered away for over 30 minutes against stiffening resistance. The third battalion of the Garde advanced against the village gates, and, according to a participant, the senior captain (later field marshal), Moellendorff, “sprang forward with the cry ‘I want someone else up here! Lads, follow me!’ They made for the barricaded gates and battered and tore down the door and, with their leader at their head, the little band broke through under the barrels of 10 leveled muskets. Now that the gateway was captured, the battalion pressed through in column and spread out.”

Whole Austrian Battalions Threw Down Weapons and Fled

The Prussians were forced to storm several of the buildings, including the church, before they finally carried the village. The Austrians reformed their line behind the village and prepared to stand their ground. Generals Lucchese and Serbelloni of the Austrian cavalry then attempted to sweep the Prussian line by throwing 70 squadrons against their open left flank. Lieutenant General von Driesen, in command of the cavalry on the Prussian left, saw this move and countered it by committing his 40 squadrons. The first wave of Prussian cavalry did not fare too well, and when the contest began to go against them, a second wave composed of 30 squadrons came to their rescue, overthrowing the Austrian cavalry and driving them down on their own infantry north of Leuthen. This proved to be too much for the Austrians, and whole battalions threw down their weapons and fled, the growing tide of fugitives sweeping away those who tried to make a stand.

As darkness began to fall, Frederick gathered a regiment of cuirassiers and three battalions of grenadiers and set off through the now falling snow to block the bridge at Lissa, five miles behind the battlefield. By this effort he intended to prevent the Austrians from crossing the Schweidnitzer-Wasser and establishing a new line on the opposite bank. By 7 pm his little force had driven the Austrians out of the buildings that covered the bridge, and Frederick retired to the castle of Lissa. Entering the castle, Frederick surprised several Austrian officers in the process of quartering.

“‘Bon soir, Messiurs!’ said he, with a gay tone, stepping in,” according to historian Thomas Carlyle. “‘Is there still room left, think you?’ The Austrians, bowing to the dust, make way reverently to the divinity that hedges a King of this sort; mutely escort him to the best room (such the popular account); and for certain make off, they and theirs, towards the Bridge, which lies a little farther east, at the end of the village.”

When darkness put an end to the battle around Leuthen, the entire Prussian army followed in the king’s tracks to Lissa. Later, according to Duffy, Frederick heard “how the entire army, still marching through the night, had raised its voice in the chorale ‘Nun danket alle Gott!’ (Now all thank God!) The sound breathed fresh life into men who were almost paralyzed with cold and exhaustion, and some of the veterans were to remember it as their most vivid experience of the war.”

The defeated Austrians recoiled toward the mountain borders, leaving some 10,000 dead and wounded and around 12,000 prisoners, totaling one-third of their army, along with 51 colors and 116 guns. Furthermore, by his hurried and confused retreat, Prince Charles left 17,000 men stranded in Breslau, who surrendered on December 20. The Prussians lost some 6,382 men, of whom most were only slightly wounded. That night, at his headquarters in Lissa, Frederick assembled the officers Zieten, Driesen, Retzow, Wedell, Moritz of Dessau, and his younger brother, Ferdinand. Thanking them for their service, Frederick said, “Meine Herren, after such a spell of work, you deserve a rest. This day will transmit the glory of your name and our Nation to all posterity.”

“All His Maneuvers in This Battle Were in Harmony With the Principles of War.”

Frederick had his decisive victory, the campaign was won, and Silesia was saved for Prussia. Frederick’s plan was well thought out and nearly flawless, and his army executed it magnificently, performing with a high degree of morale and skill superior even in a well-disciplined force.

“Almost every commentator has drawn attention to the high morale of the Prussian troops, Frederick’s knowledge and exploitation of the terrain, the unhurried speed of the attack, the mobility and destructive fire of the artillery, the responsiveness of the infantry, the devastating intervention by the cavalry of the left wing, and the initiative shown at every level from Lieutenant-General Driesen to Captain Moellendorff,” wrote Duffy.

Napoleon considered Frederick’s performance at Leuthen “a masterpiece of movements, maneuvers and resolution” which would in itself suffice “to immortalize Frederick and rank him amongst the greatest generals. He attacks an army of superior strength to his own, in position and victorious, with an army composed in part of troops which had lately been defeated, and gains a complete victory without purchasing it by a loss disproportionate to the result. All his maneuvers in this battle were in harmony with the principles of war.”

Following the fall of Breslau, Frederick put the army into winter quarters throughout central Silesia and southern Saxony. The next year would bring a new campaign, and Prussia’s fortunes, while rescued for the moment, were not free of peril. There would be other periods of great danger before the war was finally concluded. But for the moment, the king and his army could relax and take comfort of the part they had played in, according to a near contemporary, “that extraordinary campaign, the most fertile in battles, reverses and great events, of any presented in modern history.”

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments