By William E. Welsh

In the valley south of the hill known in Czech as Bitna Hora, a vast host assembled by the Austrian Hapsburgs advanced toward the ranks of the Protestant rebels blocking the path to Prague, the capital of Bohemia. A sea of red, green, yellow, and gold banners representing the Catholic forces of southern Europe hovered over dense blocks of foot soldiers and horsemen. Men from Austria, Germany, Spain, Italy, Burgundy, and Flanders tramped toward the enemy.

The foot formations were the vaunted tercios, composed of hundreds of men in deep files and broad rows that seemed to swallow the tall grass and fallow fields through which they tramped. In the center of the tercios were armor-plated pikemen carrying 15-foot, steel-tipped pikes that rose in chorus toward the heavens. Musketeers armed with muzzle-loading muskets swarmed the front and sides of the tercios. To the left and right of the sea of foot soldiers, iron-breasted cuirassiers armed with razor-sharp sabers sat astride powerful war horses.

From the relative safety of the rear of the army, Duke Maximilian I of Bavaria and Lt. Gen. Johann Tserclaes, the Count of Tilly, watched the advance. They were proud of the army that advanced before them, and they had every expectation of victory that crisp autumn day. The time had arrived to send the Protestant heretics to Hell and restore the Catholic Church to its rightful place as the true religion of Christian Europe.

The first phase of the Thirty Years War involved the struggle for control of Bohemia between the Protestant Bohemians and the Catholic forces of deposed King Ferdinand of Bohemia, who belonged to the powerful Austrian branch of the House of Hapsburg. The seeds of the conflict lay in the emergence of Lutheranism and Calvinism in the first half of the 16th century.

At the beginning of the 17th century, Lutheranism flourished in northern Germany and Scandinavia. Although Calvinism was practiced widely in the United Provinces, beyond that it existed in scattered enclaves throughout Europe. All things considered, the Roman Catholic Church still had a firm grip on southern Europe.

In the early 16th century, the Bohemians had elected a Hapsburg prince as their king largely for protection against the continuing menace posed by the Ottoman Turks. In so doing, they made Bohemia a constituent state of the Hapsburg dynasty. The Hapsburgs welcomed Bohemia with open arms in large part because it had considerable wealth derived from agriculture and commerce. The Kingdom of Bohemia comprised not only the province of Bohemia, but also the provinces of Silesia, Lusatia, and the margravate of Moravia.

The Austrian Hapsburgs at the time also controlled the imperial crown of the Holy Roman Empire, a loose confederation of semiautonomous territories established in 962 by German King Otto I. The empire was ruled by secular kings, archdukes, dukes, princes, and counts, as well as by ecclesiastical officials. It covered so many lands and peoples that the territories hardly ever came together for the common good. The emperor was elected by seven powerful elector princes, three of which were ecclesiastical princes (the archbishops of Mainz, Trier, and Cologne), and four of which were secular princes (Saxony, Brandenburg, Palitinate, and Bohemia).

The health of 61-year-old Holy Roman Emperor Matthias was deteriorating rapidly in 1618, and the Hapsburgs were poised to advance a new candidate for the imperial throne. In addition to holding the imperial title, Matthias also was the king of both Germany and Bohemia and the archduke of Austria. The leading candidate to succeed him was his cousin Ferdinand, Archduke of Styria, a Jesuit-educated conservative. In 1617 the Bohemian Diet had elected Ferdinand to succeed Matthias upon his death.

The Long Turkish War of 1593-1606 caused widespread epidemics and famine in Hungary, and in the aftermath Stephen Bocskay, the Calvinist prince of Transylvania, led a rebellion against the Holy Roman Empire and invaded Moravia. As part of the peace deal brokered in its aftermath, the Hapsburgs granted full religious liberty to the Hungarian people. When the Bohemian Diet learned of this, it demanded the same freedom of worship. The Letter of Majesty of 1609 allowed the Bohemians to worship God as they chose. Fearing that the Hapsburgs might renege on the agreement, the Bohemian Diet established an official body called the Defensors to protect this right.

In the years preceding Matthias’s death in March 1619, there was considerable anxiety among Protestants who feared that Ferdinand would dispense with the Letter of Majesty. Subsequent events would prove them right.

Ferdinand was shrewd, bold, and zealous. Because he wanted to prove to Europe that he was willing to take a hard line against the Protestants, he banished Protestant clergy and school teachers from his duchy when he assumed control of it in 1596. He also ordered the destruction of Protestant churches throughout his duchy.

In addition to Ferdinand, the Hapsburg king of Spain also had a claim to the imperial crown. In 1617 Ferdinand entered into a secret pact with King Philip III of Spain whereby Philip would support Ferdinand’s bid to become emperor in return for the transfer of the province of Alsace and various imperial fiefs in Italy from the Austrian Hapsburgs to the Spanish Hapsburgs.

Before the Bohemians crowned Ferdinand as their king, they inquired as to whether he would honor the Letter of Majesty. Although he secretly had no intention of honoring the agreement, he said he would. He appears to have justified this falsehood on the grounds that he might be in a better position to mediate the matter with the Protestants after he was crowned.

In early 1618 Ferdinand’s Council of Regents in Bohemia, which consisted of five leading Catholics appointed to conduct the day-to-day business of the kingdom while Ferdinand remained at Graz, informed him that Protestants were building two churches on lands belonging to the king or that had an effect on the king’s property. At Klostergrab, a village close to the border of Saxony that belonged to the Archbishop of Prague, Protestants were constructing a church. They maintained that they had the right to build their church because they were freemen and not the archbishop’s vassals. And at Braunau on the Bohemian-Silesian border, another group of Protestants also was building a church. In the process, the Protestants allegedly stole construction materials from an adjacent monastery. The Council of Regents found grounds to oppose both churches. In the Braunau case, they even arrested and jailed some of the Protestants.

The two cases had both political and religious implications. The Defensors took up the two cases. They held that Ferdinand’s officials had overstepped their bounds and that the churches were protected under the Letter of Majesty. They demanded that Ferdinand’s regents release the Protestants imprisoned in the Braunau case.

Count Matthias Thurn, a Protestant Bohemian noble who had served as a colonel in the Imperial army, convened a meeting in Prague on May 22 at which the Defensors and other prominent Protestants discussed the situation. Thurn suggested that they march on the royal palace and depose the Hapsburg officials.

The following day Thurn and the Defensors stormed into the royal palace in Prague. They seized two regents on duty at the time, Count Slavata and Count Martinice, and threw them out of the window of their palace office. Fortunately for the two regents, they landed in a pile of waste and rubbish in the palace moat and avoided serious injury. The incident, known as the Defenestration of Prague, led to preparations for war by both the Protestant Bohemians and the Catholic Hapsburgs.

In the wake of the Defenestration of Prague, the Protestant leaders of Bohemia moved to depose Ferdinand on the grounds that he had misrepresented himself to them. They believed that Frederick not only threatened their religious freedoms, but also their civil liberties. The Bohemian Estates appointed a search committee and tasked it with finding a Protestant prince to replace Ferdinand as king of Bohemia.

The leading contender was 22-year-old Frederick, the Calvinist Elector Palatine and leader of the Protestant Union. The most prominent of the four secular electors controlled both the wealthy Lower Palitinate along the Upper Rhine River and the less wealthy Upper Palitinate adjacent to the east. Frederick was amiable and outgoing, but he lacked the skills necessary to lead a kingdom in time of war.

The best thing that Frederick had going for him was that his polished chief councilor, Prince Christian I (the Elder) of Anhalt-Bernberg, was an accomplished statesman and widely respected by Europe’s leading Protestant princes. Anhalt’s grand ambition was to create a political network of strong Protestant allies capable of countering the enormous power of the Hapsburgs and the Counter Reformation. Anhalt’s greatest political achievement was establishing the Protestant Union in 1608, which had been followed the next year by the establishment of a Catholic League of south German princes led by Duke Maximilian of Bavaria. Maximilian was a financial wizard whose coffers were full as a result of the duke’s sound fiscal policies and financial skills.

While the Bohemians planned to raise an army, they had an immediate need for troops to counter the Imperial forces controlled by the Austrian Hapsburgs. Duke Charles Emmanuel of Savoy, who detested both the Spanish and Austrian Hapsburgs, had recently hired a mercenary general, Count Ernst von Mansfeld, to campaign against the Spanish in northern Italy. Savoy sent Mansfeld’s German mercenaries to the Lower Palatinate where they could support Frederick of Palatine if he were elected king of Bohemia.

Mansfeld was born and raised in Luxembourg in the Spanish Netherlands. In his early career, he fought in the Imperial army in Hungary. He had a falling out with Archduke Leopold V of Outer Austria, who led campaigns in the Spanish Netherlands and other theaters, which drove him into the service of the Protestant princes of Europe as a mercenary commander.

Silesia, Lusatia, and Moravia all agreed almost immediately to join the rebellion. In addition, the small population of Protestants in Austria also agreed to assist the Bohemians. The opposing forces in Bohemia and Austria began raising troops. They not only recruited on their own lands but also sought troops and money from their respective European allies.

On the Catholic side of the dispute, Ferdinand was severely hampered by his lack of funds to wage war against the rebellious Bohemians and their allies. What little funds he did have were used up almost immediately at the outbreak of war. Fortunately, the Spanish Habsburgs saw it was in their interests to back Ferdinand, who was the leading contender for the imperial title. Don Inigo Velez de Onate, Spain’s ambassador to Vienna, arranged financial support for Ferdinand and procured Spanish troops to assist the Austrian Hapsburgs in stamping out the rebellion. The support from Spain gave Ferdinand the resources needed to switch to the offensive.

As Bohemia drifted toward war, Maximilian offered to furnish troops and additional funds, but unlike the Spanish he made certain demands on Ferdinand to ensure that the emperor would eventually reimburse him. Onate arranged for Maximilian’s troops to occupy part of the Archduchy of Austria until such time as they were repaid by the emperor. Although this was distasteful to Ferdinand, he had no choice if he wanted to prevail over his Protestant enemies in Bohemia. Besides, Maximilian’s investment was enormous. The Bavarian duke, who also presided over the Catholic League, would eventually pledge upwards of 18 million florins to Ferdinand.

In September 1618 the Bohemian Estates ordered towns and villages throughout the kingdom to raise troops. The goal was to raise as many as 20,000 troops, but they only raised 12,000. Thurn was chosen to lead the weak and largely ineffective Bohemian army whose numbers made it appear strong on paper. The Bohemians failed to raise taxes effectively, and there was hardly any money to pay the troops.

The Silesians and Moravians each raised 3,000 troops, but only the Silesians joined the Bohemian army at the beginning of the conflict. In addition, the Austrian Protestants raised 3,000 troops to serve in the nascent Bohemian army.

The Imperial army was led by Charles Bonaventure de Longueval, the Count of Bucquoy, who had served as the Imperial army’s commander-in-chief since 1614. Born in Arras, Bucquoy had joined the Spanish army where he had risen to the rank of colonel by the age of 26. Bucquoy had gained extensive combat experience serving under Spanish Captain-General Ambrogio Spinola, who led the forces of the Spanish Netherlands. Assisting Bucquoy was Heinrich Duval, the Count of Dampierre, a native of France who had served in the Imperial army since 1602 and had extensive experience fighting the Turks, Venetians, and rebellious Hungarians.

Thurn massed his forces at Caslav in central Bohemia in late summer 1618. Bucquoy and Dampierre arrived in Bohemia that month prepared to assault Caslav. The arrival of 3,000 Silesians under the Margrave of Jagerndorf enabled Thurn to go over to the offensive. Bucquoy withdrew to Budweis, but not before the Austrians had pillaged 24 villages. Budweis, which was strategically located close to the frontiers of both Lower Austria and Upper Austria, would pose a perpetual problem for the Protestant army. While Bucquoy defended Budweis, Dampierre withdrew with a small force to Krems in Lower Austria.

The Bohemians continued on the offensive. Thurn took the main body of troops into Moravia to secure it. He also gave Count Heinrich von Schlick, a former Imperial army field marshal who had fought the Turks, 4,000 men to invade Austria. The first major battle of the war occurred on September 9 at Lomnice in Moravia. When Thurn’s larger Bohemian army bore down on Bucquoy’s smaller army, the Imperial commander sought to withdraw. But the Bohemians caught up with the Imperial rear guard, which touched off a nine-hour running battle that bled the Imperial army.

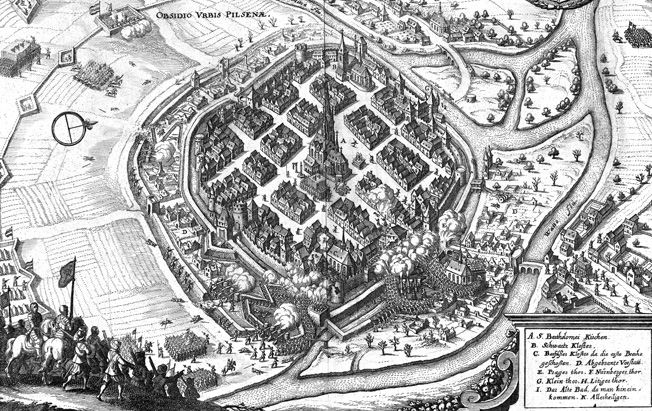

The Protestants received substantial reinforcements with the arrival in September of Mansfeld’s 4,000 troops. His command, which became known as the Bohemian Army Corps, was composed of mercenaries of many nationalities, including Germans, Dutch, Walloons, English, and Scots. He moved against Pilsen. His troops besieged the town for two months, eventually forcing a breach on November 21 and expelling the Catholics. Although there was a discussion about burning Pilsen to the ground, Mansfeld decided it was more useful as a base of operations against the Imperial army.

Although an experienced commander, Mansfeld committed a major blunder by failing to detach a force to occupy the so-called Golden Track by which supplies and reinforcements marched from Austria to Bohemia. Lt. Col. La Motte, an Imperial officer commanding 1,300 Walloon cuirassiers opened a supply line to Bucquoy at Budweis in southern Bohemia. La Motte put his men to work fortifying the corridor by building a series of blockhouses.

Ferdinand received large numbers of Spanish reinforcements in 1619. In January, Spain sent 6,000 Walloons and Germans from the Spanish Netherlands and 3,000 from Italy via the Valtelline to Austria. Spain sent another 7,000 troops from the Low Countries to Austria in July.

After securing Moravia in the spring of 1619, Thurn marched on Vienna with 9,000 men; however, he lacked siege weapons to attack the city walls. Instead, he counted on the Austrian Protestants to rise up against Ferdinand. On June 5, a group of Protestants from the Lower Austrian Estates went to the Hofburg Palace to badger Ferdinand into signing a petition.

Just as Ferdinand was on the verge of being compelled to grant concessions to them, 400 Imperial arquebusiers and cuirassiers arrived at the palace to rescue him from the clutches of the Protestants. The troops had only days before been recruited to Imperial service. Colonel Gilbert of St. Hilaire embarked his troops on barges at Krems and they sailed 40 miles downstream to Vienna, entering the city through a waterfront gate and marching immediately to the palace.

Five days later, Bucquoy’s 5,000 Imperial horse soldiers intercepted Mansfeld’s corps as it was marching to reinforce Count Georg Friedrich von Hohenlohe, general commader of the Bohemian Estates, at Budweis. In the ensuing Battle of Sablat fought June 10, the Imperialists annihilated Mansfeld’s corps. With the Imperial forces capable of attacking Prague, Thurn broke off his siege of Vienna and hastily retreated north.

Bucquoy’s victory over Mansfeld restored the morale of the Imperial army. Dampierre invaded Moravia in August but was repulsed by the Protestants. On August 26, the Bohemians deposed Ferdinand and elected Frederick of Palatine as their new king. Two days later, the electors elected Archduke Ferdinand as the Holy Roman Emperor. The majority of the electors saw the revolt as a local affair that did not have an adverse effect on their people or territories, and for that reason they decided to maintain the status quo and allow the Hapsburgs to control the Imperial crown. Catholic fortunes grew stronger when Spain, Bavaria, and Austria formally became allies on October 8 through the Treaty of Munich. On October 31, Frederick V and a long train of supporters arrived in Vienna. Count Anhalt, who arrived with Frederick, assumed overall command of the Bohemian army but retained Thurn as his second in command.

Although Bohemian King Frederick and Hungarian Prince of Transylvania and King Bethlen Gabor did not formally sign a treaty until April 1620, they began operating jointly in October 1619. Bethlen Gabor swept into Hungary with 35,000 light cavalry. After securing Pressburg, he advanced on Vienna where he planned to rendezvous with Thurn’s Bohemian army. Bucquoy, who had been planning to make a strike against Prague, countermarched to Vienna. At the last minute, though, fortune smiled on the Catholics. When he heard a rumor that Polish Cossacks had invaded Upper Hungary and that the Catholics in Transylvania were preparing to rise up against him, Bethlen Gabor led his army back to Transylvania. This, in turn, compelled Thurn to return to Bohemia.

Polish King Sigismund III Vasa, a Catholic monarch who wanted to rid himself of the troublesome Cossacks at the time of the Bohemian revolt, had arranged with the Austrian Hapsburgs for thousands of Cossacks to join the Imperial army. The troop transfer began in March 1619 and lasted for five months. Although as many as 19,000 were promised, the majority never made it. The reason they never made is not clear. Although some were supposedly intercepted or blocked, it is more likely that many chose to desert. But 3,000 Cossacks did join the Imperial army in 1620.

The Bohemian army received 4,000 reinforcements from the United Provinces and Scotland in the spring of 1620, too. Mansfeld raised fresh mercenaries to serve in his corps. In addition, Bethlen Gabor sent 9,000 Transylvanian cavalry under Jarmusch Bornemissa to assist the Bohemians.

The opposing Catholic and Protestant forces were back at their starting points in the winter of 1619-1620 eyeing each other across the Bohemian-Austrian border. In the spring of 1620, Anhalt led the Bohemian army into Moravia where he won some minor victories. During that same period, John George, the Elector of Saxony, who was a Lutheran, entered an alliance with Emperor Ferdinand whereby the Saxon army would take the field in support of the Catholic cause.

Duke Maximilian fielded 30,000 Catholic League troops in May 1620. He dispatched mercenary commander Johann Tserclaes Tilly with 18,000 troops to Austria, deployed 7,000 along the Bavarian-Upper Palatinate border, and retained 5,000 to garrison Bavarian cities. Born in Brabant in the Spanish Netherlands, Tilly had served as a young soldier in the Spanish army fighting the Dutch. He was later hired by the Austrian Hapsburgs to serve in the Imperial army where he rose to become a field marshal during the Long Turkish War. Duke Maximilian hired him in 1610 to command the Bavarian forces.

Onate worked out an agreement between Ferdinand and Maximillian whereby the Bavarian army would occupy part of western Austria as collateral until Ferdinand repaid Maximilian for the use of his army. After this was arranged, Tilly crushed Protestant unrest in Upper Austria. By the summer of 1620, the Imperial army also had 30,000 troops in the field. Bucquoy commanded a corps at Krems in Lower Austria, Dampierre led a corps at Vienna, and Baltasar Marradas led a corps at Budweis.

The Spanish sent three million ducats to Ferdinand to finance his war machine. In September 1620, Tilly and Maradas joined Bucquoy in Krems, which became the staging area for an invasion of Bohemia. Meanwhile, the Hungarian Estates crowned Bethlen Gabor as their king on August 20 in a ceremony at Pressburg. The Hungarian king had a firm grip on the city with 20,000 troops. Bucquoy sent Dampierre to liberate Pressburg. To achieve this objective, Dampierre had an army composed of Polish Cossacks, Inner Austrians, and Hungarian Catholics. Although Dampierre was slain in action at Pressburg on October 9, his troops succeeded in burning the Danube Bridge. This discouraged Bethlen Gabor from marching north to assist the Bohemians.

The 32,000-strong Catholic army was nominally commanded by Duke Maximilian, but Tilly and Bucquoy made the operational plans and carried them out. As for the 27,500-strong Protestant army, it was nominally led by Anhalt, but the de facto commander was Thurn. In addition to Thurn and Hohenlohe, Schlick had joined the main army from Lusatia. Although Schlick was both competent and experienced, his input was ignored completely by the other two generals. With a major battle looming, the advantage lay with the Catholics whose troops were far more experienced than their Protestant counterparts.

The Protestant commanders remained near Znaim in the mistaken belief that the main Catholic army intended to invade Moravia. But the Catholics had set their sights on Prague. In mid-September, the Saxons seized Bautzen in Upper Lusatia as a preliminary move to invading Silesia if instructed. By November virtually all of Lusatia was under the Saxon thumb. When the Catholic army crossed into Bohemia, Anhalt marched towards Pilse where Mansfeld was situated. For some unknown reason, Mansfeld did not join the main Bohemian army.

Unfortunately for the Catholics, Tilly and Bucquoy began to squabble with the former favoring an aggressive posture and the latter arguing for a conservative approach. Tilly rightly argued that southern Bohemia had been extensively pillaged during two years of continual warfare and could not support the Catholic army. In addition, typhus was spreading through the ranks and taking its toll on the Catholic troops. With Maximillian accompanying the army, Tilly prevailed.

Tilly ordered Baltasar Marradas to take his corps and block Mansfeld while the main Catholic army continued its march toward Prague. Anhalt began falling back to the northeast on the Pilsen-Prague road before the advancing Catholic army. At Rakonic, which was 30 miles from Prague, King Frederick visited the camp to the cheers of the Protestant troops. Anhalt, who was expecting a fight, ordered his troops to entrench on high ground. Beginning on October 30, the armies faced each other at Rakonic for four days. Tilly sent companies of musketeers forward to probe the Protestant army in an effort to gauge its strength. After one sharp skirmish, the victorious Catholics occupied a walled cemetery. Afterward, Bucquoy sent his light cavalry to harass the enemy. The two sides engaged in a desultory artillery duel on the third day. On the fourth day, Tilly marched his troops around Anhalt’s northern flank, compelling his adversary to abandon his strong position. Bucquoy, who was riding ahead with cuirassiers to reconnoiter the road, was wounded.

Fortunately for the Protestants, they won the race to the outskirts of Prague. They filed into position on White Mountain, the last defensive position outside the Bohemian capital. Five miles behind them was the city. When Anhalt ordered them to entrench, they made various excuses, such as the soil was too hard. It was an ominous sign of disobedience on the part of his troops and a clear indication that their morale was waning.

The Protestant army deployed across the low ridge. Its right flank was anchored by a royal residence known as the Star Palace. The residence was surrounded by woods that in turn were enclosed by a long wall. The Protestant left was unanchored, which left it vulnerable to being turned. Moreover, the troops on the Protestant left were on flat ground. To reach the Protestant position, the Catholics would have to cross a shallow stream called the Scharka, which was lined on both sides by marshes.

On the day of battle, November 8, the Catholics fielded 24,800 troops compared to the Protestants’ 23,000 troops; however, the Catholic troops had about 18,000 infantry compared to the Protestants’ 12,000 infantry. Anhalt arrayed his troops in three lines. In the first two lines, he alternated the horse and foot units. The third line consisted almost entirely of the questionable Transylvanian hussars, who were under their second in command, Gaspar Kornis, since Bornemissa had been wounded in a cavalry skirmish. Some of the Transylvanians had been badly mauled in skirmishes with the Imperial cuirassiers and were in no shape for battle.

The Bohemian Royal Foot, which constituted the reserve, formed up in the center of the third line. Thurn commanded the left, Hohenlohe the center, and Schlick the right. Dutch pikemen of the Saxe-Weimar Infantry Regiment held the grounds of the Star Palace on the extreme right flank. In advance of the front line were a half dozen artillery pieces supported by musketeers drawn from Schlick’s infantry regiments. Schlick’s troops were Germans, Moravians, and Silesians. Hohenlohe’s troops were mostly Bohemians and Germans. Thurn’s troops were almost entirely Bohemians.

The Catholic host was divided into two wings. The Imperial troops formed the right wing, which was the traditional place of honor, opposite Thurn and Hohenlohe, and the Catholic League troops formed the left wing opposite Schlick and Hohenlohe. Ordinarily Bucquoy would have commanded the Imperial wing, but he was still incapacitated, so Rudolf von Tiefenbach assumed overall control of the Imperial forces.

The Imperial troops advanced in three lines, whereas the Catholic League forces advanced in two lines. Prince Maximilian of Liechtenstein commanded the first line of the Imperial right wing, and Tiefenbach led the second and third lines of the Imperial right wing. The Imperial ranks in both lines contained Walloon and German cuirassiers and Spanish and German infantry. Several hundred Polish Cossacks reported for duty on the day of the battle.

Tilly commanded both lines of the Catholic League’s left wing. His troops were Germans and Lorrainers. Although many of the Catholic Germans were from Bavaria, some were from Cologne and Wurzburg. The Catholic League had a dozen heavy guns they nicknamed the 12 Apostles. Tilly kept eight and gave Bucquoy four to use during the battle.

A thick fog carpeted the low-lying areas on the morning of the battle. The Catholic commanders welcomed the fog as it concealed the movement of their troops as they crossed the Scharka. Once across the meandering stream, the Catholics began forming up for their attack about a third of a mile from the Protestant position.

While the Catholics were slowly crossing the stream, the Protestant commanders conferred. Schlick was adamant that the Protestants should attack the Catholic army while it was crossing the stream. Thurn agreed with Schlick, but Hohenlohe argued in favor of adhering to the original plan. Anhalt, who lacked experience and was therefore conservative in his tactics, overruled the idea.

The Scharka, which was situated on Tilly’s left flank once the army had completed its crossing, constricted Tilly’s front. It was probably far narrower than he would have preferred and undoubtedly caused a problem for his cavalry.

Each wing of the Catholic army formed five infantry tercios. By the outbreak of the Thirty Years War, the tercio had been the dominant tactical formation for infantry for more than a century. The Dutch and Swedes had developed alternatives to the tercio, and the Protestants were probably inspired by the Dutch method for they had divided their large infantry regiments into two smaller battalions. A tercio was a roughly 3,000-man infantry formation with pikes in the center and muskets concentrated in so-called sleeves on each of its four corners, as well as musketeer skirmishers in front. The musketeers softened up the opposing formation with their shot in preparation for a followup attack by the powerful block of pikes that formed the core of the tercio. If cavalry threatened the musketeers, they could take cover inside the formation or even underneath the bristling pikes. Tilly and his colonels had a wealth of experience in leading and directing tercios in combat.

As for the cavalry, there were a variety of types on the field of White Mountain. Heavy cavalry consisted of heavily armored Polish and Hungarian lancers, as well as heavily armored cuirassiers who carried long swords used primarily for thrusting. Both types of heavy cavalry carried a brace of loaded pistols stored in saddle holsters for use in the caracole, which was a method whereby each rider in a file rode toward the enemy, fired his pistols, and rode to the back of the file to reload and wait his turn to fire again.

Various kinds of medium and light cavalry participated on both sides. The medium cavalry were partially armored arquebusiers, also armed with pistols and swords to cover any contingency, as well as light cavalry, which were primarily eastern horsemen, such as Cossacks or Croats, who carried a lance, carbine, and pistols. These men attacked in a zigzag fashion that allowed them to fire one pistol to the right, the other to the left, and their carbine to the right before wheeling off to reload.

While Bucquoy organized his cavalry into 23 small squadrons, Tilly chose to mass his cavalry in seven large formations. The 12 Apostles fired in unison at 12:15 pmas the signal for a general advance. Shortly afterward, the Catholics began their advance. “The attack finally began between 12 and 1 o’clock, and on both sides there was great zeal and bravery, and the artillery fired against each other with great din and thunder,” wrote German chronicler Johann Philipp Abelinus.

Tilly had previously surveyed the ground over which they would attack, and he instructed Tiefenbach to attack first so that the Catholic troops assaulting the high ground would have sufficient time to climb the slope under fire. Anhalt had sent forward two cavalry regiments to contest the Catholic advance, but they were swept from the field by a spirited attack by Jean de Gaucher’s Walloon regiment of veteran arquebusiers at the head of Bucquoy’s wing. Formed into four squadrons, they overwhelmed the enemy vanguard, which possessed none of the flair showed by the Walloons. Tiefenbach then ordered Colonel Stanislaw Rusinovsky to lead his 800 Cossacks in a sweeping charge around the enemy’s open left flank. They thundered off to harass and unnerve the enemy, doing more harm to the enemy’s psyche with their presence than actual harm with their swords. The Transylvanians made no effort to contest the advance. Anhalt was completely taken aback by the full-scale attack by the Catholics. He had expected Tilly to probe his position as he had done at Rakonic. It was a terrible, unnerving surprise. At the base of the slope, the Protestants heard the Catholic war cry as thousands of troops shouted “Sancta Maria!”

Thurn had divided his Bohemian infantry regiment into two battalions. The first-line battalion numbered 1,320 men in six companies, and the second-line battalion numbered 880 men in four companies. He sent his first line battalion toward Bucquoy’s advancing tercios. Thurn’s musketeers halted to fire a volley at long range, and then they promptly fled from the enemy.

Christian Anhalt the Younger, who led three companies of arquebusiers in the second line near the center of the battlefield, ordered his men to ride forward to fill the breach, a difficult task given that he had only 300 men. They fired into the Imperial tercios as they advanced. At that point, Bucquoy, having decided he could not stand the idea of missing the grand assault, arrived on the field. Supporting Gaucher were waves of well-led, Imperial cuirassiers and arquebusiers who shattered Anhalt the Younger’s German-Bohemian cavalry, capturing their bold commander in the process. None of the Protestant horse came to Anhalt the Younger’s assistance; instead, they all began to quit the field. Seeing the cavalry depart, the remaining infantry of the Protestant left and center fled toward Prague.

The Protestant right, under the command of Schlick, held on about a half hour longer, but that was only because Tilly’s tercio juggernaut had not yet struck them. After putting up a half-hearted fight, the Protestant right fled as well. By 1:30 pm, the entire Protestant force, save the pike troops at the Star Palace, had fled.

What began as a retreat turned into a rout when rumor spread that the Cossacks had cut off their retreat. Some of the Protestant troops were so unnerved that they drowned trying to swim across the Moldau to safety. An attempt to form a rear guard to hold the Charles Bridge and prevent the Catholics from gaining the city even failed.

Maximilian was amazed. In his wildest dreams he had not though the day would be so easily won. The Protestants suffered 2,400 casualties compared to 650 Catholic casualties. King Frederick conferred with Anhalt and Thurn, both of whom told him that there would be no more fighting that day.

In the days that followed, Maximilian granted the Protestant troops amnesty. This brought about the complete disintegration of the main Bohemian army. Although Mansfeld was still in the field, there would be no more resistance. The leaders of the rebellion were only concerned with how to save themselves given that Ferdinand was likely to exact a harsh retribution. Frederick fled first to Silesia and then to Brandenberg.

White Mountain was more of a rout than a hard-fought battle. The Protestant princes of Germany and the anti-Hapsburg powers of Europe had left Frederick and his rebels to fight their battle alone against heavy odds. It was no wonder they failed. The tide of battle would not turn in the Protestants’ favor until the arrival of Swedish King Gustavus Adolphus in Pomerania in 1630.

Join The Conversation

Comments

View All Comments