By Flint Whitlock

His world was literally crashing down in flames around him. Adolf Hitler’s Third Reich, which he had created out of nothing but his own will—an empire that he had once boasted would last for a millennium—was on fire and being torn apart by shot and shell, besieged on all sides. It was an apocalyptic scene straight out of the Wagnerian opera Die Götterdämmerung—The Twilight of the Gods.

The once stately city of Berlin was little more than flaming husks of buildings. Worse, the enemy Hitler hated and feared —the Red Army—was practically at his doorstep.

It was the end of April 1945. As he sat in the dank gloom of the Führerbunker deep beneath the garden of the Chancellery in Berlin, Hitler no doubt reflected on all that had happened to him and to Germany in the past 12 months, almost all of it bad.

Back in April 1944, the British and Americans in Italy were still bottled up at Anzio and along the Gustav Line that ran through Monte Cassino, but his commanders had warned him that the situation would not remain a stalemate for much longer; the German troops no longer had the strength to destroy the enemy there.

On the Eastern Front, defeat followed defeat. Hundreds of thousands of German soldiers lay dead or were in Soviet POW camps where most of them would starve to death. As the German Army in the East became weaker, the Red Army became stronger.

Then, in June, the Western Allies had poured across the English Channel in unstoppable waves and had crashed through the so-called “Atlantic Wall” that Germany had spent years and millions of Reichsmarks building as though it had been made out of cardboard.

In July, some of his own traitorous officers had tried to kill him with a bomb at his East Prussia headquarters.

Then came the disasters, thick and fast in the West: the loss of France, Belgium, Holland, and Luxembourg. Only in Holland in September did Hitler win a brief reprieve.

The winter of 1944-1945 was no better. Operation Wacht am Rhein—the German counteroffensive that the Allies called the Battle of the Bulge—had petered out without achieving its goals; tens of thousands of irreplaceable men (not to mention irreplaceable guns and tanks) had been lost.

The once mighty German Navy was hors d’combat, either holed up in ports or lying at the bottom of the sea. The deadly U-boats no longer dominated the waves.

Food and other supplies for the civilian population were also rapidly running out, and the country’s infrastructure was a shambles.

The British and American air forces continued to decimate German cities and industries from the sky, badly crippling tank and aircraft production. Fuel for the planes and panzers was in such short supply that synthetic fuel manufacturing plants had been built deep inside mountains. In May 1944, the Germans had produced 156,000 tons of aviation fuel; by January 1945, thanks to Allied bombing, it had dropped to 11,000 tons.

Germany’s “wonder weapons” that had once seemed so promising—the V1 and V2 rockets and the jet planes—had failed to achieve that promise. And the development of an atomic bomb was barely beyond the experimental stage.

And, despite the SS’s best efforts, not all of the Jews had been exterminated.

Yet, Hitler and a few of his minions still clung to hope—hope that the Americans and British would come to their senses and realize that their common enemy was not Nazi Germany but Stalin’s Soviet Union. Perhaps, Hitler believed, they could still be persuaded to join forces with Germany and throw back the Slavic hordes before they overran all of civilization.

Hitler’s armies, which had once been within striking distance of Moscow, had seen the tables turned. Wehrmacht forces had been steadily pushed back until their remnants were now fighting at a place called Seelow Heights, 40 miles east of Berlin.

Long rows of Russian cannons sitting hub to hub fired their projectiles into German positions. Soviet tanks, accompanied by infantrymen, sprang from their hiding places and pushed forward, steamrolling over all opposition in their way. The handwriting was on the wall, and it was written in blood.

Studying the situation map during his daily meetings with the few officers who remained in the bunker, Hitler, living in “cloud coo-coo land,” as one officer once put it, demanded that so-and-so general or field marshal move such-and-such division or army from there to here.

His sycophantic entourage had not the courage to explain that so-and-so general or field marshal had been killed or captured or could no longer be reached by radio or courier. Similarly, no one dared mention that such-and-such division or army no longer existed. The officers, knowing the end was near, merely clicked their heels and said, “Jawohl, mein Führer,” and pretended to carry out the hopeless orders.

On April 13 Hitler received word that the Red Army of Marshal Fyodor Tolbukhin had taken Vienna. Countering the bad news that day was a shot of good news: American President Franklin Roosevelt had died. Joseph Goebbels, the Third Reich’s propaganda minister, phoned Hitler, crowing, “Mein Führer, I congratulate you! Roosevelt is dead. It is written in the stars that the second half of April will be the turning point for us.”

The next day, however, Goebbels’ elation dissipated as reports came in from the various fronts showing that nothing had really changed on the battlefield. He confessed to his staff, “Perhaps Fate has again been cruel and made fools of us. Perhaps we counted our chickens before they hatched.”

General Dwight D. Eisenhower had already decided to leave the capture of Berlin to the Russians. For one thing, as he told U.S. Army Chief of Staff General George C. Marshall, the Red Army was already closer to Berlin than either the American or British armies were.

For another, Ike knew that the Germans were likely to defend their capital to the last cartridge and could not see expending hundreds of thousands of American or British lives in taking an objective that had more political than military value.

“I regard it as militarily unsound,” Eisenhower told Marshall. “I am the first to admit that a war is waged in pursuance of political aims, and if the combined chiefs of staff should decide that the Allied effort to take Berlin outweighs purely military considerations in this theater, I would cheerfully readjust my plans and my thinking so as to carry out such an operation.”

Ike was not ordered to readjust his plans or thinking. In the end, it would be the Soviets who would pay a tremendous price for the “honor” of taking Berlin.

Hitler swung between two moods. Part of the time he was delusional, believing that somehow some unforeseen event would tilt the war in Germany’s favor. On other days he was rational and realistic, fully realizing that the war was lost.

To prepare for the latter, on April 15 Hitler wrote out orders that, in the event the enemy severed communication between him and the rest of the command, Admiral Karl Dönitz would take command of the northern forces while Field Marshal Albert Kesselring would take command in the west and south.

It was not the first time Hitler had made a realistic assessment of the situation. Six months earlier, when Operation Wacht am Rhein was crumbling, he had told an aide, “I know the war is lost. The enemy superiority is too great.”

He now dictated a proclamation addressed to the “Soldiers of the German Eastern Front.”

It read in part, “For the last time, our deadly Jewish-Bolshevik enemy has lined up his masses for the attack. He is trying to smash Germany and exterminate our people. To a great degree, you soldiers of the East know yourselves what fate is threatening all German women, girls, and children. While the old men and children will be murdered, women and girls will be degraded to barrack whores. The rest will be marched off to Siberia …

“He who fails to do his duty at this time commits treason against our people. Any regiment or division that abandons its position acts so disgracefully that it should be ashamed before the women and children who are enduring the terror bombing against our cities …

“Above all, be aware of the few treacherous officers and soldiers who, in order to save their own lives, will fight against us…. Whoever orders you to retreat must be immediately arrested and, if necessary, killed on the spot, no matter what his rank may be.

“If, in the coming days and weeks, every soldier does his duty at the Eastern Front, then the last Asian attack will be broken, just as the invasion of our enemies in the West will be broken in spite of everything.

“Berlin will remain German!”

On April 16, the Soviets’ final attack was unleashed on Berlin along the Oder River front and in Silesia. The Red Army had gathered 2.5 million soldiers, 6,200 tanks and assault guns, 41,000 artillery pieces (250 guns for each kilometer of front), and 7,200 aircraft. Facing them was Army Group Vistula, with a paltry 200,000 men, 750 tanks and assault guns, and 1,500 artillery pieces.

Four days later, as the thud of artillery shells exploding in the rubble above the Führerbunker began beating an incessant, mournful rhythm, like the drums accompanying a man being marched to the gallows, Hitler celebrated his 56th birthday by emerging briefly from the Führerbunker to greet in the garden 20 Hitler Youth members who had earned the Iron Cross.

The existing newsreel of him, dressed in a heavy wool greatcoat, patting the shoulders and pinching the cheeks and ears of his youthful admirers, shows a broken, withered man trying to keep up a brave front.

Armin Lehrmann was one of the boy soldiers with whom Hitler had chatted that day. He recalled that Hitler “shook hands with everybody.” But the famous voice was gone. “It was not an orator’s voice. It almost sounded like he had a cold, and his eyes looked watery, and his voice didn’t come across very strong.”

As the Soviets smashed deeper into Germany, a wave of panic and hysteria overcame many of the civilians in their path, especially the women. Rumors and factual accounts of women and girls being gang-raped by drunken Red Army troops drove thousands of Germans to commit suicide. Many took poison, shot or hanged themselves, or threw themselves off cliffs or into rivers. In Berlin alone, in April and May, nearly 4,000 people killed themselves.

One 11-year-old girl who survived nearly being killed by her own mother to prevent her from falling into Russian hands, recalled, “We had no hope left for life, and I myself had the feeling that this was the end of the world, this was the end of my life.” Somehow she survived.

At a meeting with his staff at the Propaganda Ministry, Goebbels voiced Hitler’s complaint that he, the Führer, was surrounded by cowards and traitors, and that the German people were no longer worth fighting for. When someone dared to challenge that assertion, the minister lashed out: “The German people? What can you do with a people whose men are no longer willing to fight when their wives are being raped?

“All the plans of National Socialism, all its dreams and goals, were too great and too noble for this people. The German people are just too cowardly to realize these goals. In the East, they are running away. In the West, they set up hindrances for their own soldiers and welcome the enemy with white flags.” Bitterly, Goebbels spit out, “The German people deserve the destiny that now awaits them.”

But he put on a mask for the sake of national morale. In his final broadcast to the German people, in case any of them were still listening, Goebbels declared, “The Führer is in Berlin and will die fighting with his troops in the capital.”

The Führer may have been in Berlin but he had no intention of dying fighting with his troops on the barricades that now blocked many of the city’s streets. He was hunkered down in his bombproof bunker below the garden of the Reich Chancellery, worrying about what the Russians would do with him if they captured him alive.

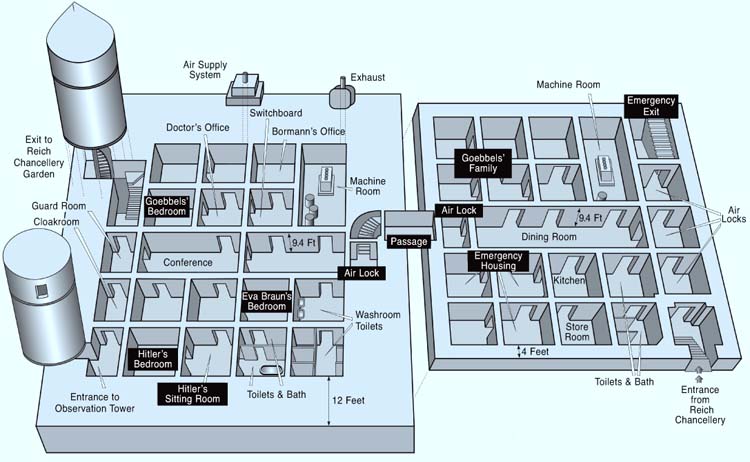

The Germans were highly skilled at building underground facilities of all sorts, and the Führerbunker was no exception, although it was anything but luxurious. It consisted of two levels of rooms. The bunker had been built in two phases, the first in 1936 and the second in 1944. Hitler had moved into the underground chamber in January 1945, making only occasional forays to the outside since then.

The upper level (Vorbunker), beneath 13 feet of concrete, comprised a dozen small rooms (four of which were the kitchen) flanked by a central hallway. At the end of the hallway a spiral staircase wound its way down to Hitler’s quarters.

Here were 18 rooms, also quite small, where Hitler and many of his staff lived and worked (Hitler and his mistress Eva Braun occupied six of the rooms), a far cry from the spacious and elegant offices in the Chancellery.

The passageway on this level doubled as an 18-square-foot conference room unadorned with decoration; a large table held a map of the combat areas. Found on this level, too, were the telephone exchange and a power-generating/ventilation station, along with bathrooms. A battalion of 600-700 SS men of the Leibstandarte Adolf Hitler were billeted nearby and served as guards, orderlies, clerks, servants, and cooks.

Besides Hitler and Eva, other residents of the bunker complex were Hitler’s Machiavellian Deputy Führer Martin Bormann; Dr. Ludwig Stumpfegger, one of Heinrich Himmler’s physicians who was now Hitler’s; Goebbels’ adjutant, Günther Schwägermann, and his undersecretary of state at the Ministry of Propaganda, Werner Naumann; plus Hitler’s adjutant, his two secretaries, and his vegetarian cook.

At his last major conference on April 22, after learning that his orders for a counterattack had been disobeyed, Hitler flew into a tirade, spending hours venting his rage at the world, at the German people, and at the German officers and soldiers who had abandoned him and the Fatherland. Those who witnessed and listened to this venomous outpouring were truly frightened. Many thought the Führer had at last gone completely mad.

On that date, too, the eight-member Goebbels family moved from their apartment on Hermann-Göring-Strasse into quarters within the already overcrowded bunker. The diminutive propaganda minister assured his Führer that he and his family would remain faithful to the end.

After inflicting heavy casualties on the Soviets, the Germans abandoned Seelow Heights and pulled back toward the capital in an orderly fashion. On Monday, April 23, three days after Hitler’s birthday, the Red Army penetrated the outer ring of defenses around Berlin.

Elsewhere around the city, the Germans gave as good as they got; 2,800 Soviet tanks were destroyed and thousands of Red Army soldiers were killed or wounded by the defense that was growing stiffer and more fanatical by the hour.

Events were rapidly coming to a head. April 25 saw U.S. and Soviet forces meet on the Elbe River, and that night Hanna Reitsch, the famed German aviator and test pilot, landed on an avenue near the Brandenburg Gate in beleaguered Berlin, carrying her lover, the newly appointed commander of the Luftwaffe, General Robert Ritter von Greim, to a meeting with Hitler.

With bits of concrete falling from the ceiling with each explosion above, and knowing that the Russians were closing in on the Chancellery, Reitsch pleaded with Magda Goebbels to allow him to fly the children to safety. “My God, Frau Goebbels,” Reitsch said, “the children cannot stay here, even if I have to fly in 20 times to get them out.” Frau Goebbels refused.

On April 26 Magda dashed off a letter to her son from a previous marriage, Harald Quandt, a lieutenant in the Luftwaffe and a prisoner of war being held in Benghazi, Libya. Perhaps the letter would find its way to him.

She wrote: “My beloved son! By now we have been in the Führerbunker for six days already—daddy, your six little siblings and I, for the sake of giving our National Socialistic lives the only possible honorable end…. You shall know that I stayed here against daddy’s will, and that even on last Sunday the Führer wanted to help me to get out. You know your mother—we have the same blood, for me there was no wavering.

“Our glorious idea is ruined and with it everything beautiful and marvelous that I have known in my life. The world that comes after the Führer and National Socialism is no longer worth living in and therefore I took the children with me, for they are too good for the life that would follow, and a merciful God will understand me when I will give them the salvation….”

She gave the letter to Hanna Reitsch and asked her to deliver it if possible.

On the 26th, Tempelhof airport was captured by the Soviets, and most of Berlin’s eastern, northeastern, and southern suburbs and districts had fallen to the enemy. Some of the major Nazi rats had already abandoned the sinking ship of state. Reichsmarschal and Luftwaffe chief Hermann Göring had the temerity to flee Berlin and then send Hitler a telegram declaring that, because he had heard that the Führer planned to commit suicide, he wanted permission to assume leadership of the Third Reich.

Heinrich Himmler, head of the SS and Gestapo, had also departed. He had been holding secret negotiations with Swedish diplomat Count Folke Bernadotte and, in a self-serving attempt to save his own skin, promised to release more than 30,000 prisoners from Nazi concentration camps.

A furious Hitler then condemned both Himmler and Göring for abandoning him. Albert Speer, Minister of Armaments, was in the bunker when Hitler exploded. Speer said, “An outburst of wild fury followed in which feelings of bitterness, helplessness, self-pity, and despair mingled,” with Hitler blaming Göring for being lazy, corrupt, and a drug addict who “let the air force go to pot.”

Then, said Speer, Hitler slumped back into lethargy and resignation: “‘Well, all right, let Göring negotiate the surrender. If the war is lost anyhow, it doesn’t matter who does it.’ That sentence expressed contempt for the German people: Göring was still good enough for the purposes of capitulation.”

Himmler was a different matter. Since the “faithful Heinrich” was out of Berlin and beyond Hitler’s reach, the Führer took out his anger at the SS chief on Hermann Fegelein, Eva Braun’s brother-in-law and Himmler’s representative attached to Hitler’s staff. Fegelein was arrested and executed on April 27.

Speer took his leave from the bunker and spent a few minutes in the Court of Honor in the darkened Chancellery that he had designed and built. Wistfully, he recalled, “Now I was leaving the ruins of my building, and of the most significant years of my life.” He then escaped and flew off to Hamburg to join Dönitz at his headquarters at Plön in Schleswig-Holstein.

On the 28th, Stalin’s troops were within a mile of the Chancellery, which was crumbling under artillery, rockets, and aerial bombing. The next day, although the LVI Panzer Corps, defending the city, was almost out of ammunition, Hitler ordered it to fight to the last man.

The fighting in the streets of Berlin was approaching a climax. Soviet troops had reached the Tiergarten, once a royal hunting preserve, and artillery continued to pound the city, blowing apart what few walls remained standing. Dug into the rubble with panzerfausts and bolt-action rifles, the old men of the Volkssturm and the young boys of the Hitler Youth fought a losing battle against the better equipped Red Army troops.

Considerable postwar focus has been put on the Volkssturm and Hitler Youth as the major defenders of Berlin, but they were only a small part. While the LVI Panzer Corps fought in and around the city, the bulk of responsibility for coming to the rescue of Berlin was placed on the decimated Army Group Vistula’s 9th Army, 21st Army, and Third Panzer Army. What was left of the 12th Army, too, was thrown into the breach at Potsdam. But even these units, badly depleted and demoralized, could not stop the overwhelming numbers and firepower of the Red Army that tightened the noose around the city.

Hanna Reitsch, still in the bunker, was also given letters from some of the other residents, plus instructions intended for Admiral Dönitz at Plön. Initially both Reitsch and von Greim vowed to stay and die with their Führer, but he ordered them to leave. On April 28, they flew out of Berlin, barely avoiding being shot down by the Russians.

The pair was later captured by the Red Army. Von Greim committed suicide on May 24, 1945. Reitsch would learn later that her father, so fearful of what the Soviets might do to his family, had killed his wife, Hanna’s sister Heidi and her three children, and himself on May 3.

April 30 saw elements of the Soviet Third Shock Army break into the Reichstag building and engage in room-to-room combat with SS soldiers. Once all the defenders had been killed or captured, Red Army soldiers raised the blood-red Soviet flag atop the badly scarred building.

As the bunker shook and shuddered under ceaseless barrages, a pale and visibly trembling Hitler sat down with his secretary Traudl Junge and dictated his lengthy and rambling “political testament.” Among other things, he appointed Dönitz the new president of the Third Reich. He then vowed that he would never to leave Berlin, preferring to remain to direct the defense of the city even if it cost him his life.

He said to Junge, “Since there are not enough forces to withstand the enemy attack at this point and our resistance is slowly being weakened by blinded and spineless characters, I wish to join my fate to that which millions of others have taken upon themselves and remain in this city. In addition, I do not wish to fall into the hands of an enemy who, for the amusement of its incited masses, needs a new spectacle directed by the Jews.”

Hitler gave Goebbels and his family permission to leave the bunker, but Goebbels and Magda decided to remain loyal to the bitter, ghoulish end, for they knew that if they were captured alive, theirs would be a most unpleasant fate.

In March, Magda Goebbels had confessed to her former sister-in-law, “We have demanded monstrous things from the German people and treated other nations with pitiless cruelty. For this the victors will exact their full revenge … we can’t let them think we are cowards. Everybody else has the right to live. We haven’t got this right—we have forfeited it. I make myself responsible. I belonged. I believed in Hitler and for long enough in Joseph….”

On April 30, Hitler did something extraordinary. He told Junge, “Since I did not feel that I could accept the responsibility of marriage during the years of struggle, I have decided now, before the end of my earthly career, to take, as my wife, the girl who, after many years of loyal friendship, came of her own free will to this city, already almost besieged, in order to share my fate. At her own request she goes to her death with me as my wife. Death will compensate us for what we were both deprived of by my labors in the service to my people.”

Hitler, of course, was referring to his long-suffering mistress Eva Braun, who had existed in the shadows for so long that hardly any German even knew about the plain blonde cipher who preferred fashion catalogs and movie-star magazines to anything more intellectually stimulating. If it seemed to her that it was a cruel joke as the most powerful man in German history was going to make her “an honest woman” on the brink of their mutual deaths, she said nothing about it. She just smiled her wan smile and enjoyed her brief moment in the rapidly dimming spotlight.

Hitler went on: “My wife and I choose to die in order to escape the shame of overthrow or capitulation. It is our wish that our bodies be burned immediately, here where I have performed the greater part of my daily work during the 12 years I served my people.”

Hitler’s biographer John Toland wrote that perhaps Hitler “feared that [marriage] might diminish his uniqueness as Führer; to most Germans he was almost a Christlike figure. But now all that was over and the bourgeois side of his nature impelled him to reward his faithful mistress with the sanctity of matrimony.”

On the evening of April 30, the couple—with Hitler in his usual uniform and Eva in a black silk taffeta dress, said their wedding vows in front of a small coterie of eight guests; a minor official had been found to officiate. Throughout the bunker, groups of staffers smiled and celebrated. It was the first time in many weeks there had been anything worth smiling about.

The smiles did not last. The artillery continued to drum overhead. It seemed as if the fighting was drawing ever closer to the bunker. Soon the war, and perhaps all of their lives, would be over.

That evening, while Hitler and Eva were relaxing with the other residents of the bunker, the Führer decided to hand out a strange gift to all assembled: cyanide capsules. Someone wondered if they would be effective; after all, they had been supplied by the traitor Himmler. Dr. Stumpfegger suggested one of the capsules be tested on Hitler’s beloved German shepherd Blondi. Strangely, Hitler went along with the idea.

A doctor in the bunker hospital was summoned and ordered to give the poison to the animal; it died within seconds. The group put their capsules into their pockets to be used “when the time was right.”

News was then received that Hitler’s one-time Italian ally, Benito Mussolini, had been captured by partisans, killed, his body badly abused by his furious countrymen and strung up by the heels in a Milan gas station along with his mistress and a handful of other followers.

Hitler shuddered at the thought that the same thing could happen to him. “I will not fall into the hands of the enemy, dead or alive,” he declared. “After I die, my body shall be burned and remain undiscovered forever!”

Adolf Hitler took his own life, and that of his bride Eva, late on April 30. Rochus Misch, a Polish-born SS-Mann who had been a member of Hitler’s bodyguard for five years, recalled that Hitler had locked himself in his room with Eva shortly after their wedding.

“Everyone was waiting for the shot,” Misch said. “We were expecting it…. Then came the shot. Heinz Linge [Hitler’s valet] took me to one side and we went in. I saw Hitler slumped by the table. I didn’t see any blood on his head. I saw Eva with her knees drawn up lying next to him on the sofa….”

Hitler’s chauffeur, Lt. Col. Erich Kempka, had just returned to the bunker with a detail of men who had braved shot and shell to retrieve 170 liters of gasoline. Dr. Stumpfegger and Linge carried the Führer’s body up the stairs and into the garden 10 feet outside the bunker; Martin Bormann followed, carrying Eva Hitler’s limp body. She was placed at her dead husband’s right side.

Russian shells were coming closer, and the men hurried with their tasks. Between bursts Kempka grabbed a jerry can and poured some of the fuel on his beloved master. A nearby burst caused him to retreat to a sheltered place. Once there was a lull, Kempka, Linge, and SS Major Otto Günsche, Hitler’s personal adjutant, emptied can after can of gas on the corpses.

A rag was found, doused in fuel, lit with a match, and then Kempka, practically in tears, tossed it onto the bodies. With a whoosh, a fireball blossomed over Hitler and Eva. For the next three hours, each time the flames diminished, more gasoline was poured on them to keep the pyre going.

Later, with their bodies reduced to ashes and scorched bones, the remains were swept into a piece of canvas, laid into the bottom of a shell hole, and covered with dirt. There they would remain until Soviet troops, rummaging through the debris of the Chancellery a couple of days later, came across them and took them back to Moscow for identification.

Martin Bormann sent Dönitz a telegram informing him that Hitler was dead and that the admiral, in accordance with the Führer’s last wishes, was now president of the Reich.

On the evening of May 1, most of the Hitler entourage was still in the bunker, hearing and feeling the Russian shells bursting above them. The time had come for the final act. Magda Goebbels gathered her six children by Joseph—Helga (12 years old), Hildegard (11), Holdine (eight), Hedwig (seven), Heidrun (four), and son Helmut (nine), and prepared for the end.

She dressed her five daughters in long white nightgowns and then lovingly brushed their hair. Magda told them, “Don’t be afraid. The doctor is going to give you a shot now.”

Then, at about 8:40 pm, at the direction of Magda, the children were given an injection of morphine by Helmut Kunz, an SS dentist. After the war, Kunz testified, “I injected them with morphine—the eldest daughters first, then the son, then the other daughters. It took around ten minutes.

“When the children were off, Magda Goebbels went into the room, the cyanide capsules in her hand. She was in there for several minutes, then stepped out, crying, saying ‘Doctor, I cannot do it. You must.’

“I answered immediately, ‘No, I cannot.’ Then she cried, ‘Well, if you cannot do it, then get Stumpfegger.’”

Dr. Stumpfegger was then summoned. It was he who would carry out the murder of the children. They were not immolated.

Once their children were dead, Magda and Joseph prepared to commit suicide. Goebbels said to Rochus Misch, “Well, Misch, tell Dönitz that we knew how to live. Now we know how to die.”

Goebbels then made a little joke, telling those around them that they were going to walk up to the garden to save everyone from having to carry their bodies up the steep steps. He put on his gloves, and then he and Frau Goebbels, who was near collapse, proceeded arm-in-arm up the stairs to the garden, and to their deaths.

Goebbels made his adjutant, Günther Schwägermann, promise to cremate both his and his wife’s bodies. By some accounts they took cyanide and then were administered a coup de grace from Schwägermann’s pistol. Their bodies were then doused with gasoline and incinerated.

With the Hitlers and the Goebbels now dead, those closest to them at the end chose to make their escape from the doomed city. A few made it—Bormann, Kempka, Schwägermann, Stumpfegger, Günsche, Naumann, Linge, Kunz, Junge, and several others.

When the Russians broke into the Chancellery ruins on May 2, they found Joseph and Magda’s burned corpses, took the remains to Magdeburg, and buried them. In 1970, at the direction of KGB director Yuri Andropov, the remains were exhumed, crushed, and dumped into the Biederitz River near Berlin.

With Hitler gone, Nazi Germany’s end came swiftly. At 2:30 am on May 7, Colonel General Alfred Jodl, commander of the Wehrmacht, arrived at SHAEF headquarters in Reims, France, to sign the official Instrument of Surrender; Eisenhower declined to attend. He sent his deputy, Lt. Gen. Walter Bedell Smith, to act in his behalf. Jodl accepted the Allies’ demands that all resistance cease by 11:01 pm on May 8. Most of the war-weary Axis soldiers gladly laid down their arms, surprised and grateful to find themselves still alive. A few diehards, however, ignored the order and continued to fight.

A few days after Germany capitulated, Sidney Olson, a LIFE magazine correspondent, wrote, “The collapse of the Nazi empire is a fantastic show. Germany is in chaos. It is a country of crushed cities, of pomposities trampled to the ground, of frightened people and also glad people, of horrors beyond imagination …

“There are no cities left in Germany. Aachen, Cologne, Bonn, Koblenz, Wurzburg, Frankfurt, Mainz—all gone in one sweeping reach of destruction whose like has not been seen since the mighty Ghengis Khan came from the East and wiped out whole nations all the way from China to Bulgaria….

“The overall, inescapable fact is that the German people are so solidly, thoroughly indoctrinated with so much of the Nazi ideology that the facts merely bounce off their numbed skulls. It will take years, perhaps generations, to undo the work that Adolf Hitler and his henchmen did.”

The taking of Berlin cost the Soviets dearly. From April 16 to May 2, the Red Army lost more than 361,000 men, including over 81,000 killed or missing. The German defenders lost between 92,000 and 100,000 killed, 220,000 wounded, and nearly a half million men taken prisoner. The battle for Berlin is regarded as the bloodiest battle ever fought.

In 1988, the East German government completed the demolition of the Chancellery site in preparation for the construction of a large apartment complex. Today a small billboard is all that remains to tell visitors of the history of the site.

In his autobiography, Rochus Misch wrote, “Hitler was no brute. He was no monster. He was no superman. I lived with him for five years. We were the closest people who worked with him … we were always there. Hitler was never without us day and night … Hitler was a wonderful boss.” In a 2003 interview, he added, “It was a good time with Hitler. I enjoyed it, and I was proud to work for him.”

History, however, offers a different judgment. Historian Max Domarus has summed up Hitler thus: “Hitler is undoubtedly the most extraordinary figure in German history…. Hitler was power incarnate, a true demon, obsessed with power, the like of whom the world has rarely seen…. Since Napoleon, there had been no tyrant on this scale.”

Albert Speer recalled that on May 1, after he had reached Dönitz’s headquarters at Plön, he was unpacking his bags and found a framed photo of Hitler that his secretary had included. Speer said, “When I stood the photograph up, a fit of weeping overcame me. That was the end of my relationship to Hitler. Only now was the spell broken, the magic extinguished. What remained were images of graveyards, of shattered cities, of millions of mourners, of concentration camps.”

Hitler’s unquenchable thirst for power had brought him and Nazi Germany to unimagined heights, but it also ended in the total destruction of his Third Reich and a cataclysmic reordering of world history.

Still, today—more than seven decades after his death—Adolf Hitler remains the most extraordinary figure in German history.