Fifty-two submarines of the United States Navy were lost while on patrol during World War II. The circumstances surrounding the losses of some of these have been well documented. For others, their locations and the events that led to their sinkings have been shrouded in the proverbial fog of war.

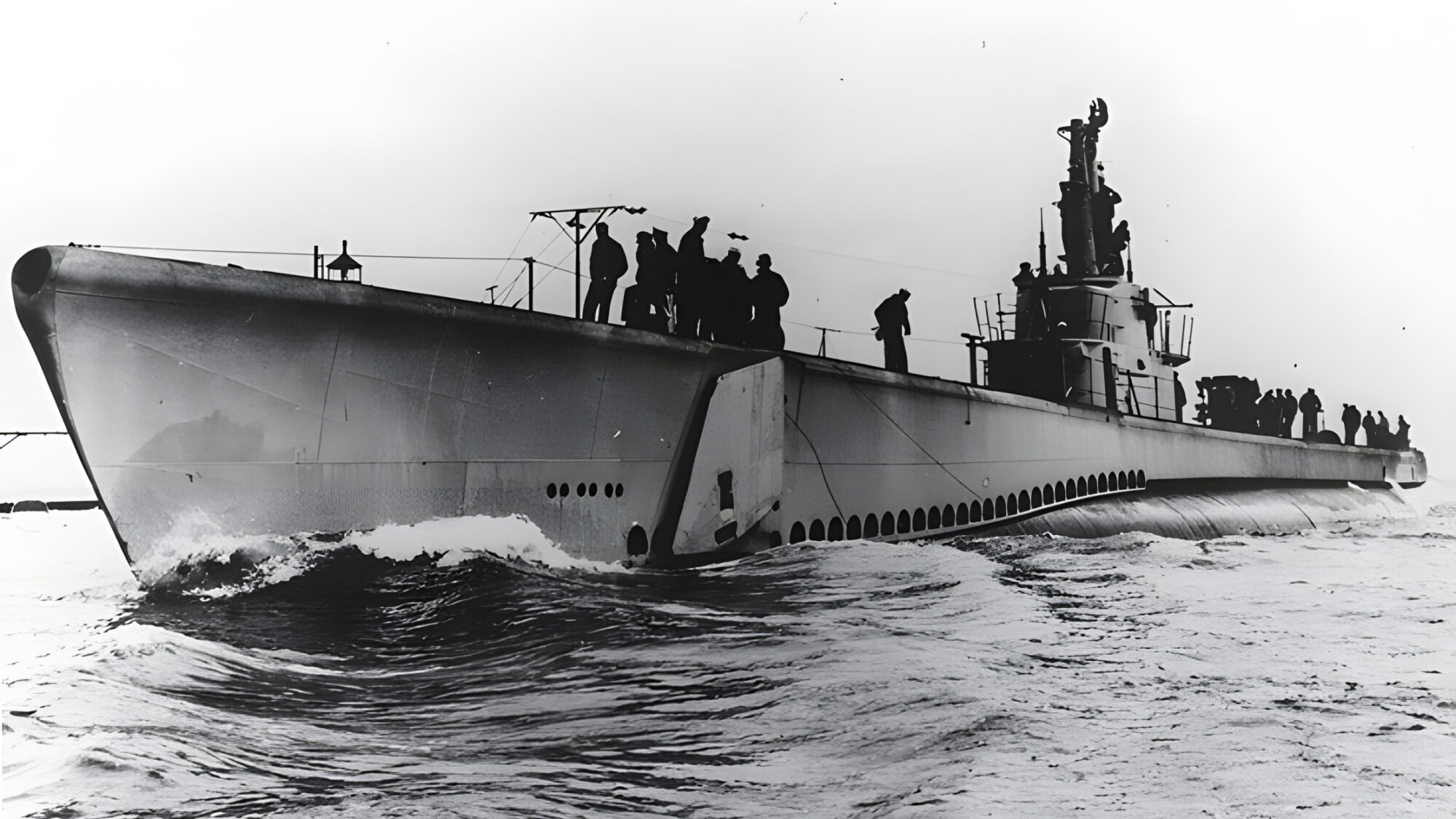

For one of those submarines on eternal patrol, the book is now closed. Assumptions are confirmed, and after six decades of uncertainty the families of 86 sailors know the final resting place of their loved ones. USS Lagarto (SS 371), a Balao-class submarine on patrol in the Gulf of Thailand, was last heard from on May 3, 1945, as she prepared to attack a Japanese convoy.

In 2005, a British diver reported discovering the wreckage of a submarine sitting upright in 225 feet of water off the coast of Thailand. While it appeared very likely that the Lagarto had been located, the U.S. Navy endeavored to make its own positive identification. A great deal of research and preparation, including a visit to the USS Torsk, a sister of Lagarto that is now a floating museum in the Inner Harbor of Baltimore, were undertaken before the salvage ship USS Salvor headed to the site. During six days of diving, 500 digital photographs and 10 hours of video of the wreckage were taken.

Divers had been briefed to look for a twin five-inch gun mount, a starboard anchor, and the propeller where the name of the submarine might be engraved. They found the gun mount and the anchor hanging to starboard. In addition, after scraping away decades of coral and marine growth, the letters “LA” were revealed on the propeller.

Lagarto was one of 28 submarines built in Manitowoc, Wisconsin, and the city’s name was completely visible on the propeller as well. Three other Manitowoc-built submarines, USS Golet, USS Kete, and USS Robalo, were lost during the war. None of these was in action near the location of the wreck.

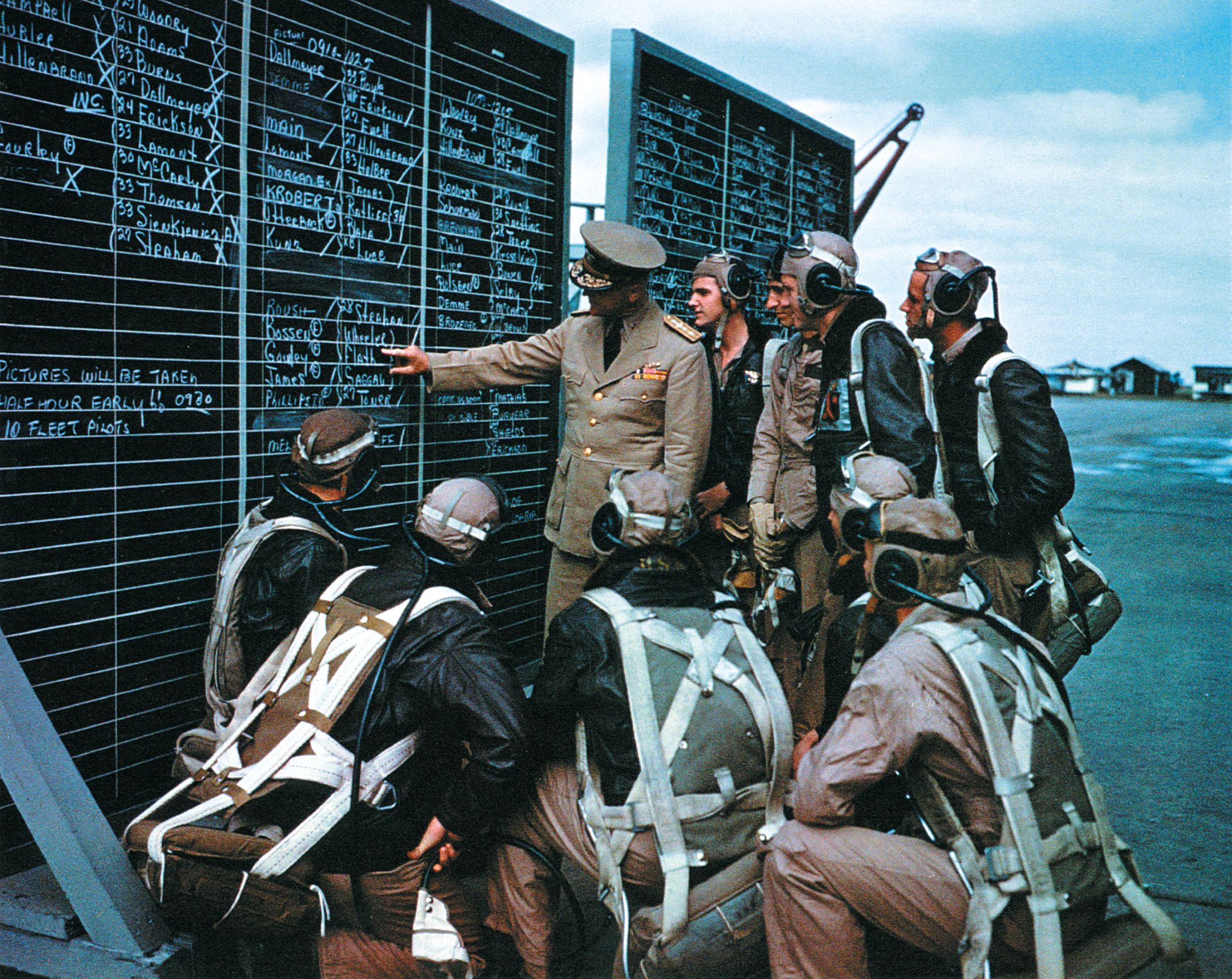

Navy records indicate that the USS Lagarto left Subic Bay in the Philippine Islands on April 12, 1945. Her skipper, Commander F.D. Latta, received orders to proceed to the Gulf of Thailand on April 27. This was the second war patrol for the submarine, having operated against Japanese picket boats in the Nansei Shoto islands. On her first sortie, Lagarto had sunk the Japanese submarine RO-49 on February 24, 1945, and participated with the submarines Haddock and Sennet in attacks against enemy surface ships—sharing credit for sinking two of them.

On the fateful morning of May 3, 1945, Lagarto made contact with another submarine, USS Baya, to coordinate an attack against the enemy convoy which included at least one tanker, an auxiliary vessel, and two destroyers. Persistent attacks were driven off by radar-equipped escort vessels. Baya withdrew, and there was only silence from Lagarto. Japanese records indicate that the minelayer Hatsutaka reported sinking an American submarine in the area, and it can be concluded with certainty that this attack was the one that doomed Lagarto.

Initially, a wreath was dropped into the ocean above the wreck site. On the final day of diving, a brass plaque was affixed to the submarine’s capstan. Crewmen of the USS Salvor conducted a memorial service and read letters from family members of the lost Lagarto sailors.

“We owe a great debt to these men, and to all of the World War II submariners,” remarked Rear Admiral Jeffrey B. Cassias, commander of the U.S. Pacific submarine force. “In the world’s darkest hour, they faced the greatest risks and demonstrated the most noble courage to preserve the freedom of our nation.”

The final resting place of Lagarto and her crew is one of many war graves scattered across the globe. Certainly, there are many more such dark and silent locations, on land and sea, that are yet to be discovered.

Michael E. Haskew

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments