By Arnold Blumberg

The European wars of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were characterized by large-scale clashes between similarly armed soldiers employing sabers, cannons, and weapons like the iconic Baker rifle. Firepower dominated the battlefields. The foot soldier of the period plied his bloody trade using sturdy, easy-to-operate muskets—flintlock, smoothbore muzzle-loaders, but barely accurate at a distance of 100 yards. To improve the ratio of hits, blocks of closely packed musketeers would point their weapons at opposing densely packed ranks of enemy troops and fire as rapidly as they could. The object was to deliver such a sustained and overwhelming volume of lead into the enemy’s close formations that unit cohesion and morale would be lost, causing the foe to flee the field before the two sides came into close contact with bayonets.

From the mid-17th through the late 18th centuries, infantry weapons and tactics changed very little. With the advent of the French Revolution, however, the stimulus for change arose in the form of large-scale use of skirmisher tactics on the battlefield. French musketeers forming “clouds” or “swarms” of open-order troops firing from minimal distance at their targets presented a mortal threat to the exposed lines and columns of the enemies of the young Republic. By 1800 all the major military powers on the European continent were attempting to emulate French tactics. Most fielded musket-armed men to counter the French threat. The Prussians created a small number of rifle-carrying companies called Schutzen to deal with the problem; the British addressed the issue by forming special rifle units of battalion size.

Rifles had made their first limited appearance on European battlefields in the early 17th century. In the 1620s, King Christian IV of Denmark outfitted his personal bodyguards with rifles. Norwegian ski troops used them in the early part of the next century, while the 1670s saw French cavalry scouts employ them on campaign. In 1740, Frederick the Great’s Prussian army established a temporary rifle corps; four years later it became permanent. The British used rifles, or rifle carbines, for the first time when 50 of the weapons accompanied a military force assigned to relieve Louisbourg in North America.

Rifles were seen largely as a German hunting weapon, not as a tool of war, and they were slow to emerge as a military weapon. Nevertheless, the British Army expanded its use of rifles during the French and Indian War, when it equipped selected light troops and marksmen in the 27th, 42nd, 44th, 46th, 55th and 60th regiments of foot with flintlock, muzzle-loading rifles of German manufacture. During the same period, the British depended on German auxiliaries to supply the limited number of rifle-armed light troops used in the Crown’s contingents fighting in Europe.

Over the next 40 years, the English government made tentative steps toward developing a domestic version of the rifle. Although it looked at such designs as the Pattern 1776 Infantry Rifle and the breech-loader Ferguson model, the country continued to purchase foreign-made rifles in such volume that thousands were in storage or in use by active-duty forces from the Caribbean to the Mediterranean. It was not until the start of the next century, however, that a shift in attitude reversed the Crown’s longstanding practice of buying foreign-made rifles.

The surge in rifle interest in Great Britain began in 1799 with the creation of the Experimental Corps of Riflemen. This formation came about as a counter to French skirmisher tactics. The availability of rifles in British arsenals and their increasing use boosted support for the new riflemen; but the clincher was the new-found “rifle consciousness” within the Board of Ordnance, the governmental organ that approved all designs, manufacture, purchases and maintenance of British military armament.

By the end of the 18th century, the board had reversed itself on the utility of the rifle. For decades, the British had rejected the use of rifles in large numbers, basing its opposition on a number of suppositions: that the rifle was a civilian hunting weapon and no doctrine for its use had ever been developed for the battlefield; that it took at least three times as long to load as a smoothbore musket; that the requirement for highly trained riflemen could never be met; that the need to thoroughly clean a rifle after every 20 shots further reduced firepower; and that rifles cost more than smoothbores.

The start of the new century found the board convinced that the rifle’s longer effective range (about 150 yards for the rifle, less than 100 yards for the smoothbore musket) and its improved accuracy far outweighed the old objections. Furthermore, hard and extensive training of British regulars overcame the fear that they could not be turned into expert marksmen. To complete the equation, however, a British-made design for rifles had to be obtained.

There Was No Official Record of the Rifle Design Tests and Trials

In late 1799, the board invited various leading gun makers to submit their designs for trials to be held the next year at Woolwich, the Army’s proving grounds. One of the designers was Ezekiel Baker, a master gunsmith from Whitechapel. Baker delivered seven different types of rifle barrels fitted with a number of fitted sights. These formed the basis for a series of trials before a committee of field officers in January and February 1800. The trials at Woolwich consisted of eight barrels being fired at 300 yards, 12 rounds each, from a fixed mortar bed and from the shoulder.

There was no official record of the tests—the only account of the trials appeared two years later in Baker’s book, Remarks on Rifle Guns. Baker recounted that his opposition numbered some of the finest gunmakers in England—Durs Egg, Samuel Galton, Henry Nock, and a Mr. German. According to Baker “there were barrels of French, German, Spanish, Dutch, American, and all nations brought forward in competition: but mine beat them all, in a trial at Woolwich before the Committee—the distance three hundred yards. My barrel was two feet six inches, with a twenty to the pound bore ball, rifles one quarter turn in the angle of the barrel.” Baker’s immodest story of how he won the rifle contract left out one crucial fact: that he was a close friend of the Prince of Wales, heir to the British throne.

In March 1800, the board awarded Baker an order for a number of pattern rifles and barrels so that they could assess various designs and calibers. Baker’s first two models were immediately rejected on the advice of Colonel Coote Manningham, the first commander of the nascent Rifle Corps, for whose troops a rifle design had been sought. Baker’s original presentation had been along the dimensions of the standard infantry musket. Manningham’s objection was based on the weight of the piece—it was too heavy. He was concerned that the rifle’s weight would impede his men’s rapid movement in the field. The colonel instructed Baker to base his rifle on a German Jaeger (hunter) rifle design using a 30-inch barrel, a .625-caliber round, and seven square grooves making one complete turn every 19 feet.

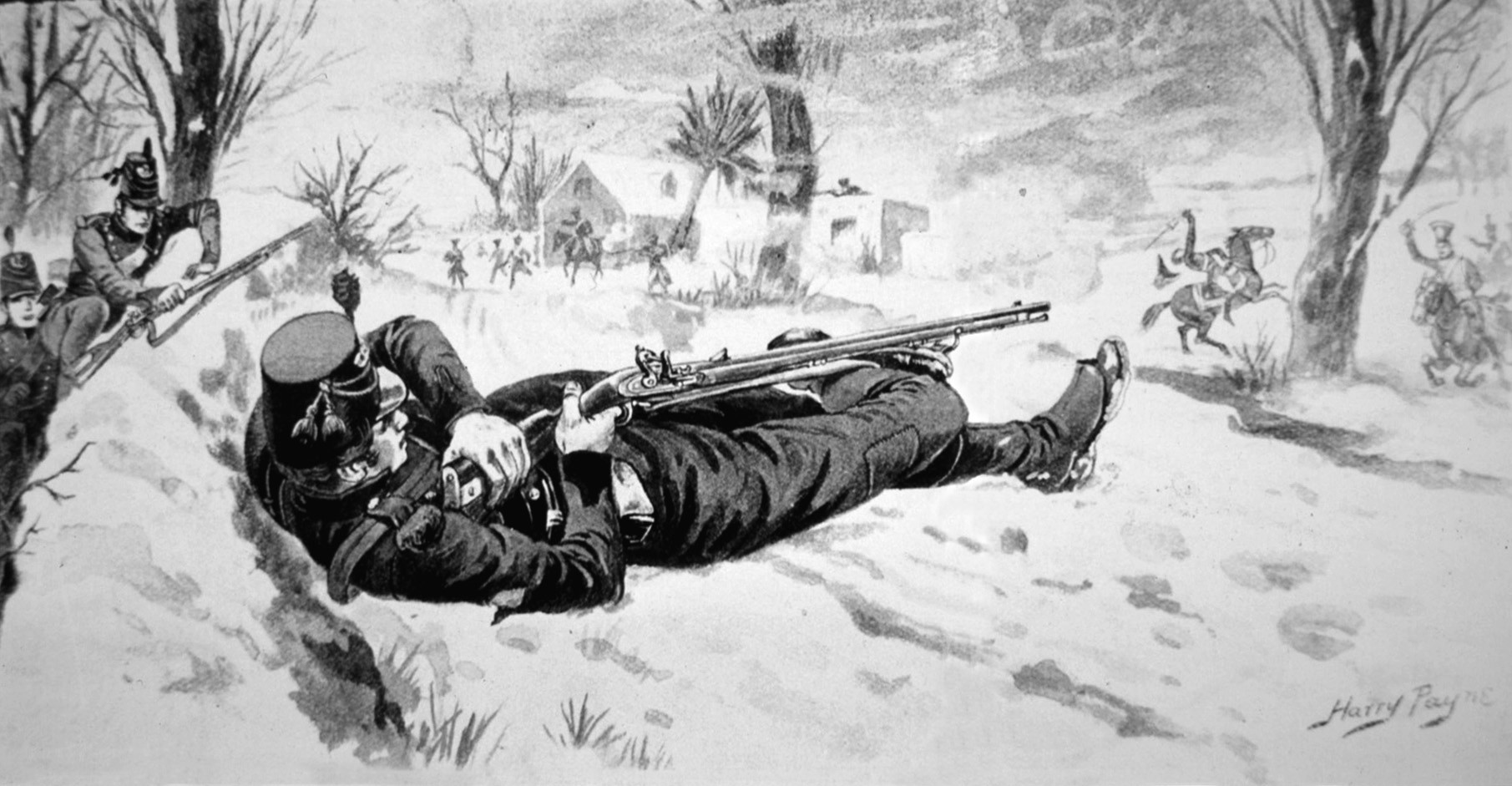

The length of the barrel was uppermost in Manningham’s mind, and he cautioned Baker not to deviate from the 30-inch length when the gunsmith suggested creating a longer barrel for accuracy’s sake. Manningham wanted his sharpshooters to be able to take full advantage of the terrain during combat, and this meant that some shooting would have to be done from the prone position. He knew from previous experiments that a short barrel would allow this firing technique, which was not possible with a regulation-length musket.

Sword Bayonettes Were Added to Rifles For Close-Quarter Combat

Baker’s first model had a Jaeger-type folding-back sight. A standard 6-inch-long lock mechanism and swan neck cock (found on the Brown Bess) was also included. It had a scrolled brass trigger guard to help insure a firm grip, and a raised cheek-rest on the left of the butt for additional support when aiming. The gun was 45 inches long and weighed almost nine pounds. With prompting from Manningham, the new rifle was fitted with a bayonet specially designed by the Birmingham sword cutler Henry Osborn. Following the German style, a 24-inch-long sword bayonet, which could be clipped onto a metal bar attached to the muzzle, was provided. The sword bayonet made the weapon awkward to manage, but Manningham felt that one was necessary. Riflemen were sharpshooters and not to be employed as close action troops, but hand-to-hand fighting and threats from cavalry could occur, and a weapon of last resort, the bayonet, was essential for protection. Since the rifle was 13 to 20 inches shorter than the average infantry musket, the additional length provided by the sword bayonet would give the riflemen a better chance to survive close-quarters combat.

Although based on the German hunting rifle design, Baker’s creations were not meant to have the same inherent characteristics as a Jaeger piece—light weight, smaller ammunition load, easily broken design. On the contrary, the Baker Rifle was meant to be a mass-produced product, taking a fairly standardized military-caliber ball, with a comparable rate of fire to its military smoothbore counterparts. The new rifle also had to be robust enough to act as a deadly club in the hands of a soldier, and to hold a bayonet.

Baker Rifles (officially referred to as the “infantry rifle” to distinguish it from the model “cavalry rifle” with slightly smaller bore, made around the same time) was delivered to the Army in September 1800. By year’s end, some 1,103 rifles had been sent to the military for its approval, while the next 12 months saw an additional 1,240 rifles produced. Most of the weapons, designated the Pattern 1800 Baker Infantry Rifle, were not finished products when they reached Army inspectors. Many were without barrels, locks, or bayonets. In order to be finished, they had to be sent to civilian contractors for completion. In fact, many of the Baker rifles produced between 1800 and 1815 were not even made by Ezekiel Baker. Early on he subcontracted with over a score of other British gunmakers to supply many of the parts that made up his rifle.

Regiments of Foot take aim with their Baker Rifles.

By early 1802, the Rifle Corps had been equipped with some 635 Baker Rifles. Although generally pleased with the gun’s performance, it was not long before the Army demanded certain modifications to be made, thus creating new models. A Pattern 1801 West India Rifle was built, essentially a cheaper gun that could stand up to the harsh tropical conditions of the West Indies. Its cost was a little over two pounds sterling, against the 1800 Model that cost almost five pounds sterling. Over 2,000 completed rifles of this type were produced and delivered to the Army.

The Longest-Serving Life of any Rifle in the History of the British Army

Starting in 1805, the government adopted an “open contact” policy for those who wanted to supply it with Baker Rifles. This allowed for more competition and a slightly lower price. That year 1,353 infantry rifles were manufactured. The Model 1805 differed from previous Baker Rifles in the size of the butt box and the presence of a slit in the underside of the forestock. About 19,000 of these were produced by 31 different contractors (13 in London and 18 in Birmingham) over the next decade.

During the first 15 years of its production (1800 to 1815), the Baker rifle was a boon to British gun manufacturers. Prices charged for materials or labor were not uniform but differed depending on where the material was obtained, or on where the various assembly points were located throughout the country. Parliamentary rules to standardize costs for purchases of the weapons were usually not enforced due to the exigencies of the ongoing war with France. The three basic patterns of the Baker Rifle were the second costliest small arm produced by the British (the cavalry carbine was the most expensive).

The vast majority of the new weapons went to what were considered the elite units of the armed forces. Among these were the 1st, 4th, and 6th Battalions of the 60th Regiment of Foot, which served in Ireland, the West Indies, South Africa, and the Iberian Peninsula. The even more famous Rifle Corps, created in 1800 and renamed the 95th Rifle Regiment in 1802, did excellent service in the Duke of Wellington’s Portuguese, Spanish, and French campaigns between 1808 and 1814. Five companies of the 95th fought at the Battle of New Orleans, and elements of battalions did yeoman service at Waterloo. In addition, thousands of Baker Rifles were supplied to Allied forces who fielded sharpshooter units like the 95th. The most noted of these were the Hanoverian raised King’s German Legion and the British trained battalions of Portuguese light infantry known as Casadores.

The Baker Rifle’s effectiveness in the Napoleonic Wars was due to its long range, accuracy and dependability under extreme battlefield conditions. The fact that the French never deployed riflemen in any great numbers was another reason why the British were able to blunt their opponents’ skirmisher tactics and impose their own will on the enemy. Along with its claim as being the best infantry flintlock, muzzle-loading rifle ever made, the Baker also has the distinction of having the longest-serving life of any rifle in the history of the British Army. First produced in 1800 it was still being issued in 1841, four years after it was taken out of production.

Thanks for a great write up on our history. The esprit de corps of the Rifles takes its heritage from these formative years and makes us crack shots today.

There are no target results from the Baker trials ? That would be interesting to see if it were truly accurate or just an improved volley of the Brown bess at a greater distance .

Considering Rifleman Plunkett was able to shoot General Colbert dead at 700 yards, and them kill his ADC with the next shot, as the ADC rode to give aid to his General, I think we can safely say that the Baker Rifle was a spectacularly accurate weapon.

I have been assured that Plunketts’ shots never happened at the ranges quoted and that the Baker rifle[which this man owns] were not accurate over 250 yards.

I have had a couple of arguments over this