By Ludwig Heinrich Dyck

In the village of Seiferdau, Southern Prussia, an eight-year-old boy with an umbrella jumped out of a second-story window. The umbrella turned inside out, the boy landed in a flowerbed and broke his leg. That little boy who dreamed of becoming an airman was Stuka ace Hans Ulrich Rudel. Rudel’s journey to fulfill his dream would not be easy, ultimately earning him the highest decoration of any German serviceman in World War II. Adhering to his maxim, “He is only lost who gives himself up for lost,” Rudel faced death untold times.

Son of a Lutheran pastor, Rudel was born on July 2, 1916, in Konradswaldau in Lower Silesia. Not much of an academic achiever, Rudel focused instead on sports. He taught himself to ski at 10, the mountains holding a special place in his heart. With family finances allocated to his sister’s medical studies, Rudel gave up his dream of civil air pilot training. He had decided to become a sports instructor when fate intervened with the creation of the Luftwaffe.

Rudel gained admission into the Wildpark-Werder Military School in 1936. Although wanting to become a fighter pilot, Rudel volunteered for the new Stuka diver bomber formations to avoid assignment to the slower bomber command. Rudel’s sober, milk-drinking habits ostracized him from the hard-partying pilot culture. Being only an average pilot did not help either. Relegated to aerial photography during Germany’s invasion of Poland, Leutnant Rudel nevertheless earned the Iron Cross Second Class. While Stukas blitzed across France, Rudel was training pilots. During the Balkan campaign, Rudel, by then an oberleutnant, was stuck at Reserve Flight in Graz when aerial brilliance came upon him. Rudel’s Stuka stayed attached to his wing leader like “an invisible tow rope,” hardly ever shot wide at bombing or missed at gunnery. Preconceptions nevertheless followed him to Greece. Forbidden to fly in combat, Rudel listened to the “music of the engines” roaring off to Crete.

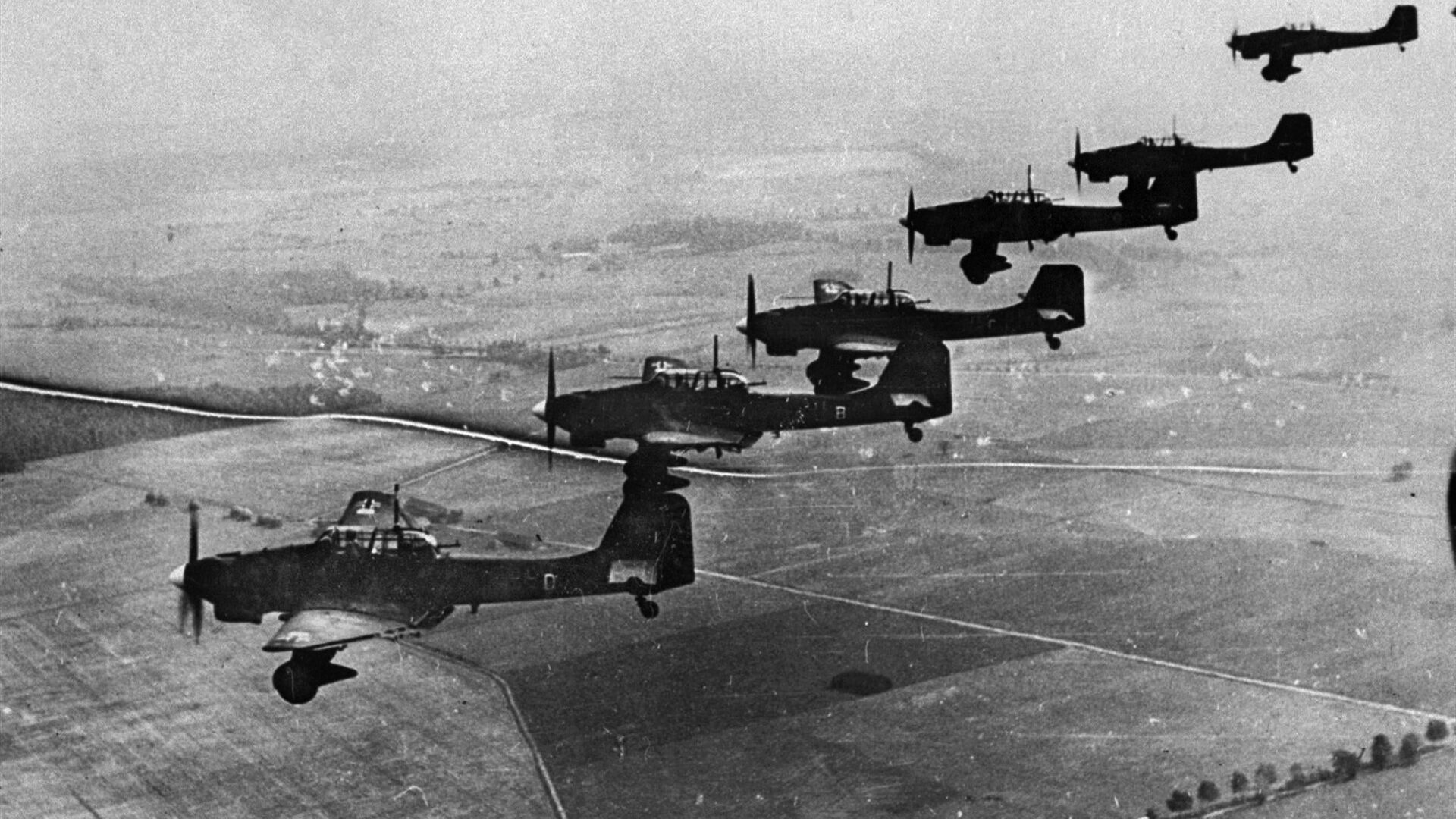

Rudel’s talents were given a chance after Germany attacked the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941. From 3 am to as late as 10 pm, Rudel was in the air over Belorussia. With sirens screaming, the Ju-87 Bertha Stukas turned Soviet supply columns into “seas of wreckage.” Rudel found a kindred spirit in Hauptman Ernst Siegfried Steen of Group III Stuka Geschwader 2, the Immelmann Wing, named after the German World War I ace. Steen affectionately called Rudel that “crazy fellow” because Rudel, who received the Iron Cross First Class on July 18, flew dangerously low for accuracy.

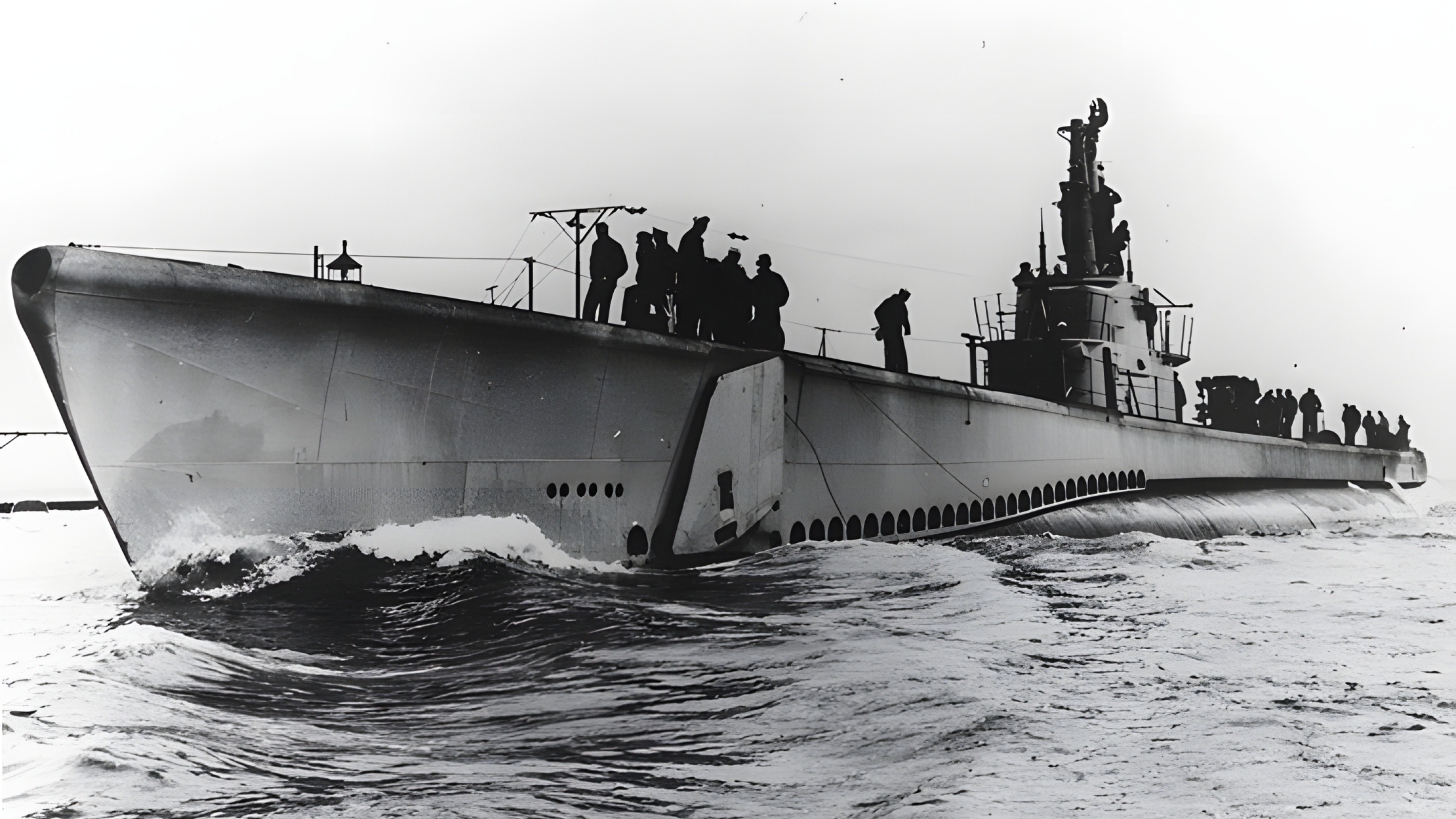

The Immelman Wing next joined the siege of Leningrad where on September 16 the Stukas caught the 23,500-ton Soviet battleship Marat in open water. Steen’s bomb was a near miss but Rudel’s 1,000-pound bomb was dead on. When it was confirmed that the Maratsurvived, Rudel saw red. Braving enemy fighters and the antiaircraft fire of Kronstadt harbor bursting “like the clap of doomsday,” Rudel returned to finish off the wounded Maraton the September 23. Absorbed with hitting his target, Rudel released his new 2,000-pound bomb at 900 feet, forgetting that its fragmentation effect ranged up to 3,000 feet. Rudel momentarily blacked out, skimming 10 feet above the water. Rear gunner Alfred Scharnovski woke him up: “She is blowing up, sir.”

Rudel spent the winter of 1941 in the Rzhev sector. Weakened by lack of winter supplies, frozen petrol, and frostbite, the German soldiers held out against an onslaught of fresh Siberian divisions. Not for the last time, the Stukas defended their airfield from ground attacks. Rudel’s holiday present was the German Cross in Gold followed in January 1942 by the Knight’s Cross. Temporarily sent to reserve flight at Graz as an instructor, Rudel stopped on the way to get married in his home village.

Rudel’s new crews underwent rigorous aerial training, supplemented with morning runs and afternoon swims. Rudel volunteered his trainee Staffel (squadron) to support mountain troops in the Caucasus. Flying over the snowcapped Elbruz Mountains, Rudel was entranced by green meadows and mountain flowers. “For a time I forgot entirely the bombs I am carrying and the objective.”

In September 1942 Rudel completed his 500th operational flight. Reaching his 600th in November, Rudel celebrated by consuming copious amounts of cake. Soon after Rudel contracted jaundice. Ignoring a furious doctor, Rudel staggered from the hospital to take command of 1st Staffel of the Immelmann Wing at Stalingrad. By now the wing had been re-equipped with the more powerful Ju-87 Dora. The close-quarter fighting in the city demanded painstaking accuracy to avoid hitting friendly troops. Overexerted and sick, Rudel pushed himself to the limits to ward off the destruction of the 6th Army, feeling “more as if I were in Hades than on earth.”

On February 10, 1943, Rudel completed his 1,001st operational flight. Promoted to flight lieutenant, Rudel was sent on holiday leave. After captaining the Luftwaffe team in a ski tournament in Austria, a recharged Rudel went on to test the new twin 3.7cm cannon-armed Ju-87 Gustav Stukas. Even slower and less maneuverable than the bomb-carrying Ju-87, the Gustav nevertheless became an excellent tank buster. Resuming command of 1st Staffel, Rudel integrated the cannon Stukas in the fighting for the Kuban bridgehead. Within a few days Rudel himself destroyed 70 of the small Soviet boats trying to cross the lagoons. His efforts earned Rudel the rank of Hauptmann on April 1 and the Oak Leaves on April 14.

In July 1943 the Stukas unleashed a storm of destruction at the Battle of Kursk. Swooping in at 15 to 30 feet above the ground, Rudel’s cannons blasted tungsten-core shells through the thin back armor of enemy tanks. A successful hit entailed flying through an exploding curtain of fire, scorching Rudel’s Stuka and riddling it with splinters. By the end of the first day’s attack, Rudel’s Gustav had destroyed 12 tanks. Other Doras bombarded the deadly Soviet antiaircraft guns or circled to protect against fighters. Despite inflicting heavy casualties on the Soviets, the Germans gained little ground. Worried about Anglo-American landings in Sicily, German leader Adolf Hitler called off what turned out to be Germany’s last great offensive in the East.

On July 17 Rudel took over command of Group III Stuka Geschwader 2, helping slow down the Soviet advance that pushed the Germans to the Dnieper River by August. After destroying his 100th tank, Rudel received the Swords to his Knight’s Cross at Hitler’s Wolf’s Lair on November 25.

Rudel’s Stukas were transferred north from the southern front to aid the encircled Cherkassy pocket, then back south to north of Odessa. Promoted to major on March 20, 1944, Rudel led an attack against a Dniester bridge. A new pilot lagged behind and, riddled by Soviet Lag-5 fighters, veered off into Soviet territory. Rudel found the crew in a field waving from beside their downed plane. Landing to rescue them, Rudel’s own plane got stuck in the mud. Pursued by Soviet infantry, Rudel and his companions ran four miles to the Dniester. Confronted by a steep cliff overlooking the river, the four of them slid downhill through thorny bushes. Their clothes and hands ripped, they caught their breath before diving into the icy, flooded river. Reaching the other side, the crew of the other Stuka collapsed beside Rudel. Hentschel was missing. Rudel, himself exhausted, dove back in. He was too late: “If I had succeeded in catching a hold of Hentschel I should have remained with him in the Dniester.”

Rudel and his companions next stumbled upon another party of Russians. Tommy guns pointing at them, his companions surrendered. Dodoging bullets, Rudel made a break for it. Hit in the shoulder, Rudel nearly blacked out. More Russians with horses and dogs came after him. Cresting a hill, he ran down the other side, collapsing in the mud. In the twilight, the pursuers lost of sight of Rudel. He plodded on through pouring rain, running mile after mile, losing all feeling in his feet. Aided by Romanian peasants who shared their meager food, Rudel crossed 30 miles of enemy territory in “the hardest race of [his] life.” The elation of Rudel’s return among the Immelmann Wing was tempered by the news of Hentschel’s death.

On March 29, Rudel initially refused the Diamonds to the Knight’s Cross because Hitler also insisted that Rudel stop flying. To Rudel’s relief, Hitler rescinded his order.

More special awards were to come, along with more attempts to ground Rudel and have him command increasingly fanciful operations. Clad at one meeting as a medieval archer, at another in a toga, the eccentric Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring awarded Rudel with the Golden Pilot’s Medal with Diamonds and the Golden Front Service Medal. The latter featured the number of Rudel’s 2,000 sorties in diamonds. Göring wanted Rudel to lead a new Messerschmitt 410 squadron to combat Anglo-American bombers. The Reichsmarschall also spoke of an unbelievable 300 panzers ready for an imminent Eastern offensive. Furthermore, worried about Rudel’s safety, Göring relayed Hitler’s forbiddance of Rudel rescuing any more downed crews.

Even as the Soviets pressed closer to the German homeland, Rudel experienced the awesome might of the U.S. Air Force. Large numbers of American fighters hunted for prey after escorting bomber formations. Rudel remembered several hundred Mustangs pouncing on his 19 Stukas. For the first and only time, Rudel abandoned the mission but managed to bring his squadron home without loss.

The Soviets encroached upon East Prussia, where Rudel disobeyed orders and rescued another crew. In recognition of Rudel’s defense of the Latvian Courland pocket, Field Marshall Ferdinand Schoerner sent cakes decorated with the number of Rudel’s destroyed tanks. In heavy fog, Rudel’s Stuka suddenly buzzed right over a massive Soviet penetration. Rudel twisted crazily to avoid the metal screaming past him from antiaircraft and machine-gun fire. Rear gunner Ernst Gaderman yelled; “Engine on fire!” Oil and flames obscured the cockpit. Rudel crash-landed in a forest. Gaderman, a doctor, suffered three broken ribs but managed to remove a piece of metal skewering Rudel’s thigh. Despite his injuries, including a concussion, Rudel returned with his squadron to lay waste to the Soviet column.

Flying back to Romania, Rudel discovered that his allies had changed sides when Romanian anti-aircraft fire opened up on the Stukas. Rudel threatened to bomb the staff headquarters of Romanian Air Force Commodore Emanoil Ionescu, who promptly allowed the Stukas to continue using the airfield. Assuming command of the Immelmann Wing, Rudel defended the German Army’s retreat out of Romania into Hungary. He alternated between flying the Ju-87s or the new, faster ground attack FW-190Fs. In September 1944, Rudel returned to inspect a new type of Soviet tank destroyed in an earlier battle. Survivors hidden in the wreckage opened up on the Stuka with their antiaircraft gun, puncturing Rudel’s leg. Passing out after landing at Budapest, Rudel woke up in the hospital with an extracted bullet and a plaster cast.

Cutting short his six-week recovery to eight days, Rudel joined the battle for Budapest. Summoned to Germany again, Rudel met not only a beaming Göring but Hitler alongside most of the high command. Awarded with the unique Golden Oak-leaves with Swords and Diamonds to Knights’ Cross on January 1, 1945, Rudel was promoted to colonel but was again ordered to stay grounded. Again Rudel refused to accept the decoration if it meant he could no longer flying. Hitler’s faced darkened then changed to a smile, “All right, you may go on flying.” Returning to Budapest, Rudel earned the Hungarian Medal for Bravery from the Hungarian leader Ferenc Szalasi.

Ignoring more orders to discontinue flying and disciplinary threats, Rudel helped Schoerner build up a new front in Silesia, and he also assisted Reichsführer SS Heinrich Himmler in defending Pomerania and Frankfurt on the Oder. Rudel destroyed 12 of 13 tanks a mere 50 miles from Berlin. With one cannon jammed and a single round remaining in the other, Rudel went for the remaining Stalin tank which “burst into a blaze” when “something seared through” Rudel’s “leg like a strip of red hot steel.” Rudel again passed out after landing his flaming Stuka.

Rudel awoke on an operating table at Seelow, one of his legs in plaster, his other leg amputated. Rudel consoled himself with memories of comrades who had paid the ultimate price. Deluged with flowers and presents from an adoring public, Rudel barely recovered in Berlin’s Zoo bunker before returning to fly in April. His mechanics rigged up a projection to control the rudder bar with his stump but the rubbing re-opened the wound, splattering the engine in blood.

By now even Rudel questioned the sanity of his high command. Holding out for an armistice with the Western Allies, Rudel frankly told Hitler that “the war can no longer be ended victoriously on both fronts.” Rudel kept flying until May 8, 1945 when he received the news that the war was over. He was to surrender unconditionally to the Russians. Considering a suicide attack, Rudel was dissuaded by his men. Addressing his Immelmann Wing, Rudel praised the men’s bravery and loyalty.

Anticipating a chivalrous reception, Rudel crash-landed at an American aerodrome at Kitzingen during parade formation. Rudel was greeted by a soldier pointing his gun and demanding Rudel’s Oak Leaves. Rudel “shoved him back and shut down the hood again.” Rudel remained undaunted in captivity. He denied knowledge of death camps, retorted with accusations of women and children massacred by Allied bombers, and told the Americans to look for further atrocities among their Soviet allies. Deemed a “typical Nazi officer” by his interrogator, Rudel was interned at U.S. Army bases and prisoner of war camps in Germany and France. Transferred to a German hospital Rudel obtained his release in 1946.

Sick of a Germany that blamed the ills of World War II on its soldiers, Rudel moved to Argentina in 1948. He worked for Argentina’s airplane industry and helped build the air force of President Juan Peron. But his real passions continued to be sports and mountain climbing, and he did not let his prosthetic leg deter him. Rudel competed in skiing and tennis and nearly climbed the summit of Aconcagua, the highest peak in the Americas in 1951. During 1953-1954, Rudel joined fellow veterans on the Argentina-Chile border in ascending the formidable 22,441-foot Llullaillaco. Rudel’s mountaineering adventures are recounted in his book, From the Stukas to the Andes.

On a visit to Germany in 1950, Rudel divorced his wife, who had refused to follow him to Argentina with their two children. She had sold Rudel’s medals, including his Knight’s Cross with Diamonds, to an American collector. Rudel continued to do well in his professional life as a representative for Siemens and other manufactures.

But controversy continued to follow him. With the help of Paraguayan President Alfredo Stroessner, Rudel protected notorious war criminal Josef Mengele for three decades. But Mengle was not fond of Rudel, comparing Rudel’s opinions to the “stupid [anti-Nazi] material pouring down on young Germans since 1945.” Rudel nevertheless advocated renewed aggression against the Soviet Union and derided members of the German Army who failed to fully support Hitler. Returning to live in West Germany, Rudel joined the right wing German Reich party. In 1976 Rudel’s acceptance to an officer’s evening of the Immelmann Wing caused a stir in the Bundeswehr because of Rudel’s “activity in a neo-Nazi party.”

Rudel was not destined to have a long life, succumbing at the age of 66 to a brain hemorrhage on December 21, 1982. Buried in Dornhausen, Rudel’s funeral was attended by old comrades, some wearing the Knight’s Cross, some giving a last Hitler salute.

Rudel’s bravery, skill, self-sacrifice, and nearly boundless endurance cannot be denied. Rudel risked his own life six times to rescue downed comrades. He himself was shot down 30 times by flak, never by an enemy plane. During his 2,530 combat missions, unmatched by any pilot, Rudel single-handedly destroyed 547 tanks, 2,000 ground targets, the Soviet battleship Marat, two cruisers, and a destroyer. Stalin put a ransom of 100,000 rubles on Rudel’s head. Schoerner did not exaggerate much when he praised Rudel as being “worth an entire division.”

In his riveting war memoir, Stuka Pilot, Rudel comes across as a likable, heroic, and inspiring figure. Rudel’s noble characteristics are difficult to reconcile with his close association to Hitler’s clique and to far-right causes after the war, but Rudel was never accused of any war crime. Indoctrinated in Nazi ideology at an early age, he clung faithfully to what he deemed righteous and either disbelieved or ignored its horrific consequences. Perhaps British fighter ace Douglas Bader, who did not agree with a number of Rudel’s beliefs, best summed up Rudel, concluding that he was “by any standard, a gallant chap.”